![]()

1

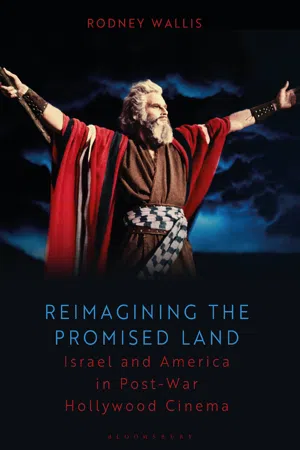

‘God’s Chosen People’: America as Israel in the fifties’ Cold War epic

The establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948 would not serve as the basis of a major Hollywood film until 1960 with the release of Exodus, directed by Otto Preminger. However, Israel was nevertheless existent in Hollywood cinema throughout the twelve years that immediately followed the birth of the Jewish state, appearing most prominently in its pre-historical form as a setting for a number of the Biblical/historical epics that pervaded the era. The Ten Commandments (Cecil B. DeMille, 1956) and Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959) are undoubtedly the two most significant examples of the epic genre’s deployment of the land of pre-historical Israel. The Ten Commandments, a semi-remake of a silent film of the same name directed by DeMille in 1923, was less a film and more of a cultural phenomenon. By the time it was withdrawn from distribution in 1960, The Ten Commandments had supplanted Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939) to claim the number one position on Variety’s list of All-Time Rentals Champs.1 As of late 2015, the film remains among the top-ten all-time grossing Hollywood films after adjusting for inflation.2 In Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies in the Fifties (1997), Steven Cohan describes the significance of The Ten Commandments in the following terms:

During this period no film epitomized the gigantism of the fifties blockbuster better than The Ten Commandments, with its all-star cast, thousands of extras (including the Egyptian army), foreign locations, budget escalations, Academy Award winning special effects, and a final running time of three hours, 39 minutes. The film’s enormous popularity was unmatched even by the other big successful films of this period, to the point where its continuous exhibition during the second half of the decade gave it the aura of a major cultural event in its own right, experienced by the entire nation and transcending the circumstances of ordinary moviegoing.3

Three years after the release of The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur would go on to achieve even greater success. The film grossed $74.7 million domestically and $72.2 million internationally during its initial release, becoming the highest grossing film of 1959 and the second highest grossing film up to that point, behind only Gone with the Wind. Ben-Hur’s commercial success was matched by resounding critical acclaim; the film was nominated for twelve Academy Awards and won a then unprecedented e1even, including Best Picture. Due to the combination of its overwhelming success and its immense scale and production cost (with a budget of $15,175,000 it was, at the time, the most expensive film ever made),4 Ben-Hur has achieved a unique cultural resonance, ultimately becoming a paradigmatic term signifying colossal size and extravagance.5

By the mid-1960s the popularity of Biblical/historical epic had largely dissipated. However, the genre has remained a popular subject for film scholars, for whom it constitutes a form of cultural expression that served to project an idealized notion of American Cold War identity. Speaking of the era’s New Testament epics, Maria Wyke argues:

The United States takes on the sanctity of the Holy Land and receives the endorsement of God for all its past and present fights for freedom against tyrannical regimes (imperial Britain, Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, or the Communist Soviet Union). In such narratives, a hyperbolically tyrannical Rome stands for the decadent European Other forever destined to be defeated by the vigorous Christian principles of democratic America.6

Martin Winkler, in his discussion of epic films set in ancient Rome, similarly asserts, ‘The struggles of the protagonists … against their oppressors develop in purely American terms. Their fights become quests for political independence and spiritual freedom or both; as such they are analogous to actual American history and to Americans’ perception of themselves as champions of liberty.’7 Likewise, in her commentary on The Ten Commandments, Sumiko Higashi contends that the era’s Biblical epics ‘were constructed as public history that foregrounded the rise and fall of empires in a linear development culminating with the founding of America.’8

