eBook - ePub

Doing Justice without the State

The Afikpo (Ehugbo) Nigeria Model

Ogbonnaya Oko Elechi

This is a test

Share book

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Doing Justice without the State

The Afikpo (Ehugbo) Nigeria Model

Ogbonnaya Oko Elechi

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This study examines the principles and practices of the Afikpo (Eugbo) Nigeria indigenous justice system in contemporary times. Like most African societies, the Afikpo indigenous justice system employs restorative, transformative and communitarian principles in conflict resolution. This book describes the processes of community empowerment, participatory justice system and how regular institutions of society that provide education, social and economic support are also effective in early intervention in disputes and prevention of conflicts.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Doing Justice without the State an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Doing Justice without the State by Ogbonnaya Oko Elechi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Derecho & Derecho internacional. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction

“Justice cannot be for one side alone, but must be for both”

—Eleanor Roosevelt

“Judgement is not given after hearing one side”

—Igbo proverb

Afikpo is the second biggest city in Ebonyi state, which is situated in South Eastern Nigeria. In 1991, the population of Afikpo was estimated to be 110,000. The administrative headquarters of Afikpo North Local Government Area, prior to colonialism, Afikpo, like most societies in Africa, had a well-defined system of political and social control. This like other aspects of African, democratic socio-political practices, was subjugated by the British colonial authorities when they instituted a central government for Nigeria. Afikpo peoples’ resistance to colonial rule and the emergent colonial political and judicial institutions partly explains the survival, and the increasing popularity, of the Afikpo traditional1 conflict resolution system.

The principles and practices of the Afikpo indigenous justice system is examined from a restorative, transformative and communitarian paradigm. The thrust of this inquiry is on the traditional political and social institutions and their application in recent years. These institutions function as channels for conflict resolution and deviant controls. Emphasis of the study is on the processes and principles of justice making, rather than on the outcomes of the system’s response to crime and victimization. The basis of the Igbo peoples’ egalitarian world outlook and ability to constantly adapt to changes is inquired into. The Afikpo indigenous institutions of social control are also effective and widely respected major agents of socialization2 and resocialization, providing teaching and healing support to both victims and offenders, and their families. Teaching is also intended to transform the offender from a non-conforming person to a conforming individual to protect the community. Other objectives of the Igbo socialization and resocialization processes are to inculcate the values of moral uprightness, industry and discipline in the Igbo person (Iro 1985). The Afikpo community conflict resolution system commands nearly total acceptance and participation, and is, widely viewed as legitimate by the community. Further, attempts are made to explain how and why these institutions co-exist with State regulated non-indigenous institutions of conflict resolution.

The Afikpo traditional system of conflict resolution functions essentially as an alternative system of conflict resolution. Nigeria, as part of its colonial heritage, has instituted modern institutions of conflict resolution. The modern Nigerian system of conflict resolution, similar to western juridical systems, makes use of the police, courts, prisons and other governmental agencies of social control. No claim is made that the findings of the research can be generalized beyond the Afikpo community. The nature of the Afikpo resolution system is unique. As a result, this exploratory study tends to fit into what is commonly known within the qualitative research methods as “intrinsic research.” Stake defines intrinsic research as a

… specific, unique, bounded system … undertaken because one wants better understanding of this particular case. It is not undertaken primarily because the case represents other cases or because it illustrates a particular trait or problem, but because, in all its particularity and ordinariness, this case is of interest (in Denzin/Lincoln (ed.) 1994: 237).

This book derives from my Ph.D. dissertation, which foundation was laid during my undergraduate studies at the University of Oslo. My academic interest in restorative justice started after I heard Professor Nils Christie speak about the subject in one of the Oslo University Institute of Criminology’s seminars. Further readings of Nils Christie’s works on restorative justice re-affirmed my observation that similar principles guided the Afikpo traditional system of conflict resolution. I was immediately fascinated with the logic of restorative justice, particularly because it seemed to provide the answer to me for why the Nigerian State Criminal Justice System was ineffective and largely ignored by the Afikpo people. The Afikpo traditional system of conflict resolution was chosen for this study because I am familiar with the system and culture of the community. I was born and raised in Afikpo and participated in some of the cultural activities of the community as a child. With time, my involvement in the social and political activities of the community was confined to Church and School activities. The Church and School authorities discouraged us from getting involved in the cultural activities of the community. The indigenous system was believed heathenish and a negative influence on Afikpo youth at the time.

