- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Through close scrutiny of empirical materials and interviews, this book uniquely analyzes all the episodes of long-running, widespread communal violence that erupted during Indonesia's post-New Order transition.

Indonesia democratised after the long and authoritarian New Order regime ended in May 1998. But the transition was far less peaceful than is often thought. It claimed about 10,000 lives in communal (ethnic and religious) violence, and nearly as many as that again in separatist violence in Aceh and East Timor.

Taking a comprehensive look at the communal violence that arose after the New Order regime, this book will be of interest to students of Southeast Asian studies, social movements, political violence and ethnicity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Communal Violence and Democratization in Indonesia by Gerry van Klinken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Studi sull'etnia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

The first time it happened was in Sambas district, West Kalimantan. It was January and February 1997. Newspapers reported that indigenous Dayaks began attacking migrant Madurese in their homes in the small town of Sanggau Ledo, then moved to other small towns around the district, sending tens of thousands fleeing for their lives. Indonesians were shocked. Collective violence between Indonesian citizens over communal identity had not happened before. Or rather it had not impressed itself on the public consciousness to this extent, for there had been several 1- or 2-day riots against Christians and Chinese in Java in previous months. This was on a much larger scale. The one-sided violence went on for weeks, and ranged across several districts.

The bloodshed was disturbing in itself, but something else was even more unsettling. It came from nowhere. It jarred the average Indonesian’s mental universe because it had no ready-made explanation. Indonesians had long known of violence in three remote places in their country – Aceh, Papua (then still called Irian Jaya) and East Timor. Although largely closed to reporters, they knew that secessionist sentiment was driving guerrilla resistance movements there, and that the Indonesian military had killed many in counter-insurgency operations. The state as the source of violence: this was as easy to understand for regime officials as for human rights activists. It was part of the common discourse about what was wrong with the New Order. And it happened closer to home as well. The big riot in Jakarta following a military-backed attack on the headquarters of opposition party PDI in July 1996 fitted the pattern. So did a litany of other incidents of military human rights abuse, such as the harbour-side shooting of hundreds in Tanjung Priok, Jakarta, in 1984, and the massacre in Talangsari village, Lampung, in 1989. A democratic state with the military on a short leash was the ideal to which everyone aspired, even regimists who believed the ideal lay still far off in the future. But the emotions evoked by the Sambas reports were different. Who were the baddies in this story? It was not clear. The military now seemed guilty not of causing it but only of not doing enough to stop it. The metropolitan press reported the story, but the opinion columns were remarkably silent on the profound moral question it posed. That question was, of course, how can Indonesia be a democratic country if in Sambas ordinary citizens attack each other for no better reason than cultural loathing? Where Indonesians did explain it, they often resorted to cultural stereotypes such as the savagery of Dayaks or (later) the irascibility of Ambonese. This explained nothing but the prejudices in the heads of the commentators, and obscured the real drama by writing any notion of agency out of the story. Where policy makers began to take them seriously – and they did in West and Central Kalimantan – they made things worse by institutionalizing racist sentiments.

The confusion in Indonesia’s opinion columns was enough reason to write this book. Living in that country gave me an appreciation of how seriously its public intellectuals take their calling. If they were at a loss it was because they had little to draw on. Since then the gap has been filling rapidly with Indonesian and foreign publications. We will look at some of this profusion of conference proceedings, journal articles and technical reports in the next chapter (see bibliography by Smith and Bouvier-Smith 2003). Several edited volumes have described the violence in this period (Anderson 2001; Colombijn and Lindblad 2002; Coppel 2006; Törnquist 2000; Wessel and Wimhöfer 2001). However, none focus on post-authoritarian communal violence as a single phenomenon. The same can be said of two single-author books. Bertrand (2004) brackets Christian–Muslim conflict in Maluku with separatist conflict in Aceh, Papua and East Timor as part of a general crisis in Indonesian nationalism. Sidel (in press) will be read mostly as a study in Islamist violence.

