![]()

1

FROM KABUL TO NEW YORK

I never liked mirrors. The elevator doors opened, and I couldn’t escape seeing my own reflection in front of me; it was impossible to avoid.

Fifty-fourth floor.

My eyes met those of a man without a beard, of a woman without charm. Large stature, powerful jaw line. Me. A pointed nose, thin lips. I moved forward, smiling to reveal my false gold tooth. Its original luster was well tarnished. I needed to change it. My eyes. I never really knew the color of them. Neither blue, nor green, nor brown. Zarze, as it is called in the language of my people, Pashto.

Forty-seventh floor.

I stepped back. Age had altered my strength as a man. My lumberjack arms remained, my shepherd legs, the stoutness of a healthy Afghan. What would they think of me, down below? I was intimidated. This rich hotel, this conference filled with important people. It was said that Michelle and Hillary would be there. Mrs. Obama and Mrs. Clinton. It made me laugh, anyway. What was I doing there?

Thirty-fifth floor.

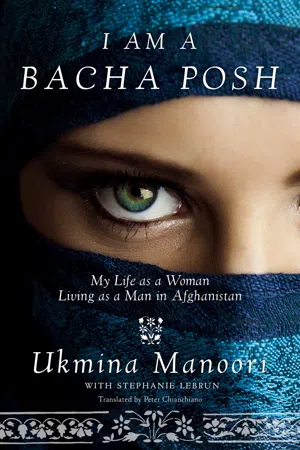

I was wearing a black turban with thin white stripes on my head, and some locks of gray hair had escaped. A beige shalwar kameez, a jacket without sleeves made of gray wool: my men’s uniform. Masculine shoes, those of a stranger, of a Westerner. I have dressed this way for nearly forty years, since I decided to be a bacha posh, a woman dressed as a man.

Thirty-first floor.

Was it this outfit that had led me there, to the heart of the US Department of State? Among women from all over the world chosen to receive the award for Most Courageous Women of the World? And to think that three months ago, I had never heard of March 8, Women’s Day.

This was all because of Shakila. She came to find me during a seminar at Kabul: “We thought of you, Ukmina. You were chosen to represent Afghanistan. If you want, you can join the delegation that will go to New York for March eighth.”

This was in January. I thought about it and agreed. Anything that talks about my people is better than nothing. I had the right to be accompanied, to bring someone of my choice, someone who spoke English. My husband, for example. But I was not married, and no one understood this language in my family. I almost refused the invitation then.

I was scared, I admit. Me, Ukmina, the one who had fought the Russians, the one who shook the hand of President Karzai, all of a sudden, I was returning to my former life: I was just an illiterate peasant from southern Afghanistan. A Pashtun without a destiny. But then I thought about Badgai, who lit up my life; who in her men’s garb transgressed the laws, clothing, and fears. And so I got on the plane. But to be honest, I was still nervous.

I was going so far, I told myself; there would be all of these women who had certainly done incredible things in their lives. And me, what was I going to say? I made myself sick with these thoughts. I had a fever for many days before my departure. The plane ride was horrible, a nightmare. It was long, and I could not understand anything. We landed in Washington and then took off again for New York. And then I was there, in the elevator.

Twelfth floor.

A man entered. Western. Handsome in his gray suit. He looked at me, surprised. I saw that he did not know with whom he was dealing. Hello, sir? Hello, madam? He preferred not to choose, smiled timidly, and turned his back to me. In Khost, my province, they called me “uncle” on the street. We say this to mature men. Officially, I am forty-five years old, but I look fifteen years older than that. The story of my life shows in my face; the wrinkles are profound.

Second floor.

I was at the US Department of State! And again I thought about Badgai, the strong and brave woman who had the courage no “true” man ever had. Badgai, who asked King Amanullah for an explanation for the assassination of her two brothers. Badgai, who had come back, sad and proud, with their bodies on her horse. Badgai, the man with a woman’s body, the woman at the heart of a man, the light of my life. I dedicated that moment to her.

Ding! Lobby.

The elevator tone brought me back to America. It was terrifying. There were more people there than I had ever seen in my whole life. Women, so many women. All courageous, I suppose. But I did not like them. They talked and laughed so loudly, to the point that I wanted to cover my ears sometimes. And they had this way of dressing . . . nude legs and shoulders and necks. I had never seen this before, neither in my village, obviously, nor in Khost, nor in Kabul, nor in Mecca, nowhere I had ever been until then. The free woman. Was this it, freedom? Giving up your body for all to see?

Freedom, for me, is to be respected. And for this, one must respect others and not impose something on them they do not want to see. These women were doctors, lawyers, engineers who came to speak to me. These women had fulfilled their wants, their talents; these women had transformed their luck of being born in the right place at the right time into a tool. These women had the opportunity to become successful—something that we Afghans could not do. Unless we were cunning, denying a part of ourselves, denying being born female, for example. And for this, we needed courage and sacrifices.

