1

The Georgian Villager in the Soviet Context

It is my intention that this study should have the status of an ethnographic report on a particular village, on domestic roles and relations and the way these are perceived by the villagers. It cannot encompass with great thoroughness and detail an analysis of national government policy, political behaviour towards the state and the nature of the national economy. There is nevertheless, always, a certain inevitability that significant statements must be made about the wider context of a ‘micro-study’, although it would not be feasible to expand on them at length. Furthermore, most British anthropologists are, relatively speaking, unfamiliar with Soviet materials and so more background information should be provided than, for example, is usually necessary in works on rural families in Greece or other countries in the Western world.

Combining my personal views and those from a selection of the literature, this chapter will give an account of some relevant facets of the Soviet system in general. A description of the Georgian villagers’ perceptions of this system will also be given. These will be contrasted, as an interpretation, with the data presented. It will then be possible, in the rest of this work, to comment on the relationship between the villagers’ interpretation of the Soviet system and the observed domestic unit, without begging too many questions.

I recognize a shortcoming in an approach which seeks to contrast villagers’ perceptions with ‘facts’. Paul Stirling, in reference to Turkish villagers, stated that ‘Most villagers’ views of how the administration works are inaccurate’ (Stirling, P., 1966, 290). To make a similar statement, also undoubtedly true, regarding the Soviet villagers, raises a difficulty of a particular kind, although it is only relative. In the Soviet Union data are so hard to obtain on the nature of the administrative system and the real direction of state machinery that contrasts can usually be made only between mere opinions of (largely Western) social scientists and those of the village informants.

A survey of literature on Soviet affairs usually reveals how inevitable it is that the authors’ subjective positions should have more prominence, relatively speaking, than similar works concerning other countries such as Turkey or Greece. On the one hand, this is mainly the result of there being no access available to Western scholars to check minor subjects and statistics, especially at a central level, On the other hand, Soviet scholars themselves are not allowed to publish challenges they may want to make to official statements and statistics. One must also assume that few but the most uncontroversial topics will be covered accurately in official publications. In the majority of cases, too, Western scholars have to do their research in much less favourable conditions than are usually acceptable; for example, Humphrey was only able to spend a few weeks in Buryatiya (Humphrey, C., 1983) and Friedgut one week only in Kutaisi, Georgia, on which to base his work, Community Structure, Political Participation and Soviet Local Government; the Case of Kutaisi (Friedgut, T., 1974). I myself was not allowed to bring all my notes out of the Soviet Union (see Introduction).

If state and political activities, especially centrally, are visible to observers only at a superficial level and the actual mechanics of the way they are articulated cannot be scrutinized, then scholars can publish only informed guesses and pertinent speculations which are probably close to being accurate on ‘how the administration works’. It is only data of this kind which can be contrasted with the perceptions of the villagers I studied. Inherent in my approach, therefore, is an implicit form of ranking: 1) Soviet official information and its interpretation are accessible to all but are often inaccurate; 2) the villagers’ interpretations of the Soviet system are valid for their own world view, but are partly inexact as a description of the system at large; 3) social scientists’ views, including my own, although recognizably biased and limited, are closer to being accurate than the other two.

Throughout the work, my fieldwork experience has led me to choose to emulate Gudeman, who focused on people’s concepts concerning kinship, the domestic unit and their place in society at large. These are better understood as a system of ideas than empirical relations (Gudeman, S., 1976). My criteria for selecting topics for discussion in this chapter have depended on their relevance for achieving a better understanding of villagers’ ideas. An evaluation of their ideas, however, is coloured by my own and other writers’ subjective opinions in a way which should not be overlooked.

(I) Notions Concerning the State

1

The nature of the Soviet state is complex to define and its description varies according to one’s own political approach, as has been pointed out by McAuley (McAuley, M. 1977). Depending on the definition used, of course, it would nevertheless be difficult to define the regime in the 1970s as ‘totalitarian’ (McAuley, M. 1977, 147). The system, however, is ‘dominated by a single highly centralised party, which tolerates no opposition, which directs all the institutions of society, and which has its origins in Marxist-Leninist doctrines and continues to justify all its actions in terms of these doctrines’ (Rigby, T.H., 1981, 3 and 4).