BRIEF HISTORY OF NIGERIA

Nigeria is located in Western Africa, and the geographic coordinates are 10 00 N, 8 00 E. Nigeria is bounded on the West by the Republic of Benin, on the North by Niger and Chad, Cameroon on the East, and the Atlantic Ocean in the South. The political history of modern Nigeria began in 1914 when Lord Lugard amalgamated the protectorates of Northern and Southern Nigeria under British rule. In 1954, the first fully federal constitution was drawn-up, initiating the process to self rule. In 1956 the British colonial authorities granted Western and Eastern Nigeria self-governing status. This self-governing status was accorded to Northern Nigeria in 1959.

Nigeria achieved its full political independence from Britain in 1960. Nigeria promptly adopted a federal constitution, with three semi-autonomous regions, namely the Northern, Western, and Eastern regions, which were dominated by the Hausa/Fulani, the Yoruba, and the Igbo ethnic groups respectively. The three regions and the federal government each operated the Westminster style parliamentary system.

Presently, the geo-political structure of the Federal Republic of Nigeria is made up of 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja3. According to the 2005 population estimate, the total Nigerian population is 128,771,988. The age structure of the population according to data from the World Factbook on Nigeria is as follows:

0–14 years—42.3% (male 27,466,766/female 27,045,092);

15–64 years—54.6% (male 35,770,593/female 34,559,414);

65 years and above—3.1% (male 1,874,157/female 2,055,966).

15–64 years—54.6% (male 35,770,593/female 34,559,414);

65 years and above—3.1% (male 1,874,157/female 2,055,966).

The population growth rate is 2.37%; the birth rate is 40.65 births per 1,000 population; the death rate is 17.18 deaths per 1,000 population, according to the 2005 population estimates. Based on the 2005 estimates, the infant mortality rate is 98.8 deaths per 1,000 live births. The life expectancy rate of the entire population is 46.74 years, with males averaging 46.21 years, females 47.29 years.

Nigeria is the most populous African Nation, and potentially one of the wealthiest countries of black Africa. Nigeria is blessed with skilled human and abundant natural resources. Nigeria is also considered the most ethnically diverse society in the world with about 252 identifiable ethnic groups. More than ninety-nine percent of the northern population, are Moslems, who account for more than 50 percent of the total Nigerian population. Christianity is dominant in the South, accounting for about 35 per cent of the country’s total population, while adherents of African religion make up the balance.

The Nigerian economy is heavily dependent on oil earnings. Oil production, at about 2 million barrels a day (mn b/d.), account for over 90% of total Nigeria’s export earnings. However, oil accounts for only 13.6% of total GDP. This is because the economy is still based on a traditional agricultural and trading economy. Nigeria, once a large net exporter of food, now imports food, owing to the failure of the largely subsistence agricultural sector to keep up with rapid population growth. The dominance of the oil sector in the economy led to the neglect and decline of the agricultural sector.

The area of Nigeria is 923,770 sq.km, with the land mass totaling 910,770 sq.km, and water 13,000 sq.km. About 33% of Nigerian land is arable. The climate in Nigeria varies from equatorial in the south, tropical in the center, to arid in the north. The terrain also varies from southern lowlands, with hills and plateaus prevalent in the center of the country. The southeastern part of Nigeria is mountainous, with flat land in the north.

The literacy rate of Nigeria’s population of 15 years and above is 6 8%. The literacy rate of males is 75.7% and that of females is 60.6%, according to the 2003 estimates.

