- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment

About this book

This volume examines the varied ways in which the senses were perceived afresh during the Enlightenment. In addition to introducing new philosophical and scientific models which sometimes upended the classic hierarchy of the senses, this period witnessed major changes in living and working habits, including urbanization, travel and exploration, the invention of new sonic and visual media, and the rise of comfort and pleasure as values that cut across a range of social classes. As this volume shows, those developments inspired a wealth of sensorially stimulating styles of design, art, music, poetry, foodstuffs, material goods and modes of worship and entertainment.

The volume also demonstrates the period's countervailing concern with managing the senses, evident in fields like natural philosophy, medicine, education, religion, and public hygiene. Finally, it explores some of the Enlightenment's desensualizing tendencies, like the separation of sensuous body from discerning mind in certain arenas of science and manufacturing, and the late 18th-century shift away from a politics of publicity, or intense visual and aural scrutiny, toward the secret ballot.

A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment presents essays on the following topics: the social life of the senses; urban sensations; the senses in the marketplace; the senses in religion; the senses in philosophy and science; medicine and the senses; the senses in literature; art and the senses; and sensory media.

The volume also demonstrates the period's countervailing concern with managing the senses, evident in fields like natural philosophy, medicine, education, religion, and public hygiene. Finally, it explores some of the Enlightenment's desensualizing tendencies, like the separation of sensuous body from discerning mind in certain arenas of science and manufacturing, and the late 18th-century shift away from a politics of publicity, or intense visual and aural scrutiny, toward the secret ballot.

A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment presents essays on the following topics: the social life of the senses; urban sensations; the senses in the marketplace; the senses in religion; the senses in philosophy and science; medicine and the senses; the senses in literature; art and the senses; and sensory media.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment by Anne C. Vila in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia social. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

_____________________________________

The senses have, by now, thoroughly infiltrated the study of social life in the eighteenth-century West. The Foul and the Fragrant, Tastes of Paradise, Intimate Vision: such book titles suggest that we are now routinely called upon to consider the era of the Enlightenment in sensual terms. The assumption underlying all these works of scholarship is not only that sensory experience was different in the past, but that the senses mattered then in ways that it is sometimes hard to fully feel now. Sensory experience was vital to questions of taste, social distinction, knowledge production, and faith, not to mention the rhythms of everyday life. Indeed, in the view of many scholars, the eighteenth century distinguished itself as an age of sensory excess that it is historians’ task to recapture for audiences today.

Except, that is, when it comes to politics. The key story that we continue to tell about public life in the eighteenth century—the coming of revolution and the first experiments with democracy in the modern world—has been noticeably untouched by the flowering of sensory history even as the sensual has saturated other historical domains. Perhaps this is because we still tend to think of politics as a largely abstract business, a matter of ideas and concepts more than bodily sensations. Or perhaps this is an effect of the rapid rate of change we associate with the political, especially in revolutionary eras; sensory experience seems to evolve according to the slower rhythms of custom and social practice. Whichever is the case, what follows is an effort to rethink, from the vantage point of the history of the senses, a key element of the standard narrative of the introduction of popular sovereignty under the aegis of the French Revolution. By rereading the advent of democracy, and especially the act of voting, in light of changing notions of secrecy and exposure, or sensory deprivation versus openness to eyes and ears, we can observe aspects of this moment of rupture that have long remained opaque to us—despite our contemporary commitment to the idea of transparent governance. Ideally, we also gain a model for how the history of the public domain might be fruitfully woven together with the history of the senses.

The initial part of this chapter will sketch the very different roles accorded to the senses in structuring the social life and then the political life of Europe and its principal colonies during the final century of the Old Regime. The latter part will then try to account for two breaks in this political-sensory regime that occurred in France near the eighteenth century’s close. The first is the sudden (and well-documented) turn to maximal transparency as political practice between 1789 and 1794. The second is the much less often noted but equally significant turn back to a compromise between sensory openness and desensualized privacy that occurred in 1795: the year of the introduction of that odd phenomenon, the publically administered secret ballot, with which we still live.

