eBook - ePub

Metabolism and Molecular Physiology of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Metabolism and Molecular Physiology of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae

About this book

Since the publication of the best-selling first edition, much has been discovered about Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the single-celled fungus commonly known as baker's yeast or brewer's yeast that is the basis for much of our understanding of the molecular and cellular biology of eukaryotes. This wealth of new research data demands our attention and r

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Life cycle and morphogenesis

J. Richard Dickinson

1.1 Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to give a brief, general introduction to the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The various components of yeast’s life cycle are described in subsequent sections of this chapter. Details of the molecular events which govern and comprise (e.g.) the cell cycle, ageing, stress resistance, etc., are cross-referenced and can be found in later chapters.

1.2 Life cycle

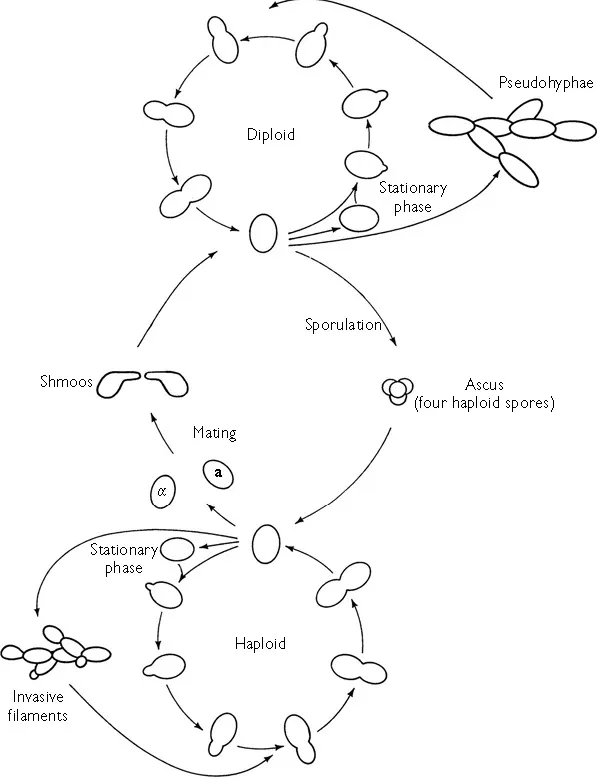

As shown in Figure 1.1, S. cerevisiae can exist both as a haploid and as a diploid. Given adequate nutrients both haploids and diploids can undergo repeated rounds of vegetative growth and mitosis. Yeast has a considerable number of alternative developmental options; the signals for all of these (except mating) are nutritional. Haploids exist in one of two mating types called a and α. Haploids of mating type a produce a pheromone (‘a factor’) and haploids of α mating type produce a pheromone (‘ α factor’). Each cell type has a cell surface receptor for pheromone produced by cells of the opposite mating type. a factor causes α haploids to arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle and α factor has the same effect on a cells. Consequently, when in each other’s presence, haploids of opposite mating type cease proliferation and commence the development of protuberances towards each other. The resultant shape is called a ‘shmoo’. Eventually, there is cell contact and subsequent fusion, culminating in the formation of a diploid.

When nutrients become depleted, both haploids and diploids arrest as stationary phase cells. These are morphologically and biochemically distinct from proliferating yeast cells. They are unbudded, round, phase-bright and contain much higher levels of the storage carbohydrates trehalose and glycogen than proliferating cells. Compared with proliferating cells, stationary phase cells also have increased resistance to a large number of stresses and adverse environmental conditions (Werner-Washburne et al., 1993).

Diploid cells starved of nitrogen and in the presence of a poor carbon source such as acetate will undergo meiosis and spore formation. Four haploid spores are formed which are contained within an ascus. The spores have even greater resistance to environmental extremes than stationary phase cells. If the spores are returned to rich nutrient conditions they will germinate and commence growth as haploids.

The life cycle of S. cerevisiae with its alternation between haplophase and diplophase is exploited in conventional strain construction. Haploids of opposite mating type, each having a certain desirable genotype are allowed to mate on a medium permissive to the growth of both and the diploid is duly formed. The mating mixture, containing the diploid is then replica-plated to a selective medium on which only the new diploid (but neither parental haploid) can grow. After a further day or two, the diploid is then replica-plated to a sporulation medium to induce sporulation. Because the formation of spores involves meiosis, some of the haploid progeny will have different combinations of genes and mutations from those present in the original parents. The ascus wall is digested away using glucanase and then the four individual spores from each ascus are transferred separately to fresh medium (using a micromanipulator) to grow as haploid clones. The precise combination of genes and mutations in each spore clone can be determined by analysing its phenotype and/or by a genetic screen (e.g. diagnostic polymerase chain reactions using specific primers).

