- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Media Law for Journalists

About this book

This book is both an introductory text and reference guide to the main issues facing journalists today, including social media, fake news, and regulators. The text covers the law of the United Kingdom – including Scots and Northern Irish devolved legislation – as well as human rights and EU laws.

This book covers essential areas such as: privacy, confidentiality, freedom of expression and media freedom, defamation, contempt of court, regulation of the print press and broadcast regulation as well as discussions on fake news and how to regulate online harm. There is a section on intellectual property law, covering mainly copyright. Court reporting and how to report on children, young people and victims of sexual offences receive particular attention in this book with relevant cases in user-friendly format. The engaging writing style is aimed to enthuse students, practitioners and lecturers with plenty of examination and practice materials. The text is packed with extensive learning aids including case studies, boxed notes, sample examination questions, appendices of statutes and cases and a glossary.

It is intended as a complete course textbook for students and teachers of journalism, media, communications and PR courses, focusing on diploma courses, NCTJ examinations and broadcast journalism courses such as the BJTC. The book's international focus would also make it ideal reading for journalists from across the world who are working in the UK. The book presumes no prior legal knowledge.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

The legal systems in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland

1.1 Chapter overview: aims and learning outcomes

1.2 Introduction

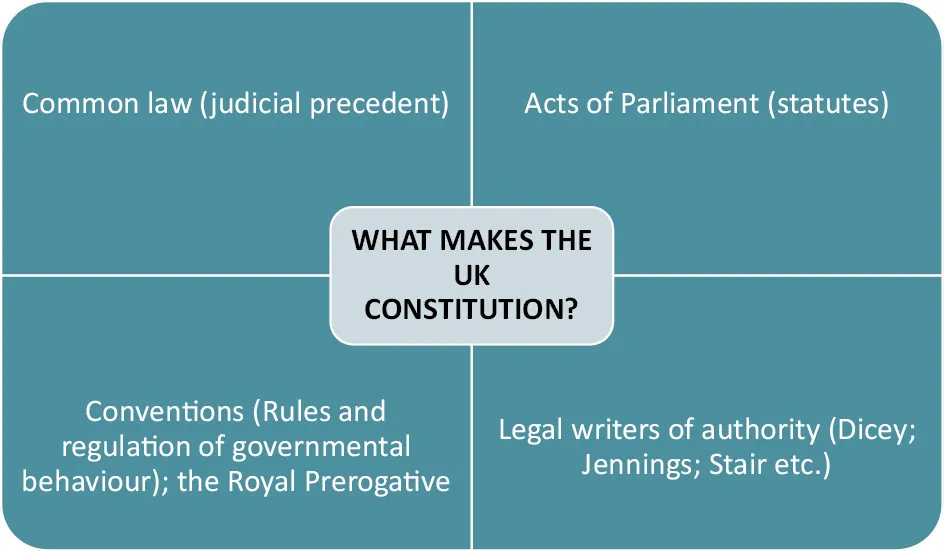

1.3 The UK Constitution and sources of law

Sources of the UK Constitution

| The making and ratification of treaties | ● North Atlantic Treaty 1949. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) is a security alliance of 30 North American and European states. NATO protects the freedom and security of its 30 member states. |

| Recognition of states; the appointment of Ambassadors and High Commissioners abroad | ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Table of cases

- Table of statutes

- Glossary of acronyms and legal terms

- Internet sources and useful websites

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The legal systems in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland

- Chapter 2 Human rights: Privacy and media freedom

- Chapter 3 Defamation

- Chapter 4 Court reporting

- Chapter 5 Contempt of court

- Chapter 6 Freedom of information and data protection

- Chapter 7 Social media and fake news

- Chapter 8 Regulators

- Chapter 9 Intellectual property law

- Bibliography

- Index