![]()

1

A Special Need

The more I listened to their recorded performances—of songs composed both by the artists themselves and by others—the more I realized that their music could serve as a rich terrain for examining a historical feminist consciousness that reflected the lives of working-class Black communities.1

—Angela Davis

“I’ve never seen Janet so . . . Black!” my mother proclaimed upon viewing Janet Jackson’s video for “Got ’Til It’s Gone.” The multiple bare-faced “Janets” danced on the screens in Sam Goody at our local mall, The Galleria at Tyler in Riverside, California. I had just turned seven, and my mother reluctantly allowed me to drag her into the store. As much I loved music, my age and religiously conservative Black household limited my engagement with the world. Alternative music did not make its way indoors, at least not until I was twelve. My mother allowed me to drag her into that Sam Goody because it was Janet Jackson and most Black conservative households carry some perceived allegiance to the Jackson family. But, she was not expecting, nor was she comfortable with, the Janet that expressed herself in that video or on the album. My mother’s bewilderment and my excitement came from the fact that in all of the previous Janet eras, The Velvet Rope was the first to showcase Janet at her most different, experimental, and Black.

The first video for The Velvet Rope was set in a club lounge in apartheid South Africa and was Janet’s first video to exclusively feature Black people. “Got ’Til It’s Gone,” included an appearance and rap by Q-Tip and the legendary Joni Mitchell, who remains largely unseen in the video. Janet wore her natural hair for the video in several extended and upright twist-outs covering the crown of her head. The video’s cinematography captures the luminous potential of varying shades of Black skin to soak up light, sweat, water—to not only radiate but also glisten onscreen. I had never seen Black bodies in a moving image look that resplendent, raw, and natural. “Got ’Til It’s Gone” captured Black skin’s potential for soaking up the lime- and moonlight. It was, and remains, one of the most dynamic visuals that I have ever encountered.

The Velvet Rope exhibited Janet’s interest in working with and through Black cultural production, ushered in a more “harder” sound. Black cultural production refers to the process of making art/work in spaces and with individuals racialized as Black. Prior to The Velvet Rope, we all knew Janet was Black and that she came from one of the Blackest families and contributors to twentieth-century Black music. But this Janet was in tune with the blues, hip-hop, and funk—with the other side of being Black that was not the type of “respectable” Black you would be in public. Respectable attitudes in the production and performance of a racialized body advocate for uplifting the race through appearances and sound to appease Eurocentric features and production. Such a production and performance limits the visibility of Black difference. Some Black artists gained visibility by participating in the “dominant” counter-production of respectability, whether or not that counter-production applied to their lives or not. The social imagination of what Black could be was limited. The Velvet Rope brought an image that was not only “different” but very Black to that structure, spearheading new conversations around Black identity politics.

Emerging out of a family that participated in the Motown era, Janet’s formative years inevitably were influenced by the production of Black women entertainers who presented a “respectable, acceptable” portrayal of Black femininity. Respectability politics refer to the self and communal management of Black individual’s social behavior, believing that presentation of the “well-behaved” would usher forth equitable treatment of Black people in the United States. Scholar Lisa B. Thompson writes of this history as the tension between the “circulating ideologies such as the Cult of True Womanhood and the Cult of Domesticity, which emphasized piety, purity, and submissiveness, held promise for revising notions about Black people as immoral.”2 Thus, there is an overwhelming focus on Black women’s bodies as a representative of the race and a deep belief that changing the appearance of Black women through the adoption of respectable qualities would uplift the race and counter those notions of “immoral” behavior.

In her book On Racial Icons, Nicole Fleetwood writes that internal image makers at Motown like Maxine Powell trained and molded entertainers to be the “epitome of upwardly mobile, adult bourgeois charm . . . one that refuted notions of Black excess.”3 This is not to say that the earlier versions of Janet seen on Control, Rhythm Nation 1814, and janet. followed this aforementioned practice pushed forth through the Motown system, but they were visuals that bridged the gap for mainstream white audiences to accept Janet as a pop star in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Janet’s dominance in the media prior to The Velvet Rope was one situated on refuting practices of Black excess, be that in sound or image. This Janet had no fucks to give, conveying her woes through her aesthetics, purposefully deploying citations that were produced by Black culture—natural hair, symbols from the ancestral African tribe of the Akan—and working with emerging hip-hop artists. The Velvet Rope was personal, but the specific Afro-diasporic citation was Janet’s way of linking her personal struggles with shared diasporic political struggles of other Black women. That is what made The Velvet Rope Janet so Bla ck in my mother’s eyes. We walked out of Sam Goody that day with a CD of The Velvet Rope (which I am still baffled that she bought) and a new image of Janet—one with “defiant” hair, piercings, tattoos, different, and very Black. It is an image that I have latched on to from that moment on.

