1

SOVEREIGNTY IN THE SKIES

An Anthropology of Everyday Aeropolitics

Rebecca Bryant

In October 2017, the European Aviation Safety Agency announced an increased risk of flight collision over the Mediterranean island of Cyprus (Cyprus Mail 2017a). This island of only one million inhabitants has three major international airports serving Europe and the Middle East. On any given day, the main Larnaca Airport serves around fifteen thousand passengers, numbers obviously fluctuating depending on the season. In high seasons, many of those flights come from Russia, even though the flight path from Russian cities is hardly a direct one, taking passengers on a detour around Turkey. Because the Republic of Turkey does not recognize the government of the Republic of Cyprus (RoC), its ports are closed to vessels carrying the RoC flag, and its airspace and waters are also off limit to them. Instead, Turkey recognizes the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), the breakaway state in the island’s north that has been condemned by the United Nations and whose own airport, Ercan, is considered by the RoC to be an illegal port of entry to the island.

Only two days after a local newspaper reported this story, and international media picked it up, the same newspaper related that in the previous year, Cyprus had experienced the third largest increase in air traffic in Europe (Cyprus Mail 2017b). Of course, the airports being reported on were Larnaca and Paphos, in the internationally recognized southern part of the island. And here, indeed, was the traffic problem, because despite its international isolation, Ercan Airport had experienced a significant increase in traffic over the past decade and was now landing almost twenty thousand planes per year on its one landing strip.1 The head of the Mediterranean Flight Safety Foundation—which, despite its name, is a Greek Cypriot institution—gave the newspaper three reasons for the increased risk:

The main one is that Ankara doesn’t recognise the Cyprus government. The second is that the illegal air control at Ercan airport [in the north] is confusing pilots by giving them instructions which are conflicting with the one of the official air traffic control. Also, the Turkish air force gives no notification of its flights putting people in danger. (ibid.)

According to the head of this south Cyprus-based safety foundation, the main problem is Ercan airport’s illegality, which puts it outside the range of the “official” air traffic control.

This chapter uses aerial sovereignty as a lens onto the “black holes” in international politics created by unrecognized states. Those black holes are ones of information, but also ones of geopolitics and, as we will see, aeropolitics (Abeyratne 2009). My interest in this chapter is not only in viewing the skies as another space to contest sovereignty, though that is certainly important here. It may be the case that de facto or unrecognized states give us a new lens to think about the governance of the air, and more particularly about what the study of flight, aircraft, and disputes over the air above a territory may tell us about everyday geopolitics. However, I believe that the anthropological potential of the aeropolitical extends beyond the aerial space above a territory.

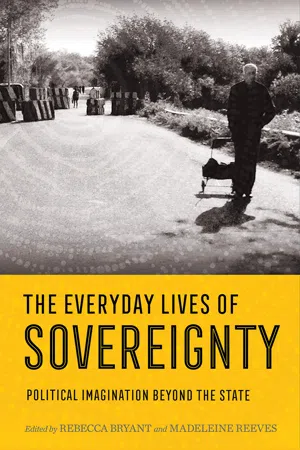

FIGURE 1. Map showing Cyprus’s three airports.

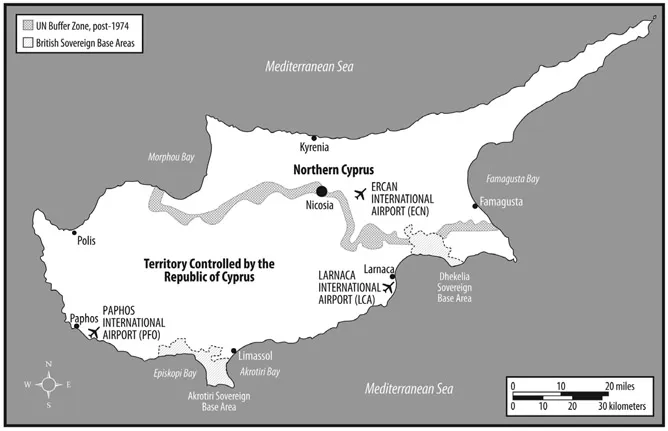

FIGURE 2. Map showing some (though not all) of the destinations from Larnaca Airport.