Two years after ‘Sambas’ fighting broke out between Muslims and Christians in Ambon, the largest urban centre east of Makassar. This was even more painful for the Indonesian public. Ambon could not be imagined as a battleground in the jungle. It was a thriving harbour town. Ambonese singers were famous in Jakarta’s sophisticated cabaret circuit. Moreover this was the reformasi era. President Suharto had resigned the previous May (1998) amid massive demonstrations. The dailies were full of democratic reforms in every sector. Ambon was a massive blow to the optimism that followed the end of the authoritarian New Order. Nor was this about some primitive tribal culture, as many metropolitans unkindly viewed the Dayaks, but about the two religions to which nearly all Indonesians belonged. And still the opinion columns offered few democratic answers, though undemocratic ones flourished in the sectarian press.

At about the same time, late 1998 and early 1999, communal fighting also erupted in two other places. In Sambas district, West Kalimantan, it broke out again, in a slightly different area but again leading to the expulsion of Madurese, this time perpetrated by indigenous Malays. And in Poso, a small town in Central Sulawesi, it broke out between Christians and Muslims. The bad news did not seem to stop. A year later, late 1999, escalating tensions exploded in North Maluku involving multiple theatres, some pitting Muslims against Christians, others Muslims against Muslims. The area lay over 400 km from Ambon and had its own dynamics. Then it happened in Central Kalimantan. In a pattern reminiscent of West Kalimantan, indigenous Dayaks attacked migrant Madurese in the harbour town of Sampit in February 2001 and then moved throughout the province expelling Madurese.

Taken together these six episodes in five places – West Kalimantan, Maluku (Ambon), Central Sulawesi (Poso), North Maluku and Central Kalimantan – described a distinct pattern of violence. They form the subject of this book. Unlike the secessionist violence in the three peripheral areas just mentioned, which had been running for decades, the violence in these five places was new. That is to say, it was not entirely without precedent. West Kalimantan Dayaks recalled a series of incidents with Madurese going back many years, and Ambonese Muslims remembered that the Republik Maluku Selatan (RMS) revolt of 1950 involved religious sentiment too. But the ferocity this time far exceeded that which had been seen earlier, while the identities involved were largely detached from claims about the nation, thus unlike the experience in Ambon in 1950. Each conflict was long running – from several weeks to years. Each claimed many victims – hundreds or thousands dead and tens or hundreds of thousands displaced. Each was widespread – ranging at least over a district (kabupaten) or an entire province. And each was communal – between groups within society along ascriptive lines of ethnic origin or religion, not explicitly about class and not against the state.

Recapping, this book concerns large-scale communal violence, because it is new in this country and needs to be explained. But it is not the only kind of collective violence that took on heightened forms at this time. An important question for subsequent work will be to see how all these troubles related to each other. We can distinguish four types.

- Secessionist violence. Best known was the paroxysm of military-sponsored violence in East Timor over the ballot in 1999 (Greenlees and Garran 2002; Tanter, Ball and Klinken 2006). Similar repressive violence was occurring in Aceh and, at a lower level, in Papua throughout this time.

- Large-scale communal violence, both inter-religious and inter-ethnic (the subject of this book).

- Localized communal riots. Several violent incidents occurred on the scale of one town or city and lasting a couple of days. Best known was the massive riot in Jakarta in May 1998 that led to Suharto’s resignation (Aspinall, Feith and Klinken 1999). Before that, short and sharp anti-Chinese riots had occurred in 1996–7 in the towns of Tasikmalaya (West Java), Banjarmasin (South Kalimantan), Situbondo (East Java), and Makassar (South Sulawesi) (Sidel in press). Afterwards Christian–Muslim riots occurred in Ketapang (Jakarta) and Kupang (West Timor) in November 1998 (Mas’oed, Maksum and Soehadha 2001).

- Social violence. Less well known, but claiming a significant number of victims, were ‘social’ phenomena such as vigilantism (lynching thieves) and inter-village brawls. These also showed a peak after the collapse of the New Order, yet without an evidently ‘political’ connection (Barron, Kaiser and Pradhan 2004; Welsh 2003). It occurred particularly in Java, Lombok and South Sulawesi (Varshney, Panggabean and Tadjoeddin 2004: 33). An intriguing series of murders against alleged black magicians in East Java late in 1998 appears to fall in between the more-or-less organized communal riots and social violence (Campbell and Connor 2000; Siegel 2001).

