eBook - ePub

Society and Psyche

Social Theory and the Unconscious Dimension of the Social

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Providing interpretations and drawing critically from classical and modern social theory, post-structuralism, and psychoanalytic theory, this original study offers an alternative way of thinking about the social and the individual. It offers critical analyses of, among others, Marx, Giddens, Bourdieu, Derrida, Laclau and Mouffe, Castoriadis, Freud and modern psychoanalytic theorists, and considers their roles in advancing our present-day conceptualization of the social and the self. In theorizing that behaviour is both socially determined and autonomous, it avoids the impasses of either individualist or structuralist approaches.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Society and Psyche by Kanakis Leledakis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychoanalysis. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I Posing the Questions

—1— Overture: A Return to Marx

Marx can be seen as a double landmark in the history of social thought. A landmark of the beginnings of this thought — creating moreover what Foucault has called an entire 'field of discursivity'1 — and hence very much a representative of his epoch. And yet, paradoxically, in his contradictions and ambivalence, also a landmark of importance in today's crossroads. In a sense, therefore, a return to Marx is a paradigmatic way to pose certain themes of contemporary relevance while at the same time indicating which theoretical assumptions are to be discarded and which retained.

1. M. Foucault, 'What is an Author?" in P. Rabinow (ed.), The Foucault Reader, Harmondsworth, 1986, p. 114.

The German Ideology is the first, and in many ways the most consistent exposition of Marx and Engels' 'materialism'. This 'materialism' is proposed as an alternative to the idealism of the Young Hegelians who 'consider conceptions, thoughts, ideas, in fact all the products of consciousness, to which they attribute an independent existence, as the real chains of men'.2 In contrast, Marx and Engels want to begin from the premise 'of real individuals, their activity and the material conditions under which they live, both those which they find already existing and those produced by their activity'3 and they assert, in the famous passage, that 'the production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men, the language of real life. Conceiving, thinking, the mental intercourse of men, appear at this stage as the direct efflux of their material behaviour.'4

2. K. Marx and F. Engels, The German Ideology (1846), C.J. Arthur (ed.), London, 1974, p. 41.

3. Ibid., p. 42.

4. Ibid., p. 47.

We have, therefore, 'the mental intercourse', 'mental production', 'consciousness', 'thinking', 'ideas', 'conceptions', in opposition to 'the material intercourse', 'the activity of real individuals', 'the material behaviour'. What is the nature of this opposition? Marx and Engels do not simply invert a causal chain, replacing the Young Hegelians' assertion that ideas determine people's 'real life' with the assertion that it is this 'real life' that determines ideas and consciousness, while retaining a sort of equivalence between the two levels. If thoughts, ideas, consciousness and the like reflect, more or less accurately, the 'materiality' of real life, the Young Hegelians' claim has simply to be completed: it is not enough to change what people think, to combat their unhappiness. People must also, and primarily, change their real life, their 'actual material intercourse'. However, as long as the two levels are seen as two sides of the same coin, it is not particularly relevant which of the two is considered as the determinant one. Since a change in material life implies a change of ideas, given an equivalence of the two, a change in ideas implies — and expresses, on the level of thought — a change in material life. The assertion that the real is reducible to the ideal is by no means affected by a reversal of the proposition while retaining an equivalential assertion.

Marx and Engels do not retain this equivalential assertion. The repudiation of the mental intercourse is made on the name of a material intercourse that is precisely not available to the participating individuals as an idea or consciousness. Marx and Engels' 'real life' is in disjuncture with the thoughts the very persons they live it have. The 'material intercourse' and 'real life' are reflected in thought, consciousness or ideas only in a distorted way (except in specific historical circumstances). Thus the determining character of the material level cannot be deciphered through an analysis of the ideal one. What people think and what they do represent two different modalities, the truth of which cannot be deciphered reciprocally.

What is then the 'truth' of the determinant level, the material one? What is the ontological status of the 'real life of men' as distinct from the 'mental' and what access do we have to the former? We can reconstruct Marx and Engels' answer in two consecutive steps: first, separating this 'material level' not only from 'ideas' but also from 'nature' and considering it as indicating what we may call a 'level' of the social. Second, presenting this social level as emanating from and reducible to the rationality of labour as a transhistorical human attribute reflected in the development of history.

Marx and Engels make immediately clear that the 'material intercourse', which is the 'language of real life', corresponds to 'production': '[Men] begin to distinguish themselves from animals as soon as they begin to produce their means of subsistence, a step which is conditioned by their physical organization.'5 Yet the level of production is not seen as directly determined by this 'physical organization' within which production is carried out: 'By producing their means of subsistence men are indirectly producing their actual material life.'6 Production is only indirectly reducible to the natural environment. Marx and Engels' analysis is focussed on production while the natural environment, as also the biological nature of man, remain on the background as limits rather than as the actual determinants of production, limits which are acknowledged but not discussed. While imposing 'definite conditions'7 the material/natural environment is not determining, in a reductive way, the 'real essence of man'. The mode of production ('mode' referring simply to the form of production) is something more than a reflection of these natural limits: 'The mode of production must not be considered simply as being the production of the physical existence of the individuals. Rather it is a definite form of activity of these individuals, a definite form of expressing their life, a definite mode of life on their part. As individuals express their life, so they are.'8

