1 A Brief History of Visual Illusions

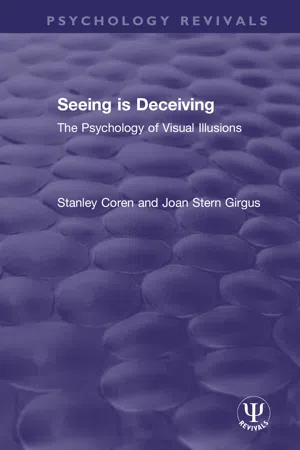

In 1854 a rather unusual paper was published by J. J. Oppel. This paper was unusual because it devoted 10 pages of serious psychological analysis to an array of lines. These lines did not form a complex picture or graph but rather a simple figure shown in Figure 1.1. At first glance this figure appears to be nothing more than two horizontal extents. The upper extent is divided into a number of segments and appears to be slightly longer than the lower. Actually, it is this apparent difference in length that motivated Oppel’s analysis since, as a ruler will quickly demonstrate, the two extents are physically equal. Oppel noted that there had been occasional mention of other instances where the relationships represented in consciousness are systematically different from what might be expected on the basis of direct physical measurement. For those instances that could be represented by lines drawn on paper, he coined the phrase geometrisch-optishe Tauschung which we generally translate as geometrical optical illusion.

Oppel’s paper was not to be an isolated treatment of such illusory phenomena. Soon the literature contained contributions by many of the most important researchers in physics, physiology, philosophy, and psychology, each attempting to explain the existence of such systematically fallacious percepts. The list included such notables as Baldwin, Brentano, Ebbinghaus, Helmholtz, Jastrow, Judd, Lipps, Muensterberg, Titchener, and Wundt. In addition to analysis, these luminaries presented many new configurations in which simple lines drawn on paper led to percepts at variance with reality. The interest aroused was quite intense. The 50 years after Oppel’s treatise first appeared saw the publication of over 200 papers dealing with illusions, and the next 50 years saw this number rise to over 1,000. One might very well wonder why there has been so much fuss over the misperception of the size or shape of a few lines in a drawing.

Perhaps this question is best answered by noting that the only contact we have with the world around us comes through our senses. We put total reliance on the correspondence between our conscious experience of the environment and its physical reality in order to perform such simple tasks as estimating how far we have to jump to get over a puddle without getting wet as well as for such complex life-and-death matters as estimating the distances between ourselves and other vehicles as we drive a car on a highway at mile-a-minute speeds. We have continual verification of the accuracy of our senses. When we reach for objects in view, they are always at the place where they appear to be. We use vision to keep ourselves from bumping into walls, falling over cliffs, or being run down by oncoming cars. Our experience has taught us that our sensory impressions are dependable and trustworthy. This confidence in the veracity of perception has become part of our cultural heritage and is expressed in such common phrases as “Seeing is believing” and “I didn’t believe it until I saw it with my own two eyes.” Thomas Reid clearly stated this position of faith in the senses in 1785 when he wrote:

By all the laws of all nations, in the most solemn judicial trials, wherein men’s fortunes and lives are at stake, the sentence passes according to the testimony of eye or ear, witnesses of good credit. An upright judge will give a fair hearing to every objection that can be made to the integrity of a witness, and allow it to be possible that he may be corrupted; but no judge will ever suppose that witnesses may be imposed upon by trusting to their eyes and ears. And if a skeptical counsel should plead against the testimony of the witnesses, that they had no other evidence for what they declared than the testimony of their eyes and ears, and that we ought not to put so much faith in our senses as to deprive men of life or fortune upon their testimony, surely no upright judge would admit a plea of this kind. I believe no counsel, however skeptical, ever dared to offer such an argument; and, if it were offered, it would be rejected with disdain (Essay 2, Chapter 5).

It is because we have such faith in the ability of our senses to reproduce the external world accurately in consciousness that drawings such as Figure 1.1 are disturbing and excite our interest. The very root of the word used to describe such phenomena manifests this disturbance. The Latin root of the word illusion is illudere, which means “to mock.” Thus these phenomena mock our trust in our senses.

Although it was simply the existence of a discrepancy between percept and reality that began the serious investigation of these phenomena, (as early researchers puzzled over the fact that a few lines drawn on paper could deceive the beautifully complex sensory and perceptual system that allows us to coordinate in the world), it was the theoretical implications that sustained the research. Such phenomena clearly demonstrate that the eye is not a simple camera passively recording stimuli. They provide evidence that perception is an active process that takes place in the brain and is not directly predictable from simple knowledge of the physical relationships. In this context it is not at all surprising that visual illusions comprised an important class of behaviors studied in the last quarter of the nineteenth century by the new science of mental phenomena named psychology.