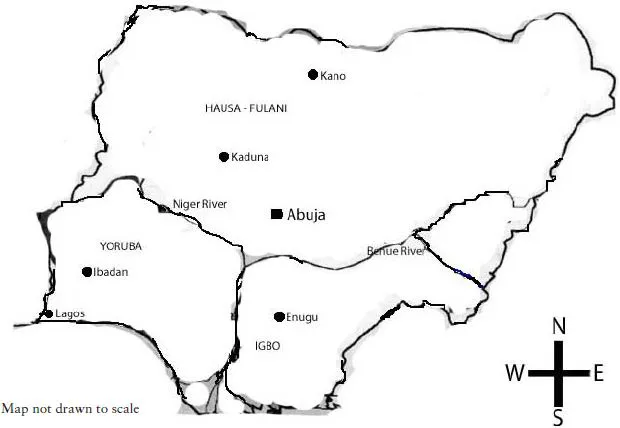

Figure 1.1. Map of Nigeria Showing the Three Major Ethnic Groups – Namely – the Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba and the Igbo.

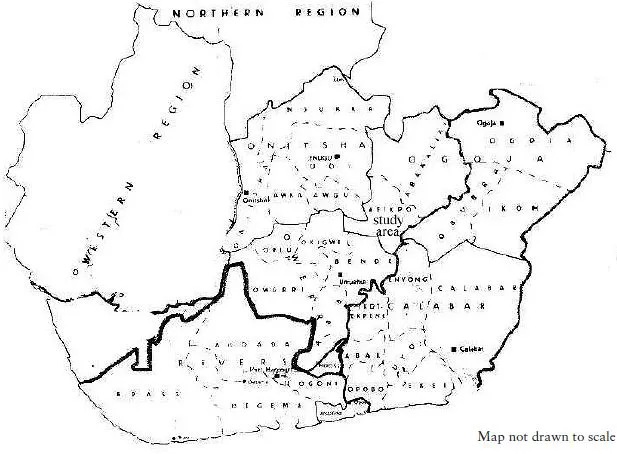

Figure 2.1. Map of South East Nigeria Showing Afikpo Town – the Study Area.

OBJECTIVES OF STUDY

The thrust of the study is the examination of the Afikpo indigenous system of conflict resolution in contemporary times. The justice system derives from Afikpo peoples’ culture.4 Inquiry into some aspects of the peoples’ culture was undertaken with a view to understanding the basis of the justice system. The culture of a people is central to its world outlook. The culture of a group, according to Roberts (1979: 39) “reflects the extent to which its people will identify with individualist or collectivist values. There is a link between the dominant social values in a society and the likely responses to conflict. This includes the amount of quarreling that is acceptable, the way disputants approach an altercation, as well as the way that third parties are expected to intervene.” Included in the inquiry was a critical evaluation and assessment of the traditional political institutions and social organizations that function as channels for peace-making and social controls. The study emphasized the process and principles of conflict resolution.

One major objective of the study comes from my experience growing up in Nigeria where a vast majority of the people find the type of justice offered by the state courts inappropriate for the resolution of their disputes. There was always an acrimonious relationship between my community and agents of the criminal justice system. For example, it is an offense against the community to report a crime or take a conflict to the state courts or police, until the community had mediated on the matter. A goal of my research has been to address the question: Why have the African indigenous institutions of social control remained relevant in the affairs of the people despite the dominant position of African states in social control? Specifically, my research goal was to discover why the Afikpo system enjoys such wide approval and seeming legitimacy among the Afikpo people. The system’s popularity seems to cut across economic and social class boundaries, even among non-indigenous people living in Afikpo. Again, many questions help to understand the continued existence and popularity of the Afikpo indigenous system of conflict resolution. What is the system’s concept of justice? Is the system free of the charges of “nothing works,” “disguised coercion,” and “net widening” associated with other alternative systems of conflict resolution? Why is the government-sponsored alternative conflict resolution unpopular?

Another major objective of the study is to examine major Afikpo traditional institutions, both as agents of social control and resocialization from a restorative, transformative and communitarian justice perspective. Further, inquiries are made into how the community resolution system responds to certain norm violations and conflict in the community. Again, the position and roles of victims and offenders in the system are examined.

It is hoped that findings from this research will inform future Nigerian criminal justice policies. Further, it is difficult not to assume an advocacy role and use one’s writings to counter Western views of African justice system as repressive and simplistic, and that African indigenous justice systems are not capable of respecting the rights of women, suspects and other litigants. Furthermore, with the current worldwide interest in restorative justice, it is important to trace restorative justice to its roots in indigenous traditions in Africa, Asia and Native American cultures.

WHAT IS RESTORATIVE JUSTICE?

There is no agreement on what constitutes restorative justice principles and practices. Some refer to restorative justice programs as transformative justice, peacemaking criminology, relational justice, or community justice. The different names reflect the varied visions of their proponents. Marshall (1996) believes we are involved in a restorative justice process when “victims, offenders and other stakeholders meet face-to-face to resolve their conflicts” (Bazemore and Walgrave 1999: 47). Marshall views restorative justice as a diversion, hence only certain cases are suitable for the process. Serious violent cases are not suitable for restorative justice processes. Other restorative justice advocates view the system as involving “a variety of processes or procedures, including those that occur within the formal justice system, aimed at reaching an outcome focused on repair” (Bazemore and Walgrave 1999:47). Others argue that restorative justice must take place in an informal setting and participation must be voluntary. Restorative justice is a negotiative process, where the victim, the offender and the community are primary stake-holders. Adherents of this perspective observe it is possible to transform the state courts to operate in restorative fashion. Participation does not have to be voluntary for participants may be coerced into involvement in the restorative process. Coercion may be applied to achieve reparation to victims or for offenders to do community service. However, “what makes these obligations and processes ‘restorative,’ rather than retributive or rehabilitative, is the intent with which they are imposed and also the outcome sought by decision-makers” (Packer 1968 as cited in Bazemore and Walgrave 1999:47). (Italics in original).

The diverse outlooks notwithstanding, what is commonplace is a disenchantment with the current state-administered retributive justice system and the need for alternative ways of responding to conflict, crime and victimization. The criminal justice system is seen as authoritarian, and alienates victims, offenders and the community who are primary stake-holders in the conflict (Christie 1977). Retributive justice systems are considered rigid and obsessed with punishment. Restorative justice system advocates support increased victim and community involvement in sentencing processes and general response to crime. As Marshall (1996:37) points out, restorative justice is defined as a “process whereby the parties with a stake in a particular offense come together to resolve collectively how to deal with the aftermath of the offense and its implications for the future” (cited in Bazemore and Walgrave 1999:47).

As an emerging paradigm, restorative justice views and responds to wrong-doing differently from retributive justice systems. Rather than view crime as an act against the state, a violation of law, an abstract concept, for which the offender is accountable to the state, it views crime as a violation against an individual or group of individuals, and interpersonal relationships. The primary victims are those directly affected by the offense, and the secondary victims are the family members of victims, offenders, witnesses and members of the affected community. As such, accountability is primarily to the victims, and secondarily to the state. Restorative justice represents a paradigmatic shift, which Pranis, et al (2003:10) state are:

1. from coercion to healing;

2. from solely individual to individual and collective accountability;

3. from primary dependence on the state to greater self-reliance within the community; and

4. from justice as “getting even” to justice as “getting well.”

Further, distinctions are made between the retributive justice and restorative justice, by focusing on their peculiar processes and objectives. Walgrave (1994), as cited in Weitekamp (1999:75), notes that a retributive justice system responds to crime “within a context of state power.” Their focus is on the offense, and the state is empowered to inflict punishment and seek just dessert, while the victim is generally neglected. However, it is noted that the retributive justice system embodies sometimes certain traces of restorative justice objectives. Nevertheless, restoration of the victim or the community is not part of the major goals of retributive justice. Rehabilitative response as an aspect of retributive justice, contends Walgrave (1994) “takes place in the societal context of a welfare state, focuses on the offender, provides treatment to him or her, seeks conforming behavior and ignores the victim as well” (as cited in Weitekamp 1999:75). On the other hand, restorative justice empowers the community and other primary stake-holders in the conflict. Its goal includes repairing or restoring losses, the satisfaction of the parties to the conflict, with the victim seen as central to the whole justice process.

Restorative justice is incomplete, according to Bazemore and Walgrave (1999), if it does not seek to repair the harm caused by the victimization. Essentially, restorative justice must seek to restore the following according to Braithwaite and Parker (1999:106).

• Restore property loss

• Restore injury

• Restore sense of security

• Restore dignity

• Restore sense of empowerment

• Restore deliberative democracy

• Restore harmony based on feeling that justice has been done

• Restore social support.”

Restorative justice has a focus on rest...