- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Medicinal Plants of Asia and the Pacific

About this book

Drawing on the author's extensive personal experience, Medicinal Plants of Asia and the Pacific provides comprehensive coverage of the medicinal plants of the region. Describing more than 300 compounds, the book discusses every important class of natural products while highlighting cutting-edge research and recent developments. With its broa

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Medicinal Plants of Asia and the Pacific by Christophe Wiart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Medicina alternativa e complementare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

When writing this introduction I could not help but think of Ethnotherapies in the Cycle of Life: Fading, Being and Becoming, edited by Christine E. Gottschalk-Batschkus and Joy C. Green. The feeling I had after reading this beautiful book was somewhat uneasy as it prompted with some embarrassment the utopian idea that the eradication of human illnesses will only be achieved when shamanism, traditional medicines, and science work side by side. In other words, traditional medicines and shamanism supported by strict scientific research might give birth to a hybrid concept that could put an end to existing human diseases.

Shall we see professors of medicine and shamans working together? In all probability, “yes,” because we have no alternative. The logic of biological systems never allows a complete victory over anything, including a victory of drugs against diseases. We all know that at this moment we are right in the middle of a furious battle for survival. Not so long ago, giving birth and coughing were often followed by death. Certainly, we cannot deny that antibiotics have greatly improved the treatment of bacterial infections. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, we have to admit that the war with bacteria is far from won because resistance is common. The same can be said for viruses, parasites, and cancer cells. Many people also need sleeping pills and antidepressants to get through the day or sleep at night because of our stressful lifestyles, and we are likely to be blighted further by the emergence of massive epidemics or new diseases, since Mother Nature is very creative.

What is left of traditional systems of medicines? With the daily depletion of acres of rain forests, not much is left, but there is still enough to cover the health needs of most of the world’s population. The last 50 years were the theater for the first great pharmaceutical discoveries and, at the same time, saw the progressive disappearance of traditional knowledge. Shamans and other healers came to be regarded as charlatans and were abandoned even by their own peoples who preferred taking aspirin instead of drinking bitter decoctions of roots. This increasing lack of interest in natural remedies has to be accepted as inevitable given the potency of modern pharmacochemistry.

Does this mean an end for even the vestiges of shamanism, rituals, and traditional medicines? How can the past resist the continuing attack of modern medicine with its accusations of placebo effects, clinical disappointments, and lack of scientific evidence? Who can tell? But, based on past evidence, there is also the possibility of finding new plants that can “hit the jackpot” of therapeutic effectiveness. If the Amazon and to a lesser extent Africa have seen the disappearance of traditional medicine and medicinal flora, the Pacific Rim still boasts the richest pharmacopoeia of traditional medicines and medicinal plants; it can be regarded as the very last gift of Mother Nature in the cause of human health. The mass of bioactive molecules represented by the medicinal flora of the Pacific Rim is formidable indeed. In this book I have chosen to present 173 of these species. The plant choices were guided by the exciting fact that there have been few studies of these species for their pharmacological effect. Readers are invited to pursue further research with the possibility of drug discovery.

The 173 medicinal plants described in this book are classified by families, starting from the most primitive ones and moving onto more recent discoveries. A pharmacological or ethnological classification would have been possible, but I prefer the botanical one as it allows a broad logical view of the topic with chemotaxonomical connections. The medicinal plants presented in this book are classified according to their botanical properties in the philosophical tradition of de Candolle, Bentham, Hooker, Hallier, Bessey, Cronquist, Takhtajan, and Zimmerman, which is my favorite.

The approach used in this book is strictly scientific, given that I am a scientist and not a shaman. Perhaps shamanism and alternative practices will become included in the curricula of schools of medicine, but for the moment this is not the case. Plants are described here as accurately as possible, and I hope that their traditional uses are clearly presented. The pharmacotoxicological substantiation of these uses in the light of chemotaxonomy is also discussed. I have produced a carefully drawn figure for each plant and noted its geographic location, which allows for quick field recognition for further investigation. I have tried to use all the available data obtained from personal field collections, ethnopharmacological investigations, and available published pharmacochemical evidence. At the same time, I have attempted to provide some ideas and comments on possible research development. I hope that this book will contribute to the discovery of drugs from these plants.

