![]()

TWO

TEMPLARS,

ILLUMINATI AND

FREEMASONS

THE SECRET SEAT OF POWER

WHO ARE THE MOST DANGEROUS MEMBERS OF THE VARIOUS secret societies skulking the earth, people with power to change our lives and direct the course of history? According to sources claiming inner knowledge of the group's true purpose, they are Freemasons. Masonic conspirators choose international leaders, launch wars, control currencies and infiltrate society, among other applications of their hidden powers, or so the tales propose. When anyone questions this premise, conspiracy theorists trot out an impressive array of proof, beginning with a recital of influential men through history who were undeniably associated with Masonry, including many signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Who holds higher positions in the American pantheon of heroes and great thinkers than Benjamin Franklin, George Washington and Andrew Jackson? All were Freemasons. In fact, at least twenty-five U.S. presidents and vice-presidents have been active and enthusiastic supporters of Masonry. Two of them—Harry Truman and Gerald Ford—could boast 33rd Degree status, the highest level of recognition within the organization.

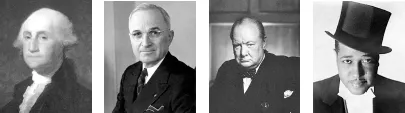

Masons dominated Western politics and cultures for years. Among their members were U.S. presidents George Washington and Harry S. Truman, British prime minister Winston Churchill, and the elegant Duke Ellington.

It is a remarkable achievement, this elevation of a private club with secret rituals into an incubator of leaders, visionaries and intellectuals. On the face of it, the Masons appear to inspire men of exceptional talent far beyond that of any other organization ranging from the Boy Scouts to Rhodes scholars. What is it about their values and systems that breeds such overachievers?

To a few fanatic historians—almost all of them Masons—at the root of their achievements is a historic and inspirational link with the Knights Templar, who began as Defenders of the Christian Faith, became the bankers of medieval Europe, and succumbed to the machinations of a greedy king and a complicitous pope.

Once acclaimed and admired for chivalrous deeds and good works on behalf of Christianity, the Knights Templar safeguarded pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land and battled Islamic armies for control of Jerusalem. Genuine knights in an era when that title brought respect and admiration, they obeyed rules of chivalry and asceticism, dedicating their lives to the glory of God and the protection of Christian pilgrims.

That was the admirable side of the society. The darker side hid rumors of associations between Templars and the Assassins, the replacement of Templar moral values with outright greed, a decline in commendable character traits and the pursuit of various obscene and blasphemous practices. These attributes are not a model for any high-profile organization seeking respect, let alone one that prides itself on providing world leaders and community benefits. But dark complexity and suspicion provided the necessary intrigue and color for a later group whose original objective was to protect the secrets of tradesmen. Along the way, the Templars’ spiritual leader managed to be compared to, and perhaps even mistaken for, Christ himself.

In their early years, Knights Templar were identified with chastity, piety and bravery. Later, their reputation grew less admirable.

The Templars were a product of the Crusades. And the Crusades, contrary to popular belief, were the result not of chivalrous intent or even a dedication to the Christian faith, but of feudalist obligation.

Historians, as is their manner, vacillate as much about the definition of feudalism as they do about its structure, and a few now reject the notion of a “feudalistic age.” Whatever title is hung upon it, Europeans living during the period between ad 800 and 1300 experienced a way of life that bridged inchoate barbarianism and the roots of democracy. During this time, kings may have claimed wide authority over lands we now know as France, Germany, Britain, but the countryside was effectively ruled not by monarchs but by individual lords and barons. Dominating the lands encompassed by their estates, the lords dispensed justice, levied taxes and tolls, minted their own currency, and demanded military service from citizens occupying their lands. Most lords, in fact, could field larger armies than could the king, who was often a figurehead ruler.

The social structure was many layered and clearly defined. Serfs represented the lowest level, performing basic labor and having no claim to any wealth they created. Vassals worked the land on behalf of the lord; knights, whose primary qualities included sufficient funds to own both a horse and armor, performed services on behalf of the lords; and the clergy administered spiritual assistance as required. Lords, in turn, were considered vassals to more powerful rulers, and all were formally considered vassals to the king.

Feudal loyalty flowed in two directions. The citizens made an oath of loyalty to the lord, paid taxes imposed by him, and attended the court when summoned. The lord's obligation included protecting the vassals from intruders, an act that was admittedly as much in the lord's interests as in the vassals’.

