![]()

Chapter 1

A multimodal social semiotic approach

Introduction

This book explores how language and literacy classrooms can become more democratic spaces through addressing a central issue in teaching, learning and its assessment: namely, the forms of representation through which students make their meanings. In this sense, the book is about the politics of representation and the politics of difference in diverse, multicultural and multilingual classrooms. It focuses attention on the forms of representation which are produced from the many cultural sources students have access to, and examines these resources for their meaning potential. To put it simply, this book examines the question: how can the classroom, as a multi-semiotic space, become a complex, democratic space, founded on the productive integration of diverse histories, modes, genres, epistemologies, feelings, languages and discourses?

Drawing on theories in the emerging field of multimodal communication from a social semiotic perspective, this book locates itself within a paradigm shift that is taking place in relation to conceptualising communication and representation in learning environments. Following the work of Kress (1995, 1997a, 2000a, 2003), Kress and van Leeuwen (1996, 2nd edn 2006, 2001) and van Leeuwen (2005), this shift has been described as a multimodal approach to representation and communication. In the field of literacy education, this approach has been variously referred to as ‘multimodal literacy’, ‘multimodality’ and ‘multimodal social semiotics’. Traditional theories of communication are monomodal in their focus on how language communicates meaning. However, a multimodal theory of communication holds that meaning is made, always, in the many different modes and media which make up a communicational ensemble. A multimodal approach to teaching and learning characterises communication in classrooms beyond the linguistic: language, in speech and writing, is only one mode of communication among many. Other modes can include image, space, gesture, colour, sound and movement, all of which function to communicate meaning in an integrated, multilayered way. In a multimodal approach, all modes of communication drawn on in the making of meaning are given equally serious attention.

The shift from a focus on language to a focus on mode has resulted in a shift in the relevant theoretical fields, from the discipline of linguistics, which focuses on language, to semiotics, which studies signs and their meanings in all their different material realisations. The semiotic framework which this book draws on is social semiotics, signalling its emphasis on the social dimensions of how human beings represent their meanings in the concrete social world. Social semiotics fundamentally challenges the idea of closed, stable systems of representation in which human beings are users of systems, rather than active transformers of semiotic resources. Social semiotic theories place human beings at the centre of meaning–making: as designers and interpreters of meaning, they make active choices, according to their interests, from the semiotic resources available to them. Semiotic resources of representation are not fixed: they are fluid, constantly changing as human beings’ representational needs change. Thus, from a social semiotic perspective, communication as sign production, ‘reception’ and transformation, can be understood as a product of how people work with, use and transform the semiotic resources available to them in specific moments of history, culture and power.

This shift from an emphasis on language to mode has far-reaching implications for education. As Kress et al. (2001, 2005) have demonstrated in Science and English classrooms, the idea that each mode provides teachers and students with a range of meaning–making potentials or ‘affordances’ has consequences for learning, the shaping of knowledge, the development of curriculum and its assessment practices. It has implications for students’ identities and how cultures and identities are shaped in learning environments. This shift has important implications for thinking about pedagogy: if all pedagogic processes, including the designing of teaching and learning materials, are understood as the selection and configuration of the multimodal resources available in the classroom, then pedagogical processes can be viewed as complex signs of what it is that the producers of this sign ‘needed to’ or ‘chose to say’ at that particular moment. The producers of these signs may include the state, national curriculum designers, schools and their boards, parents, school subject departments, individual teachers and students. Such processes of sign-making are never neutral, however. They are invested with unequal power relations, resource constraints and forms of coercion and resistance operating among different interest groups in the educational policy-practice nexus (Bhattacharya et al. 2007). For example, in South Africa, how HIV/AIDS education is mainstreamed in the school curriculum is an area of fraught debate and controversy which gets ‘actualised’ by individual schools and teachers in a myriad of ways. Any investigation, at the micro level, into how it is taken up and enacted in classrooms by teachers and students has to be read against the macro socio-political context of tension between denial, silence and stigmatisation of the disease, and open acknowledgement and action focused on treatment and prevention.

This book shows how a multimodal semiotic approach can be applied to educational practice to enhance learning in contexts of diversity and difference. As such, it takes a critical perspective (Freire 1970; Mclaren 1989; Giroux 1992; Luke 2004; Norton and Tooney 2004) in relation to multimodal semiotics, arguing that classrooms have the potential to become ‘transformative’ sites in which students’ representational resources can be used productively and critically to develop curricula and pedagogies which speak to the diversity of global societies and the development of students’ voices. It links the building of democratic culture specifically to the forms through which students are permitted to make their meanings. In mainstream classrooms, certain forms of representation are dominant and valued, like standard forms of written language. Students who do not perform ‘to standard’, for whatever reasons, are labelled as ‘deficient’. In this book, I challenge the idea of the dominance of a single form of representation. Rather, I explore how different knowledges and cultural forms can be represented through multiple forms of representation, how these diverse forms can be ‘remixed’, rubbed up against each other to create new forms, new meanings and new possibilities for learning, what Millard (2006) calls ‘fusion’ pedagogies. This is not to deny students access to dominant discourses of power, but to reconceptualise teaching and learning as holding in creative tension access to dominant discourses, while building on the rich variety of resources that students bring to learning contexts. Such pedagogies can be harnessed for establishing classroom cultures in which social and cultural difference is valued positively, as a resource, not as an obstacle.

These issues are addressed through examples from South Africa in the post-apartheid transformation period (1994 to present). South Africa is presented as a high instance of a democracy in formation, as a whole society engages with what it means to move from a colonial history and deeply racialised, officially segregated white minority-controlled state to a modern African capitalist democracy founded on constitutional rights, equity, reconciliation, redress and inclusivity. The examples in this book have been selected mainly from projects in narrative in language and literacy classrooms, where students from different language and cultural backgrounds negotiate ongoing tensions in the society between ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’, between Western and African forms of intellectual thought, consciousness and culture, between local African languages and English, between indigenous, local knowledges and new information technologies, between schooled learning and out-of-school knowledge, between the apartheid-past of their parents and their own aspirations for the future.

