1 Fermented marine food products in Vietnam

Ecological basis and production

Kenneth Ruddle

Eastern mainland Asia is the realm of umami (‘good taste’; cf. Kawamura and Kare 1987), where the amino acid and salty tastes of fermented products enter the cuisine. There, much of the salt intake is from either the daily consumption of fermented foods or condiments. It is also the principal region of irrigated rice cultivation. Generally, in most of East and Southeast Asia, where rice is the staple carbohydrate, there is a high consumption of fish and fish products. So the predominant dietary pattern is fish combined with rice, which provides vegetable protein, amino acids and energy. Thus in this dietary culture a side dish used to facilitate consumption of large amounts of rice is indispensable. Such dishes are characteristically small in quantity and highly salty. Fermented products are the most suitable items for this purpose. They also have the advantage of being simple to preserve and have a long shelf life. Further, they do not require elaborate cooking for each meal. Fermented products also impart umami and a salty taste to vegetable dishes, which inherently lack these flavours.

The seasonal pattern of the monsoon is the main ecological driving force of Southeast Asia, when seasons of abundance and scarcity of food resources alternate according to the stage of the monsoonal circulation. Fermentation of fish and other aquatic organisms is one ancient technique used throughout East and Southeast Asia to provide an animal protein as well as a savoury side dish and condimental complement to rice in the seasons when fresh fish is either scarce or unobtainable. Fermentation is used to produce soy and fish sauces, the dominant condiments throughout the region (Ishige and Ruddle 1987, 1990; Kimizuka et al. 1987).

Despite a long and close cultural association with China, fermented soybean products did not develop in Vietnam. Instead, fermented fish products have always been used. In Vietnam, as in the rest of the region, the marine fish species deliberately targeted for use in the fermentation industry share three basic characteristics. They are (1) readily available in large quantities to permit bulk, low cost fermentation; (2) caught easily and in safe locations, to reduce labour costs and hazard, respectively; and (3) require little highly specialized or expensive fishing gear to catch. In addition, all the species meet certain physical criteria to ensure easy and even bulk fermentation, and are inexpensive, with few if any more valuable economic uses. Therefore, most marine species routinely preserved by fermentation are small, of low economic value and are seasonally abundant in inshore marine and brackish waters, in large shoals, that are easily captured with relatively simple gear (Ruddle 1986). In contrast, at other times of the year they are scarce or absent in the same locations. Since, with few exceptions, the fish utilized are juveniles, they are of low economic value and, apart from conversion into animal feed, have few alternative economic uses.

Although any species of fish can be fermented to produce fish sauces and pastes, by preference, because of the inherent chemical characteristics of certain species, as well as biological rhythms that favour uniform harvesting in bulk, only relatively few species are used in Vietnam. There, apart from the Indo-Pacific mackerel (Rastrelliger sp.), Gizzard shads (Anodontostoma chacunda and Nematolosa nasus) and Round scad (Decapterus spp.), the fish fermented are all clupeoids (Round herring [Spratelloides spp.], sardines [Sardinella spp.] and anchovies [Coilia spp., Setipinna spp., Stolephorus spp. and Engraulis spp.]) (Ruddle 1986). Thus, the fish used are mostly planktivores that depend on the plankton blooms generated by the upwelling induced by the offshore monsoon. And most of the marine fish utilized to make fermented sauces and paste are either juveniles or young adults, since the length of those used is about 50 per cent of the total body length (TBL) of adults.

In all cases the species used and the size needed are abundant, at particular coastal locations, only during certain times of the year. I have demonstrated elsewhere that the fundamental biological rhythm exploited by this fishery is the feeding and recruitment migration of juvenile planktivores (Ruddle 1986), which depends on the seasonal location of coastal upwellings induced by the prevailing offshore monsoon winds that give rise to phytoplankton blooms (Ruddle 2005).1 In other words, the seasonal and diel2 behavioural characteristic exploited by the fisheries that supply the fermentation industry is the tendency of the juveniles of the finfish species utilized to aggregate in vast shoals in shallow inshore marine and brackish estuarine waters for feeding. In all cases, this behavioural characteristic permits large quantities of fish to be captured, using relatively simple fishing gear, and in relatively shallow, sheltered and safe inshore waters.

The ecological basis of the fishery

The ecological basis of the fermentation industry in Vietnam are the physical oceanographic factors associated with the monsoons that cause local upwelling and, therefore, increase primary productivity in marine waters, and the seasonality of their biological rhythms. The driving force is the pattern of monsoon seasonality.