Archie Brown quotes Soviet authors in his discussion of the central role of the party and the nature of the Soviet state. He cites L.Grigoryan and Y.Dolgopolov’s work ‘Fundamentals of Soviet State Law’, where they wrote:

The Theses of the Central Committee for the CPSU for the Lenin Birth Centenary (1970) indicate: ‘The socialist state of the whole people is continuing the cause of the proletarian dictatorship and serving as the organising element in solving the tasks of the building of communism’. Like the dictatorship of the proletariat, it is an instrument of the working people’s will and interests. But the state of the whole people does not express the interests only of the majority of society, but of the whole people. (Grigoryan, L. and Dolgopolov, Y. 1971)

Brown then adds that ‘The argument of Soviet Marxist-Leninist theorists is that Soviet society is socialist and that there can be no conflict of interest under socialism’ (Brown, A., 1974, 18 and 19).

On the one hand, the regime here seeks to control all institutions, and is in the position of having exclusive control over all means of communication and socialisation. Here, ‘Private activities attain—though in varying degrees—public significance, and regulation by the state establishes not only a general framework for these private activities, but also attempts to influence their content’ (Markus, M., 1981, 86). On the other hand, the regime claims to be merely the voice of the whole people and to be fulfilling its will, ‘from below’. It is not surprising that the question of legitimation is so important to study, and with it the role of ideology in the legitimizing activities of the authorities. Stephen White has remarked, ‘Both Western and Soviet commentators have normally agreed that among the most distinctive features of the Soviet political system is the central importance it attaches to ideology’ (White, S., 1980, 323).

To justify both the right of the authorities to rule the country in the way they do and to carry the people with them, the official version of the state’s ideology revolves round two premises taken from Marxist doctrine. The first is that the Soviet Union today is at the stage of socialism, according to the Marx-Engels schema of human progress (Gellner, E., 1975). This is the era of the dictatorship of the proletariat, where there can be no conflict of interests, either between the two officially recognized social classes, the workers and the peasants, or with the ‘social stratum’ of the intelligentsia (Brown, A., 1974). Nor can there be divisions between rulers and ruled, since the so-called rulers, the authorities, are merely carrying out the will of the people. The second tenet is that the Soviet Union is moving, in accordance with the will of the people, towards the stage of communism. That is when whatever vestiges of social classes which still remain will vanish, the state apparatus will disappear and such total harmony and prosperity will reign that all people will live not through what they earn but according to what they need (Marx, K., 1875). So all present efforts, whether economic or other, are said to be aimed at achieving that stage. T.H.Rigby writes, ‘The legitimacy claims of the political system, of those holding office under it, and of the latter’s commands, are validated in terms of the final goal (‘communism’) from which the partial and intermediate goals set by the leadership are allegedly derived and to which individual goals should be subordinated’ (Rigby, T.H., 1982, 12).

So close is this official version of things to the early Bolshevik commitments of the founders of the Soviet state that we must remind ourselves of another aspect of their doctrine. As revolutionaries, they were pledged to creating radical change through modernization programmes of every sort, through transforming social institutions and economic systems, so that Soviet society should be totally different, within a short space of time, from the way it was at the inception of the Revolution. It is important to note here, for the context of this work, that it was thought that such radical change would embrace national cultures so forcefully that national differences within the Soviet Union would, of their own accord, soon be eradicated. Likewise, as has been noted by many authors, the nature of peasant household structure and peasant attitudes were also viewed as malleable and likely to be transformed beyond recognition by the correct socialist policies (see Mitrany, D., 1951: Shanin, T., 1972; Laird, R. and B.L., 1970). Our study of the domestic unit in rural Georgia will highlight some of the areas of failure in the drive for radical change within national and peasant culture.

Today the Soviet leadership still describe themselves as direct heirs of the Revolutionaries, fulfilling the same tasks and committed to the same ideas. After nearly seventy years of Soviet power they reiterate their confirmation that the Soviet state is already socialist and moving towards communism. Any evidence that the criteria for a socialist state are partly absent, as yet, they dismiss as untrue or simply re-label, even under the rubric of ‘glasnost’, as evidence of a few backward pockets of misfortune.

In their environment and everyday life in the Soviet Union, most people do not recognize that they are in the kind of socialist society which has connotations of almost Utopian well-being, of justice, prosperity and harmony. Several authors argue that, faced with such contradictions between official descriptions and actual observations and experiences, Soviet people have naturally become sceptical of the official ideology too (White, S., 1980; Nove, A., 1969; Brown, A., and Gray, J. (eds), 1977). A.Heller remarks that more recently a form of ‘traditional legitimation’ has been resorted to by the authorities whereby ‘With time an imposed or revolutionary system of rule may come gradually to seem the normal order of things’ (Heller, A., 1981). Ferenc Feher claims that the new dominant mode of legitimation in Communist countries is paternalist, where the regime evaluates itself publicly as efficacious or benign (Feher, F., 1981). Rigby, however, also stresses the importance of the fact that ‘The significance for the legitimacy of a regime [is] that its policies and actions be seen to conform with the basic values and beliefs of the society concerned’. He argues that the regime may seek to transform those beliefs and values. On the other hand, he says, it may increasingly conform its actions to established social beliefs and attitudes (Rigby, T.H., 1981, 16– 18).

