eBook - ePub

The Dead End Kids of St. Louis

Homeless Boys and the People Who Tried to Save Them

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Joe Garagiola remembers playing baseball with stolen balls and bats while growing up on the Hill. Chuck Berry had run-ins with police before channeling his energy into rock and roll. But not all the boys growing up on the rough streets of St. Louis had loving families or managed to find success. This book reviews a century of history to tell the story of the "lost" boys who struggled to survive on the city's streets as it evolved from a booming late-nineteenth-century industrial center to a troubled mid-twentieth-century metropolis.

To the eyes of impressionable boys without parents to shield them, St. Louis presented an ever-changing spectacle of violence. Small, loosely organized bands from the tenement districts wandered the city looking for trouble, and they often found it. The geology of St. Louis also provided for unique accommodations—sometimes gangs of boys found shelter in the extensive system of interconnected caves underneath the city. Boys could hide in these secret lairs for weeks or even months at a stretch.

Bonnie Stepenoff gives voice to the harrowing experiences of destitute and homeless boys and young men who struggled to grow up, with little or no adult supervision, on streets filled with excitement but also teeming with sharpsters ready to teach these youngsters things they would never learn in school. Well-intentioned efforts of private philanthropists and public officials sometimes went cruelly astray, and sometimes were ineffective, but sometimes had positive effects on young lives.

Stepenoff traces the history of several efforts aimed at assisting the city's homeless boys. She discusses the prison-like St. Louis House of Refuge, where more than 80 percent of the resident children were boys, and Father Dunne's News Boys' Home and Protectorate, which stressed education and training for more than a century after its founding. She charts the growth of Skid Row and details how historical events such as industrialization, economic depression, and wars affected this vulnerable urban population.

Most of these boys grew up and lived decent, unheralded lives, but that doesn't mean that their childhood experiences left them unscathed. Their lives offer a compelling glimpse into old St. Louis while reinforcing the idea that society has an obligation to create cities that will nurture and not endanger the young.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dead End Kids of St. Louis by Bonnie Stepenoff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of MissouriYear

2010Print ISBN

9780826222428, 9780826218889eBook ISBN

9780826272140Chapter One

The City Streets

The first time I ever saw St. Louis I could have bought it for six million dollars, and it was the mistake of my life that I did not do it. It was bitter now to look abroad over this domed and steepled metropolis, this solid expanse of bricks and mortar stretching away on every hand into dim, measure-defying distances, and remember that I had allowed that opportunity to go by.

—MARK TWAIN, Life on the Mississippi

MARK TWAIN CAME TO ST. LOUIS as an ambitious boy, dreaming of becoming a pilot on the Mississippi River. In the 1850s, he prowled the riverfront, boarding the steamboats that were “packed together like sardines” along the levee. He achieved his ambition, but lost his job when the Civil War interfered with river commerce. More than twenty years later, he returned to his old haunts and found that the steamboats had mostly disappeared, but that St. Louis had expanded west of the riverfront to become “a great and prosperous and advancing city.”1

Between the 1840s and the 1870s, St. Louis evolved from a bustling river port to a great industrial center. Railroads and factories moved into the lowlands along the Mississippi River. By 1880, flour, meat, chewing tobacco, malt liquor, paint, brick, cloth bags, and iron topped the list of St. Louis’s products. Coal-powered machinery generated clouds of black smoke that polluted the air. Breweries and other manufacturing plants dumped waste into streets, gutters, and ponds. Freight trains clattered through the bottoms, spewing dust, noise, and prosperity. To escape the dirt and din and enjoy their newfound wealth, many residents moved to the higher ground in the central and western portions of the growing city.2

From a child’s perspective, the story of Chouteau’s Pond dramatizes the changes that took place in the older sections of the city. In the 1760s, French settlers dammed a creek to create power for a gristmill. After Auguste Chouteau purchased the property in 1779, the mill pond became known as Chouteau’s Pond. More than two miles long and about a quarter of a mile wide, the pond was a great attraction for boys and others who enjoyed fishing, boating, and swimming in the summer and skating in the winter. After the cholera epidemic of 1849, city officials drained the pond while creating a sewer system. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Mill Creek Valley, the site of the pond, became the locus of railroad tracks and industrial development, and the city lost a great recreational resource.3

