![]()

Part I

Introduction and conceptual issues

![]()

1

An introduction to consumptive wildlife tourism

Brent Lovelock

Introduction

This book explores the field of touristic hunting, shooting and sport fishing. It investigates contemporary trends in the industry, and suggests some possible futures for the sector. Consumptive wildlife tourism, while arguably neglected in current tourism research, has become an increasingly contested domain. Animal rights activists and environmentalists argue that it contributes to the demise of some species, and that practices such as ‘canned hunting’, ‘virtual hunting’ (but with real game) and the use of hounds are unethical. Concurrently, however, many remote, indigenous or developing communities around the world are strategising on how to capitalise on potentially lucrative consumptive forms of wildlife tourism. This book, through a series of case studies from around the world, considers the argument for growing consumptive wildlife tourism, looking at the relationships between hunting, fishing and local communities, impacts, economies and ecologies.

Consumptive wildlife tourism (CWT), as a niche product, has received relatively little attention from researchers. This may be attributed to a number of reasons, including the relative lack of visibility of this sector not only in terms of its economic scale but also in terms of any large physical infrastructural presence. It is also possible that tourism researchers have tended to treat hunting and fishing as non-touristic activities, leaving the sector to leisure and recreation specialists. A further reason for lack of research may relate to the fact that hunting and shooting are not generally popular pastimes of the educated middle class, and furthermore, that as a field of research the topic falls between the uncomfortable (guns, firearms) and the unforgiveable (killing Bambi). As Dizard observes: ‘Nice people don’t hunt’ (2003:58). Nice people prefer to drink wine, go on gastronomy tours or visit heritage buildings in Tuscany. No one wants to research people performing unpleasant acts.

Consumptive wildlife tourism in the tourism world

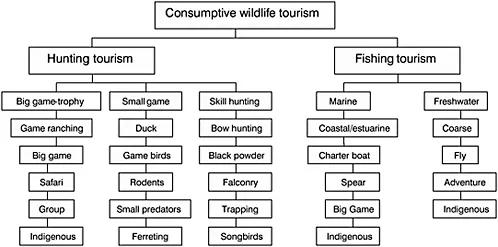

As a niche tourism product, namely a small specialised sector of tourism which appeals to a well-defined market segment, CWT fits into the broader nature-related macro-niche of wildlife tourism (Novelli and Humavindu 2005). Wildlife tourism includes activities classified as ‘non-consumptive’; that is, wildlife viewing, photography, feeding and interacting in various ways, as well as ‘consumptive’ activities. The latter may include killing or capturing wildlife, i.e. hunting, shooting or fishing. The most popular forms of CWT are illustrated in Figure 1.1. Bauer and Herr (2004) use the hunting/fishing dichotomy, and sub-divisions based upon game and/or habitat. Their representation is useful for showing the diversity of forms of CWT. For the purposes of this book, CWT is defined as a form of leisure travel undertaken for the purpose of hunting or shooting game animals, or fishing for sports fish, either in natural sites or in areas created for these purposes.

However, CWT is more than just about killing animals, and participants demonstrate a range of motives with respect to the experience they seek. A typology of hunters (and the same could probably be said for fishers), has been constructed and includes nature hunters, meat hunters and sport hunters (Kellert 1996). Thus, we see a range of purposes and immediately that CWT has some commonalities with eco-tourism and sport tourism, participants thereof who have a range of motivations. Indeed, some definitions allow us to view CWT as a form of sport tourism (e.g. Gibson et al. 1997 in Delpy-Neirotti 2003), and the sporting aspect of CWT is strongly apparent in the way that participants score their performances. There are a number of scoring systems employed for hunted and fished species – for example the ‘Boone and Crockett’ system for big game and the ‘Douglas’ scoring system for ungulates, while sporting prowess in fishing is expressed in terms of the weight of a fish caught.

But CWT is also a form of cultural tourism, when defined as the ‘… search for and participation in new and deep cultural experiences, whether aesthetic, intellectual, emotional, or psychological’ (Stebbins 1996:948). There is often a strong sense of cultural exchange between hunters and fishers and their hosts (see Foote and Wenzel, this volume). This may be particularly obvious when CWT is organised by, or engages the services of indigenous peoples, and especially

so when traditional hunting or fishing practices are used. And in a heritage tourism sense, arguably consumptive wildlife tourists, especially hunters, may seek not just the experience of the hunt, but also to recreate a sense that they are amongst the ‘first’, are ‘pioneers’, and imagine in doing this that they are like the Victorian gentleman-hunter. This is especially seen when hunters adopt primitive technologies such as black-powder rifles. For many hunters from the new-world, an attraction of CWT in the old-world, where hunting remains of great cultural significance (Bauer and Herr 2004), may be the rich heritage of hunting evoked through dress, protocol and arcane practices such as ‘blooding’ the hunter.

