- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding the Small Family Business

About this book

It is estimated that family businesses comprise between 60-90 % of all firms in Europe and the United States. This book makes an important contribution to the understanding of small family firms by bringing together a number of key themes in management/organisation studies. Reviewing a range of theoretical approaches, examining key literature and drawing from an international range of primary research, it also points to the future of research in this arena, and indicates how support and policy initiatives may be directed in the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding the Small Family Business by Denise Fletcher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

A rationality discourse in studies of the small family business

1 The scale and nature of family businesses

Paul Westhead, Marc Cowling, David J. Storey and Carole Howorth

Introduction

A key objective for owners of family businesses is to pass their businesses on to the next generation of family members (Morris et al., 1997). Many family business owners are concerned that the fiscal regime, particularly capital taxes, can put at risk the inter-generational transfer of businesses (J.L. Ward, 1987). Policymakers and practitioners can introduce policies that encourage the survival of family businesses. They are, however, reluctant to introduce new policies or change the tax regime without reliable information about the scale, nature and economic contribution of family business activity. There is, therefore, a need for academics, practitioners and policy-makers to carefully define, identify and understand their target group of analysis. Policy-makers are interested in reliable information that indicates whether family businesses report superior levels of performance than non-family businesses (Shanker and Astrachan, 1996). If family businesses were associated with superior business performance than non-family businesses, this would be a powerful argument for lowering capital taxes, because of the benefits to the wider economy. Further, if the transfer of businesses between generations of family owners were to lead to enhanced performance (i.e. faster sales revenue and employment growth), then it could be argued that inter-generational transfers are in the interests of the national economy as well as family business owners. If family businesses transferred from one generation to the next performed no better, or worse (i.e. ‘clogs to clogs in three generations’), then there is no clear case for seeking to lower/abolish capital taxes.

Of particular relevance to policy-makers and practitioners is reliable information relating to the following questions:

- Is the reported scale of unquoted family company activity influenced by the family business definition selected?

- What proportion of unquoted companies are family businesses?

- Are unquoted family companies over-represented in older business age bands?

- Are unquoted family companies over-represented in small employment size bands?

- Are unquoted family companies over-represented in lower sales revenue size bands?

- Are unquoted family companies over-represented in any industrial sectors?

- Are unquoted family companies over-represented in any regions?

- Do family businesses report superior levels of financial performance than non-family businesses?

- Are family businesses more likely to stress non-financial performance objectives than non-family businesses?

In this chapter, it is emphasised that the scale of the family business phenomenon is definition dependent. Demographic differences as well as similarities between family and non-family businesses are discussed. Evidence from studies focusing upon the performance of family and non-family firms is also reported. In the final section, conclusions and implications for policy-makers and practitioners are discussed alongside directions for additional research attention.

Family business definitions

There is a lack of consensus surrounding the theoretical and operational definition of a family firm (Handler, 1989b; Litz, 1995, Chua et al., 1999). Researchers have frequently used four key issues when defining family firms. First, whether a single dominant family group owns more than 50 per cent of the shares in a business (Donckels and Fröhlich, 1991; Cromie et al., 1995). Second, whether members of an ‘emotional kinship group’ perceive their firm as being a family business (Gasson et al., 1988; Ram and Holliday, 1993b). Third, whether a firm is managed by members drawn from a single dominant family group (Daily and Dollinger, 1992, 1993). Fourth, whether the company had experienced an intergenerational ownership transition to a second or later generation of family members drawn from a single dominant family group owning the business (Gasson et al., 1988). In addition, some researchers have considered multiple conditions when defining family firms.

Studies in which the numerical dominance of family businesses is greatest have used the widest definitions, by asking respondents whether their business satisfied one specific criterion. Westhead and Cowling (1998) argue that two or more of the above elements in combination need to be considered when identifying family businesses. It is, however, appreciated that there is no single definition of a family business that is widely acceptable.

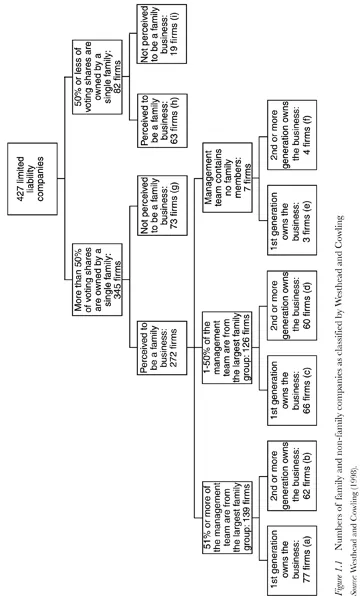

Using the four criteria highlighted above, several operational definitions of an independent unquoted family company were identified by Westhead and Cowling (1998) as follows.

- The company was perceived by the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman to be a family business (categories a, b, c, d, e, f and h combined in Figure 1.1).

- More than 50 per cent of ordinary voting shares were owned by members of the largest single family group related by blood or marriage (categories a, b, c, d, e, f and g combined).

