1 The urban context of love hotel districts

Walking through an area of the city populated with love hotels late on a Saturday evening, there is a sense of panic setting in as couples dart in and out of entrances in search of the last remaining rooms to stay for the night. On St Valentine’s Day1 and Christmas Eve, occasions in Japan when it is virtually an imperative to be with a loved one, this situation is accentuated still further. The clustering of love hotels effectively concentrates the available supply, facilitates browsing and stimulates spontaneous demand in a way that the stand-alone love hotel in the suburbs does not. Despite the existence and popularity of love hotel guides, most rooms are not booked in advance, which leads to the conclusion that roaming the streets is a customary part of the practice, and indeed the pleasure, of visiting an urban love hotel.

This chapter addresses the urban spatiality of the love hotel and accounts for particular aspects of its urban context, exploring the ways in which city dwellers participate in the spatial culture of a love hotel district, and analysing its key urban characteristics, which are evident at both the macro and the micro scales. My aim in this process is twofold: first, to characterise the love hotel district as part of a complex, changing and ambiguous network of urban spaces and experiences. Second, I aim to disrupt and problematise the Western tendency to emphasise the city’s physicality in arriving at an understanding of urban context, since ‘the Japanese do not comprehend urban space [through a grid pattern or a radiating network] but rather through collage or the empirical composition of symbols discontinuously scattered about.’2 This has led several Western observers to characterise Japanese urbanism as paradoxical, suggesting, for example, that ‘in Tokyo, the buildings are mostly Western, but their urban grid is not. The architectural style is visionary futuresque, but the urban structure remains medieval.’3 In order to escape this apparent ‘paradox,’ which is a product of a perceptual mismatch between expectation and reality on the part of a Western observer, it is necessary to reconceive the notion of urban form in a more gestural and participatory way; that is to say, not a tangible outcome of the design process, but as an aspect of the process itself.

The Japanese use the notion of kata to refer to the idea of form-as-process, a notion which applies to detailed patterns of movement, practised either solo or in pairs, and found in theatre forms such as kabuki, the performative ritual of the Japanese tea ceremony, and in martial arts. It is about learning time-based sequences of actions involving discipline and repetition, rather than a fixed arrangement or set of objects in space. In other words, kata embodies codified movement and gestural sequences, rather than a static navigational taxonomy or hierarchy. The Japanese love hotel, as an urban occurrence, precipitates its own kata, in that the actions of people frequenting love hotels were found to be entirely encoded and practised forms of behaviour. Structurally speaking, kata become synonymous with spatial practices only when they are conducted against the run of play; that is to say, when the rehearsed sequences are nevertheless unpredictable and have the effect of disrupting or countering conventional patterns of urban movement and inhabitation.

In analysing the perceptions of American city dwellers in the late 1950s, Kevin Lynch found that their ‘mental maps’ could be schematised cognitively into five distinct formations, namely path, edge, node, district and landmark. While these were codified as the constituent elements involved in perceptions of physical urban form in Lynch’s book Image of the City, I want to use them here in the manner of kata, in such a way as to infer from Lynch’s fixed structural hierarchy an approach that is more appropriate to the examination of a non-Western context. Fredric Jameson valorised Lynch’s work in terms of introducing cognitive mapping to urban design theory, but argued that it is problematic because it lacks any sense of political agency or historical process. This lack makes it all the more pertinent to the Japanese urban context, however, where both such dimensions have also been found to be absent.

Unpacking a Western cognitive model by bringing it into contact with a Japanese urban context will reveal its limits and qualify its parameters in a new way. The structure of this chapter works through path, edge, node, district and landmark in sequence, and shows that, in Japanese urbanism, they do not form a unity of parts as Lynch envisaged. Rather, they may be seen to configure a makeshift and mobile reading of place. Jameson notes in relation to Lynch’s work,

there comes into being, then, a situation in which we can say that if individual experience is authentic, then it cannot be true; and that if a scientific or cognitive model of the same content is true, then it escapes individual experience.4

In examining the urban context of the love hotel, I am interested in neither the truth of the experience nor the model, but in the interplay between the two.