People I did not know introduced me to other people I did not know. They took pictures of me. Listening to their whispers brought me back to being one of the Afghans in the delegation who understood a little English: “They are talking to you, Ukmina. They are calling you Ukmina the Warrior!” Others called to me, “It’s you, the Afghan woman dressed as a man!”

Sometimes I would smile, sometimes I would make myself look mean, pressing my lips together while slightly narrowing my eyes, like I had in the elevator earlier in front of the mirror. Women from Iran, Iraq, and Germany asked me questions: Was it common for an Afghan woman to dress as a man? Were there others? Yes, I knew that I was not alone. Some told me: “You are a hero—a heroine!” What were they saying?

I attended to speak about our country, about the status of women, the war, the future. I did not hold back, I wouldn’t miss an occasion to retell the mess of the American intervention: “You came into Afghanistan, you brought in your dogs, they came into our homes. We Afghans, we hate dogs, dirty animals that scare the angels and prevent them from visiting us. You did not understand our culture.” I am not saying that this is why I didn’t win the prize for the Most Courageous Woman of the Year, but it must not have helped! The winner was Afghan, another kind, someone well educated. But I did not regret it. This was my job, I represented my country. I couldn’t hide the truth and not say what everyone thinks. This is how I am. This is why I wrote this book. So I could tell the truth about Afghani women.

Because I lived as a man for most of my life, I could do this today. What a paradox! But I was seizing the opportunity. I learned not very long ago that I was the only Afghan to know of such a special fate. In our country, we, the bacha posh, the “women dressed as men,” made ourselves discreet. No one could say how many of us there were. We made the choice in a single moment of our lives not to renounce the freedom that our simple masculine clothes give but to risk our lives every single day. I wanted to write this book before I became an old woman or ill, before I was no longer able to remember my life, my special fate. Everyone wanted to know why some Afghan women made this choice. I think that from reading what I am going to recount of my life, they will understand. I want them to talk about us, the Afghans who fight to no longer be ghosts, to come back to the visible world. To no longer hide ourselves under burqas or men’s clothing.

![]()

2

“YOU WILL BE A BOY, MY GIRL”

I never knew my date of birth. At home, we did not celebrate birthdays. On my identity card, it says I was born in the year 13461 on the Iranian solar calendar, the calendar that all Pashtuns use. It’s a guess, an approximate date; I do not have a birth certificate, no official documentation that announces my arrival into the world. When I was asked for a form of identity, my mother made up stories: you must have been born around 1346, she would tell me. Give or take two years or so. It was sometime in the spring, that she was sure of. She remembered everything else, for when I came out of her belly, my parents wondered if I was going to survive. They had already lost ten children.

I like my mother’s name, Soudiqua, “an honest person” in Pashtu, our language. It’s what my mother was: honest, and brave. Her life was like that of all the women here. A life of submission. An orphan, she was married at fifteen years old. In our community, a woman without a father and without a brother is a woman without protection: they need a husband as soon as possible. She found my father, fifteen years her senior. He owned land and animals: sheep, goats, cows, donkeys, and a camel. He was one of the richest people in the village, one of the most respected. His large beard was already turning gray; it gave him an elderly look, and, in his spare time, he would sort out neighborhood problems when the villagers would consult him. They were a good match; my mother managed well. She lived in her in-laws’ home: a mud-brick farmhouse on the outskirts of the village, surrounded by almond trees. In the center was a well that had been constructed by my grandfather, who is no longer on this earth. Life revolved around this sole source of water until night fell. Then, darkness fell over the home like a starry cover, a lead weight. Electricity never made it to our region, closer to Pakistan than Kabul. In the course of time, the everyday routine had not changed much throughout the centuries.

Three years after their marriage, my parents had a son, my older brother, who is still alive. Then, for ten years, a curse fell over the couple. Seven girls and three boys were born under their roof, among them two sets of twins. None of them survived. The only one who lived longer than one year and overcame all the infant maladies drowned six years later.

My father was a brave man, in his own way. He liked to follow the local customs. Beating his wife was one of them. When the children died at birth, for some weeks or months later, he would take his grief out on my mother and beat her violently. “Your father is cruel,” she said to me one day in one of her rare moments of defeat and discouragement. I was seven years old, and I did not understand anything. But I already knew that I didn’t want this life, my mother’s life. My mother had lost her parents when she was still a child and then her own babies. Her life was summarized by the loss of her loved ones. She hardly ever talked about her suffering—her fate was to suffer, to be quiet—when we would speak of the past, she would brush the air with the back of her hand “Miserable times . . . don’t ever look at the past, go toward the future, try to have a good life.”

When I lived through the first day, my father immediately knew I was going to survive. He waited a month, and, watching me get bigger and put on weight in unusual proportions, given the poverty of the land, he used this phrase, which changed the course of my life: “You will be a boy, my girl.” My mother did not oppose, as she also needed a son. My older brother was already ten years old. My parents needed another boy to help provide for the home, run errands, take care of the animals, work the land, do men’s jobs—the jobs they have the right to do. We are Muslim and Pashtun, and there are rules: a woman cannot be seen alone in public; this considerably restricts their range of activities.

