- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creating Neighbourhoods and Places in the Built Environment

About this book

This design primer examines the forces at work in the built environment and their impact on the form of buildings and their environments. The actions of a range of individuals and agencies and the interaction between them is examined, exploring the competing interests which exist, their interaction with physical and environmental forces and the uncertain results of both individual and corporate intervention.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Creating Neighbourhoods and Places in the Built Environment by David Chapman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architektur & Stadtplanung & Landschaftsgestaltung. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE DEVELOPMENT OF SETTLEMENTS

CHAPTER ONE

NATURE AND SETTLEMENT

L. JOHN WRIGHT

THEME

Each local region, neighbourhood and place has its own unique and dynamic natural environment. Human settlement evolves, partly in response to the infinite variations in environmental conditions, in order to maximize utility and comfort for inhabitants. From earliest times the human race has endeavoured not only to adapt to natural elements but to modify and control them. In the modern world of accelerating population growth and urbanization, the impacts of settlement on natural systems are ever increasing.

Several fundamental questions arise which are important considerations for any student or professional working in the built environment field:

- How far do natural factors influence the siting, form and buildings of rural settlements?

- How much do natural forces influence the location and development of towns and cities?

- What impacts do settlements have on their natural environment?

- Can such impacts be controlled in order to ensure sustainability of settlements within their natural surroundings?

This chapter discusses these issues and looks for possible answers to these key questions.

OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- understand how far geology, landforms and soils influence rural settlement forms;

- appreciate how siting and development of towns and cities are influenced by geology and landforms;

- recognize ways in which urban development is affected by natural barriers;

- appreciate where settlements have not adapted to environments adequately;

- identify ways in which natural landscapes have been modified or controlled for development purposes;

- understand how weather and climate can affect building forms and settlement;

- assess the overall interactions of settlements with natural environment and be able to consider the issue of their mutual sustainability.

INTRODUCTION

Before proceeding further it is worth clarifying what is meant by ‘nature’ and ‘settlement’ in the context of this chapter. Nature, or the natural environment, comprises different but interrelated systems. These systems are often studied together as physical geography or within a multidisciplinary environmental studies or earth science package. They can be simplified into four major systems:

- the lithosphere, or land system (geology, landforms and soils);

- the atmosphere, or air system (weather, climate and air quality);

- the hydrosphere, or water system (seas, surface fresh water, ground water and ice);

- the biosphere, or life system (plant and animal organisms).

Settlement can be taken simply to refer to any human habitations or dwellings, but settlements are organized into different patterns or distributions. Rural settlement patterns may be dispersed (consisting of single isolated dwellings or farms), clustered (with loosely spaced groups of dwellings) or nucleated (with closely spaced groups of dwellings). Smaller nucleated settlements with between three and 19 dwellings may be termed hamlets. Those with 20 or more dwellings can be referred to as villages[1]. Urban settlements (towns and cities) are distinguishable from villages not only by virtue of their size, normally consisting of at least several hundred dwellings, but also because of their wider range of functions and services.

WORKPIECE 1.1

FORMS OF RURAL SETTLEMENT

Study any reasonably large-scale map available for a rural area in your own region or country (e.g. 1:50 000, 1:25 000 or 1:10 000), Using the descriptive terms for rural settlement types defined in the introductory section:

- Identify any differences in the overall density of rural settlement in the area covered by the map. Where are the most and least villages, hamlets, clusters and isolated dwellings?

- Distinguish any variations in settlement form in the area concerned. Are there more or larger nucle-ated settlements in some districts than others? Are some parts of the map more characterized by dispersed settlement than others?

- Draw a sketch map of the area and divide it according to types of rural settlement that you have recognized.

Having defined what we mean by ‘nature’ and ‘settlement’ it is possible to begin to consider how they interrelate. Settlements and settlement patterns evolve through complex interactions between the physical (natural), socio-economic and cultural groups of forces. So just how influential are the natural forces regarding the evolution of settlements? To approach answers to this question it is proposed first to examine rural settlement patterns and then analyse aspects of urban forms.

NATURE AND RURAL SETTLEMENT

Natural forces operate at different geographical scales. At a regional scale do they help to create contrasts in rural settlement forms, say over some hundreds of kilometres? How far do they exert a local influence regarding general situations of settlements to within a few kilometres? How do they influence the precise siting of settlements perhaps to within a few scores of metres?

Illustrations of rural settlement can be drawn from England and Wales in the UK. Even in such a densely populated, industrialized and urbanized country there are contrasting rural forms of ancient derivation. Historians know that these patterns were largely established by the mediaeval period (AD 1100–1400) and so date from times when the rural economy was based on subsistence agriculture. Do these patterns in any way show varied adaptations by farming communities to natural forces, especially those of relief, geology, soils and climate?

REGIONAL SCALE

In England and Wales four broad regional rural settlement zones are recognizable [2](Figure 1.1):

- a middle zone of England dominated by villages with relatively few hamlets or scattered farms;

- a western zone of England characterized by hamlets, small clusters and dispersed homesteads with some villages;

- Wales, parts of the English south-west peninsula and extreme north of England with predominant dispersed settlement with some clusters and hamlets;

- some southern and south-eastern regions of England with a mix of settlement forms including dispersed dwellings, clusters, hamlets and villages.

Figure 1.1 Regional rural settlement types in England and Wales.

Analysis of physical geography does indicate that natural forces were very significant formative influences. The middle zone corresponds with some of the most naturally favoured farming regions. It is generally underlain by younger Mesozoic rocks, good soils are usual, lowland (below 200 m) predominates and rainfall is not excessive (generally 550–700 mm per annum). Greater potential for food crops could support a larger population and nucleated villages.

