- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

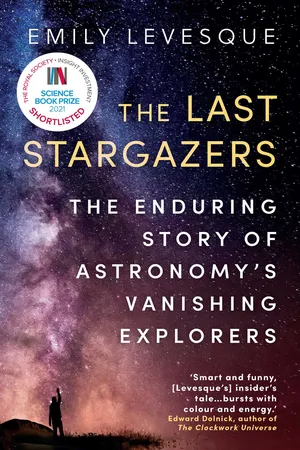

About this book

Discover the story of the people who see beyond the stars…

SHORTLISTED FOR THE ROYAL SOCIETY SCIENCE BOOK PRIZE 2021

FINALIST FOR THE PEN/E.O. WILSON LITERARY SCIENCE WRITING AWARD

AN AMAZON BEST BOOK OF 2020

To be an astronomer is to journey to some of the most inaccessible parts of the globe, braving mountain passes, sub-zero temperatures, and hostile flora and fauna.

Not to mention the stress of handling equipment worth millions. It is a life of unique delights and absurdities … and one that may be drawing to a close. Since Galileo first pointed his telescope at the heavens, astronomy has stood as a fount of human creativity and discovery, but soon it will be the robots gazing at the sky while we are left to sift through the data.

In The Last Stargazers, Emily Levesque reveals the hidden world of the professional astronomer. She celebrates an era of ingenuity and curiosity, and asks us to think twice before we cast aside our sense of wonder at the universe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Last Stargazers by Emily Levesque in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Astronomy & Astrophysics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

FIRST LIGHT

TUCSON, ARIZONA

May 2004

I got my first glimpse of a telescope—a real, large, world-class-observatory telescope—on the road heading west from Tucson. I had just finished my sophomore year at MIT, flying to Arizona straight from my final exams in quantum physics and thermodynamics, and was picked up at the Tucson airport by Phil Massey, an astronomer with gray mad-scientist curls, black-rimmed glasses, and a wide grin. My research adviser for the next ten weeks, he was driving me to Kitt Peak National Observatory, deep in the Sonoran Desert, where we’d be spending five nights observing at one of the telescopes as a kickoff to my summer project. It would be my very first visit to a professional observatory.

I had learned from our email exchanges that I would be studying red supergiants. Red supergiants are massive stars with at least eight times as much mass as our own sun. Because of their large masses, they’ve sped through their stellar lives at breakneck speed, taking a mere ten million years to transform from their newborn state—brilliant blue-hot stars freshly formed out of gas and dust—to their current state, blazing deep red like a dying ember and swelling up to many times their original size in a last-ditch effort to stay stable and alive. Death for these stars most likely means a violent interior collapse followed by a rebound explosion known as a supernova, one of the most luminous and energetic phenomena in the universe and the process by which black holes are sometimes formed.

Phil and I had met just once before, briefly, the previous January, and he’d chosen me as his summer student based on a presentation he’d seen me give on my first foray into astronomy research. When we’d first started discussing plans for the summer, Phil had offered me a choice of two projects, literally red or blue: the red dying stars or the blue newborn ones. I didn’t know a great deal about either, but I thought black holes were fascinating, and since the dying stars seemed fractionally closer to that point, I opted for red. At Kitt Peak, Phil and I would be observing about a hundred red supergiants in our own galaxy, the Milky Way. I’d then spend the rest of the summer working with the resulting data, trying to measure the stars’ temperatures and contribute a tiny piece to the ongoing astronomy-wide puzzle of exactly how these stars evolved and died.

Phil and I chatted and got to know each other on the drive, but I was also gawking out the window at the southern Arizona desert. The baking summer heat and sunlight were stunning, a world away from the muggy green spring I had left behind in Massachusetts, and I took in the orange-brown dirt and stretches of saguaro cactus and beaming blue sky. Phil pointed out the tiny white silhouette and pair of contrails from a high-altitude jet and mentioned that experienced astronomers can gauge the quality of the sky they’ll be observing that night based on how long the contrails are. If they’re long and fluffy, there’s a lot of moisture in the atmosphere to stir up and interfere with the starlight, while if they’re short—just a little tuft trailing behind the plane—we would be in for a crisp and clear night. The jet we were watching had a short tail.

Phil knew the drive to the observatory by heart and told me where to look at the exact moment when Kitt Peak’s four-meter telescope first popped into view. The white dome, eighteen stories tall, glinted in the pounding desert sun. The telescope inside has made groundbreaking observations of everything from nearby stars to impossibly distant galaxies in the decades since it achieved “first light”—the moment when the completed telescope took its first look at the night sky—in 1973.

The vast majority of modern-day telescopes use mirrors to collect light from the stars, and the most fundamental property of these telescopes is the mirror’s size. A larger mirror means that when we point the telescope at an object, a bigger area is available to collect light from the object. (It’s the same principle behind why your pupils dilate in a dark room.) The distance from one side of a mirror to the other—its diameter—also dictates how sharp of an image the telescope can produce, like using a telephoto lens to get a clear photo of something small and far away. For well over a century, major strides in astronomy have revolved around the progression toward bigger and bigger mirrors, with their diameters dictating a telescope’s fundamental ability to see farther into space. As a result, mirror size has become the defining characteristic of a telescope, to the point where it’s sometimes entwined in the telescope’s name or even defines the name entirely. At Kitt Peak, the flagship telescope is widely referred to as “the four-meter.”