We know, for instance, that national airlines, or “flag carriers,” represent forms of banal nationalism, reifying the nation through their branding and becoming containers of the homeland in the skies (Raguraman 1997). Flight attendant uniforms, food service, language used, and in-flight magazines are all intended to reify national airlines as aerial ambassadors of the nation-state (Markessinis n.d.; Yano 2011). One commentator growing up in Ghana remarked, on the passing of his own national airline, “To me, a national airline was just another way a country defined itself, along with its flag, national anthem, and currency. Ghana Airways . . . was a perfect example, with the red, gold and green colors of its national flag painted on every plane. They looked proud and elegant, a perfect symbol of statehood” (Lawrence 2012). Moreover, the collapse of more than two hundred national carriers over the past decades has been resisted by states (CAPA 2011), while even British Airway’s removal of the Union Jack from its tailfins in the late 1990s produced protests that forced it to put it back (Dinnie 2008, 89). What, then, can the emotional attachment to national airlines, and the senses of helplessness in the face of globalization produced by their collapse, tell us about sovereignty and sovereign agency?

In recent years, anthropologists have focused increasingly on the nonspaces (Auge 1995) that so many of us frequent on a regular basis: the liminal spaces of airports (Hylland Eriksen and Doving 1992), with their attendant border and customs regimes (Chalfin 2006, 2008), security controls (Maguire 2014; Moreland 2013), and biometric surveillance (Amoore 2006; Maguire 2009). Interestingly, like studies of land border crossings (e.g., Donnan and Wilson 2010), railways (Bear 2007), and roads (Dalakoglou 2017; Harvey 2005; Harvey and Knox 2012), the social science focus has been primarily on the sedentary space rather than on the vehicle that traverses or moves from or through it (e.g., Hiller 2010; Lloyd 2003).2 An exception is the ethnographic interest in cars that has explored emotional attachment, affect, and senses of freedom produced by them (e.g., Lutz and Fernandez 2010; Miller 2001). Trains, ships, and airplanes, however, become the space in which other activities are observed—smuggling (e.g., Nordstrom 2007), human trafficking (e.g., Andersson 2014), and tourism (e.g., Dowling and Weeden 2017), for instance. They most often become spaces for controlling mobility (e.g., Peteet 2017; Pickering and Weber 2006) and its dangers (e.g., Budd, Bell, and Brown 2009).

This chapter instead views these moving containers as complexes of meaning that not only link places but also link state, sovereignty, and peoples. National airlines are an infrastructure of mobility, and one of the first in which new states invest. This chapter further develops a recent literature on infrastructures that points to their totemic role in building collectivities. Infrastructures are, after all, “collectively held” (Rodgers and O’Neill 2012, 406) and “hence can become the metonymic sites for wider social discussions of participation and responsibility—that is, can become meaningful for the very definition of a collective” (Coleman 2014, 460). Larkin, for instance, examines how the introduction of media—cinema, radio, television—produced social transformation in colonial and postcolonial Africa, describing these forms of infrastructure as a “totality of both technical and cultural systems that create institutionalized structures whereby goods of all sorts circulate, connecting and binding people into collectivities” (Larkin 2008, 6). Coleman, studying electricity networks in India and Scotland, moves away in his analysis from the strictly materialistic focus of Actor Network Theory to look instead at infrastructures’ “very collective crafting in the imagination as emblematic of the state and the political community itself” (2014, 461). Recuperating the political potential of Durkheim’s totemism, an idea long out of fashion in anthropology, Coleman shows how the emblem or totem is “the material site where real, but invisible, collective forces gather and are made accessible as representations” (465).

This discussion seems particularly pertinent to a national airline, which I argue here is one of the key sites for totemically representing not simply the collectivity, but the collectivity’s manifestation in stateness. Painter (2006), for instance, argues that the “state effect” (Mitchell 1991) manifests itself in the mundane: through regulating our parking, through determining school and shop hours, and so on. And certainly, as I discuss below, national airlines historically have represented the power and technological prowess of the state. But this is not all. Airplanes are also containers that become small pieces of the homeland outside the homeland itself. It is this combination of containment and connectivity, I will argue, that is the key to understanding airplanes’ totemic power.

I outline below why national airlines are an important site for materializing the state as something that belongs to us, and hence a potential source of sovereign agency. I call that sense of belongingness of the state the “sovereignty effect,” a term I use to refer to the ways in which an abstract externality—“the state”—may come to appear as a vehicle for our agency. It is through this totemic power of national airlines, combining both intimacy and potency, both containment and connectivity, that the state—an externality—appears as ours.

