- 626 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Science and Skiing

About this book

The first International Congress on Science and Skiing was held in Austria in January 1996.

The main aim of the conference was to bring together original key research in this area and provid an essential update for those in the field. The lnk between theory and practice was also addressed, making the research more applicable for both researchers and coaches.

This book is divided into five parts, each containing a group of papers that are related by theme or disciplineary approach. They are as follows: Biomechanics of Skiing; Fitness testing and Training in Skiing; Movement Control and Psychology in Skiing; Physiology of Skiing and Sociology of Skiing.

The conclusions drawn from the conference represent an invaluable practical reference for sports scientists, coached, skiers and all those involved in this area.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Taylor & FrancisYear

2003Print ISBN

9780419208501eBook ISBN

9781135818104Part One

Biomechanics of Skiing

1

SKI-JUMPING TAKE-OFF PERFORMANCE: DETERMINING FACTORS AND METHODOLOGICAL ADVANCES

Department of Biology of Physical Activity, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: ski-jumping, force measurements, neuromuscular function, kinematics, electromyography.

1 Introduction

Ski-jumping is a very complex skill involving several phases—in-run, takeoff, flight and preparation for landing-, each of which has importance to the length of the jump. In general the skill includes both ballistic and aerodynamic factors. The ballistic factors refer to release velocity and release position from the take-off table, whereas the gliding properties of the jumper/ skis system (velocity, suit design, surface area, posture of the jumper/skis system, turbulance and resisting and lifting forces) belong to the aerodynamic factors during the flight. It is important to realize that both ballistic and aerodynamic factors place special demands on the jumper so that he could optimally maximize the vertical lift and minimize the drag forces.

Take-off is probably the most crucial phase for the entire ski-jumping performance. The purpose of the take-off is to increase the vertical lift and simultaneously maintain or even increase the horizontal release velocities. It is therefore important to emphasize that it is the jumper and his ability to perform a skillful take-off and the subsequent flight phase, which finally determines the length of the jump. For this reason much is required from the jumper’s neuromuscular system, especially because of the unusually short time available for execution of the take-off performance.

The present article makes an attempt to review factors which are involved in take-off performance. Special efforts will be made to characterize the take-off action and link this to the relevant neuromuscular functions of the jumper. Techiques of measurement of the actual take-off forces have improved considerably during the last two decades. These aspects are also described both methodologically and with respect to the neuromuscular requirements and especially how they are related to the length of the jump. Integration of muscle activation patterns with take-off technique is also relevant for the understanding of the ski-jumping performance. These aspects will be highlighted also with prospects for future measurement techniques.

2 Important take-off parameters and their characteristics

Ski-jumping take-off is performed from a crouch position (Fig. 7) during a very short time, ranging from 0.25 to 0.30s [1] [2]. This time period covers on the average 7.1 m from the take-off table. Thus the first take-off movements are initiated during the transition phase from the end of the inrun curve to the flat table. This phase is very crucial for the timing and coordination of the movements due to sudden disappearance of the centrifugal force at the end of the in-run curve. Kinematically the rapid take-off movement can then be characterized by changes in two major angles: hip and knee. The hip angle displacement is, on the average, from 40° to 140° [2] [3] emphasizing that the hip extension continues in the air after the take-off edge has been passed (Fig. 1). Similarly the knee-joint extension (from 70° to 140°) is not complete during the take-off table. However, the knee-extension velocity reaches a very high value of over 12 rad×s-1 [4], which is usually reached a few ms before passing the take-off edge. In the optimal take-off, the hip extension velocity is also relatively high ( ≈10 rad ×s-1)[4], and it is caused mainly by the thigh movement, but with a smaller upper body extension [3]. Thus the upper body is maintained in a lower position to reduce the drag forces [5] (see also Fig. 16). This adds to the lift forces with resulting reduction in the load for the extension movement. According to the force-velocity relationships of the muscle, the light load can be moved with higher movement velocity [6] [7]. The knee-extension velocity is reportedly the highest correlating factor of all take-off parameters to the distance jumped [3]. The powerful knee-extension movement therefore results in a suprisingly high vertical velocity (Vv, normal to the take-off table) of the center of mass of the jumper/ski system. Velocities, such as between 2.3 and 3.2 m×s-1 are not unusual [1] [2] [5].

