- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Left and Right

About this book

Originally published in 1976, this title deals with the problem of how we tell left from right. The authors argue that the ability to tell left from right depends ultimately on a bodily asymmetry, such as preference for one or the other hand, or dominance of one side of the brain. This has implications for child development, reading disability, navigation, art, and culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Left and Right by Michael C. Corballis,Ivan L. Beale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Applied Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

We had been flying for three hours. A brightness that seemed to glare spurted on the starboard side. I stared. A streamer of light which I had hitherto not noticed was fluttering from a lamp at the tip of the wing. It was an intermittent glow, now brilliant, now dim. It told me that I had flown into a cloud, and it was on the cloud the lamp was reflected. I was nearing the landmarks upon which I had counted; a clear sky would have helped a lot. The wing shone bright under the halo. The light steadied itself, became fixed, and then began to radiate in the form of a bouquet of pink blossoms.

— Wind, Sand and Stars

ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY

ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY

Saint-Exupéry’s vivid description is wrong in just one detail. The starboard light is green, not red. To have seen “a bouquet of pink blossoms” Saint Exupéry must have been looking at the port wing of the aircraft.

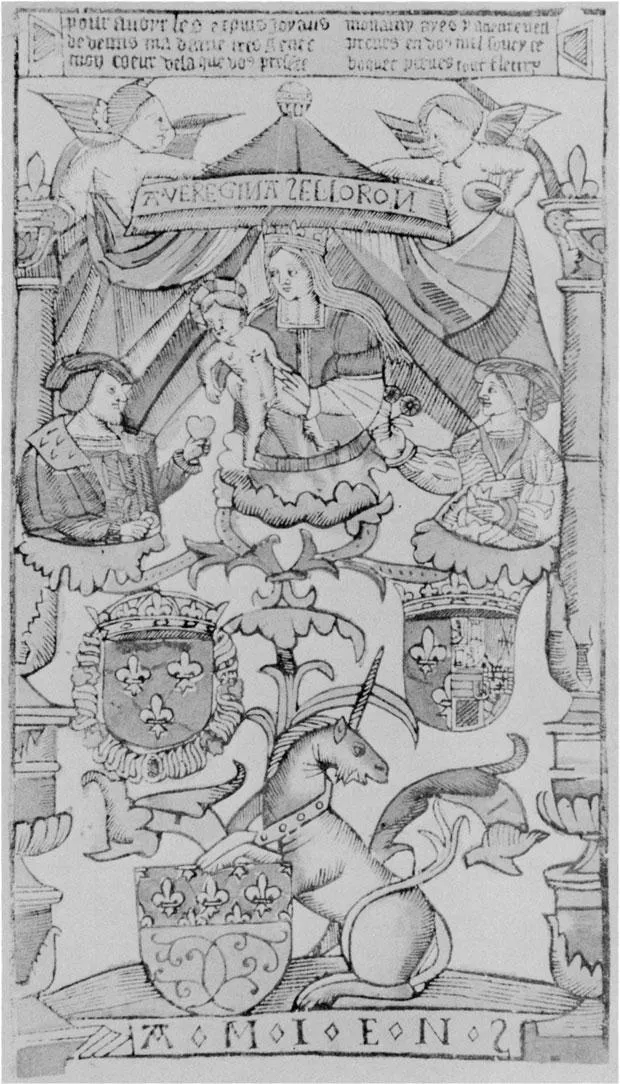

The print shown in Fig. 1.1 is from a woodcut made by an anonymous French master in about 1536. This early example of poster art was probably designed to announce the forthcoming marriage between Francis I and Eleonore of Austria, who are shown exchanging a heart and a rose. The charm of this bold print is somewhat marred by four errors in the orientation of letters; two N’s and two S’s have been reversed. Since mistakes in a woodcut can rarely be corrected, the artist makes each cut with care, so the reversals are probably best accounted for as resulting from confusion rather than from carelessness. The artist’s uncertainty about the orientation of certain letters was no doubt aggravated by the need for the block to be mirror-reversed relative to the print to be struck from it, requiring the letters to be cut in reversed form.1

As these examples illustrate, people are often confused about left and right. The problem is so severe in some that the German psychologist Kurt Elze (1924) coined the phrase “right-left blindness,” suggesting an analogy with color blindness. He tells, for example, of army recruits in Czarist Russia who were so bad at telling left from right that, to teach them the difference, they were drilled with a bundle of straw tied to the right leg and a bundle of hay to the left. Elze maintained, though, that right-left blindness was not simply a matter of low intelligence, claiming that such distinguished men as Sigmund Freud, Hermann von Helmholtz, and the poet Schiller were among those afflicted. Indeed, he even suggested that the problem of left and right might be especially common among the highly intelligent, remarking that subhuman animals appear to have no difficulty.

