1 Between a colonial clash and World War Zero

The impact of the Russo-Japanese War in a global perspective

Rotem Kowner

On the morning of February 6, 1904, Japan severed its diplomatic relations with Russia. The same day, the Japanese Combined Fleet under the command of Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō set sail for the shores of Korea. Off the port city of Chemulpo, in the vicinity of the capital Seoul, the force split into two. Most of the warships made for Port Arthur while a small naval force under Rear Admiral Uryū; Sotokichi remained to protect the landing of the army on Korean soil. On the night of February 8, ten Japanese destroyers attacked Russian warships anchored in the harbor of Port Arthur but did not inflict much damage. The following morning the Japanese forces of the First Army took control of the Korean capital while Uryū’s naval force demanded of the Russian naval detachment in Chemulpo that it leave the port. The Russians obeyed, but, following a short offshore engagement, they returned to the port and scuttled the cruiser Variag and the gunship Koreets rather than hand them over to the enemy. These seemingly trivial episodes were but the prologue to a colossal struggle. The next day Japan declared war, whereupon a 19-month war began officially.1

From a broad historical perspective, the Russo-Japanese War was the long-anticipated flashpoint of the enmity between two expanding powers. On the western boundaries of Asia the Russian Empire had been advancing relentlessly southeastward for centuries, while on the eastern fringe of this continent the Japanese Empire had been spreading westward for three short decades. The difference in the extent of their imperialist expansion, however, did not diminish the magnitude of the conflict, and additional dissimilarities only made its resolution by diplomatic means ever less feasible. In fact, apart from their imperialist aspirations, their recent modernization, and their technologically advanced armies, there was little similarity between the two states. They differed in the size of their territory, population, and economy, as well as in their racial composition, language, and religion. Eventually, the encounter between them took place in the killing fields of Manchuria and Korea, areas both sides were eager to control. It was not their first or their last confrontation, but certainly it has exerted the greatest impact on both.2

Historiographically, views on the significance of the Russo-Japanese War have undergone tremendous fluctuations since its outbreak and throughout the subsequent century, shifting from sensation to amnesia and recently revived recollection. Present readers might be surprised to discover that the Russo-Japanese War was not an unknown event at the time of its occurrence. On the contrary, for such a peripheral conflict, it generated enormous reverberations. It was an astounding war, and millions around the globe kept abreast of the news of the surprising victories of “little” Japan over the “mighty” Russian Empire.

In the following years many prominent figures who shaped the history of the twentieth century referred to the Russo-Japanese War and remembered acutely the sensation it created. Adolf Hitler, for example, was one of those who took the war seriously, so much so that it might have contributed to his early evolving Weltanschauung. Serving his sentence in Landsberg prison two decades after the Russo-Japanese War and writing his fateful manifesto Mein Kampf, Hitler’s memory of it was still vivid. In 1904 the future Führer was 15 years old, and the war found him “much more mature and also more attentive” than during the Boer War, in which he also took, he confessed, great interest. He at once sided with the Japanese, and considered the Russian fiasco “a defeat of the Austrian Slavic nationalities.” 3 Hitler, of course, was not alone in understanding the importance of that event. Many others, particularly in Asia, regarded the war as a formative event in their political upbringing. During the hostilities India’s future leader of independence, Mohandas Gandhi, for example, grasped from remote South Africa that “the people of the East seem to be waking up from their lethargy.”4 Similarly, Sukarno, Indonesia’s first president after its independence, appraised Japan’s victory in retrospect and viewed it as one of the major events affecting “the development of Indonesian nationalism.” 5

Less than a decade after its conclusion, however, the war was hardly mentioned again, and after another three decades its claim to fame had vanished completely. Overshadowed by two global conflicts, and suffering from the demise of both regimes that took part in it, the Russo-Japanese War was virtually forgotten in the second half of the twentieth century. It was more or less destined for such a fate, as from an early stage this titanic struggle was customarily labeled merely one more clash in a series of colonial wars that afflicted the world throughout the nineteenth century.6 No wonder, therefore, that most history books dealing with the modern age make no more than a brief mention of it, and even today some fundamental issues of the war, such as the decision-making on both sides during the war, and the military campaign, still await a comprehensive examination that takes into account all sources available.7