Terrorist violence could be considered a fifth type. It attracted a great deal of attention around the world after 9/11, and it has occurred in Indonesia (Sidel in press). However, it is committed by small groups of people acting in extreme secrecy, so cannot be regarded as collective violence to the same degree. By comparison with the other types of violence, it has also claimed far fewer lives, though the shock impact of these deaths has of course been out of all proportion to their number.

How many died? Non-secessionist collective violence has been estimated by the United Nations Support Facility for Indonesian Recovery (UNSFIR) to have cost over 10,000 lives in Indonesia in the period 1990–2003 (Varshney, Panggabean and Tadjoeddin 2004). This is the only national estimate by province and covers the entire transitional period. The estimate was based on provinciallevel newspaper reporting. It is a conservative estimate. A World Bank study on district-level newspapers in East Java and East Nusa Tenggara provinces for the years 2001–3 has shown that provincial newspapers seriously under-report conflict-related deaths, especially of the kind Varshney et al. label social violence (Barron and Sharpe 2005). However, the social violence statistics collected by this localized World Bank study counts crime deaths as conflict related, which may be a questionable assumption. Secessionist violence in East Timor, meanwhile, is thought to have caused between 1,400 and 1,500 deaths in 1999 (with 250,000 forcibly removed to West Timor) (CAVR 2005: Section 7.2 p. 245). The toll of secessionist violence in Aceh remains poorly documented, but has been estimated at around 7,200 from the end of the New Order until mid-2005.1 Figures for Papua are much lower, and have been neglected in this count. Taken together (and retaining the conservative UNSFIR estimates), a rough estimate for the toll of deadly violence associated with Indonesia’s transition of 1998 is almost 19,000 victims, of which over half died due to communal conflict and most of the remainder in secessionist violence. Displaced persons were another measure of the social impact of fighting. Near its peak in July 2002 about 1.3 million people were displaced from their homes due mainly to secessionist and communal disturbances (Norwegian Refugee Council 2002). The total ever displaced was much higher.

Writing only of the non-secessionist violence, and excluding social violence, the UNSFIR report drew the following conclusions:

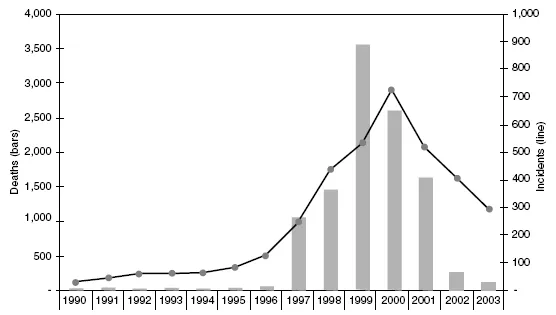

- Both the number of incidents and the number of deaths began to rise sharply in 1996, and peaked in 1999–2000, declining quickly after that (Varshney Panggabean and Tadjoeddin 2004: 25) (Figure 1.1). The peak thus came immediately after the collapse of the New Order, but violence had begun to rise about 2 years before it.

- Almost 90 per cent of those deaths were due to communal violence, both large-scale and localized. Of these deaths, 57 per cent were due to Christian– Muslim violence, 29 per cent anti-Madurese, and 13 per cent anti-Chinese (Varshney, Panggabean and Tadjoeddin 2004: 26). In other words, the largescale communal violence discussed in this book, namely Christian–Muslim and anti-Madurese, claimed by far the largest number of victims of any type of collective violence.

Figure 1.1 Deaths and incidents of non-secessionist collective violence in Indonesia, 1990–2003 (Varshney, Panggabean and Tadjoeddin 2004: 23).

Figure 1.1 Deaths and incidents of non-secessionist collective violence in Indonesia, 1990–2003 (Varshney, Panggabean and Tadjoeddin 2004: 23).

- The six provinces with the greatest violence were North Maluku (25 per cent of deaths), Maluku (that is, around Ambon, 18.3 per cent), West Kalimantan (13.6 per cent), Jakarta (11.8 per cent), Central Kalimantan (11.5 per cent), and Central Sulawesi (6.0 per cent) (Varshney, Panggabean and Tadjoeddin 2004: 30). Except for Jakarta, these were the locations of large-scale communal violence and form the focus of this book.