Out of this linear arrangement, subjected to the influence of Christianity, came the concept of chivalry. Vassals and knights, heeding the rights and property of their feudal lord, elevated the notion through terms such as “proud submission” and “dignified obedience” inspired, perhaps, by Biblical tales of Christ's actions. Phrased in this manner, behavior that appears to mirror a master–slave relationship was spun into something more reputable and uplifting. As contradictory as it may sound, individuals could elevate their status by lowering their position on behalf of some splendid goal. Popular literature suggests that the incentive for chivalrous behavior was romantic interest in an elegant lady who had stolen the knight's heart, and to whom he pledged eternal reverence. In reality, a knight's “proud submission” was made either to God or to the lord who controlled the knight's destiny. The romantic aspect of chivalrous behavior, glorifying womanhood in a manner that combined worship of the Virgin with suppressed sexual desire, remains an inspirational source for much fiction but was basically a by-product of a deeper motivation.

Chivalric demands were rigid. Obligations were expected to be fulfilled, and vassals and knights accepted a sacred duty to defend by arms the honor and property of the class above themselves. Since the pyramid structure of medieval society set Christ at the apex, lords, knights and vassals alike were equally obligated to defend His rights and honor.

With feudalism solidly established throughout Europe, lords and knights, accompanied by a retinue of servants, began the practice of making pilgrimages to Jerusalem as a means of expressing their Christian faith. Reviving a concept dating back to early Greeks, who trekked to Delphi in search of wisdom, European Christians began setting off on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, first in honor of Christ, later as a means of cleansing their sins, and later still in response to direct instructions from the pope.

Prominent early pilgrims in search of spotless souls included Frotmond of Brittany, who murdered his uncle and younger brother; and Fulk de Nerra, Count of Anjou, who burned his wife alive, which was evidence of serious marital discord and abuse even in those tumultuous pre-feminist times. Both men sought forgiveness with a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and both achieved success, albeit in contrasting measure.

After years spent wandering the shores of the Red Sea and searching the mountains of Armenia for relics of Noah's Ark, Frotmond returned home swaddled in the warmth of forgiveness for murdering his relatives, and passed the remainder of his days in the convent of Redon. For his sins, Fulk de Nerra wandered the streets of Jerusalem accompanied by a retinue of servants who beat him with rods while he repeated the words, “Lord, have mercy on a faithless and perjured Christian, on a sinner wandering far from his home.” His apparent sincerity impressed the Muslims so much that they granted him entry into the room of the Sacred Tomb, normally forbidden to Christians, where he threw himself prostrate upon the bejeweled floor. While wailing for his wretched soul, de Nerra managed to detach and pocket a few precious stones from the site.

The examples set by Frotmond, de Nerra and others had their impact on devout Christians. Around ad 1050, making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land was considered a duty for every able Christian as a means of assuaging guilt and appeasing the wrath of God, and the Church began assigning a pilgrimage as a common means of penance. By 1075, pilgrimage trails had become as well defined and well traveled as trade routes.

The pilgrims’ trek, usually tracing the Adriatic coast before turning overland to Constantinople and across Asia Minor to Antioch, was neither more nor less dangerous than any other journey of similar length. Their established route, however, proved a factor in 1095 when Byzantine emperor Alexius Comnenus pleaded for Pope Urban ii to help in defeating a group of Muslim tribes known as the Seljuk Turks. After seizing Anatolia, the Byzantine Empire's richest province, the Seljuks occupied Antioch, Tripoli and finally Jerusalem. Now, it seemed, they had their eye on Constantinople itself. If the pope could organize an army of dedicated Christians to assist Byzantine troops, Alexius suggested, together they could retake Antioch and restore Jerusalem itself to Christian rule.

The promise of Christian rule over the Holy Land, bolstered by expectations of wealth tapped from the Byzantine emperor's own treasury, was enough to inspire Urban ii to launch the first papacy-sanctioned holy war. Thus, almost two hundred years of horrific slaughter on both sides began with a goal as much mercenary as it was spiritual, and in 1096 the first of nine crusades set off, inspired by Urban's cry Deus vult! (God wills it!)

Deciding to take part in a crusade was a serious decision, even for the most devout of Christians. It meant at least two years of travel across rugged and often hostile country, although later crusades reduced the time by sailing eastward along the Mediterranean from Provence. Seeking food and shelter during the long journey from Europe to Palestine and back, pilgrims and crusaders had to deal with open hostility from both the Muslims and Greek Orthodox administrators. In response Gerard de Martignes established a hospital in Jerusalem to serve as a refuge. Consisting of twelve attached mansions, the facility included gardens and an impressive library. Soon local merchants created an adjoining marketplace to trade with the pilgrims, paying the hospital administrator two pieces of gold for the right to set up stalls.