Figure 1.1 The life cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (Redrawn from Dickinson (1999) with the permission of Taylor & Francis.)

Pseudohyphae and haploid filaments are easily recognized by their greater cell length and the fact that they form chains. They are both distinct developmental forms and are not merely ‘clumpy’ or sticky cells. It is generally believed that this filamentation allows foraging for nutrients away from the site where a colony initially resided. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has also been described as being able to form biofilm (defined as the ability to adhere to plastic) (Reynolds and Fink, 2001), an activity not normally associated with this organism. Key regulators of haploid invasive growth and diploid pseudohyphal formation are also required for biofilm formation (Kuchin et al., 2002).

1.3 Cell cycle

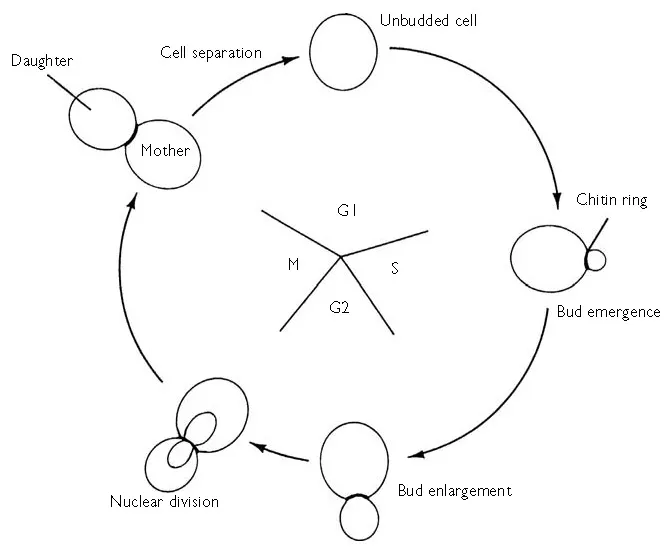

Yeast’s vegetative proliferation via budding (Figure 1.2) is one of the most well-known features in biology. The use of even an unsophisticated microscope will reveal bud initiation at the start of S-phase. The underlying molecular machinery started in G1 by the combination of the cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) Cdc28 with the G1 cyclins (Cln1, Cln2 and Cln3). (‘Cyclins’ were so-called because of their regular appearance and disappearance in each cell cycle.) The earliest activation event is from the association of Cln3 and Cdc28. This enables the transcriptional activators SBF (which comprises Swi4 and Swi6) and MBF (Swi4 and Mbp1) to start-off the transcription of CLN1 and CLN2. Consequently, the levels of Cln1 and Cln2 build up in late G1 thereby leading to the formation of Cln1–Cdc28 and Cln2–Cdc28 complexes which trigger the ‘Start’ commitment point to the cell cycle seen by bud emergence. The majority of genes induced at ‘Start’ have multiple binding sites for SBF and MBF in their promoters (Spellman et al., 1998). SBF and MBF bind to these genes (Iyer et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2001). There is a size control which operates over ‘Start’. Cells cannot pass ‘Start’ unless a minimum size (which varies according to the growth medium) has been reached. cAMP levels play a key role in controlling this step via cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) which simultaneously inhibits the transcription of CLN1 and CLN2 (Baroni et al., 1994; Toikwa et al., 1994) and promotes growth (probably by a direct stimulation of protein synthesis (Ashe et al., 2000) ). Since Cln3 levels are mainly regulated at the level of translation, the increased protein synthesis leads to an increase in the amount of Cln3 in the cell and the induction of CLN1 and CLN2 as already described.

Figure 1.2 Simplified representation of the cell cycle of S. cerevisiae. (Redrawn from Dickinson (1999) with the permission of Taylor & Francis.)

A number of other events are also triggered at ‘Start’ including the initiation of DNA synthesis, polarized growth and the duplication of spindle pole bodies. The Cln1–Cdc28 and Cln2–Cdc28 complexes lead to the expression of other cyclins (Clb1–6) which control the activity of the Cdc28 protein kinase at subsequent stages of the cell cycle. Clb5–Cdc28 and Clb6–Cdc28 promote DNA replication whilst the association of Clb1–4 with Cdc28 causes the cell to be propelled towards mitosis. Clb–Cdc28 complexes also serve to inhibit re-budding later in the cell cycle (Lew and Reed, 1993, 1995; Amon et al., 1994; Shimada et al., 2000). The functioning of Cdc28 in the cell cycle (as far as it is understood) is described in full in Chapter 8 and Figure 8.2.

The attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle triggers the anaphase–metaphase transition in which the anaphase p_romoting complex (APC) causes the ubiquitination of proteins which are proteolytically cleaved so as to allow anaphase and exit from mitosis. Cdc20 and Cdh1 activate APC towards its targets. Three subunits of APC (Cdc16, Cdc23 and Cdc27) are phosphorylated by Cdc28, which results in the activation of Cdc20. Cdc28 also phosphorylates Cdh1, which inactivates it and thereby renders it unable to bind APC. APCCdc20 causes the degradation of Pds1 that starts a chain of events culminating in the separation of sister chromatids (see Chapter 8, pp. 292–294). For the next stage (mitotic exit) Clbs are destroyed so that Cdc28 protein kinase activity is rendered low once more. APCCdh1 destroys the Clbs. Cdh1 is activated by dephosphorylation, which is principally accomplished by Cdc14. Until recently, it was thought that degradation of Clb5 was necessary for the dephosphorylation and activation of Cdh1 and (the Cdk inhibitor) Sic1 (Morgan, 1999; Zachariae and Nasmyth, 1999). However, Wäsch and Cross (2002) have shown that spindle disassembly and cell division occurred without significant APCCdc20-mediated Clb5 degradation and in the absence of both Cdh1 and Sic1. These authors report that destruction box-dependent degradation of Clb2 was essential for mitotic exit and state that ‘APCCdc20 may be required for an essential early phase of Clb2 degradation, and this phase may be sufficient for most aspects of mitotic exit. Cdh1 and Sic1 may be required for further inactivation of Clb2–Cdk1, regulating cell size and the length of G1’ (Wäsch and Cross, 2002).

Cyclic AMP is also involved in the metaphase–anaphase transition and in the exit from mitosis by inhibiting the onset of anaphase and exit from mitosis in response to growth rate (Spevak et al., 1993; Anghileri et al., 1999). Yeast mutants defective in their APC are inviable on media with high concentrations of glucose but can be rescued by ras2Δ, or cdc25 mutations, or elevated levels of the high Km cAMP phosphodiesterase Pde2, all of which reduce cAMP levels in the cell (Irniger et al., 2000). Hence, cAMP levels influence the timing of the G1–S transition, and exit from mitosis, and consequently the cell size at budding and at division.

The yeast cell cycle comprises an array of ‘checkpoint controls’ whereby cell cycle progression is prevented if certain necessary processes have not taken place for example, mitosis is delayed if DNA replication has not been completed or if damage has occurred to DNA, the actin cytoskeleton or the mitotic spindle. Abnormality in the actin cytoskeleton prevents bud formation with a consequent delay to mitosis through negative regulation of Clb–Cdc28 by Swe1 (McMillan et al., 1999). In response to bud formation, Swe1 is negatively regulated by Hsl1 (Ma et al., 1996; McMillan et al., 1999; Lew, 2000; Longtine et al., 2000). Swe1 is targeted to the bud neck after formation. The interacting proteins Hsl1 and Hsl7 are required for neck localization (Shulewitz et al., 1999; Longtine et al., 2000). Thus, morphogenesis is coupled to proliferation.

The morphogenic aspects of the yeast cell cycle are considerable. These include bud site selection, polarity, pattern and rate of growth of the daughter cell and organellar distribution. The budding pattern of haploids and diploids is different. In rich media haploids bud in an axial pattern whereas normal MATa/MAT α diploids show polar budding (Figure 1.3). (Homozygous MATa/MATa and MAT α/MAT α diploids also bud axially.) The complete story is more complicated than this however, because environmental conditions also affect the budding patterns of both haploids and diploids. Since yeast cells are rarely in constant conditions (in batch cultivation and on Petri dishes the composition of the medium changes as a consequence of yeast metabolism and proliferation), these differences have implications not only for normal vegetative ‘yeast form’ proliferation but also for the various developmental alternatives such as the formation of invasive filaments by haploids and pseudohy-phae by diploids (see Section 1.5).

Two fundamentally different patterns of growth occur during different portions of the yeast cell cycle. The emerg...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Life Cycle and Morphogenesis

- Chapter 2: Mother Cell-Specific Ageing

- Chapter 3: Carbon Metabolism

- Chapter 4: Nitrogen Metabolism

- Chapter 5: Molecular Organization and Biogenesis of the Cell Wall

- Chapter 6: Lipids and Membranes

- Chapter 7: Protein Trafficking

- Chapter 8: Protein Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation

- Chapter 9: Stress Responses

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Metabolism and Molecular Physiology of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae by J. Richard Dickinson, Michael Schweizer, J. Richard Dickinson,Michael Schweizer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.