Building on such scholarship, this chapter argues that The Ten Commandments and Ben-Hur each project an idealized conception of Cold War identity by explicitly constructing ancient Hebrews as modern-day Americans, while simultaneously presenting the Hebrews’ enslavers – be they Egyptian Pharaohs or Roman elites – as stand-ins for contemporaneous totalitarianisms. Here it is crucial to acknowledge that the conflation of American and Hebrew identities in each film should not be understood as a conscious attempt to valorize the then recently established state of Israel. Instead, this conflation functions as a reaffirmation of the Puritan notion of Americans as ‘God’s Chosen People,’ and the American continent as a divinely ordained Promised Land. This opening phase of post-war Hollywood’s deployment of Israel is particularly significant, as it establishes a relationship of parallelism between the United States and Israel that would go on to inform subsequent representations of Israel. Moreover, this phase of Hollywood cinema contributed significant capital to what was the burgeoning alignment of American and Jewish identities within the American cultural imaginary, ultimately making the ground fertile for the blossoming of the special relationship in subsequent decades.

The Ten Commandments as Cold War sermon

According to Rick Altman, the functionality of genre cinema is highly dependent on ‘the interpretive community to which its members belong,’ with text morphing into message, ‘only in the context of a specific audience in a specific interpretive community.’9 As such, prior to discussing the manner in which a particular film from the Biblical/historical epic cycle of the 1950s operated at an allegorical level, it is important to first establish the cultural context of the milieu.

The end of the Second World War ushered in a dramatic reconfiguration of the global geopolitical landscape. The destruction of Western Europe and the defeat of Japan created a power vacuum that would ultimately be filled by two nations governed by diametrically opposed ideologies – the liberal democracy of the United States and the socialist Soviet Union. In March 1947 the president of the United States, Harry Truman, prompted by increasing concerns that the unstable post-war governments of Greece and Turkey would fall prey to Soviet encroachment following British withdrawal from the Mediterranean, delivered an address to Congress in which he framed the contemporary world as being defined by a far-reaching struggle between two alternate ways of life – ‘free,’ represented and upheld by the United States, and ‘totalitarian,’ which was represented by the Soviet Union. Truman asserted, ‘it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation.’10 This speech articulated what would ultimately be known as the Truman Doctrine, which amounted to a renunciation of the United States’ traditional policy of isolationism, and the explicit privileging of the containment of Communism at the subordination of all other geopolitical concerns. According to historian Melvyn P. Leffler, Truman enjoyed the overwhelming support of both the general public and the American media, with his decision to aggressively resist the Soviet Union ‘deemed no less significant than the Monroe Doctrine and the decision to oppose Hitler.’11 The articulation of the Truman Doctrine constituted the US government’s official launching of the Cold War, and its virulent opposition to Communism would go on to serve as the cornerstone of the United States’ international and domestic policy for the next forty years.

With the launching of the Cold War and the subsequent emergence of the ever-present threat of Mutually Assured Destruction, religious adherence and the notion of Americanness would achieve a new level of synonymity. In what Douglas T. Miller and Marion Nowak attribute to ‘insecurity brought on by hydrogen bombs and atomic spies,’ the nation underwent a profound religious revival, with the church serving as ‘the mainstay of traditional values.’12 Bible sales spiked, with The Revised Standard Version of the Holy Bible rated as the non-fiction bestseller in 1952, 1953 and 1954,13 while surveys consistently found that between 95 and 97 per cent of Americans professed a belief in God, with official church membership ranging between 57 and 69 per cent of the population.14