One can only speculate about which of the common everyday discrepancies among sense, impression, and reality was the first to be noticed. Perhaps it was an afterimage caused by glancing at the sun, which would appear phenomenally as a dark orb hovering in the field of view, always just out of reach. Perhaps it was a stick, half in and half out of a pool of water, which looked bent but felt straight. Surely phenomena of this kind must have presented a dilemma for primitive people whose knowldge about the world was almost completely limited to information gained through direct perception of the environment, without the benefit of any measuring instruments. We do know that by the time we reach the height of the Greek period, perceptual errors and illusions were being ascribed to some inner processing error. Thus Parmenides (ca. 500 B.C.) (Diogenes Laertius, 1925) explains the existence of perceptual illusions by saying, “The eyes and ears are bad witnesses when they are at the service of minds that do not understand their language.”

The Greek writers and philosophers wrote about the problems of perception at great length. In general, they seemed to espouse one of two viewpoints:

1. Sensory inputs are variable and inaccurate, and one of the major functions of the mind is to correct these inaccuracies to provide an accurate representation of the external environment.

2. The senses are inherently accurate and thus responsible for our veridical picture of the environment, and it is the mind or judgmental capacities that are limited.

From the first point of view, perceptual errors arise when the senses are relied on more than the mind, whereas from the second point of view, perceptual errors arise when the mind interferes with the work of the senses. These two opposing viewpoints were both quite popular in ancient Greece and were to dominate thought about perception and cognition for more than 2,000 years. For example, Plato (ca. 300 B.C.) argued that we should talk of perceiving objects through the senses but with the mind, since the senses give only an imperfect copy of the world. Properties of objects, such as their identity, are taken to be the result of the action of the mind or intellect working on the sensory impression. Thus an error of perception could arise only through some mental miscalculation, perhaps due to inattention. The most succinct statement of this position comes from Epicharmus (ca. 450 B.C.) (Spearman, 1937) who says, “The mind sees and the mind hears. The rest is blind and deaf.” An investigator with this orientation would study higher level information-processing strategies rather than the sense organs themselves in order to understand perceptual errors and illusions. The alternative doctrine, based on a total trust in the senses, can be exemplified by a statement from Protagoras (ca. 450 B.C.), who said, “Man is nothing but a bundle of sensations (Freeman, 1953).” In this view any errors or inaccuracies in perception must arise from distortions in the basic materials supplied to the receptors (i.e., the bending or tearing of visual rays).

Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) (Beare, 1931) seems to have adopted a compromise position, incorporating elements of both these viewpoints. He begins by arguing that there are some perceptual qualities that are immediately and accurately perceived by the senses: “Each sense has one kind of object which it discerns, and never errs in reporting that what is before it is color or sound (although it may err as to what it is that is colored or where it is, or what it is that is sounding or where it is).” There are, however, other qualities such as movement, number, figural qualities, and magnitude, that are not the exclusive property of any one sense but are common to all. These qualities, according to Aristotle, require intellectual mediation to assure accuracy of representation. As an example of how perception can be led astray, Aristotle describes an environmental version of the Oppel–Kundt illusion (which is the distortion we showed in Figure 1.1), noting that extents filled with many objects tend to appear greater than empty extents.

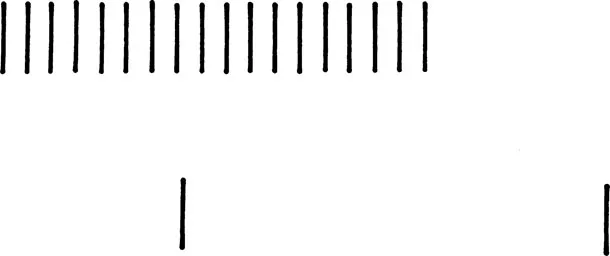

Greek architects of the classical era were also cognizant of the existence of visual illusions. Figure 1.2A shows a schematic diagram of the east face of the Parthenon. Although it looks quite square, this should not be the case. Consider the angle between the roof and the architrave, which forms the configuration schematically shown as Figure 1.2B. This array is actually a variant of the Jastrow–Lipps illusion, which we will describe more fully later. For the moment it will suffice if the reader notes that the horizontal line in the diagram appears to sag slightly away from the point of the angle. On the basis of this illusory distortion, we might expect that the building would look like Figure 1.2C, in which we depict an exaggerated composite of what the percept should be. In fact, however, the building’s proportions were altered to compensate for this distortion. A schematic version of the pattern of these alterations is shown in Figure 1.2D.

Such corrections were apparently made quite consciously. Vitruvius (ca. 30 B.C.) (Granger, 1931) specifically says, “The stylobate must be so levelled that it increases toward the middle with unequal risers; for if it is set out to a level it will seem to the eye to be hollowed.”The fact that such a correction was necessary as well as the magnitude of the correction required, was probably determined on the basis of trial and error.