Eventually, we peeled off Route 86—already an incredibly barren and empty stretch of highway—and started winding our way up a meandering mountain road. At first, there was very little sign that we were going anywhere but deeper into the desert: long stretches of pavement, some switchbacks, and minimal signs of any life at all beyond the cacti. The only clue that we were heading to an observatory was the occasional curve of a white dome peeking out from between the hills. Later on, we started getting a few hints that we were not on just any mountain. As we neared the summit, signs started appearing, imploring nighttime drivers not to use high beams and eventually not to use any headlights at all in an effort to preserve the mountain’s darkness.

Today’s best observatories are built in the high, dry, remote places of the world. High altitudes give us a slightly thinner atmosphere and less turbulence in the air between the summit and the stars. Deserts mean air devoid of water vapor and moisture, good for weather and for image quality. The reasoning behind the remote locales is a bit more obvious: the farther we are from the rest of the world, the darker the skies (although even the darkest parts of the planet are fighting a constant battle against encroaching light pollution).

Kitt Peak lies near the southern border of the United States, less than thirty miles from the Mexican border. The mountain itself is all brown rock and stubby trees, indistinguishable from the desert around it but for two things: the white domes hunkered like sleeping giants across the long summit ridge and the invisible but very real perfection of the air passing over the summit. The land around the observatory largely belongs to the Tohono O’odham Nation. A prominent rock formation in the distance, shaped surprisingly like a telescope dome, is known by them as Baboquivari and is, in their cosmology, the center of the universe.

As our car climbed, I found myself wondering: what’s a professional observatory going to be like? I had a mental picture of a big behemoth of a telescope like the one we’d spotted from the road, perched white and alone on some stark rock outcropping of a mountain ridge, but that was about it. I hadn’t much thought about details like where we’d sleep (during the day? would we sleep?), what we’d eat (should I have brought some snacks?), or any of the other logistics. I figured it would all sort itself out and focused instead on drinking in our surroundings as we neared the summit.

TAUNTON, MASSACHUSETTS

1986

Not quite knowing what was coming was not a new sensation. I’d long since come to terms with the idea of optimistically ploughing forward with “I want to be an astronomer!” as my guiding plan.

I’d been enraptured by space for as long as I could remember, but the original spark could be traced back to early 1986, when Halley’s Comet made its most recent close flyby of the earth. My parents and older brother and I lived in a suburb of Taunton, Massachusetts. A blue-collar southern New England city with industrial roots, it nevertheless gave way to forested streets and ponds and cranberry bogs once you made it a few highway exits out of town—dark enough for stargazing.

Neither of my parents were scientists by training. Before I was born, they’d both earned teaching degrees, with a focus in special education. My mom worked as a speech therapist but eventually went back to school for a graduate degree in library science and moved up through the library positions of the Taunton school system. My dad had studied teaching but worked as an independent truck driver for years while becoming a self-taught computer expert, and by the time I was born, he was working at an insurance company as an IT specialist.

Still, both of them were scientists by nature, fundamentally curious about the world around them and constantly eager to learn as much as they could about whatever corner of it might catch their attention. My dad had taken an astronomy class as an elective in college at Northeastern, which made enough of an impression for him to take it up as an interest and pass the enthusiasm along to my mom.

In keeping with their lifelong habits, once my parents got into something, they were into it, full bore. When that something was astronomy, my dad scraped up funds to buy a backyard Celestron C8, a squat orange cylinder with an eight-inch mirror, and built his own table to mount it on along with some added shelving to store eyepieces, equipment, and a copy of Norton’s Star Atlas. The flames were further fanned by Carl Sagan’s Cosmos television series premiering in 1980, which prompted my librarian mom to stock up on his books. By the time I was born in 1984, astronomy was a background buzz in our house in the same vein as gardening, woodworking, birds, and classical music. My parents were determined to give my brother and me a rich and varied set of potential interests to explore.

Still, the real catalyst sparking my interest in astronomy was my brother, Ben, almost ten years my senior. I’m fairly convinced that when two siblings are this far apart in age, hero worship is just part of the package. Growing up, Ben was always the first and foremost arbiter of all things cool in my eyes, and he was endlessly patient with me rather than annoyed by a tiny tagalong. Ben played the violin, and therefore I asked to play the violin. Ben did science fair projects, so I started fashioning nonsensical “experiments” out of whatever toys or household items I could get my hands on. I even wanted braces because Ben had them (an opinion that was reversed rapidly once I was the one in the orthodontist’s chair).