5. Ibid., p. 42.

6. Ibid., emphasis added.

7. Ibid., p. 47.

8. Ibid., p. 42.

Production as 'a definite mode of life', is precisely a characteristically human activity, not a reflection of nature. The counterposition of production, therefore, as 'material activity and materia! intercourse of men', to 'forms of consciousness', is not a distinction between nature and thought. The term 'matter' retains its traditional philosophical meaning, as the outside, the negation of thought, what is either opaque to it or only partially penetrable. However, the 'material' for Marx and Engels, while still the outside of thought, is not reducible to a closed, mute and determinant nature. It refers rather to a level of activity specifically human: production. Hence we have a threefold distinction:

nature — production — thought

a distinction in which a discontinuity is implied between each of the three terms. We could indicate as 'social' the level that production defines, while recognizing that 'thought' is also social but of a modality somehow 'different' from that of'production'.9

9. Traditional references to Marx and Engeis' materialism tend to concentrate on the irreducibility of nature to thought, thus obscuring the specificity of the level of production that is the primary aim of Marx and Engeis' discussion. Production, while differentiated from thought, is equally differentiated from nature. Such interpretations effect a naturalistic reduction of the level of production that is in no way present in Marx and Engeis (an example is S. Timpanaro, On Materialism, London, 1975).

In Marx's later writings the distinction between nature and production becomes more explicit and clear. Instead of the variations of the term 'intercourse'10 which we have in The German Ideology, the term 'relations of production' is introduced in opposition to the 'forces of production', the latter referring to the actual natural/ environmental/technological elements. In the famous words of the '1859 Preface':

10. Verkehr was rendered as 'intercourse', Verkehrsform as form of intercourse, Verkehrsweise as mode of intercourse, and Verkehrsverhaltnisse as relations or conditions of intercourse (see the editor's note in The German Ideology, p. 42).

In the social production of their life, men enter into definite relations, that are indispensable and independent of their will, relations of production which correspond to a definite stage in the development of their material productive forces. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness.11

11. K. Marx, preface to 'A contribution to a critique of political economy' (1859), usually referred to as the '1859 Preface'. The translation here is in K. Marx and F. Engels, Selected Works, 2 vols, London, 1953, vol. 1, p. 329.

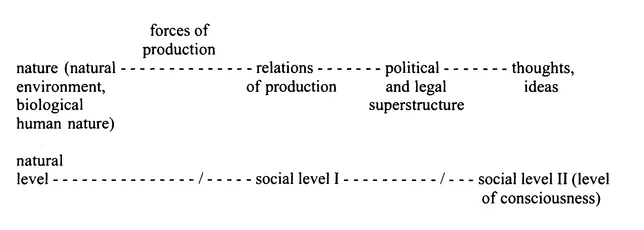

This passage is revealing. It clearly dissociates the actual productive 'forces' from the 'relations' of production, the superstructure, and the latter from the 'forms of social consciousness'. Thus the three levels can be presented as:

Figure 1

The forces of production are the mediating element between the level of nature and the relations of production. These relations, together with the 'political and legal superstructure' are in turn separate from the 'forms of consciousness'. It is this intermediate level that can be termed the 'social level I' as distinct from and not reducible to the — also social — level of consciousness (which can be designated as social level II).

Once a specificity is assigned to this 'first' level of the social, however, the question of how it is to be theorized arises. Since the mode of production is the determinant instance of this level, it is through an analysis of the modality of production that its modality has to be sought. We can see Marx's subsequent work as just such an attempt to define this modality of production.

Early on one possibility is ruled out: that of conceiving production as the result of interaction between individuals, in the manner, for example, of classical political economy. The repeated attacks of Marx against Robinsonades are well known:

The solitary and isolated hunter or fisherman, who serves A. Smith and Ricardo as a starting point, is one of the unimaginative fantasies of the eighteenth century romances [. . .] No more is Rousseau's social contract, which by means of a contract establishes a relationship and connection between subjects that are by nature independent [. . .] The prophets of eighteenth century saw the individual not as a historical result but as the starting point of history; not as something evolving in the course of history but posited by nature.12

12. K. Marx, 'General introduction to Grundrisse' (1857), usually referred to as the '1857 Introduction'. The text here is in the appendix to Marx and Engels, The German Ideology, p. 124.

The historicity of the individual is continuously stressed. Not only do individuals not determine production through their interaction, but their very individuality is a historical product: 'Man is only individualised through the process of history.'13

13. K. Marx, Grundrisse (1858), D. Mclellan (ed.), London, 1980, p. 96.

Advancing on the rejection of individualism, Marx in his analysis of the capitalist relations of production in Capital specifically sees the individual as part of the greater structural whole of production.14 Capitalist production is a structured whole that incorporates commodities, money and capital as well as capitalists and workers, all connected together in a circular relationship, and in a continuous flux. The elements of the system acquire their significance within the totality of the system (anticipating thus a relational definition of structure):

14. L Althusser's importan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I: Posing the Questions

- Part II: Structuration and Indeterminacy

- Part III: Psyche and Society

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index