![]()

CHAPTER ONE

‘[M]UCH FREQUENTED DURING THE BATHING SEASON’

BARRY ISLAND AND WELSH COASTAL TOURISM, c.1790–c.1860

PRECONDITIONS FOR THE RISE OF COASTAL TOURISM IN WALES

TOURISM TO WALES only began in earnest in the final third of the eighteenth century. Before the 1770s, the principality was rarely visited by outsiders. It was widely seen as a primitive and uncivilized corner of the land – an inaccessible place of ‘monstrous’ mountains and uninteresting, uncultured inhabitants.1 Henry Wyndham, an early tourist, remarked that he had gone six weeks without encountering a single English tourist during his peregrinations in Wales in the summer of 1774. He thought that the ‘general prejudice’ against all things Cambrian accounted for the absence of his fellow countrymen. As he put it, genteel metropolitan types took it for granted that ‘Welsh roads are impracticable, the inns intolerable, and the people insolent and brutish.’2

Given such beliefs, it is remarkable that within a few years Wales had become fashionable. The Romantics did much to bring about this transformation in perception. Almost overnight, the very characteristics that had made the land west of Offa’s Dyke deeply unattractive to visitors were now the very features that turned it into a tourist hotspot. Romantics were fascinated by Wales’s supposed primitiveness. Their newfound interest in the grandeur of nature meant that the principality’s mountainous regions went from being barren spaces to repositories of the sublime. Landscape painters imbued with the spirit of Romanticism had plenty to keep them interested, whether they were looking for dramatic cliff faces or a surfeit of waterfalls.3 Likewise, poets found much in the Welsh landscape to stir their Romantic imaginations. Meanwhile, antiquarians discovered Wales to be place with a rich and varied history.

One consequence of this profound reconceptualization was that Wales, like other ‘remote’ and ‘untamed’ areas of Britain (including the Scottish Highlands and the English Lake District), suddenly found itself on the itineraries of many tourists.4 A ‘nascent tourist industry’ developed to support travellers on their ‘Celtic Tour’.5 Hotels sprang up at key locations and a veritable flood of tour guides appeared: between 1770 and 1815, at least eighty titles dedicated to Wales were published.6 As Hywel M. Davies has put it, ‘Accounts of Wales were so numerous during the last two decades of the eighteenth century that “Welsh Tours” constituted a literary type.’7 Tourists’ interest in the principality was only strengthened by the wars with France (which made Continental tourism impracticable) and the fact that new turnpike roads had made travelling a more comfortable experience (in parts of Wales at least).

There was another factor that brought tourists to the principality in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century: a newfound interest in the beach. This development, too, was based on a rethinking of what had once been an accepted truth. In the medieval period, Christendom had been gripped by something of a ‘beach phobia’. It is easy to see why this should have been the case. The Bible, the key source of wisdom for medieval people, depicted the sea as a threatening space of mystery and destruction. In Genesis, the ocean was portrayed as part of the terrifying ‘abyss’ that had preceded creation. Then there was the story of the Great Flood in which the ever-rising waters came close to wiping out life. And whilst the sea could bring peaceful traders, it could also be the means by which hostile forces – such as Vikings – arrived. Hardly a wonder that the beach became, in the minds of many, a ‘sacred threshold’, a place that should ‘only be approached with the greatest trepidation’.8

Nevertheless, a very different understanding of the sea emerged. As the eighteenth century unfolded, so the notion that the beach might in fact be a place of healing gained credence. Medical authorities began celebrating seawater’s near-miraculous curative powers.9 One of the most enthusiastic supporters of hydrotherapy was Dr Richard Russell. His Dissertation on the Use of Seawater in the Diseases of the Glands (published in Latin in 1750 and in English two years later) summed up the new orthodoxy. In Russell’s view the sea was not an instrument of God’s wrath; it was a divine gift that provided mortals with a ‘common Defence against the Corruption and Putrefaction of Bodies’.10 The list of ailments that Russell asserted could be treated with seawater was certainly impressive. It included tumefaction of the glands of the knees, ‘cutaneous Eruptions’, leprosy (in both its ‘moist’ and ‘dry’ forms), gonorrhoea, herpes in the face, obstructions of the rectum, cholic, hardened glands in the neck, ‘hectic fever’ and swelling of the upper lips and nostrils. Once established, the proposition that seawater and, soon enough, sea air, were powerful remedies went on to enjoy a long life. Throughout the nineteenth century, medics issued advice on how best to get the health benefits of a visit to the beach.11

