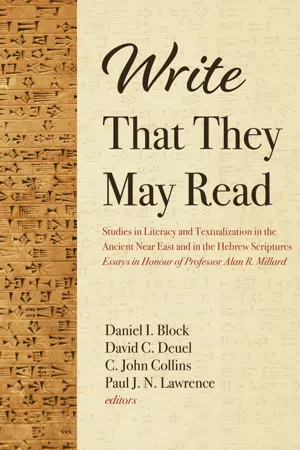

Write That They May Read

Studies in Literacy and Textualization in the Ancient Near East and in the Hebrew Scriptures:Essays in Honour of Professor Alan R. Millard

- 538 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Write That They May Read

Studies in Literacy and Textualization in the Ancient Near East and in the Hebrew Scriptures:Essays in Honour of Professor Alan R. Millard

About this book

Write That They May Read is a collection of essays written in honor of our mentor, friend, and fellow scholar, Professor Alan R. Millard. Respectful of his contribution to our understanding of writing and literacy in the ancient biblical world, all the essays deal with some aspect of this issue, ranging in scope from archeological artifacts that need to be "read," to early evidence of writing in Israel's world, to the significance of reading and writing in the Bible, including God's own literacy, to the production of books in the ancient world, and the significance of metaphorical branding of God's people with his name. The contributors are distributed among Professor Millard's peers and colleagues in a variety of institutions, his own students, and students of his students. They represent a variety of disciplines including biblical archeology, Egyptology, Assyriology, Hebrew and other Northwest Semitic texts, and the literature of the Bible, and reside in North America, Japan, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Germany. Write That They May Read contains contributions by: Section 1: Artifacts and Minimalist Literacy1. "See That You May Understand": Artifact Literacy--The Twin-cup Libation Vessels from Khirbet QeiyafaGerald Klingbeil, Research Professor of Old Testament and Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Andrews UniversityMartin Klingbeil, Professor of Biblical Studies and Archaeology, and Associate Director, Institute of Archaeology Southern Adventist University 2. Ketiv-Qere: The Writing and Reading of EA 256 and Its Place in Reflecting the Realia of Power and Polity in the LBA-IA Golan and PeripheriesTimothy M. Crow, Senior Lecturer in History, University of Akron; Professional Fellow Old Testament, Ashland Theological Seminary 3. Another Inscribed Arrowhead in the British MuseumTerrence C. Mitchell†. Former Keeper of Western Asiatic Antiquities, The British Museum, London, England 4. Earliest Literary Allusions to Homer and the Pentateuch from Ischia in Italy and JerusalemPaul J. N. Lawrence, Translation Consultant, Summer Institute of Linguistics International 5. The Etymology of Hebrew l?g and the Identity of Shavsha the ScribeYoshiyuki Muchiki, Professor of Biblical Theology, Japan Bible Seminary, Tokyo Section 2: Artifacts and Official Literacy6. The Writing/Reading of the Stone Tablet Covenant in the Light of the Writing/Reading/Hearing of the Silver Tablet TreatyGordon Johnston, Professor of Old Testament, Dallas Theological Seminary 7. For Whose Eyes? The Divine Origins and Function of the Two Tablets of the Israelite CovenantDaniel I. Block, Gunther H. Knoedler Professor Emeritus of Old Testament, Wheaton College 8. Write That They May Judge? Applying Written Law in Biblical IsraelJonathan Burnside, Professor of Biblical Law, Law School, University of Bristol. 9. "And Samuel Wrote in the Book" (1 Samuel 10:25) and His Apology in First Samuel 1-15Wolfgang Ertl, Dozent am Bibelseminar Bonn, Bornheim/Germany; Associate Professor of Old Testament, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 10. "For the one who will read it aloud will be able to run with it" (Habakkuk 2:2c)David Toshio Tsumura, Professor of Old Testament, Japan Bible SeminarSection 3: The Rise of Literary Literacy11. The History and Pre-History of the Hebrew Language in the West Semitic Literary TraditionRichard E. Averbeck, Professor of Old Testament and Semitic Languages, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School 12. Divine Action in the Hebrew Bible: "Borrowing" from Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and "Inspiration"C. John Collins, Professor of Old Testament, Covenant Theological Seminary13. Encoding and Decoding CultureJens Bruun Kofoed, Professor of Old Testament, Fjellhaug International University College,14. No Books, No Authors: Literary Production in a Hearing-Dominant CultureJohn H. Walton, Professor of Old Testament, Wheaton College15. The Discovery of the Book of the Law in 2 Kings 22:8-10 in the Light of the Literary Renaissance of the Eighth to Seventh Centuries in the Ancient Near East James K. Hoffmeier, Emeritus Professor of Old Testament and Near Eastern Archaeology, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School16. "Read This Torah" (Deuteronomy 31:11): The Importance and Function of Israel's Primary Scripture in Early Spiritual GrowthDavid C. Deuel, Academic Dean Emeritus, The Master's Academy International17. What is a "Messianic Text"? The Uruk Prophecy and the Old TestamentErnest C. Lucas, Vice-Principal Emeritus, Bristol Baptist College, UK18. "Joshua 24 and Psalm 81 as Intertexts"Cheryl Eaton, PhD Candidate, Trinity College, Bristol 19. "Much Study is a Weariness of the Flesh": To Read or not to Read in Ecclesiastes 12:11-12Knut Heim, Professor of Old Testament, Denver SeminarySection 4: Metaphorical Literacy20. Belonging to YHWH: Real and Imagined Inscribed Seals in Biblical TraditionCarmen Joy Imes, Associate Professor of Old Testament, Prairie College, Three Hills, Alberta 21. Reading the Eye: Optic Metaphorical Agency in Deuteronomic LawA. Rahel Wells, Associate Professor of Biblical Studies, Andrews University5. Epilogue22. Literacy and Postmodern Fallacies Richard S. Hess, Distinguished Professor of Old Testament and Semitic Languages, Denver SeminaryAbstract:23. In Praise of a Venerable Scribe: A Tribute to Alan R. MillardEdwin M. Yamauchi, Professor of History Emeritus, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio[with contributions from Daniel I. Block and Paul J. N. Lawrence]