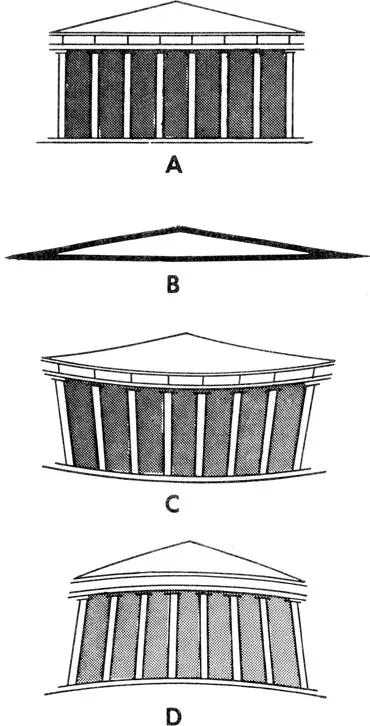

The builders of the Parthenon also corrected another set of distortions. Because of brightness contrast, columns imaged against the dark of the interior are seen as light objects on a dark background, whereas columns imaged against the bright sky are seen as dark objects on the light background. There is an illusory effect known as the irradiation illusion (see pages 41–42), in which bright objects seem larger than dark ones. Figure 1.3 shows how this irradiation illusion would make columns imaged against a dark background look thicker than columns imaged against a light background. To offset this illusion, the Parthenon is constructed so that the angle columns, which are normally seen against the bright sky, are considerably thicker than the columns normally seen against the dark cella wall.

It is thus clear that information about visual distortions played an important role in design in early Greece. To quote Vitruvius again, “For the sight follows gracious contours; and unless we flatter its pleasure by proportionate alterations of the modules (so that by adjustment there is added the amount to which it suffers illusion), an uncouth and ungracious aspect will be presented to the spectators.”

The general trends of thought outlined by the Greek philosophers survived the Middle Ages more or less intact. Thus Descartes’ (1596–1650) position is not that different from Aristotle’s, when he notes that there is both a registration stage and an interpretation stage in the perceptual process. Perceptual error or illusion may intrude at either of these two steps along the road to consciousness. The philosophers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries accepted these two levels of perceptual processing and concentrated their efforts on ascertaining which attributes of perception are given at birth and which are learned through experience. With reference to this issue, Reid (1719–1796) and Kant (1724–1804) argued that almost all knowledge of the external world comes directly through the senses and is interpreted by innate mechanisms, whereas Locke (1632–1704), Berkeley (1685–1753), and Hume (1711–1776) argued that virtually all perceptual qualities are learned through experience with the environment. Regardless of their theoretical biases concerning the importance of experience versus heredity, both groups assumed that some sensory impressions, such as color and brightness, are given and do not require further elaboration. The dispute tended to focus on the relational attributes that allow us to ascertain the size and location of stimuli. For those attributes mediated by innate mechanisms, perceptual errors can arise only if the light rays are interfered with before they reach the eyes or if the neural message is disrupted. On the other hand, for those attributes learned through experience, presumably using the a priori attributes as building blocks, perceptual errors or illusions can also arise because the input has been misinterpreted.

THE EXPERIMENTAL FOUNDATIONS

In 1826 Johannes Mueller (1801–1858) published two books, the first on the physiology and the second on the phenomenology of vision. The second volume contained discussions of a number of phenomena that Mueller called visual illusions. These visual illusions were not distortions found in two-dimensional line drawings. They were such things as afterimages, phantom limbs, and the fact that the impression of white may be produced by mixing any wave length with its complement, with the resultant percept carrying no evidence of the individual components.

Mueller’s major contribution to psychology, however, rests in the several volumes comprising his Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen (1833–1840), some 15% of which was devoted to problems of sensation and perception. It was in this work that Mueller enunciated the doctrine of specific nerve energies, which argues that each nerve is coded for a specific sensation in consciousness. Thus the stimulation of a visual nerve will always lead to the sensation of sight, no matter what the source of the stimulation. As evidence for this, Mueller offers another “illusion,” namely, the fact that the sensation of light often results from mechanical stimulation of the eye such as occurs when it is rubbed or hit.

Mueller reasoned that, since the mind is located in the head, it could have no contact with the external world but only with the neural activity produced by stimulation of sensory receptors. Implicit in the theorizing from antiquity to Mueller had been the assumption of some sympathetic bond between the object and the eye, whereby the internal physiological process could be said to reproduce the external objective reality and its relationships in some fashion. Thus the importance of Mueller’s law of specific nerve energies lies in its explicit denial of any necess...