![]()

Part I

‘Within the system’

Asian immigration and the European labour market

![]()

2

Not all can win prizes

Asians in the British labour market

Giles A. Barrett and David McEvoy

1979 was an important year for British politics and for the British labour market. Margaret Thatcher’s first government came to power and began a regime change in the regulation of the economy. This was maintained under Thatcher’s Conservative successor, John Major, and, with some exceptions, under Tony Blair’s 1997 Labour government. Public utilities and other state-owned industries were transferred to the private sector. The right to strike was restricted, and Wages Councils, which regulated pay in low-paying industries, were abolished. State benefits for the unemployed were reduced, particularly for the young. Limits on shop opening hours in England and Wales, introduced by a Labour government strongly influenced by the shop workers’ trade union in 1950, were eliminated. These and other measures exposed employers and workers to the rigours of the market in a way which would have been politically unthinkable, whatever the party in power, between 1945 and 1979. Unemployment was allowed to more than double to well over three million. Moreover official definitions of unemployment were revised over twenty times so that figures in newspaper headlines became less dramatic.

During the 1990s, however, Britain’s unemployment fell again to below the level applying in most other EU members. This is widely interpreted as a measure of the flexibility introduced into the economy by the post-1979 reforms. In contrast to many of its major European partners the United Kingdom is no longer seen as a corporatist state in which the rights of workers and their trade unions are strong determinants of national policy. The restructuring of industries has proceeded rapidly. Coal mining for example has disappeared as a significant employer. Manufacturing too has suffered many job losses. Meanwhile many service industries have been growing, including health, education, hotels, catering, finance, and professional services.

The growing ethnic minority populations have not therefore entered a stable opportunity structure. The number and nature of employment openings have been constantly changing. More jobs have become temporary. Success in this environment may be dependent on a dynamic mix of endeavour, experience, qualifications and adaptability. Britain’s Asian minorities are popularly thought to have performed well in this context, particularly in comparison with the African-Caribbean community. This is a viewpoint based partly on the multiplication of Asian-owned retail and restaurant businesses, activities which are highly visible in urban areas.

In order to assess the impression of Asian success this chapter looks first at the migration history and population characteristics of the main Asian groups. Consideration is then given to their educational attainments as preparations for employment. Attention then turns to engagement with the labour market, including levels of participation and unemployment. After this the differential presence of Asian communities in broad economic sectors is considered. The distinction between male and female experience is kept in view throughout. Particularly in the examination of sectors, the experiences of the immigrant generation are contrasted with those of their British-born descendants.

Demographic and educational background

Britain’s Asians have their origins in the imperial past. In the twenty years following the Second World War streams of migrants from the Caribbean, from South Asia, from Hong Kong and from other quarters of the disappearing empire were established. Most of the newcomers, as citizens of former or current British colonies, held British passports. In spite of recurring moral panics, most notoriously characterized by the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech of Enoch Powell, these migrations were a response to the economic needs of British society. Immigrants came to fill the vacant job niches in the economy. In a period of economic growth and full employment, positions which were poorly paid, or involved long hours or unpleasant conditions, were no longer attractive to the indigenous population. Industries such as the foundries of the Midlands and the textile factories of Lancashire and Yorkshire relied on immigrants to maintain their competitiveness. Male newcomers, sometimes actively recruited from overseas, often staffed night shifts which were unattractive to white males and illegal for female workers (Kalra, 2000:96). Similarly the National Health Service and train and bus operators plugged staffing gaps with immigrants of both sexes.

This replacement labour phase did not, however, continue. Primary immigration became much more difficult under laws of 1962, 1968 and 1971 which changed the passport entitlement of colonial and former colonial citizens. Nevertheless family reunification continued to be allowed, so that wives and children were able to join men who, for reasons of economy, had originally migrated alone. Now the passage of decades, with births and education in Britain, had the unintended consequence of turning possibly temporary migrant populations into settled ethnic minority communities. The sojourner mentality of the original migrants, and the associated ‘myth of return’ (Anwar, 1979), were supplanted by the recognition that minorities were ‘here to stay’ (Bradford Heritage Recording Unit, 1994). Meanwhile immigration on the basis of work permits, for those with professional qualifications or specialist skills, continued on a restricted basis, and some foreign students and asylum seekers were also able to gain admission.

Government data have struggled to define these evolving populations. Until the 1971 census only birthplace and previous residence were recorded. Continuing this practice would have rendered the growing number of children, born in Britain of immigrant parentage, statistically invisible. In 1971 a census question was asked about parental birthplace. The 1981 census dealt with the matter by inference: ethnic minorities were identified on the basis of the birthplace of the head of the household in which a person resided (Coleman and Salt, 1992:483–6). Only in 1991 were census respondents asked directly about ethnicity. This was repeated in 2001, although the results have been classified slightly differently from ten years earlier. Additional complications arise from differences between the categories enumerated and reported in Scotland and those used in England and Wales. Northern Ireland even has a separate census, resulting in further variations in ethnic classification (NISRA, 2003).

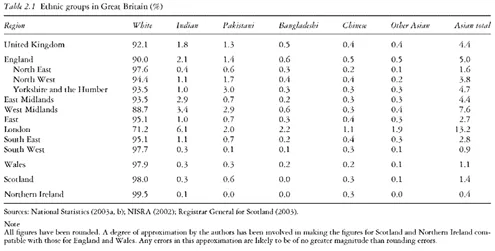

It is nevertheless possible to compile comparative figures for ethnic groups for the United Kingdom’s constituent countries, and for the government regions of England. These geographical differences are important to Asian labour markets because variations in economic structure and prosperity provide different opportunity structures in different places. Table 2.1 presents population data for the Asian groups identified by the census. For purposes of comparison it also includes figures for the white majority. A residual category, consisting partly of persons of black descent, partly of those of mixed ethnicity, and partly of persons of other non-Asian descent, is omitted. The white group is predominantly British in origin, but also includes the Irish, other Europeans, and some from former colonies of white settlement.

The figures show that Britain is a predominantly white country, with ethnic minorities comprising about 8 per cent of the population. Rather more than half of these, 4.4 per cent, are of Asian origin. The picture is, however, geographically varied. In more peripheral regions, including the ‘Celtic fringe’ of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, ethnic minorities are less than 2.5 per cent of the population, with the Asian share ranging from 1.6 per cent in north-east England to 0.4 per cent in Northern Ireland. In the rest of England the minority proportion is higher, with figures ranging from 4.9 per cent in the East to 28.9 per cent in London. Two main explanations can be discerned. First, old industrial regions have minority populations which have developed from the arrival of replacement labour in earlier decades. Second London, which also attracted migrants in this earlier phase, functions as a ‘global city’ and consequently continues to attract migrants, both to the upper tiers of the labour market and to the low-paid service jobs which support the lifestyle of the affluent sectors of the metropolitan elite (Sassen, 2001).

Table 2.1 Ethnic groups in Great Britain (%)

Within these overall patterns particular Asian minorities display different geographies. The Chinese are the most evenly distributed group. In all regions except London they are present as a small minority of between 0.2 per cent and 0.4 per cent. This wide dispersal is a reflection of their concentration in a single economic activity, the Chinese restaurant or take-away, which was virtually ubiquitous as early as the 1970s (Watson, 1977). Even in Belfast’s notoriously segregated districts, the Protestant Shankill and the Catholic Falls, Chinese food outlets provide reminders of the possibility of multicultural life. The picture in London differs. Although Chinese cuisine is as available as elsewhere there is also a concentration of those with professional and technical qualifications. These people have more widespread origins than those ...