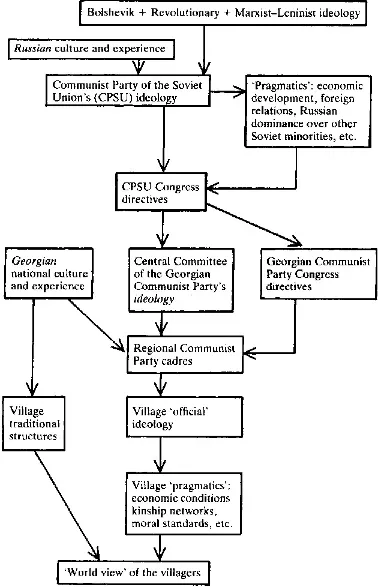

It is at this last juncture, in having to adapt policy, eventually to established social beliefs and attitudes, that the impact of Russian history and culture—as Russian—has been felt in the ideas and orientations of the Soviet regime (see Figure 1.1). This applies in particular to the response of non-Russians. They reinterpret Soviet concepts as Russian, and this is particularly the case in Georgia (Nove, A., 1969). An article providing materials from which this can also be inferred is J.W.R.Parsons’ work, ‘National integration in Soviet Georgia’ (Parsons, J.W.R., 1982, 547–69).

As regards the villagers of Ratcha, their views of the nature of the state and of Soviet official ideology bear little resemblance to what has just been presented above. This is because of two factors: the history and culture of the Georgians, and the paradoxical effects of some Soviet policies themselves.

Although they live in isolated mountain villages, the Ratchuelians have close contacts with Georgian urban centres because of the high rate of migration by family members and kin to the towns. They have always had their own ‘intelligentsia’—local historians, poets and others—who have also tended to reaffirm the precepts of national Georgian culture. Furthermore, as Parsons points out, ‘It is apparent that Georgians consider rural Georgia as the repository of the nation’s cultural heritage, a fact evident not just in the fine arts, in poetry and in prose writing, but also in the considerable body of research into Georgian folklore, dance and music as well as in films’ (Parsons, 1982, 555). They share many attitudes with the more educated sections of urban Georgians.

Relations with the Soviet state, by and large, are viewed by the Georgians as relations between two nations, Russia and Georgia. Incorporation into the Soviet Union of Republics is not understood as participation in a common aim of transforming society into a Communist paradise. Instead, it is seen as the way of maintaining tolerable relations with its most Source: T. Dragadze, 1987 (D. Phil. thesis) powerful and dominant neighbour. Political activity and political consciousness do not focus on issues of socialism or the discussion of alternative political theory and practice. Their real concern is with gaining the best advantages from their inevitable subordination to the Russians in Moscow, as they say, and from the Russian-imposed political and economic system. They also discuss endlessly the problems and strategies of Georgian nationhood for the maintenance of its culture, within the confines of Soviet Russian dominance.

Figure 1.1 The Georgian village in the Soviet system

Source: T. Dragadze, 1987 (D. Phil. thesis)

Attitudes to the Russian authorities themselves have always remained ambivalent, as I said in the Introduction. J.W.R. Parsons reiterates this view:

There is considerable ambivalence in the Georgian attitude towards Russia and the Russians, for whilst in the 19th century Georgians resented tsarist policy towards their country, they appreciated that Russia had made possible their resistance to invasion from Persia and the Ottoman Empire and created the conditions for a revival of the national economy. The majority of Georgian intelligentsia saw their future as linked with that of the Russian people freed from tsarist oppression, and the Georgian Mensheviks insisted on maintaining the union with Russia until their rejection of the October Revolution finally forced them to declare independence. It is an ambivalence that has continued to the present day, for whilst many Georgians may express their hostility towards Russians [although opportunities are very limited], few relish the prospect of an independence that would leave them bordered by Muslim revivalists on one side and the Turkish military on the other. Stability and sixty years of Soviet power have enabled Georgia to acquire a standard of living (and the highest proportion of doctors per capita in the world) far in excess of that existing in Turkey and Iran. (Parsons, J.W.R., 1982, 560)

Severe repressive measures, a powerful army composed entirely of non-Georgians on their territory and the acknowledgment of the relative advantages of Russian as opposed to Muslim dominance have prevented the creation of counter-politics among Georgians. Official ideology, however, has little chance of being assimilated. Nor are th...