Parks and recreational developments bypassed the eastern part of the city, closest to the riverfront, leaving that heavily populated area without green space in which children could play. In 1868, Henry Shaw donated about two hundred acres of land to create Tower Grove Park, which he named after his home on the grounds of his nearby botanical gardens. In 1872, St. Louis purchased a thousand acres for the magnificent Forest Park, which also encompassed the zoological gardens. Unfortunately for residents of the riverfront area, both these parks were located in the western district of the city. By 1900, the western section of town contained nearly 85 percent (approximately 1,800 acres) of St. Louis’s park land. The central district, with 21 percent of the city’s population, had only 8 percent of the city’s park area, and the eastern district, where nearly half of the city’s 575,000 residents lived, had only 150 acres of park land (less than 7 percent of the total park area).4

Throughout the nineteenth century, immigrants and in-migrants crowded into the older sections of the city. In the 1840s, the city’s population quadrupled, as Germans and Irish people fled social unrest and famine in their homelands. According to the 1850 census, nearly one-third of St. Louis residents were natives of Germany, outnumbering natives of Missouri. The Irish held second place among immigrants, although Germans outnumbered them by two to one. The Civil War slowed immigration in both the city and the nation as a whole, so that in 1870 foreign-born residents accounted for only 36 percent of the city’s population. In the aftermath of the war, which brought an end to racial slavery and spurred in-migration from the rural South, the proportion of African Americans increased from 2 to 7 percent. Many African Americans moved to the drained Mill Creek Valley, where they struggled economically but created an exciting cultural life.5

Street improvements in the growing city increasingly divided the rich from the poor. Low-lying Mill Creek Valley formed a natural topographical division between the north and south sides of town. Railroad tracks, sheds, tanks, and other industrial structures created obstructions for pedestrians, wagons, and carriages in the valley. In the period of most rapid growth, between the 1850s and the 1870s, street crews avoided Mill Creek Valley, making virtually no improvements on the routes connecting the central and northern parts of the city with the south side. Over time, the physical division became a social barrier, as the south side descended into poverty and isolation.6

A variety of ethnic groups crowded into run-down housing in the densely built blocks in the south side near the downtown business district. German immigrants clustered in the vicinity of the Soulard Market, an open-air congeries of food and flower sellers. Throughout the Second Ward, a long, narrow strip of territory running from the levee to the eastern edge of fashionable Lafayette Park, the vast majority of the residents came from Germany, Switzerland, Alsace, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with a small percentage from Ireland. The First Ward, adjacent to and south of the Second Ward, had a nearly identical ethnic composition.7

On a typical street on the south side, small rectangular brick dwellings stood at the front edges of tiny lots. Narrow passageways between the buildings contained flights of wooden stairs leading to second- and third-floor apartments. Most apartments contained two rooms of roughly the same size, with no differentiation between living, eating, and sleeping spaces. Backyards, paved with stone or brick, were cluttered with privies, workshops, toolsheds, and wells. Women washed clothes in sinks on side porches, which also served as summer kitchens and sleeping areas when the heat inside the buildings became unbearable.8

Immigrants of various nationalities tried to make a living by opening businesses on shabby little byways scattered throughout the older sections near the central business district. A Chinese enclave known as Hop Alley occupied an area bounded by Walnut, Market, Seventh, and Ninth streets. Most of the residents were ordinary businessmen and their families, trying to survive by opening laundries, grocery stores, and restaurants. But in the public imagination, fueled by newspaper sensationalism, this was a world of opium, or “hop,” sellers, drug-induced dreams, incense, and smoky rooms. Young men went there at midnight to buy hop and carry it away or lie in rattan bunks and smoke it in pipes.9

A gruesome murder took place in Hop Alley in 1883. The body of a Cantonese man named Lou Johnson was found in the alley, horribly slashed. His head was later found in a basket of rice. Police blamed the killing on the so-called Highbinders, which were secret societies of Chinese men who allegedly committed many murders. Consequently, the authorities arrested and prosecuted six Chinese suspects, but without evidence or witnesses, no conviction was possible.10

