- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forming Nation, Framing Welfare

About this book

This book introduces a historical perspective on the emergence and development of social welfare. Starting from the familiar ground of 'the family', it traces some of the crucial historical roots and desires that fed the development of social policy in the 19th and 20th centuries around education, the family, unemployment and nationhood. By aiming to discover the link between past and present, it shows that social problems are socially constructed in specific contexts and that there are diverse and competing ways of telling history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forming Nation, Framing Welfare by Gail Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1: A Family for Nation and Empire

by Catherine Hall

1 Introduction

The worlds of welfare and that of ‘the family’ are intimately connected. Open any newspaper, listen to numerous radio broadcasts, watch a range of television programmes and the issue of the family in the UK is likely to be among the most frequent topics of public debate. Among ‘experts’ and lay people alike arguments and speculations over the links between increasing diversity in family and household forms and those issues defined as ‘social problems’ rage on. Indeed, this increasing diversity in family and household forms is itself often defined as a social problem. Connections to the worlds of social policy and welfare practice are made in the form of whether or not lone mothers create delinquents and therefore should not be supported by having access to welfare benefits and services. Questions as to the moral messages which are sent to impressionable youth by such support are raised, whilst the potential this support for lone mothers offers fathers, to avoid their parental and conjugal responsibilities, is deeply regretted.

All these—and many more—are testimonies to the deep connections made in the minds of politicians and policy makers between ‘the family’ and social policy. How new a connection is this? And if such a connection has a long history, is it possible to discern shifts or continuities in these lines of connection? What of the wider social and discursive context—how did this impact upon the lines of connection? These are some of the issues which inform this chapter.

The aim of this chapter is to introduce you to:

- ■ The historical specificity of family forms.

- ■ The emergence of ‘the family’ as a key site of social order in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

- ■ The celebration of a particular kind of family as natural and proper, other kinds of families as unnatural, disorderly and in need of regulation by philanthropists and the state.

- ■ The social construction of some working-class families as social problems and in need of transformation for ‘the good of the nation’.

- ■ The social construction of Irish migrants and their familial practices as a source of ‘pollution’ to the nation.

- ■ The attempt to reorder gender and familial relations in the Empire as well as ‘at home’ in Britain.

- ■ A critical relation to notions of history and historical evidence.

2 The historical specificity of the family

Since we tend to think of the family as a ‘natural’ institution, we also tend to think of it as an institution which has been immemorially fixed in the ways in which we know it as an ideal—the breadwinning father and the dependent wife and children. The significant changes which have taken place in the family and household in the last 20 years—such as the growth of lone-parent families, the increase in women’s employment, the increase in men’s unemployment, the rate of breakdown of marriages, the increase in single-person households, and so on—all tend to be presented as departures from the norm. But what if the norm were not quite as fixed as we think? What if the family were a much more flexible institution historically than we tend to imagine?

families

There is, of course, no essential ‘family’, but always families’. Until the late eighteenth century the concept of family was significantly different from that with which we are familiar now. Indeed, in the early eighteenth century no word existed which meant ‘only kin’ within a household: servants, lodgers, visitors, pupils, shopmen and unrelated children might be included in the term ‘family’. This unit was under the control of the paterfamilias (the literal meaning of which is father of the family): father, husband and master, who represented his dependants to the wider body politic. Only gradually was he himself seen as part of, rather than outside, that unit. Boarding and visiting took place on a large scale and casual dining at the tables of relatives and friends was constant. In other words, a more flexible concept of family was in operation than the one which is now dominant, or most familiar, in the UK.

The notion of a family tied closely to blood, to two generations of parents and children, to co-residence and to a male breadwinner, became much more common in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries, a period which saw the transformation of Britain.

2.1 The transformation of Britain

The combination of the growth of population, the shift from agriculture to industry, the rapid expansion of towns and cities, the construction of mills, mines and railways which transformed the landscape, and the reorganization of social and political relations all added up to the construction of what felt to many in the population like a new social world. Combined with this was the expansion of the British Empire—an essential part of this new pattern of global commodity capitalism. By 1815, at the end of the long war with France, Britain had recovered from the major setback associated with the loss of the American colonies in the War of Independence and ruled a quarter of the world’s population. Items such as sugar and tea, which were becoming the benchmarks of a particularly British culture, came from that Empire. The Empire provided raw materials to fuel the British industries: cotton from India, linen from Ireland and wool from Australia. At the same time it provided a marketplace for British manufactured goods and a site on which English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish men, and to a much lesser extent women, could hope to make new lives and fortunes. The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were experienced by many in Britain as a time of rapid and extraordinary change, a time when the world and their own society looked different. Of course there were many continuities, but it was also a time of transformation.

