- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

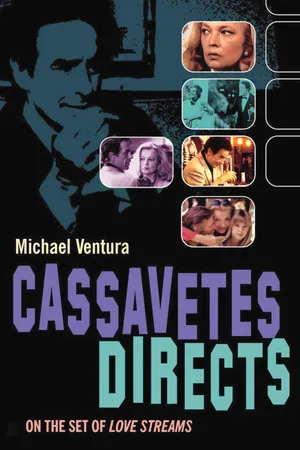

In 1983 visionary director John Cassavetes asked journalist Michael Ventura to write a unique film study—an on-set diary of the making of his film

Love Streams. Cassavetes laid out his expectations. He wanted "a daring book, a tough book". In Ventura's words, "All I had to do for 'daring' and 'tough' was transcribe this man's audacity day by day." Full of insight into not only the filmmaker but his actors and his Hollywood peers, the resulting book describes the creation of

Love Streams shot by shot, crisis by crisis. During production, the director learned that he was seriously ill, that this film might, as it tragically turned out, be his last. Starring alongside actress and wife Gena Rowlands, Cassavetes shot in sequence, reconceiving and revising his film almost nightly, in order that

Love Streams could stand as his final statement. Both an intimate portrait of the man and an insight into his unique filmmaking philosophy, this important text for all movie lovers and film historians documents a heroic moment in the life of a great artist.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cassavetes Directs by Michael Ventura in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 1 – We find out what we can do, we take chances

It’s the morning after. Robert Harmon’s unconscious, in bed (clothed) with two girls – one in a nightgown, the other in pajamas. A girl in a white pants-suit runs in looking for her shoes. We follow her downstairs, where she sees a car pull up in the driveway. She calls upstairs on the house intercom. The phone awakens a groggy girl beside Harmon. She wakes him to report a car has arrived, and there’s a woman at the door with a boy who’s holding a bouquet of flowers. Harmon (suddenly dressed freshly) goes to the door. The woman is his ex-wife Agnes (Michelle Conway). The boy is his son Albie (Jakob Shaw, grandson of Sam Shaw). Robert Harmon hasn’t seen Albie since the day he was born.

Agnes wants four weeks back child support. Harmon writes the check without protest. But that’s not what Agnes really wants. She wants to leave Albie with Harmon overnight. The reason is mysterious – in one line is suggested a seamy sort of life: “My husband and I have a chance to raise some money at someone’s big house, and they don’t want children.” Hesitantly, Harmon accepts. Her tone is wheedling, his is brusque. He has no smile for his son. All the while the boy stares at him with pathetic eagerness and fear, holding flowers.

This simple action will be shot with 12 set-ups. (The rule of thumb on a studio picture is 1 hour per camera set-up. John shoots sometimes much faster than that, sometimes much slower.)

The day begins in the bedroom again, with Cassavetes and two young actresses, in costume, sprawled in bed. While the crew sets up, John and the girls lie there, cuddling, talking, even falling half-asleep. Another actress crawls in with them – she won’t be in the scene, but she wants to cuddle too. The blonde holds John’s hand. Eddie Donno is drawn to them, he stands near, a casual hand on the blonde’s shoulder. Everyone’s kind of dreamy. A most unlikely tableaux! John softly says, in the delivery of a 30s movie, “I could take you girls anywhere, we could go to foreign lands, we’ll get to say to each other, ‘Where were you, I couldn’t sleep.’” Then he cackles, “I can’t believe that we’re all in clothes!”

Mike Stein comes in with make-up. John doesn’t want to get out of bed.

“You wanna stay there?” Stein asks.

“I do, Michael.”

So Stein joins the tableaux, climbing in bed amongst John and the actresses to apply their make-up.

Earlier John told me that he got the idea of Robert Harmon and the girls clothed in bed when the actress in the shower-scene wanted to wear her bathing suit: clothes-in-bed was precisely the right touch to reveal Harmon’s sexual state, or lack of it, and protect these scenes from being vulgar. (“Vulgar” is his word).

The scene is shot efficiently, with exactly the “sloppy” quality John was looking for yesterday. The gal comes in looking for her shoes, John and the gals stir a bit in bed and slur a bit about being disturbed. The shoe-gal leaves. Then the intercom phone rings, one of the gals gropes for it, and, as he wanted yesterday, “the confusion of the action is the scene.”

Still, John is concerned about the adrift, groping quality of these last few days. While the next shot sets up he tells me, “This picture, I don’t know how, has gotten stuck in – I don’t know – the beauty of ordinariness. Camera work. We’ve got to get into the picture now, or we’re not going to have a movie.” He turns to walk away, then turns back and says, to himself more than to me, “I don’t have enough courage.” (Some men get their courage by never thinking they have enough.) Then John says to me, “If I can’t wake up my own self I can’t expect to wake everybody else up.”