As a bizarre sequel to this event, in April 1899, two small boys playing marbles discovered the body of a Chinese man under a large gasoline tank near the sidewalk in front of the Waters-Pierce Oil Company on Gratiot between Twelfth and Thirteenth streets. The boys, Charles McNorman and John Dutton, lived nearby. One of them flipped a marble too hard, and it rolled under the tank. In an effort to find it, he stumbled upon the corpse. The boys ran and told a passerby, who notified the police.11

When the city undertaker’s men arrived on the scene, they found the body on its back, with the neck resting on a brick, and the hands clasped across the chest. Blood had congealed on the man’s face and in his hair. Even for the hardened officials, this was a sickening sight. Police identified the murdered man as Jeu Chow and questioned the residents of Hop Alley. The investigation revealed that he had lived in a house at the rear of 719 Walnut Street, the same house where Lou Johnson had been killed.12

As the downtown area became more dangerous, residents moved into deteriorating neighborhoods on the near north side. African Americans occupied dwellings on Lucas and Morgan streets west of Twelfth and on Wash Street east of Twelfth. People from Ireland, Germany, Austria, Russia, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Greece, and Italy migrated into the area, mingling in the blocks between Seventh and Eleventh streets. Italians found housing between Seventh and Ninth streets, from Lucas to O’Fallon Street. Polish immigrants concentrated along O’Fallon Street and Cass Avenue.13

Jewish immigrants settled on Morgan, Carr, and Biddle streets in this north-side area. The popular Biddle Street Market was a hub of commerce. Merchants sold Jewish foods, literature, religious artifacts, and newspapers from storefronts along Biddle Street, O’Fallon Street, Carr Street, and Franklin Avenue. Non-Jewish residents shared in the local culture and gradually adopted a variety of the Yiddish expressions used in the area, which was sometimes called Little Jerusalem or the Ghetto.14

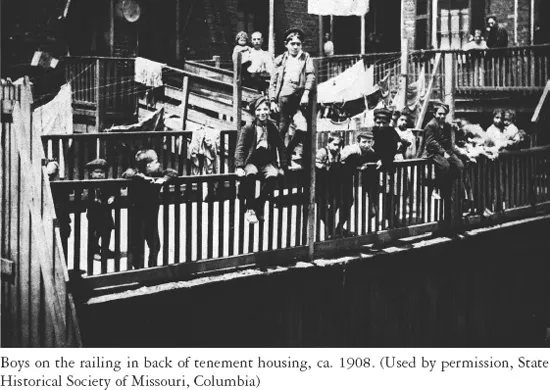

Residents of these north-side neighborhoods typically occupied apartments in two- or three-story brick or frame buildings that had two fronts, one facing the street and one facing an alley. Living conditions were similar to those on the south side. Each apartment building filled the entire width of the lot, leaving room only for a narrow passageway for access to the backyard. Yards were crowded with sheds, privies, stables, ashes, garbage, and manure. Rats infested piles of discarded mattresses, bed springs, and food waste. In most cases, six or more families shared the same yard, and no one took responsibility for keeping it clean. Children played in these yards, or else they went out into the alleys and streets.15

Families with children lived alongside vagrants and prostitutes. Residents tried to make their neighborhoods livable by growing flowers in tin cans on window ledges and doorsteps. Gossiping women congregated in front of grocers and butcher shops. Housewives went out to buy a single egg, three cents’ worth of sugar, or enough meat for a single meal, and stopped and visited on their way to and from the store. Families carried tables out into the alleys and invited friends to eat, play cards, and relax. Peddlers sold candy and cakes from pushcarts. Old men philosophized in coffeehouses. Footloose boys and young men could find all sorts of entertainment on Franklin Avenue. Prostitutes worked in certain constantly changing areas of the district. Saloons served as banks and post offices, cashing paychecks and providing mailing addresses for people who had no permanent lodging. Tramps found shelter in basements and attics, and the shifting, anonymous population drifted into crime.16