Path

An important distinction that is made in terms of Japanese urban street life is between omotedōri and uradōri,5 which is to say between the main public thoroughfares and the more private back streets. Arie Graafland comments upon the fact that ‘behind and under the new large-scale urban buildings the fine-meshed network of another Tokyo continues to exist.’6 Urban historian Hidenobu Jinnai claims that the European city is founded on a ‘piazza society,’ where the public realm is largely synonymous with civic focal or gathering points of historical significance, whereas the Japanese city is informed by the logic of ‘backstreet society,’ in the sense that ‘rank-and-file urban society in Edo was sprinkled with numerous minute backstreet open spaces.’7 Barrie Shelton has also commented: ‘big streets in Japan are not high points of visual delight,’8 and that ‘the contrast between the big buildings on the big streets and the small-scale intimacy of the lanes can be astounding. Though a stone’s throw from the big streets, the lane can seem very distant in spirit and character.’9

It is precisely these lanes and back streets which clusters of love hotels occupy: despite the fact that they depend on the critical mass of the urban populace to supply sufficient custom to keep their room occupancy rates up, they are nevertheless not located on the omotedōri,10 and instead may be found a few streets back in the uradōri parts (see Figure 1.1). This is in part due to the vagaries of tenure and urban land use in Japan, where planning policy, particularly in Tokyo, has tended to neglect back street areas and has allowed unplanned development to spring up. André Sorensen’s work, The Making of Urban Japan, reveals how it was the urban commoners who inhabited the inner urban blocks or urachi, and in the eighteenth century access to the interior of these blocks was formed by a series of shinmichi, narrow streets.11 Typically these overcrowded areas were occupied by nagaya, long and cramped rows of single-storey accommodation. By contrast, many of the omotedōri are the product of the 1954 Land Readjustment Law, which contained provisions to compulsorily purchase land in order to build new urban infrastructure – enabling the major avenues and boulevards in Tokyo to be realised.12

Moving along a path from the omotedōri street atmosphere to a uradōri one is a qualitative shift in terms of the city’s psychogeography: the streets typically become less formal and upmarket, instead becoming progressively darker, more intimate and more secretive. The scale of the buildings reduces, the width of the street constricts, there are few traffic-lights, and limited vehicular movements casually traverse intersections. Here the bicycle and the small delivery lorry are the main vehicles present, and, although they are not designated as such, the predominant movement found on these back streets is pedestrian. In these narrow streets containing myriad entertainment functions, particularly those lined with love hotels, the pace of the city decelerates to a leisurely stroll, punctuated by glimpses into intriguing interior worlds.

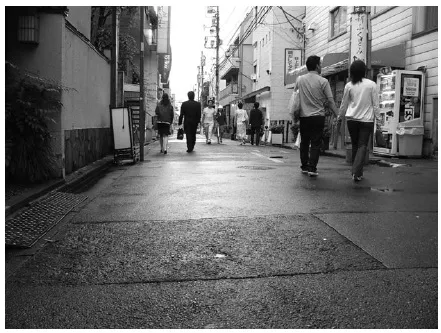

The nature of movement in this context must be understood as something relatively new in the context of Japanese cities, for as Donald Richie points out, ‘Edo had no promenades,’13 and hence no paths that were dedicated to strolling. The streets were too narrow at that time to provide pavements for pedestrians, and Richie reminds us that it was not until the Meiji and Taisho eras that it became popular to stroll along the wide streets lined with department stores full of Western consumer delights in the newly rebuilt Ginza. Here, groups of modern men or women (moba and moga) would stroll, browse and take afternoon tea or drink coffee in a sophisticated European-style café, a spatial practice known as ginbura. Although men and women are also strolling and browsing in a love hotel district, this is quite a different kind of spatial practice from ginbura, being a more intensely private experience and one which entails walking arm in arm as a couple, rather than alone or in single-sex groupings (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 Typical narrow backstreet (uradōri) of love hotels, Uguisudani, Tokyo.

Figure 1.2 Couples walking up Love Hotel Hill, Shibuya, Tokyo.

The nightlife and gaiety of Ginza in the Taisho era was gradually displaced to Shinjuku in the west of Tokyo, and it is here that the character of a particular back street district found in Shinjuku’s Kabukichō still offers clues as to how the particular atmosphere of the love hotel street developed: Golden Gai, which many Japanese would say typifies the old Tokyo, is described by Donald Richie as:

A small crammed warren of questionable bars and disreputable looking drinking stalls with rooms upstairs. Though developers have been at work for years, the owners are hardy and have not as yet agreed to being evicted. Walking these narrow lanes with the smell of sake and toasted squid in the air, amid the calls of women and the lighted lanterns of their shops, it is possible to imagine the Shinjuku of long ago.14

Golden Gai is easy to miss, as the appearance of this tiny microcosm from the streets approaching it is particularly unprepossessing, and it takes courage and familiarity (not to say initiation) to penetrate the tatty but well-preserved enclave. All around Golden Gai there are signs prohibiting the use of camcorders and cameras, as it is a favourite location for filmmakers and attracts a great deal of curiosity, indicating that there is now a nostalgic impulse towards capturing and aestheticising such a uniquely Japanese urban environment. Behind every door adorned with peeling paint and old flyers advertising events and services, each nomiya or bar is no more than a two-storey makeshift hut, with a tiny antiquated room downstairs containing four or five bar stools, and personal bottles of whisky kept on shelves for regular customers. The rooms above are no longer in use, but were once proverbial ‘knocking shops,’ which clients could repair to with a woman of their choice after a session of hard, convivial drinking. The path from drinking (nomu) to buying women (kau) here is a short vertical manoeuvre, and the context is one of total informality and simple, straightforward access to creature comforts. Over time, as Stuart Braun describes, the demi-monde emphasis changed, and ‘the upper floors of these coarse wooden and tin sheds were transformed into bars, and by the 1960s, over 200 nomiya had sprung up around the maze of laneways,’15 which became the favourite haunts of Tokyo’s leading cultural elite and political refuseniks.

By the 1990s, half of these bars had been lost to redevelopment initiatives, and in the streets adjacent to Golden Gai clusters of love hotels had sprung up, which according to Braun are ‘given to accommodating strays from the 100- odd drinking dens that make up the Golden Gai.’16 In the process of expanding and proliferating the nocturnal activities of Golden Gai into their modern-day equivalents, the journey from a drink after work to a night of love-making has become more attenuated, and can now be seen to occupy, both spatially and temporally, distinct phases. So much so that the path of a romantic date (deito) is now explicitly constructed as a narrativised itinerary analogous to a good meal in Japan’s growing number of ‘dating’ magazines, which contain articles recommending different date ‘courses’ for a drive, a viewing spot, a restaurant, a visit to a place of interest and so on. In such articles the love hotel is characterised as the final course, a dessert or postre to the evening’s entertainment, clearly integrated into the proceedings as its inevitable and premeditated conclusion.

What has been preserved of Golden Gai’s quintessential streetscape in the process of moving from lustful spontaneity to romantic premeditation are the qualities associated with its spatial intimacy, while all of the social intimacy and gregariousness has been rinsed out. This renders a contemporary street of love hotels one in which couples experience the oxymoron of total urban anonymity in a local, neighbourhood setting: the ambience combines an image of discretion with the opportunity for indiscretion. Here, the love hotel customer’s passage begins by publicly walking down the street, often in the middle of the empty road, carrying briefcases or bags of shopping, then shifts sideways with a knights-move to depart from their everyday life into a displaced and temporary form of existence. This gestural form, or kata, is an aleatory drifting, which the convoluted entrances and exits to the love hotels themselves intensify. The sense of drifting is further accentuated by the mediating and disorientating effect of the signage in such a streetscape, which has ‘never added up to a definitive or rigid order.’17 Signs, like the entrances, act as filters, designed to solicit custom from only those who can navigate the flows of space and information in search of a room.

Traditionally, the Japanese street is treated as an extension of the interior of the dwelling, with plants and personal belongings placed right on the edge of the paved surface, prefacing the space of the interior. This zone is known as the engawa, and is what Kisho Kurokawa calls ‘grey space,’ creating a zone of public–privateness that is ambiguous and shared between street and interior. The etymology of the prefix en in the word engawa means forming a bond, affinity or relationship. As a spatial concept, it is therefore less about separating than about uniting two distinct spatial conditions. In terms of the love hotel, this space is an important precedent for a love hotel’s particular mediation of a paththreshold condition, where the fabricating of a human bond is the logical and implied outcome of the passage from street to interior. Moreover, the transition in the path from street to interior carries an additional load, since it is not simply a public–private threshold to be crossed, but one which entails a transgressive modal shift in societal terms: the couple entering are embarking upon a journey, a line of flight, which takes them from the prosaic, normalised context of their daily lives to something and somewhere else, and the prolongation of this passage from one to the other is a process of othering. Kurakawa also discusses a finer grain of intermediary spaces, namely kansho, which were even smaller alleyways and backlots between buildings themselves, creating a further layer of spatial mediatio...