The pharmacological study of medicinal plants of the Pacific Rim has only recently begun to be useful to researchers and drug manufacturers who see in it a source of new wealth. A field of more than 6000 species of flowering plants is awaiting pharmacological exploration. One reason for this lack of knowledge is the fact that most of these plants grow in rain forests, hence the difficulties in collecting them from remote areas where modern infrastructures are not available. Let us hope that the future will see more successful business and scientific ventures between developing countries and developed ones with fair distribution of benefits, including those to villagers and healers who may have helped in finding “jackpot” plants.

The first 24 species of medicinal plants described are part of the Magnoliidae, which are often confined to primary tropical rain forests. Their neurological profile is due to the fact that neuroactive alkaloids are evenly distributed throughout the subclasses: Annonaceae, Myristicaceae, Lauraceae, Piperaceae, Aristolochiaceae, and Menispermaceae. These are often trees or woody climbers that can provide remedies for the treatment of abdominal pains, spasms, putrefaction of wounds, and inflammation, as well as curares for arrow poisons and medical derivatives.

A commonplace but interesting feature of these plants is their ability to elaborate isoquinoline alkaloids (benzylisoquinolines or aporphines), phenylpropanoids and essential oils, piperidine alkaloids phenylpropanoids, and nitrophenanthrene alkaloids. Alkaloids are of particular interest here as they may hold some potential as sources of anticancer agents, antibiotics, antidepressants, and agents for treating Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

The evidence presented so far clearly demonstrates that members of the family Annonaceae elaborate a surprisingly broad array of secondary metabolites that inhibit cancerous cells, including acetogenins, styryl-lactones, and isoquinoline alkaloids. Aristolochiaceae have attracted much interest in the study of inflammation, given their content of aristolochic acid and derivatives that inhibit phospholipase A2. Other antiinflammatory principles may be found in the Myristicaceae, which produce a series of unusual phenylacylphenols. The evidence in favor of dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid)-ergic alkaloids in the Magnoliidae is strong and it seems likely that anxiolytic or antidepressant agents of clinical value might be characterized from this taxon. Alkaloids of the Magnoliidae are often planar and intercalate with DNA, hence their anticancer properties. The Annonaceae and Lauraceae families abound with aporphinoid alkaloid topoisomerase inhibitors.

The next 42 species are members of the Dilleniidae, Elaeocarpaceae, Bombacaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Ebenaceae, Myrsinaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Passifloraceae, and Capparaceae. Most of these are used as antiinflammatory, counterirritant, or antiseptic agents in gynecological disorders. In comparison to the former group, the medicinal plants here abound with saponins which are cytotoxic, antiseptic, antiinflammatory, diuretic, and mucolytic; they elaborate a broad array of chemicals—cytotoxic oligostilbenes, quinones (Nepenthales), isothiocyanates (Capparales), cucurbitacins (Malvales and Violales), and naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids (Violales). Myrsinaceae produce an unusual series of benzoquinones, which have displayed a surprising number of pharmacological activities, ranging from inhibition of pulmonary metastasis and tumor growth to inhibition of lipooxygenase. Ebenaceae, particularly the Diospyros species, have attracted a great deal of interest for their dimers and oligomers of naphthoquinones which are antibacterial, antiviral, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and cytotoxic via direct binding of topoisomerase. Note that Polygonaceae, Myrinaceae, and Ebenaceae are quinone producing families. Myrinaceae, Ebenaceae, and Sapinaceae abound with saponins.

Elaeocarpaceae elaborate an interesting series of indolizidine alkaloids derived from ornithine and cucurbitacins. Cucurbitacins are oxygenated steroids with chemotherapeutic potential, which have so far been found in the Cucurbitaceae, Datiscaceae, and Begoniaceae families. Capparaceae use isothiocyanates (mustard oils) as a chemical defense; they can make a counterirritant remedy. Isothiocyanates are interesting because they are cytotoxic, antimicrobial, and irritating, hence the use of Capparales to make counterirritant remedies. Medicinal Flacourtiaceae accumulate a series of unusual cyclopentanic fatty acids with potent activity against Mycobacterium leprae, hence their use to treat leprosy.