Three stories

1980s

This research began in the 1980s during the last decade of apartheid rule in South Africa, when I started working as an English teacher with young children and teachers in Soweto, then a segregated township for black people on the outskirts of Johannesburg. I was concerned at that point with the stark contrasts between the children’s worlds inside the classroom, and what they were witnessing and experiencing outside the classroom. Inside the classroom, where they were learning English as an additional language, they were chanting textbook drill and pattern practice of English grammatical forms, answering questions in variations of controlled composition, and reading strange colonial texts about African children living in remote rural villages. This was going on whilst all around, an urban political war was being waged: the apartheid army was patrolling the streets in casspirs (armoured vehicles), high–school children were being shot and tortured, buildings were being burnt and school boycotts called. I wondered where children were being given the opportunity to connect learning in classrooms with their everyday lives. At the same time, I was constantly hearing racist, deficit remarks in (white) educational circles concerning the linguistic, creative and cognitive abilities of black children.

As a response to these views, and with a deepening sense of the lack of connection between children’s home lives and school lives, a colleague, Martha Mokgoko, and I started running afternoon classes in a local community centre in Soweto with groups of young children. We called our group SPEAK. We were working in an intensely stressful political situation of violence and brutality. The day we started our classes, the government declared a state of emergency. Troops patrolled the streets and the army was invading schools. We constituted these classes as ‘unpoliced zones’ where children could explore and represent their worlds in playful, imaginative and uncensored ways that combined multiple discourses and modes of representation. It was in that space that it became clear the extent to which children’s daily experiences in classrooms were constraining and denying them opportunities to flourish as fully expressive human beings. In denying these children the capacity for voice, schools were functioning as another arm of apartheid surveillance and control.

Many of the roots of my interest in innovative or ‘alternative’ pedagogies grew out of a political response to the teaching situation in which we found ourselves: the media were severely restricted by the emergency regulations and any reports of ‘unrest’ or political resistance in any of the black townships were heavily censored. Two guiding principles formed the core of our language learning and teaching approach: what we called ‘a genuine search for meaning’ within ‘an atmosphere of freedom and learner responsibility’ in which children were encouraged to listen to each other and respect each other’s rights to different opinions. Teachers were encouraged to listen to and respect the opinions of children. This mutual respect was hard to engender in South Africa, where, historically, there has been no tradition of religious, racial or political tolerance.

It seemed clear to us that any language pedagogy which had as its core aim ‘a genuine search for meaning’ had to start with children’s lives and daily experiences in some form of critical engagement. A primary aim was to develop children’s ‘voices’. As such, this pedagogy was deeply influenced by Freire’s critical pedagogy (1970; Freire and Macedo 1987) which had already impacted on several of the progressive adult education programmes in South Africa at the time. We wanted to promote a culture of talking rather than fighting and help children to reflect critically on the social and material conditions of their lives so they could understand the root causes of the violence they were witnessing and experiencing. At the time, this ‘culture of talking’ was developed in and through one language – English – because I was committed at that time to working in an ‘English as the target language’ teaching model. Since then I have changed my views: developing a ‘culture of talking’ means working with all the language resources that children have access to. In Gauteng, where I live and work, most children are multilingual, drawing on several African languages in their communicative repertoires.

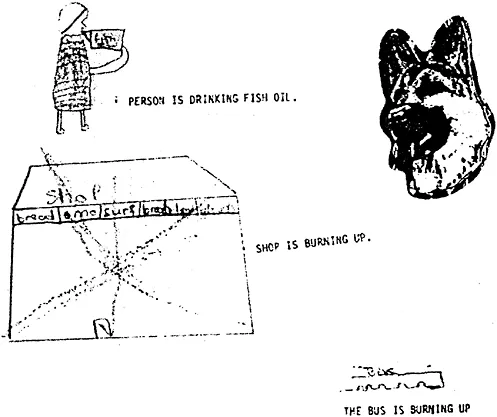

Language was not the only mode of communication, however. Because children had different levels of access to English, and talking was potentially dangerous, there were many instances where they wanted to tell their stories through dance, music and performance, with no watertight divisions between them. Drawing became a more direct way of showing what was difficult to describe. These sessions became known as ‘Behind the Headlines’ because in a very real sense, most of the experiences witnessed or reported on were suppressed in the national media. These multimodal texts then became the primary texts around which discussion and critical reflection would happen. Figure 1.1 is an example of drawing and writing by SPEAK children in the late 1980s about a notorious incident when youth from the liberation movement, the African National Congress (ANC), were forcing people to boycott shops in the city and to stop using state-owned transport in the form of buses. Those who defied this boycott were forced by ANC youth ‘comrades’ to drink fish oil or soap powder on their return from these shops. Buses were being burnt at the same time.

Drama was used extensively to explore current themes and events. Martha Mokgoko made a play with the children based on the true story of one of the children, a 12-year-old Soweto boy, whose father had saved up to buy him a bicycle for his birthday. One afternoon, three thieves robbed him of his bicycle at gunpoint. Frank’s older brother went looking for the thieves and found one of them. He called his father and they both assaulted the thief, took him to the police who released him without charges. Frank never reclaimed his bicycle. The play ended with a poem by the children, pleading for joint community action against the high levels of violence and crime in Soweto. Apartheid was cited as one of the major causes of this crime rate. Here Martha Mokgoko describes the process of making this story into a play, Frank’s Bicycle: