eBook - ePub

Organelles, Genomes and Eukaryote Phylogeny

An Evolutionary Synthesis in the Age of Genomics

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organelles, Genomes and Eukaryote Phylogeny

An Evolutionary Synthesis in the Age of Genomics

About this book

The recent revolution in molecular biology has spread through every field of biology including systematics and evolution. Researchers can now analyze the genomes of different species relatively quickly, and this is generating a great deal of data and theories about relationships between taxa as well as how they originated and diversified.

Org

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organelles, Genomes and Eukaryote Phylogeny by Robert P Hirt,David S. Horner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

An Overview of Eukaryote Origins and Evolution: The Beauty of the Cell and the Fabulous Gene Phylogenies

David S.Horner and Robert P.Hirt*

Abstract

Eukaryotic organismal diversity is underpinned by an extraordinary organizational diversity at the cellular and molecular levels. Comparative cell and molecular biological studies on a broad range of eukaryotes are yielding a large number of surprising results. This chapter presents an overview of some of these results and illustrates how some of this diversity is now appreciated within an evolutionary framework. It discusses some of the most interesting new hypotheses on eukaryote evolution and the methodological advances needed to rigorously test them, and in so doing highlights the significance of the other chapters making up this book. It focuses on the impact of studies of microbial eukaryotes and organelles of endosymbiotic origin on our current understanding of both the origin and the evolution of eukaryotes. We speculate that comparative biology (not restricted to comparative genomics) of a broad diversity of microbial eukaryotes will be critical to the development of biological science in the 21st century.

1.1 Introduction

The past 10 years have seen dramatic advances in the understanding of eukaryote diversity, evolution and cellular and genomic organization. Much of this progress has come through the unprecedented rate of production of molecular sequence data from an increasingly wide range of organisms, presenting biologists with new opportunities and challenges in the investigation of eukaryote evolution and origin. This, in turn, has clearly demonstrated the importance and value of comparative and evolutionary biology in investigating and under-standing genome data. Recent years have also seen an increase in the cross-talk among disparate areas of biological expertise, with multidisciplinary approaches to investigating the bewildering and beautiful complexity of cellular life becoming the norm. The objective of this book is to provide a synthesis of current views on (1) eukaryote diversity and phylogeny, (2) molecular and organellar diversity among eukaryotes, (3) the role of endosymbiosis in the evolution of eukaryotes, (4) the importance of evolutionary and molecular systematic perspectives in analysis and exploitation of genome sequence data and (5) the role and importance of epigenetics, including membrane heredity, in the evolution of the cell. The latter is an often-neglected topic of great interest and importance for the biology of the 21st century, since genomes do not contain all the information required to bring about cells and their phenotypes (e.g., Kirschner et al., 2000; Jablonka and Lamb, 1995).

By way of introducing the various contributions that have been selected for this book, we hope to provide a succinct history of molecular phylogenetic investigations into eukaryote origins and evolution and show how a sound molecular systematic framework for eukaryotes and prokaryotes is key for the comparative analysis of eukaryote genomes. By doing so, we hope to emphasize the plastic and chimeric nature of eukaryote genomes and membranes and the complex interplay between these two entities during eukaryote evolution. Finally, we hope to illustrate how little is known about several major eukaryotes lineages, for some of which our knowledge is limited to a few gene sequences.

1.2 The Ribosomal RNA Paradigm and the Archezoa Hypothesis

More than a quarter of a century ago, Carl Woese and his co-workers published a seminal series of papers that indicated, using a universally distributed molecular phylogenetic marker (the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, SSUrDNA) and molecular cell biological features, that extant life on earth is divided into three primary lines of descent (Woese, 1987) rather than two as in the traditional prokaryote-eukaryote divide (Doolittle, 1996), with the eubacteria (or Bacteria), archaebacteria (Archaebacteria or Archaea) and eukaryotes (spelled either Eucaria or Eukarya) forming the so-called three Domains of life (Woese et al., 1990). By the mid-1980s, incorporation of SSUrDNA sequences from mitochondria and chloroplasts into the tree of life substantiated the long-suspected (Mereschkowsky, 1905; Margulis, 1970, 1993; Martin et al., 2001) endosymbiotic origin of these organelles from alpha-proteobacteria and cyanobacteria, respectively (Woese, 1987). The number of organisms and taxonomic groups represented in the SSUrDNA tree has increased at an impressive rate; there are currently in excess of 5000 sequences for eukaryotes alone (Cole et al., 2003). The SSUrDNA tree also represents an important reference point for investigating the phylogeny of uncultured eukaryotes. Sequences isolated directly from environmental samples (rather than from specific organisms) are beginning to accumulate and these could potentially have an important impact on the perception of eukaryote diversity and evolution by identifying significant new lineages (Moreira and López-García, 2002; Stoeck and Epstein, 2003) as has been the case for environmentally derived SSUrDNA sequences from Bacteria and Archaea (DeLong and Pace, 2001). These new sequences can then be linked with specific organisms to allow further investigations of their biology, possibly leading to surprising discoveries about their cellular and genomic features. Such findings might even increase our understanding of eukaryote origins.

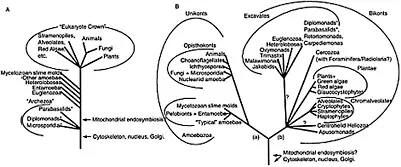

SSUrDNA trees have also provided a stimulating framework for the comprehension of early eukaryote evolution by recovering a group of sequences from a disparate collection of amitochondriate microbial eukaryotes at the base of the tree, rather distant (in terms of branch length) from the best-known and most intensively investigated animals, fungi and plants (Woese, 1987; Sogin, 1991; Hedges, 2002). The latter were defined as the crown taxa and the former as early branching eukaryotes (e.g., Sogin et al., 1996; Figure 1.1A).

The perceived simplicity of early branching eukaryotes (organisms such as diplomonads and microsporidia apparently lacked mitochondria, peroxisomes, Golgi dictyosomes and, in the case of microsporidia, flagella), combined with their early branching position in the eukaryotic SSUrDNA tree, was seen as consistent with the existing notion that these lineages were primitively amitochondriate and that simpler cells precede more complex ones (e.g., Patterson, 1994; Sogin et al., 1996; Cavalier-Smith, 1993). This engaging parallel between cellular simplicity and basal phylogenetic position was formalized as the Archezoa hypothesis (e.g., Cavalier-Smith, 1993; also see Chapter 2).

Several laboratories were tempted to test the clear premises and implications of the Archezoa hypothesis and initiated research programs on the phylogenetics, comparative genomics and cell biology of several Archezoa (e.g., Patterson and Sogin, 1993; Embley and Hirt, 1998; Roger, 1999; Philippe et al., 2000b; also see Chapters 2, 10 and 13). During the 1990s, a series of experiments demonstrated that the apparently amitochondriate entamoebids (Clark and Roger, 1995), parabasalids (Bui et al., 1996; Germot et al., 1996; Horner et al., 1996; Roger et al., 1996), diplomonads (Roger et al., 1998; Horner and Embley, 2001) and microsporidia (Hirt et al., 1997; Germot et al., 1997; Peyretaillade et al., 1998) harbored genes encoding heat shock proteins that were apparently of mitochondrial origin. Furthermore, microsporidia had been shown not to be early branching eukaryotes but to be related to, or even to branch within, Fungi through phylogenies derived from various protein-coding genes and large subunit rDNA (e.g., Edlind et al., 1996; Hirt et al., 1999; van de Peer et al., 2000a; Keeling, 2003). Cell biological studies also revealed that the hydrogenosomes of parabasalids (e.g., Dyall and Johnson, 2000) and hitherto-unrecognized double-membrane-bound organelles in entamoebids (Tovar et al., 1999; Mai et al., 1999) and microsporidians (Williams et al., 2002) likely descended from the same endosymbiotic event that gave rise to mitochondria. More recent evidence suggests that diplomonads also contain relict mitochondria (Tovar et al., 2003). Together, these data clearly falsify the Archezoa hypothesis, push back the probable timing of the mitochondrial endosymbiosis to before the divergence of any known extant eukaryotic lineage and make it difficult to establish whether the nucleus or mitochondria arose first.

1.3 From SSUrDNA Trees to Protein-Coding Gene Trees

The testing of the Archezoa hypothesis illustrated both the significance (in providing key primary phylogenetic hypotheses) and the weaknesses of the stimulating and intuitively appealing eukaryotic SSUrDNA tree topologies. The implication that SSUrDNA trees might

FIGURE 1.1 The early SSUrDNA-based eukaryotic phylogeny contrasted with the new-generation trees recovered from new phylogenetic analyses and other considerations. (Adapted from Figure 1 in Simpson and Roger (2002) R691–R693 and Figure 1 in Stechmann and Cavalier- Smith (2002a) 89–91. (A) Schematic SSUrDNA tree from the early 1990s [e.g., Sogin (1991) 457–463; Sogin et al. (1996) 167–184]. Such trees were often obtained by using distance methods and little consideration was given to the fit of the substitution model to properties of the data under consideration (e.g., base composition and rate heterogeneity between sites— see text and Chapter 6). Distant prokaryotic sequences were typically used as outgroups. These analyses are now thought to have been affected greatly by long-branch artifacts (see Chapter 6). The three major Archezoa clades at the base of the tree are highlighted with the symbol*. (B) More recent views on eukaryote phylogeny based on various analyses of protein alignments [e.g., Baldauf et al. (2000) 972–977; Lang et al. (2002) 1773–1778; Bapteste et al. (2002) 1414–1419], reanalyses of SSUrDNA datasets [e.g., Van de Peer et al. (2000b) 565–576; Cavalier-Smith (2002a) 297–354) and protein gene fusion events [Stechmann and Cavalier-Smith (2002) 89–91; (2003) 665–R664]. Two sets of gene fusion events suggest that the root of the eukaryotic tree might be positioned between two major clades, defined as the unikonts (uniciliates) and bikonts (bicilia) [Cavalier-Smith 2002a; Stechmann and Cavalier-Smith (2003) R665–R664]. A fusion of the genes encoding carbamoyl phosphate synthase, dihydroorotase (DHO) and aspartate carbamoyltransferase (ACT) supports the monophyly of the unikonts, branch labeled (a). A fusion of the genes encoding dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and thymidylate synthase (TS), branch labeled (b), suggests monophyly of the bikonts [Stechmann and Cavalier-Smith (2003) R665–R664]. The new positions of three former Archezoa are highlighted by the symbol*.

not be infallible prompted a serious reappraisal of the choice of phylogenetic markers and a more critical use of phylogenetic reconstruction methodologies (e.g., Embley and Hirt, 1998; Philippe and Adoutte, 1998). Protein-coding genes were increasingly used to investigate the global phylogeny of eukaryotes with both nuclear (e.g., Baldauf et al., 2000; Bapteste et al., 2002) and mitochondrial coding genes (Lang et al., 2002) contributing to new hypotheses for the phylogeny of eukaryotes (see later and Figure 1.1B).

1.3.1 Availability of Molecular Phylogenetic Markers and the Advent of Genomics

Although the primary gene cloning efforts were on a gene-by-gene basis, genome sequencing projects along with partial genome surveys [genome sequence surveys (GSSs) and expressed sequence tags (ESTs)] increasingly represent the principal sources of molecular sequence data. The first eukaryotic nuclear genomes to be completed were those of the classical model organisms Saccharomyces cerevisiae (1997), Caenorhabditis elegans (1998), Drosophila melanogaster (2000), Arabidopsis thaliana (2000) and Homo sapiens (2001), for which a large amount of functional and physiological data had already accumulated. More recently, molecular phylogenetic considerations and the fact that most of the early branching taxa are parasites have stimulated the selection of several of these organisms for genome sequencing. The phylogenetic questions about these organisms make them interesting and important genomic models (Sogin, 1993; Hedges, 2002). These include the microsporidia, represented by the genome of Encephalitozoon cuniculi (Katinka et al., 2001; Chapter 10), the diplomonad Giardia lamblia (McArthur et al., 2000—The Marine Biology Laboratory: http://jbpc.mbl.edu/Giardia- HTML/index2.html), the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica and relatives (TIGR: http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/eha1/ and the Sanger Institute: http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/E_histolytica/) and more recently the parabasalid Trichomonas vaginalis (TIGR: http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/tvg/). In addition to these genome projects, other microbial eukaryote genomes (including additional fungi and algae) have been, or are currently being, fully sequenced or investigated through EST and GSS projects (e.g., Bapteste et al., 2002). A recently launched Canadian EST program covering several major eukaryotic lineages (see list at http://megasun.bch.umontreal.ca/pepdb/pep.html) is particularly notable in this respect. For a listing of such projects, readers are referred to the informative genome online database (GOLD) at http://wit.integratedgenomics.com/GOLD/ (Bernal et al., 2001) and to the GOBASE database of organellar genome projects (O’Brien et al., 2003). The databases housing these and future genome sequences represent a rich source of data for investigating eukaryote phylogeny and cell and genome evolution.

One important conclusi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contributors

- Chapter 1: An Overview of Eukaryote Origins and Evolution: The Beauty of the Cell and the Fabulous Gene Phylogenies

- Section I: Eukaryote Diversity and Phylogeny

- Chapter 2: Excavata and the Origin of Amitochondriate Eukaryotes

- Chapter 3: The Evolutionary History of Plastids: A Molecular Phylogenetic Perspective

- Chapter 4: Chromalveolate Diversity and Cell Megaevolution: Interplay of Membranes, Genomes and Cytoskeleton

- Chapter 5: Origin and Evolution of Animals, Fungi and Their Unicellular Allies (Opisthokonta)

- Section II: Phylogenetics and Comparative Genomics

- Chapter 6: Pitfalls In Tree Reconstruction and the Phylogeny of Eukaryotes*

- Chapter 7: The Importance of Evolutionary Biology to the Analysis of Genome Data

- Chapter 8: Eukaryotic Phylogeny In the Age of Genomics: Evolutionary Implications of Functional Differences

- Chapter 9: Genome Phylogenies

- Chapter 10: Genomics of Microbial Parasites: The Microsporidial Paradigm

- Chapter 11: Evolutionary Contribution of Plastid Genes to Plant Nuclear Genomes and Its Effects on Composition of the Proteomes of All Cellular Compartments

- Section III: Evolutionary Cell Biology and Epigenetics

- Chapter 12: Protein Translocation Machinery In Chloroplasts and Mitochondria: Structure, Function and Evolution

- Chapter 13: Mitosomes, Hydrogenosomes and Mitochondria: Variations on a Theme?

- Chapter 14: Eukaryotic Cell Evolution from a Comparative Genomic Perspective: The Endomembrane System

- Chapter 15: The Membranome and Membrane Heredity In Development and Evolution

- Chapte: 16 Epigenetic Inheritance and Evolutionary Adaptation

- Systematics Association Publications