Downright Mean

The press were anticipating Janet’s sixth studio album before the production of The Velvet Rope began. Following the completion of her RCA contract, Janet signed a one-album contract with Virgin for $30 million in 1992, the highest at that time.4 After the success of janet. she renewed her contract with Virgin for a staggering $80 million, which remains one of the highest contractual signing for a recording artist ever.5 To say that Janet was at the top of her career would be a gross understatement. Janet was at the top, period. The Velvet Rope would team Janet up, again, with longtime producing partners Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis in addition to listing production and writing credits to her then (secret) husband Renée Elizondo Jr. for the first time. The public (and press) were startled that the next album would be Janet’s “most personal” yet and would deal with her two-year battle with depression. The press’s reaction was combative: How can you be depressed?6 Janet, who just signed an $80 million record deal. Janet, who is one of the sexiest women in the world. Janet, who was born into one of the most famous entertainment families of all time. You, depressed? I don’t think so, was the collective response.7

In addition, Janet found herself having to “speak” on behalf of Michael’s tumultuous life. She maintained her spotlight and resented being used to gain insight on his experiences. The press read this insistence for autonomy as a rivalry.8 When you’re sixteen, growing up in the shadow of a brother crowned the King of Pop must not have made carving out an identity easy, and yet, Janet did. As a testament to the autonomy that Janet worked so hard to obtain, starting with Control and solidifying it with janet., this book will focus on Janet’s life and her worldview as retrieved from numerous interviews, writings, songs, videos, and anecdotes. I will be neither approaching nor thoroughly considering the worldview of her siblings, specifically Michael.

I did not conduct any interviews for this book but rather approached unpacking the album and its production with available materials: interviews, media documentation, reviews, music videos, and, of course, the album itself. I look at the album for its conceptual properties and metaphors to narrate Janet’s process toward self-actualization. I work with the given properties of the text and expand upon them by bringing historical and theoretical positions that may help clarify or contextualize Janet’s voice, the response, or incidents surrounding the album, which include an unfortunate wealth of media backlash.

The apprehension facing The Velvet Rope began to rise as Janet started the promotional tour for the album. The Velvet Rope is about the need to reconcile with the past, utilizing metaphors around barriers, inclusion, and bondage. Male reviewers were explicitly disinterested in the album’s narrative arc. One of the few interviews where Janet received sensitivity to the album’s content on abuse and neglect came from her interview with Laura B. Randolph for Ebony magazine—a stark contrast to other reviewers who felt that Janet manufactured pain to sell records.9

The interviews and a large majority of the reviews for the album are emblematic of racialized sexism delivered in print. The “bad” press stemmed from men not wanting to affirm women’s issues because to do so would have them address how they are complicit, benefit from, and potentially enable the oppression of women in society. The Velvet Rope was met with “mixed” reviews and attention placed not on what was being said but on her body and her fluctuating weight. In his Rolling Stone interview with Janet for The Velvet Rope, David Ritz notes, “She got her ass kicked. Her metaphors were misunderstood. Word was she was into bondage. Or she was depressed. They said the album wasn’t selling. They said the tour was bombing. The press was hostile and, for the first time in Janet’s career, downright mean.”10

Many reviewers felt frustrated by Janet’s “poeticism.” The suggestion was that if this was her most “personal” album, why wasn’t she “telling” us everything? Such an inquiry is troubling for it places an onus on women to testify their pain in order to be believed. It is not enough to state that you are a victim; we need to know the details and demand that you relive and re-perform that trauma. The problem with the testimony is that it operates under a system that will use your words against you.

The constant need for women to testify their pain, Black women especially, articulates the performance dynamic of the testimony and the fact that performing pain incited by racial or sexual abuse, historically, has been a place of pleasure for others in the United States. I can imagine that Janet’s insistence on ambiguity at times was a foresight of self-preservation. In a BBC “making of” featurette for “I Get Lonely,” she stated the following, “I’ve lost a lot of privacy. I don’t believe in giving it all up.”11 The need to keep some things to herself was a way to not fully participate in the sharing economy that often demands women re-perform their abuse on demand. The Velvet Rope, yes, features Janet at her most vulnerable, her most personal, but also at her most in control regarding the form her “testimony” was going to take.

Aesthetics

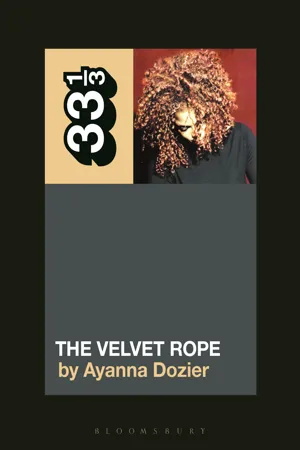

The album cover shows Janet’s roots. Literally. The bulk of Ellen von Unwerth’s portrait of Janet is made up of her hennaed red tresses as she casts her head down, eyes closed, wearing a black long-sleeve shirt against a burgundy backdrop. The portrait is markedly different from janet.’s assertive gaze toward the viewer, with her hands resting upon her mane of curls, coyly smirking at her audience. The Janet on the cover of janet. was hiding something in the truncated image that would be revealed in the September 1993 issue of Rolling Stone that showed a bare-breasted Janet wearing jeans with the hands of her then husband and artistic collaborator, Renée Elizondo Jr., covering her nipples. The Velvet Rope’s packaging and production design was by Len Peltier, Steve Gerdes, and Flavía Cureteu. Interior photography was produced by both Ellen von Unwerth and Mario Testino, with additional tour and promotional singles photography by Renée Elizondo Jr.

If janet. was her “sexual” debut, then The Velvet Rope was her rebellious one. Janet unveiled a physical transformation to match her internal rebellion, which included a series of piercings (septum, nipple, and labia). Her natural hair in tight red curls, a departure from the looser curl pattern audiences grew to associate with her image. Her attire consisted of low-cut black blazers, trousers, bustiers, and the occasional turtleneck, in addition to several visible tattoos—most notably the Sankofa symbol from the Akan culture (located in present-day Ghana) on her right wrist. These liner notes photographs demonstrate that Janet, although melancholic, was not interested in losing the sexual freedom and the need “to accept [her]se...