The large-scale atmospheric circulation in Southeast Asia is characterized by the northeast monsoon, the southwest monsoon, and two inter-monsoonal periods. The northeast monsoon lasts from about mid-October until March, when air flows basically north to south across Southeast Asia. At this time of the year strong onshore winds and heavy precipitation are experienced along the coasts of Vietnam, apart from the southern and west-facing coasts in the south of the country. The southwest monsoon season lasts from mid-May until September, when wind and precipitation patterns are essentially the reverse of those prevailing during the northeast monsoon. The two inter-monsoonal periods are transitions between the two monsoons. One occurs from late-March through May, and the other from late-September through November. Inter-monsoonals are characterized by frequent changes in the direction of the prevailing winds, and by variations in duration; from three to twelve weeks with the March–May transition period generally being longer.

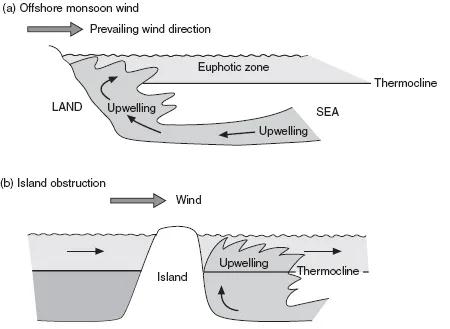

That pattern of monsoon seasonality drives the seasonal pattern of vertical water movements. A very simplified explanation of the mechanism is that the fish production of any sea area depends on the fertility of its water,3 or on the level of primary production of phytoplankton, the photosynthesis of which in tropical seas occurs in a euphotic zone that extends to a depth of about 200 metres.4 However, in tropical seas a strong and persistent thermocline usually inhibits the water mixing5 and so limits primary production because dead organisms and excreta, which provide the nutrients for phytoplankton growth, sink into the deeper waters beneath the thermocline. Nutrients are therefore gradually depleted in the euphotic zone, the fertility and fish production of which declines.

Thus, upwelling or vertical water movements that seasonally disrupt the thermocline and restore the temporarily lost nutrients to the productive cycle in the euphotic zone are fundamental to the fertility of the sea and to fish production. When nutrient-laden waters are thus restored to the surface a ‘burst’ of phytoplankton growth occurs, followed by a growth in the zooplankton population, and, in turn, an increase in the population of both planktivorous fish and those piscivores that predate on them. The spawning and feeding patterns of fish are adapted to this seasonal sequence of the loss and restoration of nutrient levels. Thus the occurrence of upwelling, which is caused by a variety of physical factors, is of fundamental importance to both the fish production of an area and the fishery based on it (Figure 1.1).

In Southeast Asia coastal upwelling is caused mainly by the prevailing offshore monsoonal wind flow.6 Thus the location of areas of coastal upwelling, and therefore of fishing activity, changes seasonally according to the prevailing direction of the monsoonal winds. During the season of the northeast monsoon upwelling occurs on western, southwestern and southern coasts, and during the southwest monsoon it occurs on eastern, northeastern and northern coasts.

Conversely, during the monsoon season with prevailing onshore winds the reverse process operates. At this time of the year nutrient-rich waters are kept below the thermocline by the piling-up of surface water against the coast, under the pressure of the prevailing wind. Thus, without replenishment from below the thermocline, the euphotic zone undergoes a decline in nutrients and a concomitant decline in populations of phytoplankton and fish.7

Figure 1.1 Principal causes of upwelling in the coastal waters of Vietnam (after Ruddle 1986).

The relationship between fishing season and monsoon seasonality

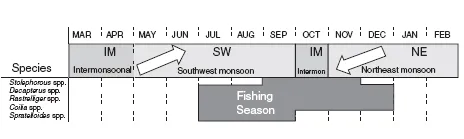

For the physical and biological reasons discussed above, most coastal fishing in Vietnamese waters is conducted during the monsoon, when the prevailing winds are offshore, when coastal upwelling, therefore, occurs, and during the intermonsoonal (IM). In the coastal waters of Vietnam, anchovies (Stolephorus spp.) are taken from September until November, i.e. from the end of the offshore southwest monsoon (SW), through the inter-monsoonal, and into the beginning of the onshore northeast monsoon (NE). Coilia spp. and Rastrelliger spp. are caught for a somewhat longer period, from July to December. Anchovies of the genera Setipinna and Engraulis are caught only from July to September, i.e. only after the prevailing offshore winds of the southwest and the coastal upwelling that it induces are firmly established (Figure 1.2).

Hypothesis on monsoon seasonality and the biological rhythms of fish

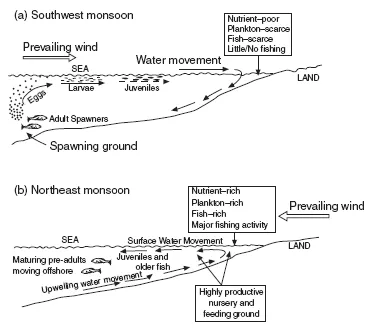

Since most of the fish fermented are small, pelagic, schooling planktivores, their feeding behaviour depends on spatio-temporal variations in the location of plankton, which, in turn, depends on monsoonal seasonality. Further, since these fish are subject to high predation pressures it can be supposed that in their reproductive strategy they migrate away from inshore zones, where predation rates are extremely high, to spawn in offshore areas where the pressure is less intense.