Elze was actually wrong in claiming that animals can easily tell left from right. In Chapter 4 of this book we shall examine the experimental evidence and find that many species may have considerable difficulty. A real-life example has been documented recently by David F. DeSante (1973). On September 17, 1971 he spent the day on southeast Farallon Island, which lies about 28 miles west of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, California. There, he captured one Tennessee Warbler, on Black-throated Blue Warbler, one Blackburnian Warbler, five Blackpoll Warblers, and two American Red-starts. These birds are generally regarded as typical Eastern Warblers, usually to be found at that time of year in Northeastern United States, some 2500 miles east of the Farallons. Yet so-called “vagrant warblers” have frequently been observed on the West Coast. For his doctoral dissertation at Stanford University, DeSante carefully documented the proposition that these birds are victims of a left–right confusion. Migrating from Central Canada, the birds apparently calculate the direction of flight with respect to a north–south line. The successful migrants head southeast to the Atlantic coast, where they accumulate a large quantity of subcutaneous fat before proceeding on the long overwater flight to the Lesser Antilles or the northern coast of South America. But the vagrant birds fly southwest, in the mirror-opposite direction with respect to the northsouth line, and so fly to the West Coast. It is presumed that most will persist with their confusion and fly out from the coast of California, to perish in the Pacific.

In humans, it is primarily during childhood, and perhaps especially up to the age of five or six years that the confusion of left and right is most acute. Although Elze cites Helmholtz as an example of a person who was right-left blind, we know of no evidence that he had any problem as an adult. However, in a famous lecture which he gave in 1903 on his seventieth birthday, he recalled his inability as a child to tell left from right. With Freud, too, it seems to have been mainly a childhood problem. In a letter to Fliess, he wrote

I do not know whether it is obvious to other people which is their own or others’ right and left. In my case in my early years I had to think which was my right; no organic feeling told me. To make sure which was my right hand I used quickly to make a few writing movements [Freud, 1954, p. 243].

The examples we have considered illustrate something of the nature and range of the problem of telling left from right, which we shall more thoroughly explore in the following chapters. But before we outline the plan of the book and introduce our major themes, we shall digress to consider the nature of mirror images, and what it is that mirrors do. This will enable us to clarify some matters of terminology, and at the same time, we hope, to furnish the reader with some preliminary insight into the left–right problem.

MIRROR IMAGES—AND MIRRORS

First, let us consider what is meant by the term “mirror images.” In two-dimensional space, a pattern can be converted to its mirror-image by reflecting it about a line. For example, the lower-case letters b and d are mirror images because each can be obtained from the other by reflection about the vertical. They may be termed left–right mirror images because they differ only with respect to the left–right orientation, and one can tell them apart only if one can tell left from right. As we shall see, animals and human children find it more difficult to discriminate left–right mirror images, such as b and d, than to discriminate up–down mirror images, such as b and p.

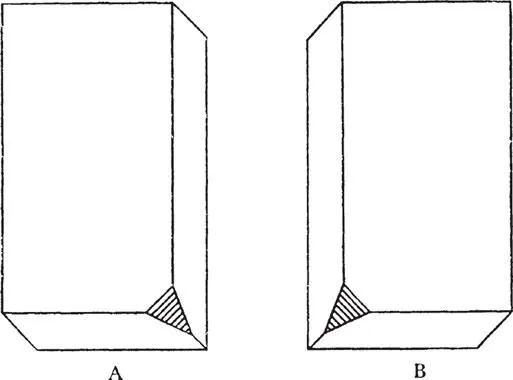

Three-dimensional mirror images are obtained by reflection about a plane. Examples include a left and right shoe, a left and right glove, or the two box-like shapes depicted in Fig. 1.2. Such mirror-image pairs are sometimes called enantiomorphs. The person you see in the looking glass, if real, would be your own enantiomorph. Enantiomorphs may be said to have the same basic shape, at least in the sense that the distance between any two surface points on one is matched by an identical distance on the other. Yet they are also different, in the sense that it is in general impossible to replace one by the other and have it occupy the same space. This “paradox” was discussed by Kant in 1768, and has been a source of fascination to philosophers ever since (see, e.g., Bennett, 1970).

In principle, enantiomorphs can be rotated to identity through a higher dimension. For example, a two-dimensional shape can be converted to its mirror image by rotating it 180° through a third dimension. If you write a b on cellophane and turn it over, it becomes a d. Similarly, three-dimensional enantiomorphs can in principle be made identical by rotating one of them 180° through a fourth dimension. Imagine that, if you will! In “The Plattner Story,” by H.G. Wells, the hero is blown into four-dimensional space by an exploding powder, stays there for a while, and is then blown back into three-dimensional space. When he returns, however, he has been turned around, so that his heart is on the right and he writes backward with his left hand.2

Optically, but not physically, mirror images can be created by mirrors. We can certainly see what the enantiomorphic world would look like and imagine what it would be like to be there by simply looking into a mirror. This of course provides much of the fun of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass. But there is a common confusion about mirrors, which again concerns the left–right dimension. Many people are puzzled by the apparent fact that mirrors reverse left and right, but not up and down or back and front. We look into the mirror and see ourselves, upright, but with the hair-parting on the wrong side, or a mole on the left cheek instead of the right; we hold script up to a mirror, and it is then seen to be virtually illegible, running from right to left instead of from left to right. This, then, is the so-called “mirror problem” (Bennett, 1970): Why should the left–right dimension be singled out for special treatment?