Anti-Chinese riots occurred during short burst of localized urban violence. It had been a recurring pattern throughout the New Order (Chirot and Reid 1997; Coppel 2002). Curiously, it disappeared along with the New Order. The last big event was the riot in Jakarta (and Solo) that brought down Suharto in May 1998. John Sidel (2001; in press) argued that the anti-Chinese riot was part of the ascendancy of a state-dependent Muslim elite, and that this type of riot came to a sudden halt when this group upped the ante during the post-1998 window of opportunity by engaging in straight religious competition. Anti-Chinese rioting is not further discussed in this book.

Communal violence thus claimed more lives than any other type of violence in this period – marginally more than secessionist violence, considerably more than ‘social violence’ (a grey category that shades into ‘ordinary’ criminality and that also surged at this time), much more than the localized single-location riots of the last years of the New Order, and very much more than the terrorist violence that so preoccupied the minds of post-9/11 commentators on Indonesia.

In terms of scale and duration, the only killings more bloody than this to have occurred in Indonesia were the anti-communist purges of 1965/66 (Cribb 1990). These spread more widely and killed half a million, but were worst in Java and Bali. The military organized them, but societal actors such as religious organizations also took part. A careful comparison of these two tragic affairs would be a worthwhile exercise. Underneath the clearly class-based ideology, which the post-1998 events lacked, 1965/66 involved ascriptive identities, mainly different experiences of Islam. Most importantly, the purges occurred at a moment of regime change, from the Sukarno to the Suharto presidencies, just as the episodes described in this book occurred during the transition from the Suharto to the reformasi era. Other episodes of collective violence in Indonesian history have also mixed political ideologies of nation or class with ethnic or religious identities – for example, the Darul Islam revolt of the 1950s (Dijk 1981), and of course the national revolution of 1945–50 (Reid 1974). What sets the post-New Order violence apart is that issues of class and the Indonesian nation virtually disappeared and fighting revolved almost exclusively around communal identities. This is what shocked the Indonesian public, which had always believed that being Indonesian had little to do with ethnicity or religion.

What are we to make of this communal violence? Indonesian public discourse revolved around the word ‘disintegrasi’. Calculating the relative frequency of this word at various times in my extensive collection of Indonesian electronic newspaper clippings, I discovered it leapt into the newsprint vocabulary in June 1998, within days of the massive riots that brought down President Suharto. It remained one of they key buzzwords of the period, only fading again towards the end of 2001. By that time most of the communal fighting had ended, and a new president had been elected, Megawati Sukarnoputri, who was widely seen as a leader who would restore order. The word suggested not just that the political compact called Indonesia was falling apart, but so were the ordinary social bonds among neighbours. Another word I traced was ‘Pancasila’, the rather banal semi-secular ideology often invoked by the New Order. Its frequency declined dramatically after 1998, suggesting a crisis in ‘official’ nationalism. Islamists had long condemned Suharto’s insistence on Pancasila, saying he was honouring the mere work of man at the expense of God’s revelation, but now their criticism was heard much more openly. Foreign experts on Indonesia echoed this feeling of breakdown in their writings (Dijk 2001; Kingsbury and Aveling 2003). Bertrand (2004) traced various kinds of collective violence in Indonesia to this crisis of identity. The readiness with which the word disintegration came to the minds of mainstream opinion makers suggested the powerful influence of an intellectual tradition that ascribed communal violence to the breakdown of social bonds. This so-called social strain and breakdown view saw rioting as a social pathology, as the aggressive, irrational behaviour of crowds driven by fear or frustration. Horowitz (2001: 7, 34–42) provides a useful review of the extensive literature based on such ideas, and reveals that he is an adherent of it to a great extent.