*

Any attempt to capture the texture of life in eighteenth-century Paris, London, Amsterdam, Milan, Madrid, or Boston requires attention to smells, noises, vapors, and a kaleidoscopic array of sights that we now only imagine with difficulty. In much of Europe and its overseas outposts, a growing proportion of people left the more open, quiet spaces of farms and villages to move to urban centers. As a result, the already crowded streets of leading cities and towns seemed to contemporaries—and thus to us, reading their words retrospectively—to suddenly teem with human bodies, along with animal bodies and all manner of work, material goods, transport, dirt, and attractions, in very close proximity. For eighteenth-century elites, it became something of a cliché to describe the lives of the urban poor by evoking the myriad sounds of the city (animals braying or being slaughtered, church bells pealing, the shouting in the marketplace of criers and hawkers of goods, the singing of drunks); its strong odors (human excrement, rotting food, horse dung, and the like); its chaotic and often ugly sights; and the feeling of bustle and of restricted movement and space that was thought to be characteristic of the new urban experience (Cockayne 2007; Corfield 1990; Cowan and Steward 2007; Farge 1979, 2007; Garrioch 2003). We read of the sensory pleasures of explicit hedonism: singing, eating, drinking, sex. We read too, especially in the writings of moralists and reformers, of dismay over sewage, smoke, the ailing indigent, and other sensory abominations; such affronts were the starting point for many of the urban reform movements of the later century, such as the rise of new forms of sanitation and lighting (Barles 2005; Corbin 1986; Frey 1997; Koslofsky 2011; Madiment 2007; Melosi 2000). As Emily Cockayne explains in her evocatively titled Hubbub: Filth, Noise and Stench in England, the streets of eighteenth-century English cities were rife with “nuisances and irritants” in sensory form (2007: 230). The dwellings of urban workers, moreover, kept out little of this exterior world. For the cramped quarters of city residents too were filled with sound, odor, and close contact with the bodies of others.

But it was not only the world of the urban poor that constituted a veritable sensory bazaar in the eighteenth century. At the other end of the social scale, Europe’s nobles and the members of Europe’s great courts also distinguished themselves by their sensory trappings, albeit largely ones designed to express maximum distance from the world of their social inferiors. This was, after all, the great age of luxury goods, understood to be sources of both bodily contentment and social prestige for those who owned or consumed them (Berg and Clifford 1999; Berg and Eger 2001; Bremer-David 2011). Consider the design of France’s and indeed, continental Europe’s greatest eighteenth-century interiors, with their growing differentiation between the spaces of public and private life. Inside these great homes, fine materials—velvet, silk, precious stones—appealed to the touch as well as the eye, covering ceilings, walls, furniture, and selves with conduits for pleasure-producing sensations. Pianos, clavichords, and spectacular clocks that chimed or chirped on the hour made abstract sound—in addition to that generated by animated, polite conversation—a regular feature of daily life. Delicate porcelain services added to the pleasure of imbibing strong, fashionable beverages like coffee, tea, and cocoa, all sweetened with an imported and ever more highly desired complement called sugar. Large fireplaces allowed for warming of the body. Delicate handheld fans and large windows, not to mention sofas for reclining, made possible cooling via comfortable breezes. Perfume masked the smells of bodies or streets, replacing them with strong floral fragrances and musk evocative of the garden instead. And in libraries, sitting rooms, and dining rooms alike, occupants’ eyes were tempted to steal a glance in all directions at once: toward elaborate patterned rugs, curtains, and upholsteries; toward large ornamental mirrors, chandeliers holding multiple candles, and gold filigree and metalwork that added light and visual play; toward paintings and tapestries that very often took sensual pleasure as their very theme (Girouard 1993; Whitehead 2009; on specific commodities: Melchoir-Bonnet 2001; Roche 1989; Schivelbusch 1993). Rococo style turned strolling, dancing, swinging, bathing, flirting, and similar pleasures into both its central subject matter and its stylistic inspiration in terms of its evocation of play (Levey 1985). Consider a canvas like Nicolas Lancret’s A Lady in a Garden Taking Coffee with some Children 1742) in which the central image is the very act of smelling and tasting as a child takes a spoonful of coffee from her mother in an idealized garden filled with flowers, fountains, and other sensual delights. We are a far cry here from the painted warnings of the dangers of gluttony and luxury that pervaded the vanitas imagery of the previous century (Jütte 2005: Ch. 4).