In February 1986, I was eighteen months old, and Ben was eleven, studying Halley’s Comet for a school project. These sorts of projects always became full-family endeavors, so all four of us tromped out into the backyard one cold winter night, armed with our eight-inch telescope and its homemade table, to get a glimpse of this once-in-a-lifetime comet flyby (it’s next due back in 2061). According to my parents, I was brought out to get a brief look with the worry that I might be a typical fussy toddler, scared of the dark and eager to get back inside. Instead, I was entranced: gaping up at the sky, staring through the telescope (in retrospect, I’m amazed that a not-yet-two-year-old could look through an eyepiece, but they swear I managed it), and refusing to go back inside as long as Ben was still observing.

The love of astronomy stuck in a way that my love of braces didn’t. I was an early and voracious reader, and a few years after Halley’s Comet, I was learning about star clusters and black holes and the speed of light thanks to Geoffrey T. Williams’s Planetron books, which chronicle the adventures of a little boy with a toy that transforms into a magical spaceship and sweeps him off to explore the heavens. I have a strong memory of being five, reading about how fast the speed of light was, and repeatedly flicking the light switch on and off in my room to convince myself that yep, once I flipped it on, the light arrived pretty much instantly. That seemed pretty fast to me.

Later, I inhaled every astronomy book I could get my hands on, watched Mr. Wizard and Bill Nye on TV, and went to every movie about scientists and space that came along. I remember particularly enjoying the movie Twister because it gave me an encouraging look at what scientists themselves might actually be like. The fictional tornado researchers on screen were doing cool and exciting research and having fun along the way, and the main character was a woman who rolled around in the mud and was obsessed with science but still managed to end the movie with a great kiss (a combination I’d already been warned might not be tenable in the long run thanks to plenty of other movies featuring women who Had to Choose between Careers and Men).

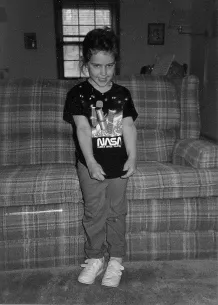

Age six, sporting my beloved new Hubble Space Telescope T-shirt shortly after its 1990 launch. Credit: Henri Levesque.

My parents did what they could to encourage my interest in space, but opportunities to explore a career in astronomy aren’t exactly found on every street corner. None of us even knew a professional scientist, let alone an astronomer, and while my entire extended family was filled with kind and bright and enthusiastic people, nobody had a PhD or knew much about what this sort of job entailed. All four of my grandparents had left school at young ages, despite being uniformly strong and passionate students, to work in local factories and contribute income to their families. My maternal grandmother in particular had been devastated by this and wept the day she left school; she later returned to complete a high school degree alongside my grandfather, Pépère, and went on to get a practical nursing degree while raising five kids, with Pépère working at the big silver factory in town. My parents and some of my aunts and uncles had all been first-generation college students, drinking in as much education as they could but ultimately getting practical degrees that would lead to good jobs: engineering, actuarial science, teaching. It was a big, loud, and exceedingly loving family, buoyed by an immense amount of collective curiosity and a love of learning for learning’s sake, but nobody had a road map at hand for how to get started on a career in something as intangible and fanciful as astronomy.

I did get to chat with a professional astronomer once during my childhood. Our house was a twenty-minute drive away from Wheaton College, a tiny but excellent liberal arts college. When I was seven, my parents took me to a public stargazing night at the campus rooftop observatory, and I quickly informed the professor running the event that I wanted to be an astronomer. He bent down to my height, looked me right in the eye, and said, “Take as much mathematics as you can.” I stared seriously back at him and responded, “Okay.” From then on, maths became my focal subject in school. I skipped one grade of maths, then another, falling into complex bus arrangements for a few years to get me between the high school where I took first year geometry and the middle school where I took seventh grade everything else.

In July 1994, a flurry of astronomical excitement hit the news when word got out that the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet was on a collision course with Jupiter. As the strike approached, speculation both inside and outside the astronomy community was focused around what would happen to Jupiter after being hit by a comet. Would we see any signs of the impact? The fabulous new Hubble Space Telescope was scheduled to observe it, but nobody was quite sure what they would see.

After the impact, the news came quickly that the view exceeded all expectations. The comet strike had left what looked like a spray of stark dark-brown bruises across Jupiter’s lower flank. I remember a clip being shown over and over of a group of astronomers huddled around a few computer monitors at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, grinning and gasping with excitement at what they could see. At the heart of the group, a bespectacled young woman named Heidi Hammel sat front and center, gleefully celebrating with her companions as spectacular images of Jupiter came rolling in. My dad and I brought the backyard telescope outside soon after and spotted the impact scars on Jupiter with our own eyes, but that glimpse of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: First Light

- Chapter Two: Prime Focus

- Chapter Three: Has Anybody Seen the Condors?

- Chapter Four: Hours Lost: Six. Reason: Volcano.

- Chapter Five: The Harm from the Bullets Was Extraordinarily Small

- Chapter Six: A Mountain of One’s Own

- Chapter Seven: Hayrides and Hurricanes

- Chapter Eight: Flying with the Stratonauts

- Chapter Nine: Three Seconds in Argentina

- Chapter Ten: Test Mass

- Chapter Eleven: Target of Opportunity

- Chapter Twelve: The Supernova in Your Inbox

- Chapter Thirteen: Synoptic Future

- Reading Group Guide

- Interviews

- Notes

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright