Chapter 1

Who Am I to Speak?

I am an ordinary Irish woman, born in the late 1950s in the quiet and very beautiful seaside resort of Ballyheigue, in north Kerry. This village is noted for its six-mile beach, which stretches on to Banna strand. Some famous residents have lived and visited over the years. This is where author Christy Brown, author of My Left Foot, lived out his final days. It is currently home to famed local authors of parish history, namely Micheal O Halloran and Brian McMahon. It is home to my nephew, author Aidan Lucid, whose writing is taking him to greater heights, further afield in Los Angeles. In more recent times, this is also the village where internationally renowned fashion designer Don O’Neill was born and reared.

I was not born with a silver spoon in my mouth: I was fortunate to be born into a poor family. I say ‘fortunate’ as, though life was very poor and very, very simple, everything we got we appreciated, and worked really hard for. For all of my life this start has kept me firmly grounded, never forgetting my humble beginnings, and above all never forgetting where I came from. It has helped me remain humble and compassionate, to respect the feelings of others and appreciate everything I have, upholding honesty as the best policy, all in the name of God, as was the teaching I was reared with.

We moved from my grandmother’s farmhouse to our own home when I was four, to a simple council cottage built on one acre of land, which my parents purchased from a nearby farmer. But encased in that house was a lot of love from and sacrifice on the part of my parents; they turned it from a house into a home. In those days, we would have been known as ‘cottiers’, since the house was provided by the county council on our own land.

At first, we had one light bulb that was moved from room to room as required. Pennies were scarce, and each one was a prisoner. Expenditure was well thought out before it was made. Dad was a labourer and carpenter, and earned little money – there was not much work and wages were low. He co-owned a threshing machine with my uncle, which they would work together in the harvest season, going from farm to farm within our parish and neighbouring parishes. He later worked with a German baroness, who had come to our parish and set up a cottage industry. It gave much-needed employment. Dad made sugán chairs and other crafts, which the baroness sold locally or exported. Mam helped milk a neighbouring farmer’s cows in return for a free gallon of milk daily. She also knitted men’s sweaters for the German cottage industry. There were two main styles, Aran and fisherman’s rib. I made ‘Irish cottages’ using matchboxes and scrap material, receiving one penny for each house delivered. Life was hard but we children were very happy in our world; it was all we knew and we enjoyed it. We made our own fun, as toys were few. We thought everybody lived like this.

Of course, as youngsters we had no idea how our parents ‘went without’ to feed us: Mam used to drink black tea to save the milk for us as children, and dinners were simple, mostly consisting of mashed potatoes (called ‘pandy’) mixed with fried bacon bits saved from the curing of their own pig. Any vegetables we ate were grown in our garden. Our parents were very religious, God-fearing people. We were taught never to pass a Church without ‘saying “Hello” to God’. The rosary and ‘the trimmings’ were very important parts of daily life. My older brother and I would play marbles under the chairs when we got bored during the interminable prayer time, much to the dismay of my parents. The nearby Our Lady’s Well was a frequent and famous place of pilgrimage in my youth, especially on sunny Sundays when we headed to the local beach; the grotto had to be visited first. To this day, that place holds special favour both in the parish and beyond, with the diocesan bishop concelebrating Mass annually on 8 September. It was called The Pattern Day.

I remember when my elder brother was asked to be an altar server: my parents had to pay five shillings for his surplice and soutane. This involved lengthy discussion around the turf fire, as all the money my parents had at the time was five shillings: but they gave it in the name of God. The next day, a letter arrived from Mam’s aunt in New Jersey. It contained $40, an unheard of sum in those days. The letter was tattered and torn, but the dollars remained within: an indication of the honesty that was prevalent at that time. Mam taught us that this was God’s way of repaying them for the sacrifice they had made. This was the environment in which we were raised. I was clothed in hand-me-downs from a wealthier neighbour’s child, and infrequent parcels from mother’s aunt in New Jersey. This included my First Communion dress. I thought this was great – it seemed as if I had lots of new clothes.