A typical example of the prevalent disregard for the war can be found in Barbara Tuchman’s book The Proud Tower (1966), in which she sought to provide a portrait of “the world” in the three decades before World War I. In her preface this influential historian admitted that she adopted a very selective view in attempting to describe the image of the world during that critical period. Tuchman had no hesitation in stating that it might have been possible to include a chapter on the Russo-Japanese War, as well as a plausible chapter on the Boer War, Chekhov, or the everyday shopkeeper. But no, she chose to deal with what she believed were the main issues. Her writing is decidedly Eurocentric, and almost inevitably Tuchman ends by focusing on the Anglo-Saxon world, and then in descending order on Western Europe and tsarist Russia, while devoting only a few lines to the Russo- Japanese War—a critical juncture along the road to World War I.8

Among Western historians Tuchman is obviously not an exception. In fact, her tendency to look at the world through European spectacles and to ignore events outside the sphere of Europe and North America is rather the rule. Still, the blame for this historiographic amnesia about the Russo- Japanese War should not be attributed to Western myopia alone. Much of it was due to the proximity of the war to an even more important event, at least from a European point of view. There is no doubt that World War I (1914–18) was an event on a different scale. It changed the face of Europe and of the entire world, and created not only a new international system but also a different way of perceiving the modern era. Apart from the shadow cast by this subsequent colossal event, the Russo-Japanese War was forgotten simply because it happened “out there” at the distant edge of Asia, in remote and sparsely populated areas. The Japanese and Russians who fought it were considered the “Other,” obscure and anonymous troops, and their losses did not affect the hearts and minds of the public in the West. The military campaign was conducted amidst a local population that barely recorded its history, and the relatively few journalists who went to cover the fighting were kept under tight control and strict censorship. Their reports were also not immortalized by many visual mementos, since photographing equipment was heavy and the battle arena too distant, motion pictures had only just emerged, and live television broadcasts were still many decades in the future.

No less important, the two opponents themselves played an active role in diminishing the importance of their conflict. In Russia, soon to be transformed into the Soviet Union, the defeat emerged as just one more event in a long despicable series of fiascos associated with the “old” regime. With the Bolsheviks’ rise to power 12 years after the conclusion of the Portsmouth Peace Treaty, the defeat against Japan was turned into a war of the tsar and not of the people who fought to overthrow him.9 In Japan, by contrast, the victories of the war became an invaluable asset in the brief military legacy of the imperial forces. Nevertheless, at the time of its surrender to the Allies in 1945 Japan too began a process of suppression and denial of its imperial past, in a manner somewhat recalling what had happened to its Russian arch-rival several decades earlier. With such tortuous legacies, it would have been most unlikely for the memory of the war not to fade from national consciousness on both sides.

In the last few years the war has been widely commemorated and has received much more attention than in previous decades. Benefiting from the emergence of national consciousness in Japan since the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, it became again a valid topic for research and reflection. With the hindsight of a century it is possible to examine the war from an appropriate historiographic distance. By now all available documents related to the conflict have been declassified and analyzed, its heroes have all died, and the sensationalism that enveloped the battles is long gone. Today more than ever, it becomes clear that the war was not only of great importance at the time it occurred, but that it had an important impact on the entire history of the twentieth century.

A recent edited volume, The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero, seems to reflect the greater role that the war is given in current historiography. The editors of this volume contend that the modern era of global conflict began with the Russo-Japanese War rather than in 1914. In their brief introduction, they suggest that the war deserves this designation since it was fought between two powers, a European and an Asian, and was sponsored by a third party money market.10 While the title World War Zero admittedly sounds appealing, the Russo-Japanese War was not a global conflict. Not only did it involve directly only two adversaries, but for both of them it was far from a total war in the form they would experience in the following world wars. From Russia’s perspective, in fact, the clash with Japan was not a total war even in the sense of the Napoleonic Wars. During most of the campaign only a small segment of the Russian military machine was involved, and Russian casualties in Manchuria were far lower than those even in the Crimean War.11 No less important, no other power assisted either of the belligerents, and even their closest allies— Britain on Japan’s side and France on Russia’s side—did their utmost to avoid taking any active part in the conflict. Finally, the war did not witness the introduction of any revolutionary weapon, certainly not on the scale of the airplane, tank, or submarine, as was the case in World War I. All in all, it seems to resemble much more the Crimean War or even the American Civil War than any global conflict of the scale the world would experience twice within a 35-year period later on.