The answer, as Martin Gardner (1967) makes admirably clear, is that it is not! In the direct optical sense, mirrors do not reflect left and right, they reflect about their own planes. If you look into a mirror, what you see is not really a left–right reflection of yourself, but a back–front reflection. To obtain a left–right reversal, you should stand beside the mirror, and for an up–down reversal stand under it or on top of it. Yet, in terms of internal structure, all of these mirror images are the same and constitute your enantiomorph. If you could stand them all upright and make them face in the same direction, they would be seen to be identical to one another.

Reflection about any one plane is equivalent to reflection about any other, plus a rotation and translation. Of the “person” who peers back at you out of the mirror, one could say that he or she is a back–front reflection of yourself; it is as though your nose, mouth, eyes, and so on have all been pushed through to the back of the head, and the back of the head pushed through to the front. One could also say the person is an up–down reflection of yourself, rotated back about a horizontal axis to the upright position. But generally we prefer to say that he or she is a left–right reflection, and we may omit to mention that there has also been a rotation through 180° about a vertical axis.

Why should we prefer this last description, given that alternatives are available? According to Pears (1952), one reason is that we take it tacitly for granted that we normally turn about a vertical axis. We say the confronting mirror image is left–right reversed since we scarcely even notice, or consider it important, that this description also requires a 180° turn about the vertical. We do not say it is up–down reversed because this would require an additional 180° turn about the horizontal, and it is unusual for anyone but an acrobat to rotate about the horizontal. However, this is not the whole story because it does not explain why we do not prefer the optically simpler description that back and front have been reversed, a description which requires no additional rotation at all.

A further and perhaps more important reason for preferring to speak of left–right reversal is that our own bodies are very nearly left–right symmetrical and are therefore largely unaltered by left–right reflection. The physical (as distinct from the optical) description is therefore simpler than in the case of up–down or back–front reflection. The left and right hands might exchange places, but they are both still hands. The only descriptive differences between a man and his left–right reflection concern trivialities; the parting of his hair, the mole on his cheek, the ring on his finger. As Pears (1952) puts it, the two might wear the same clothes. A back–front reflection, by contrast, involves considerable descriptive complexity. The back of the head must gain a nose, mouth, eyes, and so on, while the front must lose these features; there is no simple mapping of one feature into another. The ruptures created by an up–down reflection are if anything even more complex.

Martin Gardner summarizes this way:

A mirror, as you face it, shows absolutely no preference for left and right as against up and down. It does reverse the structure of a figure, point for point, along the axis perpendicular to the mirror. Such a reversal automatically changes an asymmetric figure to its enantiomorph. Because we ourselves are bilaterally symmetrical, we find it convenient to call this a left–right reversal. It is just a manner of speaking, a convention in the use of words [Gardner, 1967, p.35].

It is not only the bodies of humans and animals which are largely unaltered by left–right reflection, however. From the vantage point of an upright observer, the left–right reflection of the world he sees in front of him would still look much like the real world. This is true of the generalities rather than the particulars; an actual scene, if reversed, would not look like the original, but it would still probably look like a real-world scene. A reversed tree still looks like a tree, albeit a different one; the same is true of hills, clouds, houses, and so on. In general, like Alice, we would not feel too disrupted in a world where the left and right were reversed, although particular, familiar objects and scenes might look strange. We may say, then, that there is a considerable degree of left–right equivalence in the way the world impinges on us; an object to the right of us might equally well have been to the left of us, in mirror-image form.

The fact that there is left–right equivalence in the world about us is therefore probably another reason why we prefer to interpret the mirror world as left–right reversed rather than back–front reversed. Indeed, it is left–right equivalence which is probably responsible for the evolution of bilateral symmetry, and for the tendency to confuse left and right. In the natural world, there is generally more to be gained by treating left and right as equivalent than by distinguishing them. We shall develop this theme in more detail in later chapters.

However, left and right are not always equivalent, especially in the man-made as d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Telling Left from Right: Definitions and Procedures

- 3 Implications of Bilateral Symmetry

- 4 Left-Right Confusion: Experimental Evidence

- 5 Mirror-Image Equivalence and Theories of Pattern

- 6 Interhemispheric Mirror-Image Reversal

- 7 The Perception of Symmetry

- 8 The Evolution of Symmetry and Asymmetry

- 9 The Inheritance of Symmetry and Asymmetry

- 10 Development of the Left-Right Sense

- 11 Left-Right Confusion, Laterality, and Reading Disability

- 12 The Pathology of Left and Right: Some Further Twists

- 13 Man, Nature, and the Conservation of Parity

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index