I was the second of three living children. Another sibling had been stillborn a couple of years before the birth of my youngest brother, my junior by seven years. In those days we were not told what was happening, but I remember my dad taking the stillborn baby on his bike to be buried, wrapped in a white sheet. It was never spoken about afterwards, but how difficult that must have been for Mam and Dad. There was no counselling for them back then. In later years, I learned that the baby had to be buried outside my paternal family’s tomb, on unconsecrated land, as the baby had not been baptised. Such is the cruelty of man-made rules that existed within our church.

My elder brother and I were the very best buddies as we were close in age, he being two years older. We did the daily walk to school together, and participated in many talent contests and school concerts as singers, with my brother playing the guitar. He was self-taught, and sure, we thought we were great entertainers. These opportunities were important to us as children. My brother went on to launch his own band as his livelihood, and I undertook some voice training when I moved to Dublin.

Primary school is a very mixed bag of memories, mostly negative ones. I went to the local two-teacher school aged four, as I could read and write and was exempted from senior infants. I went straight into first class. We had to keep our lunch on our knees, as rats ran freely through the classroom. School life was difficult, as teachers were hard on students. This was probably the order of the day at the time: corporal punishment was allowed. While that still did not make it right to beat children incessantly, they beat the thrash out of us on a daily basis. The teacher that I had in first class used to lift me by my hair and swing me around. It was probably because of this that my hair fell out in clumps, and I had to be treated by a doctor. No questions were ever asked as to why this had happened, nor any attempt made to seek out if this was abuse. In those days we did not dare tell this at home, as our parents would have thought that we had done something wrong to deserve it. Fear was a big part of every school day, with daily, humiliating reminders of the fact that we were poor. One such episode was when my parents did not have the money for me to go on the school tour to Dublin. I did not really understand what all that meant back then – I was just a child. Of course, we now know, with the benefit of psychological research, that this sort of treatment in one’s childhood, especially before the age of seven, plays a huge part in our well-being as we get older.

I regret not having a sister, but one of my wonderful long-time sisters-in-law fills that space very well. My younger brother was only nine years old when I left home to begin work in Dublin, so I did not have an opportunity to get to know him as well as my elder brother.

I went out to work on Saturdays as a cleaner in the local presbytery. I was ten. That was both great and scary. It was great in that I got paid, which made me feel good, as I could contribute to the family income, but it was also terrifying, as the housekeeper always seemed cross. The next summer, when I was eleven years old, I went to work for the local German baroness. I was the childminder to her grandchildren when they came to visit from France and Germany. This was enjoyable, though not very remunerative. My summer holidays were afterwards spent working in a local business, which comprised a shop, a restaurant and tourist accommodation. This too was great, though we worked hard for seven days a week and twelve hours a day, earning £3 per week. I happily cycled off to work every morning at 7 AM. I met some different and lovely people there. In my childish innocence I thought the people who went on holidays ‘must be loaded’. I had no idea what ‘holidays’ actually meant, as we did not have any. More importantly for me, my £3 subsidised home life, and gained me greater confidence.

Interspersed with this, Dad grew a couple of acres of sugar-beet on conacre or, as it was called locally, ‘scor’. My brother and I hated it, as we would be sent out to hoe and weed the seemingly endless acres every summer. Going to the bog for turf-cutting was much more fun, as we would get a ride on my grandfather’s donkey.

My maternal grandmother was my idol and protector. We lived with her until I was four, and I was her only grand-daughter at the time. In my memory, she was a kind and very talented lady. Nan lived on a farm, but was also a wonderful seamstress, making bed quilts, altar cloths, lace and other crafts, using her Singer sewing machine. She often came to visit after we moved house, and would stay for a few weeks at a time: we hated it when she went home. As a little girl I loved fixing her long silver hair into a bun and helping her with little personal duties. She usually dressed in navy or black, as she was long widowed. She wore a black shawl to Mass, and would always have Silvermints in her pocket. We loved it when she sat beside us, as we were sure of getting a Silvermint. She did not enjoy great health, and walked with a limp. Nan always said to me: ‘You will make a great nurse one day. Be sure and look after old people.’ Since we lived a distance from my paternal grandparents, visits were infrequent but always enjoyable, as there was a large extended household living there. Fatefully, I did become a nurse, and worked in a geriatric hospital for fifteen years. Nan sadly died in her eighties when I was a first-year student nurse, so she never lived to see her dream come true. However, I feel sure she knew from that better place she’s gone to; I hope I lived out the dream she had for me, and made her proud. Her death proved to be a terribly hard time for me, and something I did not come to terms with for several years. There was a family decision made, in conjunction with the parish priest, not to relay the news of her sudden death to me as I was in the middle of my nursing exams: they feared it would affect my academic performance. When I came home the following week, not only did I learn that she was dead, but that she had also already been buried. I never got to say my goodbyes to my nan, a source of great personal regret.

I sat my Leaving Certificate aged sixteen, after which I became very ill and ended up in hospital for three months. I had my appendix removed, but was subsequently found to be anaemic. Treatment for anaemia then was different to today, and it meant that I was hospitalised for that entire summer while they got my iron stores raised to normal.

In September 1973 I left home to begin work as a civil servant in Dublin, at the Department of Posts & Telegraphs in Townsend Street. I was excited but sad, and fearfu, as I was not very worldly. I had never travelled far from my home or even stayed away from it for a single night. Dublin sounded like a distant and scary place. It seemed almost as far away as America. My dad accompanied me on that train journey to Dublin to help me find accommodation. As we parted ways on O’Connell Bridge I was sure he was going to give me some advice. Instead, he simply said: ‘Kathleen, never forget your prayers.’ That spoke volumes to me, and as I got older that advice has had a lasting impression. It has served me well throughout my life, especially during my later years of enforced health difficulties.

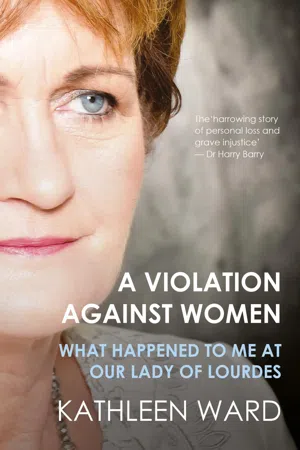

I lived in a six-bed dormitory, several floors up, in a Mountjoy Square hostel for girls, run by the Sisters of Charity. I stayed there for a year. While the sisters were very kind, it was not always a pleasant place as our few worldly possessions often got robbed, presumably by other residents. It would be lonely there at the weekends as most of the other girls went home, but I could not afford this luxury. Staying there did at least enable me to save £16 weekly from my wages, for my nurse training fee of £166. If I was to progress to be a nurse I knew I had to earn the fee, otherwise I could not go. I had by now been accepted for general nurse training at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, commencing March 1975. At the same time I would send £5 home most weeks: this was badly needed, as there was still my younger brother to fend for and send to school.

That is what my generation did: those who had work shared their income with their families at home. I call us ‘the trapped generation’. We, the offspring, sent money home to our parents; now, as parents ourselves, we send money to our kids because of the recessionary times in which we live.

I vividly remember the day of the Dublin bombing. I was to collect a sweater for my brother in Guiney’s on Abbey Street, but forgot the money, so I went back to the hostel. I was at the front door when the bomb went off just down the street, causing death and devastation. Of course, Guiney’s was one of the places most severely damaged, and many lost their lives there. Little did I know then that I would end up living in Monaghan one day, where bombs had gone off on that same day.

In March 1995 I went to the Lourdes Hospital, Drogheda, County Louth, to commence my training in general nursing. My parents could not afford to accompany me on my initiation as they did not have the fare to travel from Kerry. So my cousin, Father Tom O’Connor, a priest in the order of St Camillus who lived in Dublin, was summoned to make the journey with me. I found that a very tough start, as most other girls were there with their families, but I was resilient and determined. The students’ parents were taken in to meet the sisters, but as I did not have my parents there Father Tom and I were asked to wait out in the foyer. Trepidation reigned as I knew nobody, but Father Tom was very reassuring. Over my time there I made many lifelong friendships.