In what was a bold affirmation of Americans as ‘God’s Chosen People,’ in 1954 the United States became a nation – according to its newly modified Pledge of Allegiance –‘under God.’ In 1956 – the year The Ten Commandments was released – the Senate confirmed ‘In God We Trust’ as the national motto. The conflation of faith and democracy in the early part of the fifties played a key role in the nascent Cold War being painted in religious terms, with ‘good’ America playing the role of the defender of the faith against the spectre of ‘evil’ atheistic Communism. In 1951 former Second World War general and future president Dwight D. Eisenhower intoned, ‘It is only through religion that we can lick this thing called Communism.’15 Two years later President Eisenhower proclaimed, ‘Recognition of the Supreme Being is the first, the most basic expression of Americanism. Without God, there could be no American form of government, nor an American way of life.’16 John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State from 1953 to 1959 and the son of a Presbyterian minister, publicly claimed that ‘there is no way to solve the great perplexing international problems except by bringing to bear on them the force of Christianity.’17 Dulles’ sentiments were apparently shared by much of the population, as evidenced by a Gallup poll taken in 1958 that revealed that 80 per cent of the American electorate ‘would refuse to vote for an atheist for President under any circumstances.’18 In addition, the Federal Bureau of Investigation chief J. Edgar Hoover, a notorious anti-Communist and the one man whose power and influence arguably eclipsed that of each of the six presidents he served, also made frequent inferences to the power of Christianity to help win the fight against Communism. Hoover’s bestselling anti-Communist tract Masters of Deceit, published in 1958, asserted that, ‘all we need is faith, real faith …. The truly revolutionary force of history is not material power but the spirit of religion.’19 This was the context in which Hollywood’s cycle of Biblical/historical epic films achieved profound cultural resonance.

While the Cold War would never escalate into a large-scale conflagration between the United States and the Soviet Union, it was nevertheless, to quote Tony Shaw, ‘a total conflict requiring contributions from all sectors of American life.’20 As Shaw details throughout Hollywood’s Cold War (2007), the Cold War was ‘a propaganda contest par excellence,’ in which the combatants deployed ‘words and images, using psychological warfare laced with ideological slogans on an unparalleled scale, as a substitute for guns and bombs.’21 As America’s pre-eminent cultural medium, Hollywood cinema was naturally a primary source of propagandist artillery. This was a situation openly and proudly affirmed by the industry itself; in 1951 Eric Johnston, head of the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America), announced in the Film Daily Year Book that Hollywood was on the front line in the Cold War, describing the role as one ‘that we can fill with credit and distinction as we have with every call in the past, … with ingenuity, with a large dash of daring and a large helping of the sauce of wholesome showmanship.’22 Hollywood’s participation in this heretofore unseen propaganda contest was particularly pronounced from the late 1940s until the end of the 1950s, a period which marked the peak of Cold War tensions. Shaw and Denise Youngblood identify approximately seventy explicitly anti-Communist films produced by Hollywood between 1948 and 1953.23 Meanwhile, films that consciously sold the ideal of ‘people’s capitalism,’ which showed that ‘the fruits of American free enterprise could be enjoyed by all, not just the rich,’ pervaded the remainder of the decade.24

Throughout this period Cecil B. DeMille emerged as one of Hollywood’s leading Cold War warriors. In 1953 DeMille asserted that Hollywood filmmakers ‘have two missions – to fight subversion in our own industry and to make the pictures we produce effective carriers of the American ideals we are pledged to preserve.’25 This imploration came in the wake of a decade of virulent anti-Communist campaigning. In 1944 DeMille served as one of the founding members of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA). The MPA’s statement of principles articulated a resentment of ‘the growing impression that this industry is made of, and dominated by, Communists, radicals, and crackpots,’ and it pledged ‘to fight, with every means at our organized command, any effort of any group or individual, to divert the loyalty of the screen from the free America that gave it birth.’26 One year later DeMille established the Foundation for Political Freedom. This organization regularly sent information to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), the investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives that rigorously investigated suspected threats of Communist subversion or propaganda, and which was responsible for implementing the Hollywood blacklist that effectively ended the careers of hundreds of artists.27 In 1950 DeMille spearheaded a campaign demanding all members of the Screen Directors Guild to take a loyalty oath, which carried with it the implicit threat that those who refused would be blacklisted.28

DeMille’s 1956 version of The Ten Commandments would constitute his most notable cinematic contribution to Hollywood’s propaganda campaign against the Soviet Union. The film tells the story of the Hebrews’ liberation from slavery in Egypt as told in the Book of Exodus, while also including other invented material such as a backstory in which Moses (Charlton Heston) is the favoured son of the Pharaoh...