Take the town of Birmingham, which in 1801 had a population of 74,987. By 1851 that population had grown to 246,961. Migrants had come from the surrounding countryside and from farther afield—Ireland in particular. The shift from a relatively small town to what was to become a city meant that the physical landscape was dramatically altered. Contemporaries were struck, above all, by the noise and turmoil of this great working town, by the sight and sound everywhere of ‘earnest occupation’, as the novelist and critic Charles Dickens described it in his immensely popular The Pickwick Papers. ‘The streets were thronged with working people’, he wrote:

The hum of labour resounded from every house, lights gleamed from the long casement windows in the attic stories, and the whirl of wheels and noise of machinery shook the trembling walls. The fires, whose lurid sullen light had been visible for miles, blazed fiercely, in the great works and factories of the town. The din of hammers, the rushing of steam, and the dead heavy clanging of engines, was the harsh music which arose from every quarter.

(Dickens, 1836–37, p. 801)

It was the transformation of work which first impressed itself upon the contemporary imagination: the new processes, the new products, the factories, the machinery, the power. It was industrialization itself which seemed at the time responsible for the production of new class relations. As Frederick Engels, Karl Marx’s long-time collaborator and friend, put it in his classic description of Manchester in 1844:

The history of the proletariat in England begins with the second half of the last century, with the invention of the steam-engine and of machinery for working cotton. These inventions gave rise, as is well-known, to an industrial revolution, a revolution which altered the whole civil society… England is the classic soil of this transformation…

(Engels, 1845, p. 35)

Note that Engels talks about England, not Britain. It was England which was commonly discussed at this time as the heartland of industrial change, despite the importance of the Scottish lowlands in that process, to take only one example. The marginalization of the peripheries, as Scotland, Ireland and Wales were seen by those in England, was part of the process whereby England was constructed as the centre—the key to Britain, the crucial economic site, the cultural heart and the political pulse of the nation. What happened on the fringes, it was thought, was of much less significance than what happened in the metropolis. In this way of constructing the world it was events in that metropolis which determined what happened in the peripheries—and not only in the near peripheries of Scotland, Wales and Ireland, which together were seen as constituting Britain, but the farther flung reaches of the Empire, those colonies which were, like Australia or Canada, outposts of the motherland, or, like India or Jamaica, dependent territories to be ruled by their ‘betters’.

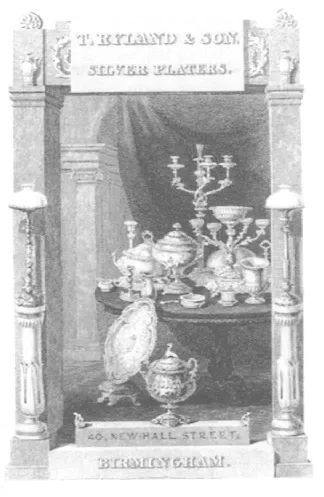

For Engels, England provided the classic example of industrial transformation, the emergence of a new kind of society structured by capitalism. It was spinning jennies, steam-engines, factory production and cotton which had transformed Manchester. It was small workshop production on a hitherto unimagined scale which made Birmingham famous for its harsh music of anvil and stamp, press and lathe, hammer and file, all dedicated to the production of metal goods. Its shops were remarkable for their dazzling displays of steelware and plated goods, brass and jewellery, nails, pins and screws. Its workshops boasted new divisions of labour of the sort which had fascinated Adam Smith and convinced him that a new civilization was being constructed. The expansion of Birmingham in the eighteenth century rested on the development of the Staffordshire coal and iron industries and the improvements in transport which opened up not only the markets of the south and west but also those of the colonies. Birmingham’s jewellery and plate, pistols and daggers, buttons and buckles, brass bedsteads, cables, chains and anchors, locks and bolts, were heavily dependent on colonial markets. As J.C.Tildesly, a lock manufacturer, put it:

Of the future of the lock trade in this district we can speak with promise. The development of new empires, and the opening-up of fresh fields of commerce in our colonies, augur well for this department of local industry, and we have faith that the locksmiths of South Staffordshire will keep their place before all rivals. The demand for locks and keys must necessarily extend with the growth of civilisation.