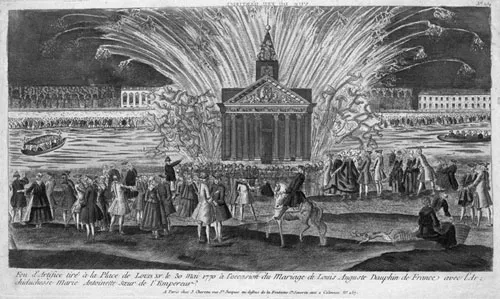

It was Louis XIV’s Versailles, built at the close of the seventeenth century as a kind of monument to sensation, which set the standard for the great houses of Europe well into the eighteenth century. Louis XIV and his legions of designers were not content simply to turn the statuary, jets d’eau, halls of mirrors, and great vistas of his palace and park into feasts for the eyes. They also endeavored to impress French nobles and foreign dignitaries alike by making his home into a setting for spectacles that would have multi-sensory appeal (Burke 1994). From brilliant firework displays, to full-length ballets, to elaborate banquets, classical French taste offered a rival sensory arena to that of Catholic mass (which was also a regular feature of life at Versailles). Such spectacular entertainments were copied all over Europe well into the eighteenth century. In fact, by the last decades of the Old Regime, the appeal of such endeavors had begun to spill out from grand private homes into urban settings more generally, as opera and ballet became, from London to Vienna, public, commercial phenomena, at once aesthetic and social, and open to all who could afford the price of a ticket (Hall-Witt 2007; Johnson 1996).

For those in the middle socially, with little chance of creating their own mini-Versailles but eager to distinguish themselves from the urban or rural poor, such novel late eighteenth-century pleasures as opera-going, but also bathing in the sea, visiting coffeehouses or restaurants, and attending public, scientific displays with an emphasis on the experiential, also made sensory pleasure a feature of what was just coming to be called bourgeois life (Brewer 1997; Lowe 1982; Seigel 2012; on specific forms of bourgeois entertainment: Bensaude-Vincent and Blondel 2008; Cowan 2005; Delbourgo 2006b; Ellis 2004; Spang 2000; Walton 1983). So did consumer goods like fine fabrics and spices that were, by the end of the century, no longer beyond the reach of many urban people even when those objects originated in exotic climes or distant colonial outposts (Brewer and Plumb 1982; Crowley 2001). These were items to be used in the home as objects of private sensory pleasure as much as for public display. In northern, Protestant Europe especially, a nascent middle class fostered an ethics of restraint, of not calling too much attention to itself by means of extravagance or libidinal indulgence. But we should hardly imagine asceticism as the dominant value here; Europe’s new “middling sorts” distinguished themselves as much by inventing a culture centered on leisure-time entertainment, comfort, and consumption as by establishing a new relationship to the means of production. Sensuality of a very particular sort would soon become a part of bourgeois self-definition.

Indeed, the very idea of “taste” as it emerged in the eighteenth century and eventually became the focus of the new science of aesthetics was closely tied to sensory distinctions among different social classes. At its base, taste was related to the body. What the truly tasteful had in abundance, according to eighteenth-century commentators, was an innate sense of “tact” or a fine touch (Dickie 1996; Ferry 1990; Gigante 2005; Tsien 2012). In the same way, literary works that met with favorable receptions could be described as goûté or savored, just like a fine steak. This was not only a matter of metaphor. For eighteenth-century theorists, to have good taste was, at its root, to know “what pleases our senses,” as one mid-century French critic put it. And yet, as Voltaire was to point out in his famous article “Taste” in Diderot and D’Alembert’s influential Encyclopédie (1751–65), possessing this perceptual capacity was not always sufficient to mark one as a true person of taste. Taste in art or literature, Voltaire explained, did indeed operate much like the physical sensation one experiences in eating: “It discriminates as quickly as the tongue and palate, and like physical taste it anticipates thought … it is sensitive to what is good and reacts to it with a feeling of pleasure, it refuses with disgust what is bad.” However, Voltaire went on to point out, taste by itself is liable to make errors, so “it needs practice to develop discrimination,” which is to say, cultivation or training. Good taste was the prerogative of the truly tasteful, a social category more than a physiological one. Bad taste, by contrast, signified a lack of refinement in one’s person but also in circumstances and breeding.