There are 68 species of medicinal plants belonging to the Rosidae, of which the families Connaraceae, Rosaceae, Anisophylleaceae, Thymeleaceae, Melastomataceae, Rhizophoraceae, Olacaceae, Icacinaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Sapindaceae, Anacardiaceae, Simaroubaceae, Meliaceae, and Rutaceae are presented in this book. Rosidae are in general tanniferous and provide astringent remedies that are used to check bleeding, to stop diarrhea and dysentery, to heal and inhibit the formation of pus, to cool, and to lower blood pressure. Tannins, which are often removed in extraction processes since they provide false positive results in high-throughput screenings, hold enormous pharmacological potential. With regard to the antineoplastic potential of Euphorbiaceae, most of the evidence that has emerged from the last 30 years lends support to the fact that they represent a vast reservoir of cytotoxic agents; one may reasonably expect the isolation of original anticancer drugs from this family if enough work is done.

Other principles of interest are essential oils, and oxygenated triterpenes in the Simaroubaceae, Meliaceae, and Rutaceae. The latter is of particular interest as a source of agents for chemotherapy. Rutaceae have attracted a great deal of interest for their ability to elaborate a series of cytotoxic benzo[c]phenanthridine and acid in alkaloids, a number of derivatives of which are of value in the treatment of acute leukemia in adults and malignant lymphomas, refractory to conventional therapy.

The last group of medicinal plants described encompasses Loganiaceae, Gentianaceae, Apocynaceae, Asclepiadaceae, Solanaceae, and Verbenaceae, making a total of 37 medicinal plants that are often used as analgesics, antipyretics, antiinflammatories, and to make poisons. These are plants with tubular flowers grouped in the Asteridae. The chemical weapons found in this subclass are mostly monoterpenoid indole alkaloids, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, iridoid glycosides, phenylethanoid glycosides, cardiotoxic glycosides, naphthoquinones, diterpenes, and sesquiterpenes. The most common medicinal properties of these plants are those of alkaloids, saponins, and iridoids. Alkaloids of the Apocynaceae are historically of value in fighting cancer, but many other molecules await discovery.