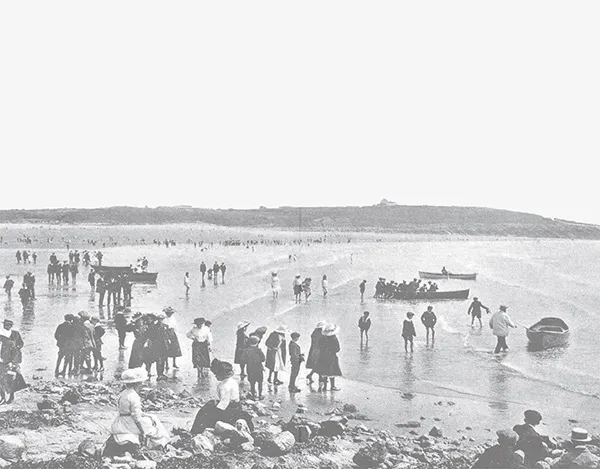

We should note that bathing was not just an elite activity. Labourers had their own ideas about benefits of sea immersion and did not need Dr Russell to be encouraged into the water. We know precious little about such popular bathing habits but there is enough evidence from around the coasts of Britain for us to be certain that members of the working classes were bathing. A travel guide to Wales penned in 1805 contained one such description of a Welsh ‘aquatic orgy’. The author reported that the ‘natives of both sexes among the mountains on the sea-coast of Cardiganshire, and probably in other places’, were ‘much addicted to sea-bathing, during the light summer nights’. On Saturday evenings, the participants left their villages in the hills and headed for the beach, noisily blowing horns as they went. Once at the water’s edge, they stripped and took ‘a promiscuous plunge without any ceremony’. They returned home at daybreak, just as noisily as they had left.12

Nevertheless, it was the social elite that had the means to stay at the seaside for extended periods. As they did so, specialist seaside resorts began to emerge. Early examples were the Yorkshire resorts of Whitby and Scarborough in the 1710s and 1730s respectively. In the second half of the eighteenth century, resorts within reach of London, such as Brighton, Worthing, Southend and Weymouth, all flourished.13 By the mid-nineteenth century, the sea-bathing ‘mania’ was contributing to the urban economies of coastal towns all around the coast of the United Kingdom, from the south-west of England to the north-east of Scotland.14

WALES’S LARGER SPECIALIST WATERING-PLACES

The coast of Wales was fully implicated in the rise of sea-bathing as a cultural practice. Yet we would be forgiven for drawing the opposite conclusion if we only concentrated our attention on the towns that specialized in seaside tourism. After a century of development, Wales had a mere handful of developed resorts: Tenby, Aberystwyth, Llandudno and Rhyl were the largest.15 It will be argued here that we should not see these ‘bigger’ resorts (they were still small by English standards) as being representative of the Welsh experience. However, for the moment, it is important that we note their presence as significant centres of coastal tourism in the principality. In all four cases, tourism had clearly invigorated their local economies and led to some significant urban growth.

In south-west Wales, Tenby had long been declining as a port and a centre of fishing. Its faltering economy was only able to support a population of around 850 at the start of the nineteenth century. However, the arrival of bathers from the 1780s soon gave the little town a new lease of life.16 It was already being described as a ‘Bathing place of very fashionable resort’ by the late 1790s.17 It was widely regarded as the leading Welsh seaside resort in the Georgian period. In the early 1800s, a bath-house and hotels had been built. By the 1820s, with its circulating library, theatre, public reading room stuffed with London newspapers and special seats installed in the parish church just for visitors, Tenby was a town that quickly bore the imprint of its willingness to appeal to the tourist market.18 As the Revd John Evans noted in 1803, its ‘aquatic celebrity’ had led to ‘considerable improvement’ and the building of ‘many modern houses’.19 And its success further boosted its fortunes: by 1851, its population had risen to almost 3,000. This was a substantial enough increase to place it thirty-sixth in John K. Walton’s table of the fifty largest resorts in England and Wales.20