This was too good for feudal entrepreneurs to ignore. When the flow of pilgrims swelled to an endless flood, a group of Italian traders from the Amalfi region established a second hospital near the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, this one operated by Benedictine monks, with its own profitable marketplace. Soon the second facility began overflowing, promoting the monks to create yet another hospital, dedicating it to St. John the Compassionate.

The men of St. John the Compassionate elevated the concept to a new spiritual status. They devoted their lives to providing safety and comfort for pilgrims by treating their patients as their masters, creating a prototype for every charitable organization that followed them, although none matched their dedication and humility. This practice, of course, reflected the true origins and goals of chivalry, attracting many knights who set aside their military objectives in favor of emulating the most charitable of Christ's teachings. Their military bearing and discipline were never wholly discarded, however. Among those they served, the knights were liberal and compassionate; among themselves, they were rigid and austere. They pledged vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and their dress became a black mantle bearing a simple white cross on the breast. They were called the Sovereign Military Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, known simply as the Hospitaliers.

The two Templars on horseback, as shown on their seal, indicated brotherhood, but later generations spied a sexual reference.

Vows of poverty, chastity and obedience may have suited their obligations to chivalrous behavior (and, they no doubt anticipated, facilitated their entry into heaven), but they did little to protect the Hospitaliers from the dangers of attack by various factions in the Holy Land. With time, the Hospitaliers grew focused almost as much on their military actions in defense of their order as on their acts of benevolence. Most were armed knights, after all, noble of birth and adhering to the high standards of true chivalry.

They were also as human as anyone else, of that era or ours, and when powerful European duchies expressed admiration for the Hospitaliers by awarding them extensive lands in Europe, the members accepted the donations gladly. In addition to this source of income, they assumed the right to claim booty seized from defeated Muslim fighters, and by the time Gerard died in 1118 the Hospitaliers had acquired substantial assets from their patrons, and exceptional independence from Church authority. What began as selfless dedication to the poor, injured and diseased had evolved into an organization more akin to a modern-day service club, whose well-heeled members were at least as interested in fraternal association and public status as they were in helping their neighbors.

The Hospitaliers may have been capable military men, but their raison d’être continued to be public service. Battling Muslims while fulfilling their obligations was proving a distraction from their primary goal, and others were needed to direct as much energy into fighting the enemy as the Hospitaliers were investing in caring for Christians.

It may be cynical to imply that the wealth accrued by the Hospitaliers as a result of their charitable services inspired their more celebrated brethren, but history suggests it played a role. In any case, a new society was formed within ten years of Gerard's death. Comprised originally of nine knights led by Hugh de Payens, the followers claimed the same ascetic and pious characteristics that distinguished the original Hospitaliers. This new group, however, focused on the hazards faced by pilgrims and Crusaders—by now the distinction was growing blurred and almost meaningless—during their trek to the Holy Land and their stay in Jerusalem.

The hazards arose from multiple threats. Egyptians and Turks resented passage and intrusion through their countries, Islamic residents of Jerusalem objected to the pilgrims’ presence, nomadic Arab tribes attacked and robbed the travelers, and Syrian Christians expressed hostility towards the foreigners.

Much of the group's early reputation for humility and valor was rooted in de Payens’ personality, described as “sweet-tempered, totally dedicated, and ruthless on behalf of the faith.” To a modern sensibility, the concept of being sweet-tempered and ruthless may appear contradictory, but to medieval observers they were perfectly compatible. A battle-hardened veteran of the First Crusade, de Payens took delight in recounting the number of Muslims he had slain without, apparently, souring his day-to-day charitable mood. And why should he? The even more pious Bernard of Clairvaux had declared that the killing of Muslims was not homicide but malicide, the killing of evil. Thousands of dead Muslims in the Holy Land may have begged to differ, but their opinions were rarely sought.

So de Payens, single-minded to the exclusion of everything except the worship of God and the slaughter of Muslims, gathered men around him who committed themselves to protecting pilgrims from danger in the same manner that Gerard's Hospitaliers were healing and feeding them. The new group, de Payens announced, would combine the qualities of ascetic monks and valiant warriors, living a life of chastity and piety, and employing their swords in the service of Christianity. To aid them in achieving this somewhat contradict...