If the Russo-Japanese War carried any global significance it lay not in its origins in the actual warfare, in the diplomatic alliances, or in financial support obtained during the war, but in its repercussions. Although these were associated directly with the decline of Russia and the rise of Japan, they had a wide-ranging effect on numerous nations, regions, and spheres. Furthermore, these repercussions did not involve only immeasurable sentiments, such as fear, joy, or envy, but touched upon the economies and military organizations of every power in the early twentieth century, and its balance of power with others. Through this, the war affected the stability of Europe, Russia in particular, the equilibrium between the United States and Japan, and the territorial status quo in northeast Asia.

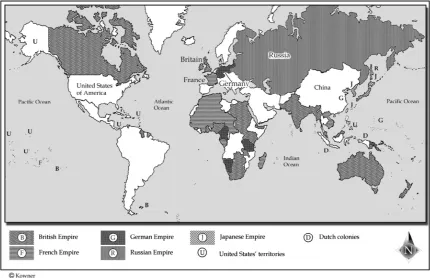

Map 1 World empires, 1904–14.

Implications for Europe: deterioration of the power balance

The Russo-Japanese War did not cause any instant or visible upheaval in Europe but its ultimate impact on this continent was devastating. It did not lead immediately to a substantial rise in military expenditure; nor did it start an arms race. It did not prompt any new radical attitude either, and even some of the political processes associated with it had begun to crystallize before the war broke out.12 More than anything, its impact in Europe was linked with Russia’s debacle in the battlefields of Manchuria and the consequent instability at home in the wake of the 1905 revolution. The status of Russia had in turn tangible, arguably even radical, repercussions on the power balance in Europe. Its impact was initially of a psychological nature and took shape in part during the war and in part after it, leading to a new balance, or rather imbalance, of power. The new political arrangement that emerged in Europe during 1904–5 was one of the precipitants, if not the main one, of the deterioration that led to the outbreak of the Great War less than a decade later.

Russia was not reduced to a marginal power following its final defeats in Mukden and Tsushima during the first half of 1905, but it unquestionably became second-rate in its image, its military capabilities, and its actual ability to influence others. The collapse of this mighty power undermined the political and military equilibrium that had endured in Europe since the Napoleonic era. While Russia lost its former military status, Germany had just completed a ten-year period of military build-up and during the war emerged as Europe’s supreme military and industrial power. The German rise was not a new phenomenon, but the Russian defeat suddenly highlighted the continental hegemony of Germany. The ascent of Germany had begun more than four decades earlier, and even before the war other European powers perceived it as jeopardizing the stability of the continent. However, the exposure of Russia’s military weakness, its naval losses, financial burden, and internal instability swung the already uneven military balance in Europe still more to Germany’s favor. In the subsequent decade the fluctuating balance between these two powers determined the fate of the continent. During 1904–14 this fragile equilibrium was in large measure, as David Herrmann convincingly argues, “the story of Russia’s prostration, its subsequent recovery, and the effects of this development upon the strategic situation.”13

Much of the road to the Great War was therefore associated with changing perceptions of this military balance by the German leadership.14 But, despite its economic and military hegemony, pre-war Germany was isolated and lacked a large empire overseas. The war in Manchuria provided Germany with a unique opportunity to reverse its prolonged failing diplomacy, which had begun to deteriorate since its last successful diplomatic collaboration in 1895 (the “Three Power Intervention” with France and Russia), aimed not by chance against Japan. Due to the sudden change of military power in 1905, Germany was able to pose a threat of war against its western neighbor France. The relu...