Aberystwyth, on the coast of mid Wales, had a similar experience. Home to about 1,700 inhabitants in 1801, it was an unprepossessing place: according to one early visitor, it had a ‘gloomy appearance’. Nevertheless, its ‘romantic shore’ was attractive enough to draw ‘crowds of company’ to it for the purposes of therapeutic sea-bathing. The bathers came in large enough numbers to lead to the construction of new houses to accommodate them (nineteen were built over the winter of 1823–4 providing eighty more beds for visitors).21 And other tourist-inspired improvements followed, including a scheme to build a ‘new and elegant’ theatre.22 Work on a promenade began in 1819 and assembly rooms were opened in 1820. By 1831, Aberystwyth was playing host to some 1,500 staying visitors every season.23 By 1851, its population had reached over 5,100 making it the twenty-first largest seaside resort in England and Wales by population.24

In north Wales, the fortunes of Rhyl and Llandudno were also materially improved by seaside tourism. Again, both settlements were small. In 1851, Rhyl only had 1,500 inhabitants, Llandudno just 1,100. But, in both cases, the arrival of sea-bathing visitors soon triggered investment in tourist infrastructure. By the early 1830s, Rhyl possessed a ‘commodious’ hotel, a bathing house offering warm seawater and vapour baths and piers specially built to accommodate the steam packets that were operating out of Liverpool.25 By the late 1840s, Rhyl’s popularity with the inhabitants of Liverpool and Manchester meant that visitors were obliged to book their lodgings ‘long before they are wanted’.26 By the mid-point of the century, Llandudno had a number of hotels, a reading room and a Turkish bath and was set fair to develop into a fashionable resort. By 1911, its population of 10,469 made it the largest Welsh resort, and the thirty-ninth largest in England and Wales. Rhyl, with its 9,000 inhabitants, was not far behind.27

The four largest Welsh seaside resorts were relatively small when compared with English seaside towns. When Nigel Yates observed that Wales had made only a disappointing contribution to the development of the British seaside resort, he certainly had a point.28 If we are looking for examples of coastal tourism’s potential to transform urban economies and bring about explosive urban growth, we will not find much to interest us along the principality’s coastline. But the size of a seaside town’s resident population is only one indicator of tourism’s significance. We are in danger of missing an important element of the story of Welsh seaside tourism if we are only on the lookout for equivalents of Brighton and Bournemouth. For besides those few Welsh towns that edged their way into the lower echelons of the league table of the top-fifty largest resorts, there were many more that played their part in the tourist boom of the nineteenth century. Tourism became woven into their economies, even if it did not always lead to dramatic change. There is a striking diversity to the Welsh seaside experience that can be missed entirely if we take too restrictive a view of what constitutes a ‘proper’ seaside resort.29 And, just as importantly, we are in danger of missing a very particular type of tourist: the visitor who shunned the big crowds, who avoided the urbane sophistication of the more fashionable, sector-leading watering places, and who wanted, instead, a more relaxed seaside experience. The bathing villages of Wales catered for just such a tourist.30

‘[L]ARGELY RESORTED TO BY THOSE WHO . . .

SEEK A QUIET SPOT’: WALES’S SMALLER RESORTS

The society-loving seaside visitor is a stock figure in our histories. This is the tourist who, when not bathing, frequented the bustling assembly rooms, the coffee houses, the theatres and concert halls that had been built specially to keep them amused. When they were not looking at the sublime seascape, they were ‘ogling each other’ on the promenades – those purpose-built ‘spaces of intensive display and observation’.31 But such a seaside sojourn was not to everyone’s taste. Throughout the century, there were plenty of tourists who wanted to forgo the disadvantages of holidaying in an overly busy, fashionable watering place. When, in 1790s, Henry Skrine visited Caernarfon, a coastal town in north Wales with a population of approximately 3,500, he was struck by how ‘several English families’ preferred ‘to make it their summer residence for the purpose of avoiding the crowded inconvenience of the more polished, but less simple, public places in the south of England’. There were enough of such well-to-do visitors from England to have a material effect on Caernarfon...