What wakes up John Cassavetes the director – perhaps because it shocks Robert Harmon the character, and throws him off his game – is the arrival of little Albie, an eight-year-old seeing his father for the first time. The world of women is all too well known to Robert Harmon; the boy is the arrival of the unknown. Now Harmon must deal with male energy, for one thing, which it seems he’s structured his life to avoid. The boy is what he made, and is a version of what he once was, and he won’t be able to control or win over the boy with money or will power. For the first time in probably a long time, life is testing Robert Harmon. Can he face this?

The day’s set-ups are intricate: angles, through the windows, of the girls noticing ex-wife Agnes’ car drive up; Agnes and Albie getting out of the car, hesitating, afraid – again, seen through windows. Then Harmon, Agnes, and Albie at the front door. Close-ups of Agnes and of Harmon as they speak. The door is half-open, and there is a long shot on Albie from inside the house – a slow zoom, slowly ending in a close-up of the boy as he listens to his mother and father, never looking at his mother, staring at his father. In that shot we hear Agnes and Robert, but the half-closed door conceals them from our view. We’re only on the boy.

No improvised dialogue today. The script is precise in its awkwardness. Harmon is cold to the point of cruelty. Agnes is anxious, needy, pretty in a haggard way, out of control in a tight way, sputtering with the energy of an intelligence gone unused and now unsalvageable.

There is one improvised line, but it won’t be used in the film; as he will often do, Cassavetes speaks the line as a way to direct while in the midst of the scene. On a close-up, Michelle Conway is speaking Agnes’ dialogue. The scene has been shot from several angles now and Agnes’ lines are coming too glibly for John’s ear. John, with no warning, his voice dripping with sarcasm, interrupts her to say, “You’re such a beautiful kid, so sincere, money isn’t important to you, right? What a cunt you are.”

Michelle’s expression is stripped raw, she hesitates, stumbles on with her lines – just what John wants. John told me the night before, “I don’t direct. I set up situations, and either they work or they don’t.”

Concentrated, efficient shooting all day and everybody’s into it. At dailies later, even Al Ruban is talky, enthusiastic – the only time he’ll show those qualities in my presence. I respected him instantly, but we won’t warm to each other and he’ll refuse to be interviewed. (I’ll often ask myself, “How come John Cassavetes doesn’t intimidate me and Al Ruban does?”) Ruban’s brought his camera crew to tonight’s dailies – to give them confidence, I believe. He praises their work. In particular, Ruban enjoys one shot from yesterday’s effort: Robert Harmon walking out of the dark with his shirt half-buttoned, John’s swollen belly catching the light. Al tells his team, “We find out what we can do, we take chances – that shot of him coming out of the dark, that was enough for me, that was beautiful.”

After dailies, as we’re walking to our cars, Ruban does me the rare honor of addressing me. He says of Cassavetes, “He’s a man of great courage. He’s not afraid to fall on his face.”

“Gena asked Al yesterday,” John says, “she asked him, ‘What did you think of this stuff, are you excited?’ He said, ‘If I get happy, the penalties for being overly enthusiastic, the depression at the failure of it is so strong that I can’t afford to commit myself.’ I thought –” John laughs suddenly “ – I thought it’s wonderful to see this guy, who’s most of the time quite stonefaced and strong, suffering so terribly on the work, you know? Because he’s such a charming guy when he’s not working. And quite charming when he is working, but totally non-committal. And very sensible.”

Everything shot today will be used. Edited, of course, but – from the first draft to the final cut – these scenes will appear as conceived, without restructuring their original intent or placement. Interestingly, except for two close-ups of Harmon and one of Agnes that last for barely a second each on-screen, the doorway scene will consist entirely of the zoom onto Jakob Shaw’s heartbreaking expression, seen from inside the house through the half-opened door – we will only hear Harmon and Agnes. Cassavetes’ decides that in this scene the boy is most important.

THURSDAY, JUNE 2 – Don’t cry on my set

“Wave goodbye to your mother” are the first words Robert Harmon has ever spoken to his son. Alone together, father and son don’t know what to do or say. As they go into the house Harmon lightly, tentatively, pats Albie’s hair – one pat. Harmon is stiff, his expression stern. Albie is plaintively and silently begging to be loved. When they enter the house, Albie compulsively hugs his father. Harmon doesn’t hug him back, just pats the boy’s shoulder – once – and says, “Okay” as though saying, “That’s enough.”

He introduces Albie to his assistant Charlene and her daughter Renee. Renee is jealous of the newcomer. The camera will be on Albie, clearly going through hell, biting his lip. Next Harmon introduces Albie to the bevy of gorgeous young women upstairs. The gals make a big fuss, pawing Albie, oooing and ahhhing. Albie bolts. Runs down the stairs, out of the house, down the winding driveway. Harmon just stands at the window, angry, watching his son run. The gals bound off to chase Albie, one telling Harmon that he’s got to get the boy, “He’s your son, for crissake.” Suddenly Harmon runs downstairs, gets into his convertible, drives too fast down the driveway, narrowly missing some of the women. Harmon catches up to Albie down the street, forces him into the car, takes him back to the house. Albie is both crying and trying not to cry, and he keeps calling his father “Mr. Harmon.”