Fig. 1. Progession of the knee, hip and shank ski angles before and after the take-off instant. The take-off movement begins, on the average, 0.28 s before the release instant (dashed vertical line) [2].

In addition to high vertical and horizontal velocities, the purpose of the take-off movement is also to produce angular momentum. The somersault angle, defined as an angle between a line connecting the knee and shoulder joint center to the global longitudinal axis has been used to describe the production of forward momentum in ski-jumping take-off [3]. A greater angular velocity enables the jumper to prepare for and subsequently assume the flight position as rapidly as possible from the take-off. There may therefore be a slight contradiction in that the impulse at take-off is necessary to achieve height and to generate angular momentum.

To obtain maximal height the jumper’s center of mass (CM) must be located along the line of action of the vertical ground-reaction force, whereas the production of angular momentum requires the CM to be located anterior to this line. Evidence has been presented that the more succesful jumps are characterized by higher knee extension velocities and simultaneously by a more rapidly decreasing somersault angle towards the take-off edge [3].

3 Limiting neuromuscular factors in ski-jumping take-off

The preceeding description of the take-off parameters is naturally selective and somewhat simplified. Its purpose was, however, to highlight those factors which can then be related to and interpreted by the function to the jumper’s neuromuscular system. Short take-off time, high knee angular velocity and low upper body position are special requirements and very specific to ski-jumping. Clarifications to the problems from the point of view of neuromuscular limiting factors can be derived from the well-known curves describing the force-time, force-velocity, as well as force-length relationships of the isolated human skeletal muscles and muscle groups. The possibility of utilization of muscle elasticity for the maximization of take-off potential must also be examined.

3.1 Force-time curve

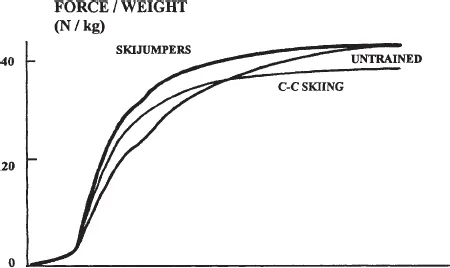

In isometric conditions, when the muscle is maximally activated the force production to the highest level requires in human leg extension 600–1200 ms (Fig. 2). When this is compared to the time available for the take-off movement (28 ms), one can understand that the time to produce force is indeed a limiting factor in ski-jumping.

Fig. 2. Force-time characteristics of the bilateral isometric leg extension among ski-jumpers, untrained controls (policemen) and crosscountry skiers [8].

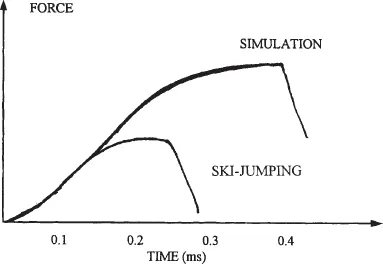

Fig. 3. Schematic presentation of the vertical force-time relationships in actual ski-jumping take off and in a simulated ski-jumping take-off in the laboratory. Please note that the time is a limiting factor in actual ski-jumping take-off.

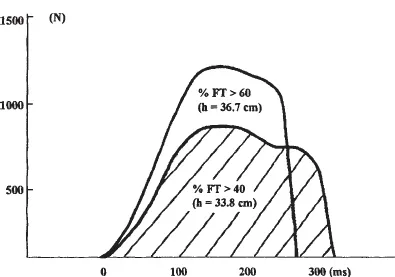

Fig. 4. Average vertical force-time curves for vertical jumps made by two groups of subjects with different muscle-fiber composition on a force platform. The jumps were performed from a starting position with relatively extended knee angle [11].

The importance of the short take-off time can be characterized by comparing schematically the take-off forces between actual ski-jumping and the simulated ski-jumping take-off (Fig. 4). It is interesting to note that ski-jumpers have more favourable isometric-force time curves than the controls (Fig. 2) or, for example, endurance athletes. This may be due to the adaptation...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- First International Congress on Skiing and Science St. Chrisoph a. Arlberg, Austria January 7-13, 1996

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One Biomechanics of Skiing

- Part Two Fitness Testing and Training in Skiing

- Part Three Movement Control and Psychology in Skiing

- Part Four Physiology of Skiing

- Part Five Sociology of Skiing

- Index of authors

- Index of keywords