It is clear that CWT is a multi-dimensional practice, rather than a simple act of killing. CWT is a sport, and as such is culturally embedded and can be a heritage experience, an adventure and an ecotourism experience. Radder’s (2005:1143) study of trophy hunters suggests that the CWT experience is not driven by a single motive, but by a ‘multidimensional set of inter-related, interdependent and overlapping motives’ falling within the realms of spiritual, emotional, intellectual, self-directed, biological and social motives. The importance of a number of motives is illustrated in Radder’s study, most clearly by the finding that participants valued the concept of experiencing new places, people and culture higher than collecting hunting trophies. And while CWT could also be conceived as a form of adventure tourism, Radder’s research shows only weak support for risk as a major motive of hunting and fishing tourists. What we can be assured of, however, is that serious consumptive wildlife tourists are highly motivated – demonstrated by a survey of British sport fishermen which revealed that more than half would rather catch a record-breaking trout or salmon than spend a night with a supermodel (Otago Daily Times 2006).

Scale and scope of CWT

Hunting, shooting and sport-fishing are immensely popular recreational activities. Fishing, for example, is one of the most popular forms of outdoor recreation in many countries. Estimates of participation rates in the United States, for example, indicate that up to 16 per cent of the adult population fish (USDOI et al. 2002). In Australia the fishing participation rate is estimated at 19.5 per cent (FRDC 2001), while Japanese participation in fishing is slightly higher at 23 per cent (SB&SRTI 2006). A national angling survey in the United Kingdom in 1994 estimated that there were 3.3 million fresh and sea water anglers, while in the wider European Union there are an estimated 25 million recreational fishermen.

Participation in hunting is generally lower however. In New Zealand, the participation rate is put at about 2 per cent of the adult population (Groome et al. 1983), and in Australia a mere 0.35 per cent (Australian Sports Commission 2006). In the United States, 6 per cent of the adult population hunt (USDOI et al. 2002).

But not all of these recreationists become consumptive wildlife tourists in the traditionally accepted use of the term tourist. And to complicate matters, there is some debate about what constitutes a tourist. The US Travel Data Center considers tourists to be those that take trips with a one-way mileage of 100 miles or more, or all trips involving an overnight stay away from home, regardless of distance travelled. Other definitions rely upon an individual crossing a border to become a tourist. The World Tourism Organisation (WTO 2006) defines tourism as comprising the activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes. They distinguish between inbound tourism (from another country) and domestic tourism, the latter involving residents of a given country travelling within that country. It is generally considered that to be a tourist, an individual must spend at least one night away from their home, however, the WTO also notes the importance of same day visitors to the ‘tourism’ industry. Clearly, the definition of what constitutes a tourist is somewhat loose and problematic. However, for the purposes of this book, consumptive wildlife tourists are taken to be those that travel to fish, shoot or hunt in a region other than their own.

Unfortunately, accurate figures are not kept by many national tourism organisations on the numbers of inbound consumptive wildlife tourists – a fate of many forms of special interest tourism (McKercher and Chan 2005). So the ‘conversion’ rate of domestic or recreational hunters and fishers into consumptive wildlife tourists is largely unknown. Furthermore, McKercher and Chan argue that existing data relating to inbound special interest tourism is unreliable in terms of identifying that special interest as a primary activity or motivator. So, data from international visitor surveys such as those undertaken in New Zealand which identifies that fishing was undertaken by 2.6 per cent of inbound visitors (Ministry of Tourism 2006), and in Australia where 4 per cent of international visitors engaged in fishing whilst in the country (FRDC 2006) are interesting but not definitive in terms of identifying if CWT is a primary motive for visiting a destination.

Estimates at this stage, of the total market size, therefore, are fraught with lack of precision. Work within the United States, however, comes closest to estimating market size. Hunters combined with fishers, total a substantial 47 million people who engage in either activity (USDOI et al. 2002). Fishing tourism in particular appears to contribute substantially to overall visitor-days, with a very high number (estimated 70 million) of out-of-state fishing days (Ditton et al. 2002). Collectively US$20 billion was spent on trip-related expenses for both hunting and fishing (USDOI et al. 2002).

Naturally, in this process, some states end up as net gainers and some as net losers in terms of fishing tourism days. On an international level, this is what Hofer (2002) refers to as demand and supply countries, where some destinations gain from inbound CWT. Traditionally North America and Western Europe have been important both in terms of supply and demand for international CWT, although both of these regions have their own substantial domestic CWT markets (or in the case of Europe, domestic plus intra-European markets).

However, new demand and supply countries are emerging, and while this may be producing only marginal effect upon the global distribution of income from CWT, substantial local effects are arising (see Foote and Wenzel’s chapter in this volume on hunting in Nunavit, in the Canadian Arctic). A typology of CWT destinations around the world is offered belo...