“Don’t call me ‘Mr. Harmon’!” Robert commands fiercely. “That’s insulting, and I know you know it.”

“I hate you!”

“That’s because I’m your father.”

Last night John talked with me into the wee hours – while Gena was expressively annoyed at his drinking and cursing. He drank. I didn’t. I’m exhausted. He’s not. He can’t afford to be, he’s scheduled 20 set-ups today. And they’ll get done.

Almost all will involve the boy.

Jakob Shaw has known John all his young life. Sam Shaw, John’s mentor and collaborator, is Jakob’s grandfather. Larry, the film’s still photographer, is his father. Larry Shaw has groomed his son to be an athlete ever since the boy could walk, it seems, and on any pretext Larry and Sam speak proudly of how fast Jakob can run, how great he is at soccer, at wrestling, at anything sportive. Cassavetes and his friends are sports fanatics with a seemingly inexhaustible statistical knowledge of every man on every team of every sport – Jakob’s athletics are important to the men in his life, so he is no stranger to high expectations and to staking his young honor on competition and endurance.

“Don’t cry on my set,” John tells him. John’s eyes glint with humor, but it’s a humor that means business.

“I’m not cryin’.”

“Don’t.”

“I’m not.”

Jakob knows this style of humor well. He doesn’t sm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Table of Contents

- Introduction:

- THURSDAY, MARCH 17, 1983 – Trying to get it

- THURSDAY, MARCH 24 – No more room on the napkin

- APRIL-MAY – Friends of Sam

- WEDNESDAY, MAY 25 – I don’t understand where all this light is coming from

- THURSDAY, MAY 26 – We can’t tell them the answer unless they ask the question

- FRIDAY, MAY 27 – People use that language when they’re in trouble

- TUESDAY, MAY 31 – The confusion of the action is the scene

- WEDNESDAY, JUNE 1 – We find out what we can do, we take chances

- THURSDAY, JUNE 2 – Don’t cry on my set

- FRIDAY, JUNE 3 – It’s harder to do slow

- MONDAY, JUNE 6 – About your life

- TUESDAY, JUNE 7 – A cinema of alcohol

- WEDNESDAY, JUNE 8 – Gena’s first day

- THURSDAY, JUNE 9 – If I die

- FRIDAY, JUNE 10 – Love is a stream

- MONDAY, JUNE 13 – He wants you to do it in your way

- TUESDAY, JUNE 14 – Nothing to hide behind

- WEDNESDAY, JUNE 15 – Cuisine of Tony the Ant

- THURSDAY, JUNE 16 – Keep it a secret, ok?

- FRIDAY, JUNE 17 – You stink

- MONDAY, JUNE 20 – The worst I’ve seen him blow

- TUESDAY, JUNE 21 – All that jazz

- WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22 – A movie, not a moment

- THURSDAY, June 23 – My dinner with Cassavetes

- FRIDAY, JUNE 24 – You can’t hide anything

- MONDAY, JUNE 27 – It’s a dream

- TUESDAY, JUNE 28 – I don’t dance unless I have a drink

- WEDNESDAY, JUNE 29 – Let him do it

- THURSDAY, JUNE 30 – A quick yes

- FRIDAY, JULY 1 – Not afraid of being bad

- TUESDAY, JULY 5 – No man’s man

- WEDNESDAY, JULY 6 – Building a house

- THURSDAY, JULY 7 – I love stupidity

- FRIDAY, JULY 8 – Hours of beginnings

- MONDAY, JULY 11 – Did I kiss you off a little abruptly?

- TUESDAY, JULY 12 – Where were you?

- WEDNESDAY, JULY 13 – What are you doing behind the camera?

- THURSDAY, JULY 14 – Speak, Jumbo, speak!

- FRIDAY, JULY 15 – Limbo

- MONDAY, JULY 18 – It’s like music

- TUESDAY, JULY 19 – Fifteen hours a day isn’t enough

- WEDNESDAY, JULY 20 – If it was easy anybody could do it

- FAST FORWARD: MONTHS LATER – The best story

- THURSDAY, JULY 21 – Hating okra

- FRIDAY, JULY 22 – Every line in your life

- MONDAY, JULY 25 – That’s very dangerous

- TUESDAY AFTERNOON TO SATURDAY DAWN, JULY 26–30 – Double sixes

- MONDAY, AUGUST 1 – The fuckin’ end of the world

- TUESDAY, AUGUST 2 – I didn’t make it for you anyway

- WEDNESDAY-THURSDAY, AUGUST 10–11 – That is a wrap

- I’M GONNA HAVE MY OWN LIFE

- Illustrations

- Copyright