This hospital was set up by Mother Mary Martin, founder of the Medical Missionaries of Mary order of nuns, in 1933. Training was strict, fair and mostly wonderful. Of course, there were times when I found it so tough that I thought, I want out of here, but as student colleagues we helped each other through such times – going home without a job was not an option. In those days we worked on the wards after an initial three-month ‘block/in school’ period called ‘PTS’ (preliminary training session). If we did not pass our exams, we ran the risk of being turfed out. We studied on days off and most evenings after work. In 1978 I graduated as a general nurse. I moved back to Tralee to work at St Catherine’s Hospital that summer, on permanent night-duty. This was a wonderful experience as it was busy. I returned to the Lourdes Hospital in October of that year to begin training as a midwife. This was a year-long course which I enjoyed immensely. I graduated in October 1979 knowing that midwifery was my first love.

Meanwhile, I had fallen in love with a Monaghan man and married in October 1979, two weeks after my final examinations. We moved to Monaghan to live. Peter was a busy shop owner: he sold carpets, beds, window blinds and general household goods. I quickly got work in the local geriatric hospital, St Mary’s, Castleblayney, commencing on Christmas Eve 1979. In those days, you took work when offered, otherwise you did not get a second chance, such was the abundance of nurses available at the time and the shortage of work opportunities. We were coming out of the recession of the 1980s, but it really meant nothing to me as I had never been fiscally privileged. It felt like, by working in a geriatric hospital, I was fulfilling the ambition my nan had had for me. Life was wonderful then: we hadn’t a bob to our name, but that was nothing new. Our new home was very basic, but it was ours. We were happy and had great hopes for the future – since we both had work we hoped we could create a good life. Our many plans for the future included our intention to move back to Kerry in the next couple of years; but to my eternal regret and sadness, and that of my parents, we never did permanently return to Ballyheigue.

Since midwifery was my first love and I was working as a staff nurse in a geriatric hospital due to its proximity, I trained as an antenatal teacher in 1981. I first trained by undertaking an Irish course run by An Bord Altranais in Dublin. I then went to Alston Hall in Preston, England, to complete further training in the British regime. I taught privately and became renowned locally for my teaching. Things never happen without a reason, they say, and this was true for me. My husband’s business suffered serious setbacks at that time, through multiple robberies. Living close to the border, robberies were then common. My teaching skills supplemented our income. My children also loved the class nights as they used to bring the tea, or rather, the biscuits, to the class – and they always managed to polish off the remaining biscuits.

Our first beautiful daughter, Arlene, was born in 1982. She suffered numerous chest infections from an early age, usually ending with antibiotics being prescribed. This quickly led to her developing asthma and requiring lots of inhalers. Her progressive ill health continued in a downward spiral. She was constantly on high doses of medications that made little difference to her condition. When she developed pneumonia her general condition rapidly deteriorated in the most frightening way. It was suggested to me to try reflexology treatment for her recovery. Being medically trained, this suggestion seemed outrageous, as thinking outside the medical model had not been part of my training. After all, she was seeing an expensive private paediatrician on an ongoing basis, and this had to be the only way to go – or so I blindly thought at the time.

But once again the hand of fate beckoned, and when Arlene became more seriously ill at the end of her second year, I decided to try reflexology as a last resort. Allergy testing was included as part of the treatment, and she was quickly cured when certain foods were eliminated. Her therapist encouraged me to undertake the training course and qualify as a reflexologist, even if I were to only use this therapy on the family. The therapy was relatively new, and few people were aware of its existence. My daughter’s experience converted me to holistic medicine. I started my training, and began a beautiful new chapter in my life. I’d got the bug – I was eager to learn more and more. On the reflexology course I met someone who encouraged me to study child psychology, which I duly pursued. While studying for that course I met another person who encouraged me to enrol in a nutrition course. As nurses we were taught the basics of nutrition but developed no in-depth knowledge. I went on to undertake many and various nutrition courses...