Figure 1.2 Relationship between the fishing season of selected fish species and monsoon seasonality in Vietnam (after Ruddle 1986).

Figure 1.3 Hypothesis on fish behaviour and the monsoons (for a Western Coast) in Vietnam (after Ruddle 1986).

For the small pelagic fishes of concern here, however, I hypothesized (Ruddle 1986) that intense predation inshore leads to offshore spawning migrations at times and in places where the eggs and larvae are assured of being swept coastwards. They should also spawn at times and in locations where their eggs would not be flushed further offshore, and, on the contrary, when winds, currents and gyres would ensure a steady coastwards drift of eggs, larvae and post-larval forms. Thus at an early juvenile stage they would arrive at their plankton-rich inshore feeding grounds (Figure 1.3).

Thus, depending on the distance offshore of the spawning grounds, spawning of the migratory species should occur towards the latter part of the onshore monsoon. This would ensure that the post-larval forms reach inshore waters, where phytoplankton blooms are rich, as a consequence of the upwelling induced by the offshore monsoon, either before the winds of the offshore monsoon cause them to drift further out to sea, or just after they have developed the swimming ability as newly recruited juveniles. In the latter case they could swim against the wind-induced current and reach the inshore feeding grounds prior to the intense and persistent development of the monsoon (Ruddle 1986).8

Types of fermented fish product

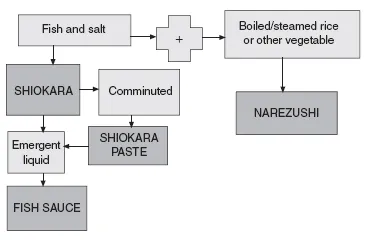

A wide range of fermented fish product is produced in East and Southeast Asia. A simple generic classification is shown in Figure 1.4, based on the nature of the final product and the method of preparation. The prototypical product is probably shiokara, made by mixing fish and salt, and which preserves the original whole or partial shape of the fish. When comminuted shiokara yields shiokara paste, which has a condiment-like character. Fish sauce is prepared from the process of making shiokara. If no vegetable materials are added the salt-fish mixture eventually yields fish sauce, a liquid used as a pure condiment. The intent, however, particularly in commercial situations, is to prepare fish sauce and not shiokara. Narezushi is produced if cooked plant materials are added to the fish and salt mixture (Ishige and Ruddle 1987).

Fish sauces (nuoc mam) in Vietnam

Fish sauce is a condiment widely used throughout Asia, and especially in continental Southeast Asia, where processes range from simple procedures to satisfy household needs through large-scale factories using industrial techniques. In Vietnam the mainstay of the fish sauce industry is large-scale production in specialized communities, using highly elaborate techniques, but household and cottage industry production is widespread and varied. The generic production process for fish sauce manufacture in Vietnam is shown in Figure 1.5. Three stages may be distinguished: (1) preliminary processing; (2) salting the fish and filling the fermentation container; and (3) drawing-off the sauce.

Figure 1.4 Generic classification of fermented fish products in Asia.

Figure 1.5 The generic production process of marine fish sauce (nuoc mam) in Vietnam (adapted from information in Nguyen and Vialard-Goudou 1953).

Where whole fish are used, preliminary processing consists just of removing all foreign matter. Elsewhere it is more complex. The fish are classified according to size and inherent salt content when a system of compression and just one salting is used. The different sizes and salt content types are treated differently. Further, the level of the inherent saltiness of fish varies by season, being higher in summer. The fish is also classified by the number of scales and thickness. Large ones are cut into pieces prior to salting.

Salting rates and the method of filling the container depend on the species used and their inherent salt content. When Round scad (Decapterus sp.), miscellaneous stolephorid and other anchovies (Engraulis spp.) are being used, the fermentation container is divided into three sections. In the bottom section the fish are salted (by weight) at 1:0.5, in the centre the rate is 1.5:1 and at the top 1.2:1.

The fish are left thus to disintegrate slowly. The time required for this varies according to species. Dorostoma nasu and miscellaneous species require 12 months, since they are bony and their flesh tough. But Decapterus requires four months and Engraulis mystax and Stolephorus sp. will disintegrate in 3.5 months. The precise length of the fermentation period depends on the seasonal climate. It is faster in summer. It also depends on the size and type of fish being used, as well as on the attention paid to the processing. Small, soft-boned fish ferment faster than large fish with many scales and thick flesh. The first grade of sauce (...