This chapter uses the rise and fall of one national airline, and the privatization of both the airline and its unrecognized home airport, as a vehicle for exploring both the totemic power of infrastructures and the potential of aeropolitics for anthropology. I argue here that like the recent appropriation of geopolitics for the study of political affect and agency (Jansen 2009, Thrift 2000), aeropolitics offers a lens onto the everyday practices that produce stateness, the effect of sovereignty, and a sense of sovereign agency. Investigating the national airline of an unrecognized state also, I show, gives us a lens onto the role played by national airlines in producing belief in the state—or calling it into question in an era of privatization and globalization. As we will see, the de facto state of the skies is one that tells us much about how we imagine and construct sovereignty today.

Everyday Aeropolitics

On one of the main thoroughfares of north Nicosia, a bland modern building with a fading sign stands empty. The building at one time housed Turkish Cypriots’ primary representative of their state in the outside world, the Cyprus Turkish Airlines, or CTA (in Turkish, Kibris Türk Hava Yollari, or KTHY). I still recall the packaged sandwiches with the faint taste of plastic wrapper that they would serve on the short flight to Istanbul, where they would take on other passengers before flying to destinations in Europe, especially the United Kingdom. Like all flights entering or leaving north Cyprus, planes would touch down at various points in Turkey so that aviation authorities could maintain the pretense of allowing no direct flights to the island’s north. The touchdown usually occurred in Istanbul, though Izmir and Antalya were also spots for loading and unloading other passengers.

I first arrived in the island in the early 1990s, a period of isolation for the unrecognized TRNC, which experienced trade and other embargoes. At the time, apart from one struggling low-cost carrier, Istanbul Air, CTA was the only airline flying to Ercan. For this reason, the 1990s were the height of CTA’s activity, also because at the time the border dividing the island was still closed, making the only routes for exit from the north either ferries to southern Turkey or Ercan Airport. In 2003, as a result of a Europeanization process in the island’s south, and subsequent protests in the north, Turkish Cypriot leaders would decide to open the checkpoints. This opening suddenly produced a new social, economic, and political environment in the island, including the opportunity for Turkish Cypriots to fly on direct flights from the Larnaca and Paphos airports.3

In the 1990s, however, when CTA more or less monopolized the market, north Cyprus remained a rather difficult destination to get to, one that for tourists was off the beaten track. It was a period when tourist brochures still sold the island’s north as an “untouched paradise,” and the north’s isolation was palpable in the lack of consumer goods, curtailment of trade, and a sui generis administration where kinship and friendship networks held sway (e.g., Bryant and Hatay 2020; Sonan 2014). The latter also gave to the enclosed space of the island’s north a sense of intimacy.

That intimacy, moreover, was intensely experienced on Turkish Cypriots’ one airline. Flying from those European destinations to the island, I was always struck by the way the atmosphere changed when we took off from Turkey and were on our way to Cyprus. People who had sat patiently for the four-hour journey from London would suddenly be in the aisles, chatting loudly with other passengers. They would joke with the stewardesses, all of whom were Turkish Cypriot. And some people with influence would smoke in the back of the plane, even after smoking had been banned from flights. In the last stretch of the journey, the flight took on the atmosphere of a village bus taking you home.

Indeed, there were many indications that Turkish Cypriots took great pride in seeing this as “their” airline, both an extension of their state as public property, and something that, being public property, was also “their own.” Indeed, it being “our own” was the response that we received more than any other when a coauthor and I put the question of what they missed most about the by-then defunct airline in a 2016 Facebook survey, discussed more below. Quite a few respondents simply said, “It being ours,” while others expressed it as, “It being an institution that belonged to us,” or “Despite all of its negative aspects, it still being ours.”

FIGURE 3. Cyprus Turkish Airlines plane taking off from Ercan Airport. Courtesy of Flickr user Pertti Sipilä.

CTA had been born at the same time as Turkish Cypriots’ first attempt at statehood, the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus (TFSC). The Turkish Cypriot Legislative Assembly declared the TFSC in February 1975, only a few months after Turkish troops stormed the island in response to a Greek-sponsored coup d’etat intended to unite the island with Greece. In the same month as the TFSC’s declaration, Ercan Airport opened to civilian traffic, and for thirty-five years the main airline that would fly commercial flights to the north would be CTA, a joint venture of Turkish Airlines—Turkey’s national carrier—and the Turki...