CHAPTER 2

Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Annonaceae

2.1 GENERAL CONCEPT

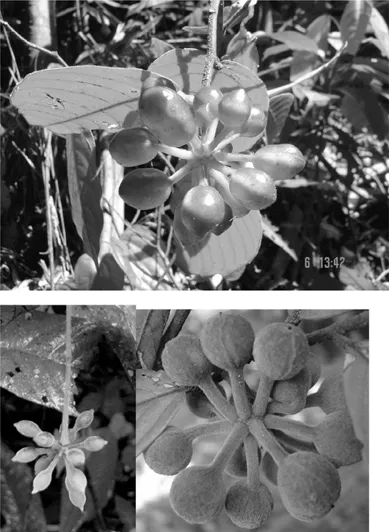

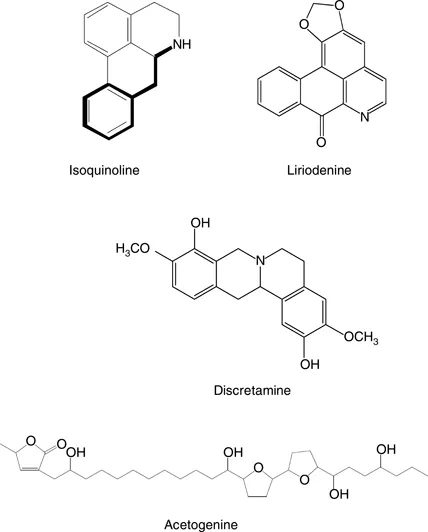

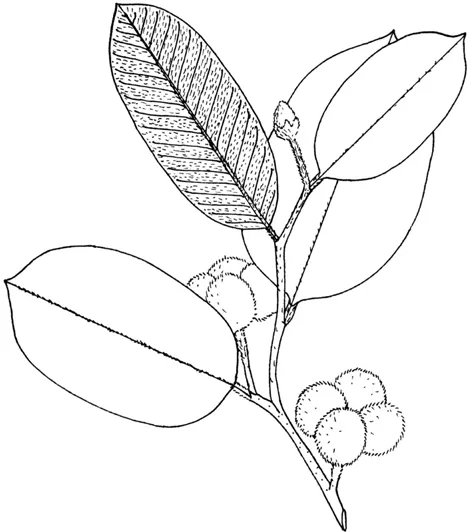

One of the most exciting families of medicinal plants to start with when prospecting the flora of the Asia–Pacific for drugs is the Annonaceae (A. L. de Jussieu, 1789 nom. conserv., the Custard Apple Family). Annonaceae are widespread in the tropical world as a broad variety of trees, climbers, or shrubs which are quite easily spotted by their flowers that have a pair of whorls of leathery petals and groups of club-shaped fruits containing several seeds in a row (Figure 2.1). The inner bark itself is often fragrant and the plant is free of latex or sap; another feature is that the leaves are simple, alternate and exstipulate. In the Asia–Pacific, approximately 50 species from this family are medicinal, but to date there is not one on the market for clinical uses, a surprising fact since some evidence has already been presented that members of this family have potential for the treatment of cancer, bacterial infection, hypertension, and brain dysfunctions. Basically, there are three major types of active principles in this family: acetogenins, which often confer insecticidal properties, and isoquinolines and diterpenes of the labdane type (Figure 2.2).

2.2 FISSISTIGMA LANUGINOSUM (HK. F. ET TH.) MERR.

[From: Latin fiss = cleave and Greek stigma = mark made by pointed instrument, and Latin lanuginosum = wooly.]

2.2.1 Botany

Fissitigma lanuginosum (Hk. f. et Th.) Merr. (Melodorum lanuginosum Hk. et Th. and Uvaria tomentosa Wall.) is a climber which grows wild in the primary rain forests of Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Peninsular Malaysia. The stems are rusty, tomentose, woody, and with numerous lenticels. The leaves are simple, alternate, exstipulate, dark green and glossy above, oblong or oblong–obovate. The midrib above is rusty and pubescent, and the entire lower surface is densely rufous. The blade is 9cm − 21cm × 4cm − 8cm. The petiole is 1.5cm long. The flowers are arranged in terminal cymes. The sepals are 1–1.5cm long and rufous. The petals are coriaceous, oblong–lanceolate, the outer petals are up to 3.5cm long, while the inner ones are smaller. The fruits are ripe carpels which are subglobose, 2cm in diameter and dark brown (Figure 2.3).

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Author

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Annonaceae

- Chapter 3 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Myristicaceae

- Chapter 4 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Lauraceae

- Chapter 5 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Piperaceae

- Chapter 6 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Aristolochiaceae

- Chapter 7 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Nympheaceae

- Chapter 8 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Menispermaceae

- Chapter 9 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Polygonaceae

- Chapter 10 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Myrsinaceae

- Chapter 11 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Ebenaceae

- Chapter 12 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Bombacaceae

- Chapter 13 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Elaeocarpaceae

- Chapter 14 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Capparaceae

- Chapter 15 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Flacourtiaceae

- Chapter 16 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Passifloraceae

- Chapter 17 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Cucurbitaceae

- Chapter 18 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Connaraceae

- Chapter 19 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Anisophylleaceae

- Chapter 20 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Rosaceae

- Chapter 21 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Thymeleaceae

- Chapter 22 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Melastomataceae

- Chapter 23 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Rhizophoraceae

- Chapter 24 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Olacaceae

- Chapter 25 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Icacinaceae

- Chapter 26 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Euphorbiaceae

- Chapter 27 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Sapindaceae

- Chapter 28 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Anacardiaceae

- Chapter 29 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Simaroubaceae

- Chapter 30 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Meliaceae

- Chapter 31 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Rutaceae

- Chapter 32 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Loganiaceae

- Chapter 33 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Gentianaceae

- Chapter 34 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Apocynaceae

- Chapter 35 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Asclepiadaceae

- Chapter 36 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Solanaceae

- Chapter 37 Medicinal Plants Classified in the Family Verbenaceae

- Plant Index

- Chemical Compounds Index

- Subject Index