(quoted in Timmins, 1866, p. 91)

The assumption in this passage that civilization and private property go together is striking. In those new colonial settings the brass candlesticks, lamps and casters, kettles and pots, needles and screws, steel pens, silver plate, glass and chemicals, for which Birmingham was famous, graced middle-class homes just as they did in the ‘mother country’, while they serviced the kitchens of both settlers and those at home. Indeed, using ‘home’ products was a way of continuing to feel English in the colonies, while for the colonized, in the minds of the colonizers, it was seen as a way of becoming ‘civilized’. Indeed, some of those who were colonized themselves believed they could become English by acquiring and consuming English culture.

Advertisement for Birmingham silverplate which was intended to grace the tables of the middle classes

Economic and industrial change brought urban growth. Birmingham’s expanding population needed housing, transport, new facilities. Canals and railways cut across the town, overcrowded working-class neighbourhoods were gradually marked off from new areas of middle-class housing, town life was increasingly regulated, new public buildings were erected.

class

In 1844 Engels wanted to characterize the new epoch which Manchester, and England, symbolized for him. He explained what he saw as the key changes in class relations—the emergence of the proletariat and of the bourgeoisie as two great classes facing each other in antagonistic relations—as a result of technological change. In analysing the development of modern industry, as he called it, Marx placed his stress on the dynamic power of capital itself—on its capacity to reorganize the relations of production in order to make possible the continual accumulation of profit (see Marx and Engels, 1848). This reorganization, as Adam Smith (1776) had noted, could take place in workshop or in factory, with water-power or hand tools. The relations which were transformed were those between masters and men, with the wage as the symbol of those new relations in which traditional rights, customs, duties and obligations had been abandoned and the cash-nexus—the sale of a person’s labour to the capitalist in exchange for a money payment—had triumphed.

It was the language of class which provided a way of articulating the changes in social relations associated with the development of industrial capitalism. In feudal society land was the indicator of power. In capitalist society, finance capital, mercantile capital and manufacturing capital achieved dominance over land, and the landed classes had to reach a new settlement with the men of capital. Workers also had to find a new settlement with their employers and, in the process, an identity for themselves as members of the working classes. The language of class—utilized in somewhat different ways by political economists; by analysts and cultural critics such as Marx, Engels, Thomas Carlyle and Charles Dickens; and by working-class Radicals in the Chartist movement—provided a way of describing what was new and different about English society in the early nineteenth century. It provided the frame for understanding why the changes which were being experienced by working men and women and by factory owners, merchants and professionals and their wives, were epochal, the mark of a new time.

In this epochal change it was not only the relations between capital and labour that were reworked. The historiography (that is, the body of historical writing) of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain has emphasized the centrality of class. This is partly to do with the centrality of class to contemporaries’ own understanding of their society and partly associated with the influence of Marxism and the labour movement on the writing of that history. Thus two of the most influential accounts of this period—E.J.Hobsbawm’s Industry and Empire (1968) and E.P.Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963)—structure their narratives through the axis of class. Those class relations, however, were always gendered and since the 1970s feminist historians have begun to tell different stories, with their focus on women and gender as well as on class. Masters were men and their authority derived from their position as men as well as their position as employers. Their wives, as Davidoff and Hall (1987) argue, found themselves increasingly defined, and increasingly defined themselves, as wives and mothers rather than as mistresses of an enterprise which included family, kin, apprentices and employees.

gender

At the same time male and female workers were constituted as different subjects in the labour market, earning differentiated wages, placed in different occupational sectors, with skill being defined as associated with men. How did this happen and what discourses enabled it to become ‘common sense’? The language which articulated these changes in the representation and ordering of gender relations was that of ‘separate spheres’. This language demarcated the worlds of men and women, distinguishing sharply between ‘public’ and ‘private’—men were associated with the world of work and the public, women with the world of home and the private. Only men were supposed to move with ease through these two worlds. This language became naturalized: men were born to be public and women private. Men were naturally suited to be captains of industry on the one hand, labourers on the other. Women were naturally daughters, wives and mothers. This language of naturalized difference provided the dominant understanding of reordered gender relations in the epoch of modern industry.

If class and gender relations were being reworked in this time of epochal change, so were ethnic relations. While feminism and the Women’s Movement of...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Social Policy: Welfare, Power and Diversity

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A Family for Nation and Empire

- Chapter 2: ‘Remoralizing’ the Poor?: Gender, Class and Philanthropy in Victorian Britain

- Chapter 3: Education for Labour: Social Problems of Nationhood

- Chapter 4: Education for ‘Minorities’: Irish Catholics in Britain

- Chapter 5: Patterns of Visibility: Unemployment in Britain During the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

- Chapter 6: Families of Meaning: Contemporary Discourses of the Family

- Chapter 7: Review

- Acknowledgements

- The Open University Course Team