Most notorious of all the enclaves on the near north side was the Irish American neighborhood known as “Kerry Patch,” which was peopled by immigrants from Ireland’s County Kerry. The boundaries of the Patch changed constantly as people moved in and out of flimsy dwellings on the northern edge of the city’s central corridor. Most of the residents of Kerry Patch were squatters, working men and their families who built their own shelters on land they did not own. Many of the houses were wooden structures with rags stuffed into broken windows. Within the Patch was a central common, or green, which residents used for gardening and games. The people shared the Catholic faith and participated in a variety of sports and pastimes, including cockfights, dogfights, and boxing matches. They defended their territory against trespassers, including policemen and people of other races and ethnic origins.17

The life histories of William Marion Reedy and his boyhood friends, Johnnie Cunningham and Jack Shea, reveal the dangers for boys growing up in Kerry Patch. Reedy’s father was an Irish-born policeman who walked the beat and raised his family in the “Bloody Third District,” which included Kerry Patch. His first son, William, was born in 1862, while Union troops occupied St. Louis. During William’s childhood, the people of the Patch kept goats and raised vegetables in a common garden. William’s best friend, Johnnie Cunningham, delivered milk from his mother’s cows. Johnnie’s life had a dark side. He robbed people in the streets at night and took his friend William to hideouts in haylofts, where they eluded the police. They pretended they were pirates, and William viewed their activities as boyhood fantasies and adventures. Their mutual friend Jack also played reckless games. Johnnie and Jack did jail time together after William became a reporter. Following a jailbreak, Jack shot and killed a police officer.18

William Reedy graduated from St. Louis University, pursued a career in journalism, and became the editor of a successful magazine called the St. Louis Mirror. His friend Johnnie Cunningham managed to avoid imprisonment, but died in a train wreck. Jack Shea spent many years in the penitentiary, while Reedy prospered. As a successful middle-aged man, looking back on his life, Reedy recalled that he and Cunningham and Shea were very much alike. As boys, they were “much of a piece mentally.” All three were reckless and adventurous. There was no rational explanation for his good fortune and their terrible fates. The only difference between them was that Reedy had parents who kept track of him and punished him when he got out of line.19

Many parents in the poorer sections of the city failed, or were unable, to protect their children. Alcoholism, illness, despair, and death produced what some observers described as hordes of neglected and undisciplined young people, who darted in and out of the crowds on the levee, played games of dice in alleyways, begged, stole, picked pockets, and otherwise harassed honest citizens. J. A. Dacus and James W. Buel, who observed and wrote about the situation in the 1870s, were at a loss to explain how these rootless children eked out a living. Ragged urchins who appeared on the streets in the daytime as newsboys, messengers, beggars, shills, and shoe-shine boys vanished in the winter and at night into vacant buildings, cellars, and caves.20

To the eyes of impressionable boys, without parents to shield them, the city presented an ever-changing spectacle of violence. In the 1850s, although the population of free blacks was growing, St. Louis was still a slave city. Slave auctions occurred frequently on the courthouse steps. Slave-catchers pursued runaways. Newspaper advertisements threatened terrible punishment, even mutilation, for those who were caught. A public whipping post made it clear to everyone that the root of the slave system was brutal coercion.21

When the Civil War began in 1861, pro-slavery militias drilled in a forest at the western edge of the city. On May 10, about six thousand Union soldiers marched on this encampment and demanded unconditional surrender. Outnumbered and outgunned, the secessionists at “Camp Jackson” capitulated. As General Nathaniel Lyon, leader of the Union forces, gathered up prisoners, thousands of local citizens converged on the site. Most of them came to watch, but some came armed with rocks, sticks, brickbats, and guns. Someone opened fire; soldiers and ci...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One - The City Streets

- Chapter Two - Orphans and Orphanages

- Chapter Three - Drifters in the City Streets

- Chapter Four - Games, Gangs, Hideouts, and Caves

- Chapter Five - Juvenile Delinquents and the House of Refuge

- Chapter Six - Child Savers and St. Louis Newsboys

- Chapter Seven - City on the Skids

- Chapter Eight - Young Men and Criminal Gangs

- Chapter Nine - A New Deal for Homeless Youth

- Chapter Ten - Youth and the Changing City Streets

- Conclusion

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index