From that moment on, by the will of my parents, my family and my neighbors had to consider me like a brother, to forget that I was born a girl, and to call me Hukomkhan, “the man that gives orders,” and no more by my birth name, Ukmina. If acquaintances came by the house with presents for a girl, my father would decline and say, “This is my son, and not my daughter.” I therefore became Hukomkhan. My father was proud of me. When I was five years old, he put me on his shoulders and walked around the village, making me look like a trophy: I was the long-awaited son. He bought me candy, sweets, chocolate, and beautiful clothes. At eight years old, to reward me for my work, he gave me the most beautiful present that I had ever seen in my life: a bicycle! It was amazing. I got on and admired the way we looked, my bike and me, in a small mirror that I held out at arm’s length. My brother patiently taught me to pedal without losing balance. It was not easy to do on the rocky roads near the village. I was happy! Free. I no longer felt the burden of my difference, because I did not see it.

In our district, to state that a girl is a boy was nothing exceptional. In the village, there were about fifteen of us dressed like our brothers, in blue shalwar kameez, a long tunic over pants. There were Jania and Sakina, Matgullah, Geengatta, Sharkhamatha, Kamala, and Mamura. Families without sons and without descendants have the right to cross-dress one of their daughters to preserve the family’s honor. It is also said that this can ward off bad luck for the future children: the bad luck being the birth of a girl. One superstition concealed a more pragmatic reason: to dress a girl as a boy allowed them to help the family, because she could work and bring home money.

Kamala, for example, did not have a brother, but six sisters. It was she who supported the home; she served tea in a shop. Her relatives knew she was a girl, but the customers took her for a boy and found no problem with having their favorite drink served to them by this child whose hair was hidden under a hat and who wore masculine clothing. If Kamala had not made up herself this way, the shop manager would not have hired her: girls did not work—they stayed in the house! Of course, they knew that Kamala was a girl, but because she was disguised this way, the honor was preserved, and all the world was content.

This is an old tradition in Afghanistan. Everyone knows the story of King Habibullah Khan, who reigned from 1901 to 1919: he modernized the country and brought in Western medicine and initiated many great state reforms. In his palace in Kabul, he had a very modern idea: to guard his harem, he designated one of his daughters to dress in the clothing of a man. Before, there were eunuchs, emasculated and harmless men to look after the women of the emir. He devised a new plan. What’s better than a woman to look after other women? And what’s better than a man’s uniform to direct with authority the king’s mistresses? His youngest daughter therefore took the place of the eunuch until the death of her father, who was killed while out hunting. It is said that afterward, she refused to go back to wearing women’s clothing and ran away under the identity of a man. Nobody ever heard of her again.

I didn’t know if Kamala was happy in her situation. She didn’t have the choice to tell the truth; I had the impression that she was of those girls who preferred to keep their hair long to publicize their identities more than hiding it, lying. For me, it was not a problem—quite the opposite! I knew that I was a boy deep down inside my heart, and that the destiny of a man awaited me. I do not lie.

Kamala explained to me one day that I should not get attached to my boy clothes. “When you are ten years old, we will go back to being real girls. My cousin served tea here up until last year, but she is too old now. She wears the veil, and she helps her mother in the house. You will see that you, too, will have to, and you will go back to Ukmina. If not, Allah will punish you, and so will all the mullahs!”

Kamala was right. I knew well that the majority of girls abandon the masculine clothing around ten years old, but I knew a certain Bibi who could help me keep my appearance as a man. She was the same age as my mother, worked at the market, and she had the strength of a man. Word had it that she had killed someone during a fight about land.

When we went to the bazaar, I looked at her out of the corner of my eye. She scared me but also intrigued me. I never dared say a word to her. The villagers call these women bakri, a word that means “women without desire,” those who give up marriage to stay near to their parents. Nobody here uses the expression bacha posh, a Dari expression, the language of Kabul.

Little girls like me make up part of the landscape: there is no specific name designated for us, no label. We are integrated into the community, even if we have a different life.

At seven years old, when the other girls began to wear a sadar, a simple veil only covering the head, we ran in the mud with the boys. My playmates went to school; my father did not see the use in sending me, since I was a girl. I dreamed of learning to read and write. I watched them leave at dawn; I didn’t not understand why I couldn’t follow them. One night, I took my courage in both hands.

“Father, why do I not have the right to go to school?”

“Because there are no schools for girls.”

“But I am not a girl! I work in the fields like the boys, I guard the sheep in the mountains, I play with them . . . so why can I do everything they can except go to school?”

“Because it isn’t worth it; you do not need to.”

The discussion was over for the day. But I came back to it many times, for weeks and months. I was nine years old when my ...