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

“See That You May Understand”

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Credits

- Figures

- Tables

- Editors’ Preface and Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: “See That You May Understand”

- Chapter 2: Ketiv-Qere

- Chapter 3: Another Inscribed Arrowhead in the British Museum

- Chapter 4: Earliest Literary Allusions to Homer and the Pentateuch from Ischia in Italy and Jerusalem

- Chapter 5: The Etymology of Hebrew lōg and the Identity of Shavsha the Scribe

- Chapter 6: The Writing/Reading/Hearing of the Stone Tablet Covenant in the Light of the Writing/Reading/Hearing of the Silver Tablet Treaty

- Chapter 7: For Whose Eyes?

- Chapter 8: Write That They May Judge?

- Chapter 9: Samuel as Scribal Prophet in 1 Samuel 10:25 and 1 Samuel 1–15

- Chapter 10: Running and Reading: A Reexamination of Habakkuk 2:2c

- Cahpter 11: The History and Pre-History of the Hebrew Language in the West Semitic Literary Tradition

- Chapter 12: Divine Action in the Hebrew Bible

- Chapter 13: Encoding and Decoding Culture

- Chapter 14: No Books, No Authors

- Chapter 15: The Discovery of the Book of the Law in 2 Kings 22:8–10 in the Light of the Literary Renaissance of the Eighth to Seventh Centuries in the Ancient Near East

- Chapter 16: “Read this Torah” (Deuteronomy 31:11)

- Chapter 17: What Is a “Messianic Text”?

- Chapter 18: Joshua 24 and Psalm 81 as Intertexts

- Chapter 19: Belonging to YHWH

- Chapter 20: Reading the Eye

- Chapter 21: Literacy and Postmodern Fallacies

- Chapter 22: In Praise of a Venerable Scribe

- Bibliography