However, when I extended the counting exercise to other key words I found a second suggestive trend. This contradicted the view that things were falling apart, and instead reflected an alternative ideology of nationhood emerging at the local level. The term ‘putra daerah’, meaning ‘son of the soil’ and associated with ethnic localism, rose quickly after 1998. Likewise the term ‘adat’, meaning customary law. Both tended to decline again in the mainstream press after 2001. All this was a hint, easily confirmed by simply visiting the regions beyond Java, that what was seen as social breakdown in Jakarta might just be considered locally as a new beginning.2 The naive yet widespread view in Jakarta was that provincial Indonesians were traditional, religious and passive. But there was life and hope out there that expressed itself in a discourse Jakarta did not hear. Often it had a strongly localist, even xenophobic character and tolerance of different religions and ethnicities was thin. Violence was not far below the surface. But the point is that this was all positively political, and not just anomic. It was above all about reclaiming local government for the local community.

This led me to search for an alternative theoretical literature, one that made room for the political character of episodes of communal violence. I found some newer developments within social movements theory attractive in this regard. In some cruel sense, the violence was a part of normal politics. Shocking as this sounds, I believe the facts will largely bear it out.3

The editors of The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (Snow, Soule and Kriesi 2004b: 11) define the social movement, somewhat inelegantly but comprehensively, as

collectivities acting with some degree of organization and continuity outside of the institutional or organizational channels for the purpose of challenging or defending extant authority, whether it is institutionally or culturally based, in the group, organization, society, culture or world order of which they are a part.

This conceptualization involves five axes, and any movement must show at least three of them to be considered a social movement. These are

- collective, or joint, action;

- change-oriented goals or claims;

- some collective action that is extra- or non-institutional;

- some degree of organization;

- some temporal continuity.

As this book will illustrate, the Indonesian events had several of these characteristics. The crowds of people who attacked Madurese settlers in Kalimantan at various times, the massed fighters in the streets of Ambon or the villages of Central Sulawesi and North Maluku – these were certainly examples of collective action. Such crowd behaviour of course also had a place in the social strain literature, where it was considered irrational ‘collective behaviour’ (Gurr 1970; Smelser 1962; Turner and Killian 1987). But the Indonesian movements had other characteristics that made them look almost reasonable. They had clear goals. Some were tactical, such as expelling or defeating other collectivities seen as alien or dangerous, as well as (especially) getting their own members appointed to important local government positions. Others were strategic, such as demanding that immigrant groups submit to the cultural dominance of sons of the soil indigenous people, and being recognized by the central government as the legitimate powerholders in that area. No doubt these were xenophobic goals, but in the context of the militarized, rigidly top-down nature of the New Order they also represented change, the demand for a kind of democracy and local autonomy.

The extra-institutional nature of these movements’ collective action is one of their most interesting aspects. They used public spaces – the streets – for purposes for which these were not designed. Yet, like the demonstrations that flourished all over the country from 1998 onwards, they carried a clearly political agenda at a time when most institutions were in a state of complete disarray. Moreover, and this is a major point, the movements that engaged in communal violence were at least semi-organized. Much of what happened was ad hoc or got out of hand, but much else occurred by design. Indonesian discourse at the time pointed the finger at mysterious ‘provocateurs’ tasked by agencies in Jakarta to wreak havoc in remote places, but a little investigation revealed more convincing local institutional connections. Exactly how locally significant elites and their political parties, churches, mosque organizations, NGOs (non-government organizations) and pressure groups helped organize the crowds on the streets is the burden of this book. Temporal continuity, the fifth axis defining the social movement, is a bit more of a problem in the Indonesian cases we study. One of the curious features of these episodes is their evanescence. Many observers said they came from nowhere, and afterwards left no trace on the social landscape except segregated communities. But even here first impressions deceive. In fact ethnic organizations in Kalimantan had been working quietly for several years before the big outbreak. And religious organizations, with all their competitive exclusiveness, had been at the heart of every local community throughout the twentieth century.

In short, social movements theory, with its interest in organization and the link with normal politics in crisis mode, offered more fruitful perspectives on Indonesia’s episodes of communal violence than could be found in standard textbooks on collective violence such as those by Horowitz (1985, 2001). I have learned much from his...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Why now? Temporal contexts

- 3 Why here? The town beyond Java

- 4 Identity formation in West Kalimantan

- 5 Escalation in Poso

- 6 Mobilization in Ambon

- 7 Polarization in North Maluku

- 8 Actor constitution in Central Kalimantan

- 9 Concluding reflections

- Notes

- Bibliography