The western zone has more of the older Palaeozoic geology, less consistently good soils, more uplands (above 200 m) and more rainfall (usually above 700 mm even on lowlands). Natural conditions were less conducive to supporting a dense population and any nucleations tended to be smaller hamlets.

In Wales, the south-west and the north, the older Palaeozoic rocks produce chiefly poorer acid soils and hill country with higher rainfall (often 1000 mm on low ground and 2000 mm in hill regions). In Britain this combination of natural factors makes ripening of basic cereal crops difficult and more reliance has to be placed on pastoral farming (sheep and cattle). This farming economy supported a smaller dependent population in scattered rural settlements. In some parts of south and south-east England a mix of settlement forms is perhaps less easily explained in natural terms.

Natural forces are just one set of several very important forces which influence rural settlement. Economic, social and cultural forces are significant, especially concerning how land was farmed. This is evident in England and Wales. The middle zone of nucleated settlement corresponds to rich cropping lands but also to regions where the English (or Anglo-Saxon) settlement and socio-economic organization dominated. Anglo-Saxon settlers came from north Germany in the fifth and sixth centuries. They later developed an agricultural organization which culminated in the manorial system after the Norman Conquest. This system was based on three open arable fields cultivated communally and so centred on the typical nucleated village.

Hamlets and dispersed patterns in the western zone demonstrate the English response to less favourable farming country. Small nucleated settlements were supported by smaller open fields in pairs, rather than threes, and scattered farms often represent mediaeval forest clearings or continued occupation of pre-English settlement sites.

By contrast Wales, the south-west and the northern hill areas retained cultural and economic occupancy by older Celtic-speaking populations. Brythonic Celtic, or Welsh as it has become, survives still in north and west Wales. These Celtic peoples had small scattered plots of arable land with isolated farmhouses, or small clusters of houses, within a tribal area devoted largely to grazing lands. Dispersed patterns resulted and even churches were located in isolation.

Some ancient villages occur in southern and south-eastern regions of England. However, varied physical landscapes and early opportunities for commercial (as opposed to communal subsistence) farming near London were possible factors leading to divergent settlement patterns.

What conclusions emerge from this analysis of regional rural patterns in England and Wales? Here are three to consider:

- Ancient variations in rural settlement pattern persist.

- Different patterns evolved in part as adaptations to variable natural environments and forces.

- Economic and cultural forces were influential, especially those emanating from the differences in organization of subsistence farming.

Brian Roberts, in his book Rural Settlement in Britain, summarizes the important role of natural forces by advising his reader: ‘It is well to appreciate the extent to which physical factors can operate indirectly on settlement through the intermediary of economic activity’ [3].

LOCAL SCALE

Interactions between natural forces and rural settlement evolution can be appreciated even more by closer analysis of a local area. This is especially so where there are obvious contrasts in physical environment linked with what has been historically a cultural transitional zone. Such areas exist along the borders between England and Wales. One has been selected for detailed study in Example 1.1.

EXAMPLE 1.1

LOCAL NATURAL ENVIRONMENT: EASTERN RADNORSHIRE, POWYS, MID WALES

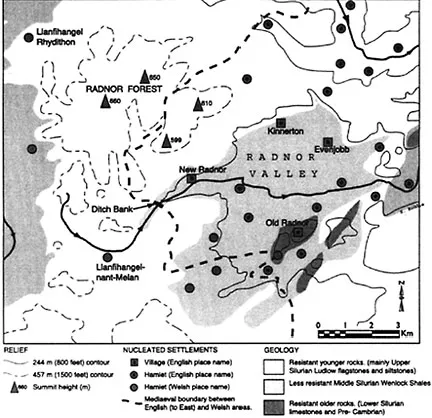

This example is in the middle Welsh Borderland (Figure 1.1 for location). Contrasts in natural environment can be distinguished (Figure 1.2). The wide Radnor Valley is below 250 m (800 feet) and relatively flat. It is largely enclosed by hills, the highest being the Radnor Forest range to the north-west rising to 660 m (2166 feet).

Geological underpinning for these marked landform differences is easy to interpret (Figure 1.2), The valley area coincides almost exactly with the extent of the Silurian Wenlock Shales outcrop, the least resistant rocks in the local district. Surrounding hills are formed from more resistant geology, mainly younger Silurian Ludlow Series (mudstones, siltstones and flagstones) but with outcrops of limestone and hard Precambrian rocks to the south-east.

The Radnor Valley floor is covered by silts and gravels deposited by ice and glacial meltwaters at the close of the Ice Age (c. 18 000 to 14 000 years ago). These give fertile well-drained soils and good water supplies to contrast with mainly thin, very acid soils in the hills.

There are appreciable variations in annual rainfall totals, In the Radnor Valley annual averages are about 1100 mm (44 inches) in the west and as low as 900 mm (36 inches) in the east. Over the Radnor Forest hills, rainfall averages as much as 1400 mm (55 inches) accompanied by greater cloudiness and lower temperatures with increased altitude.

Figure 1.2 Local natural environment and rural settlement: eastern Radnorshire, Powys, Mid-Wales.

The natural environment d...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT SERIES OF TEXTBOOKS (BEST)

- LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART ONE THE DEVELOPMENT OF SETTLEMENTS

- PART TWO THE QUALITIES OF PLACES

- PART THREE CREATING PEOPLEFRIENDLY PLACES