Increasingly, these sensory distinctions had a gendered dimension as well. Women began to lead the way in the realms of fashion and interior design, linking femininity with heightened sensual pleasure: bright colors, elaborate adornment, refined smells. In this way, a second set of hierarchical oppositions was solidified. The senses, too, were used to establish a growing conceptual chasm between the decorative, bodily sphere that properly belonged to women, on the one hand, and the realm of male reason and disembodied, sober, and immaterial ideas, on the other (Chartier 1993; Classen 2012: 71–92).

*

By this logic, it followed that there remained one central domain of life in Old Regime Europe where this emphasis on sensory pleasure did not hold sway, at least in theory. That was the world of politics and statecraft. This is not to say that the monarchs of eighteenth-century Europe did not keep a close eye on their subjects as well as their competitors. We know that all early modern European states, including Great Britain, were rife with networks of police, spies, and censors of various kinds, listening and peering about for useful information relevant to state security. Michel Foucault, in particular, has drawn our attention to the disciplining gaze of the expanding state apparatus, beginning with what one historian calls the “panoptic monarchy” of the all-seeing Louis XIV (Foucault 1977; Smith 1993: esp. 412). Moreover, elaborate ceremonies, including ceremonies of information designed to convey the majesty and power of the crown, remained a feature of statecraft well into the eighteenth century—even if witnessed by a diminishing few courtiers in close proximity and now largely denuded of bodily contact, including the traditional royal touch (Classen 2012: esp. 158–9, 165–6; Fogel 1989; Giesey 1987). It can hardly be called coincidental that ballet and opera, with their goal of overwhelming the eyes and ears of their audiences, in part by displaying the feats of other human bodies, flourished first as courtly entertainments for an international political and social elite. Yet when it came to the business of governing, we find in the eighteenth century—with the partial exception of England and its colonies—a trans-European culture that largely prized secrecy and closed doors.

From the literal masking of dignitaries in Venice to the ideology of absolutism, with its emphasis on the secrets du roi, in France, traditional early modern continental statecraft depended on the idea that affairs of state needed to be hidden from the prying eyes and ears of the public (Kantorowicz 1955; Snyder 2009: esp. Ch. 4; specifically on Venice: Johnson 2011; on France: Schneider 2002). To maintain secrets or to dissimulate and feign, whether about affairs of state or of the heart, was understood to be a vital skill for those in possession of power and eager to maintain it (Elias 1978, 1982). Visibility at the symbolic level was not to be translated into accessibility, or real visibility in the everyday sense, whether for kings or for their closest advisers. Good governance, which w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Preface

- Editor’s Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Powers, Pleasures, and Perils of the Senses in the Enlightenment Era

- 1. The Social Life of the Senses: A New Approach to Eighteenth-century Politics and Public Life

- 2. Urban Sensations: Motion and Commotion in Eighteenth-century Cities

- 3. The Senses in the Marketplace: Coffee, Chintz, and Sofas

- 4. The Senses in Religion: Listening to God in the Eighteenth Century

- 5. The Senses in Philosophy and Science: Blindness and Insight

- 6. Medicine and the Senses: The Perception of Essences

- 7. The Senses in Literature: Pleasures of Imagining in Poetry and Prose

- 8. Art and the Senses: Experiencing the Arts in the Age of Sensibility

- 9. Sensory Media: Communication and the Enlightenment in the Atlantic World

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Copyright