- More than 50 per cent of ordinary voting shares were owned by members of the largest single family group related by blood or marriage and the company was perceived by the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman to be a family business (categories a, b, c, d, e and f combined).

- More than 50 per cent of ordinary voting shares were owned by members of the largest single family group related by blood or marriage, the company was perceived by the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman to be a family business and one or more of the management team was drawn from the largest family group who owned the company (categories a, b, c, and d combined).

- More than 50 per cent of ordinary voting shares were owned by members of the largest single family group related by blood or marriage, the company was perceived by the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman to be a family business and 51 per cent or more of the management team were drawn from the largest family group who owned the company (categories a and b combined).

- More than 50 per cent of ordinary voting shares were owned by members of the largest single family group related by blood or marriage, the company was perceived by the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman to be a family business, one or more of the management team were drawn from the largest family group who owned the company and the company was owned by second generation or more family members (categories b and d combined).

- More than 50 per cent of ordinary voting shares were owned by members of the largest single family group related by blood or marriage, the company was perceived by the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman to be a family business, 51 per cent or more of the management team were drawn from the largest family group who owned the company and the company was owned by second generation or more family members (category b).

Figure 1.1 Numbers of family and non-family companies as classified by Westhead and Cowling Source: Westhead and Cowling (1998).

Westhead and Cowling used these stated family business definitions to measure the scale of family business activity. Data were gathered from a stratified random sample (by broad industrial categories and by standard region) of independent unquoted companies that were at least ten years old located throughout the United Kingdom. Evidence from a postal survey of 427 respondents was analysed.

In Table 1.1, the 427 independent unquoted companies surveyed by Westhead and Cowling were subdivided with regard to majority share ownership of ordinary voting shares, perception by the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman of being a family business, family members involved in the management team and the generation of family business ownership. Table 1.1 shows the proportion of businesses classified, as ‘family businesses’, is highly sensitive to the definition used. Using the widest definition 81 per cent of companies sampled could be viewed as ‘family businesses’. Whilst using the narrowest definition, this fell to only 15 per cent.

All four elements are potential influences upon definitions of what constitutes a family business. Some elements, however, are more central than others. While it is important for the Chief Executive/Managing Director/Chairman to view the enterprise as a family business, i.e. definition (1), this can be regarded as a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition. If it were a sufficient condition, then the definition would be totally subjective and, as outsiders, we would have no clear idea upon what basis the categorization was made. Broad all-embracing definitions of a family company, such as definition 1, have, however, been questioned on the grounds that they are too inclusive. As a result, definition (1) cannot be regarded as the most appropriate definition. Similarly, definitions with multiple conditions, such as those associated with definitions (6) and (7), have been questioned on the grounds that they are too restrictive. It may be overly restrictive to require that all family businesses have to be at least ‘second generation businesses’.

Table 1.1 Numbers of surveyed family and non-family unquoted companies in the United Kingdom

The elements that most closely encapsulate the concepts of a ‘family business’ are ‘perception’, ‘share ownership by family members’ and ‘management of the business by family member’. Definitions (3), (4) and (5) in Table 1.1 best incorporate these concepts, with definition (3) being the most expansive and definition (5) being more restrictive. Westhead (1997) argued that ‘ownership’ rather than ‘family management’ is the crucial family element that distinguishes family companies from non-family companies. As a result, Westhead favoured definition (3) rather than definitions (4) and (5), which, in fact, are very similar.

Characteristics of family businesses compared with non-family businesses

In this section, demographic differences between family and non-family firms are discussed with regard to business age and size, principal industrial activity of the business and the location of the business.

Business age

The Stoy Hayward (1992) survey of family and non-family unquoted and quoted companies in the United Kingdom found family companies were longer established than non-family companies. With regard to several family firm definitions, Westhead and Cowling (1998) also detected that independent unquoted family companies were much more likely to be older than non-family companies.

Business size

Daily and Dollinger (1993) found professionally managed independent manufacturing firms with less than 500 employees in the United States were significantly larger in terms of number of employees than family-owned and family-managed firms. Furthermore, Donckels and Fröhlich’s (1991) study focusing upon independent manufacturing firms with less than 500 employees in eight European countries noted the highest proportions of family firms were found in the smallest employment size bands. Cromie et al. (1995) and Westhead and Cowling (1998) also detected that Irish and British family firms were smaller in terms of employment size and sales turnover than non-family firms.

Principal industrial activity of the business

In the United States, Reynolds (1995) found new family firms were less likely to be engaged in manufacturing and business services. Stoy Hayward (1992) detected that a larger proportion of service businesses were family companies in the United Kingdom. Gasson et al. (1988) also noted the majority of farms in the United Kingdom are family businesses. More recently, Westhead and Cowling (1998) detected that family businesses were more likely to be over-represented in agriculture, forestry and fishing as well as in the distribution, hotels and catering industrial sectors. Family businesses were, however, under-represented in the banking, financing, insurance and business services sectors.

Location of the business

Westhead and Cowling (1998) explored w...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Routledge Studies in Small Business

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Introduction: ‘Family’ as a discursive resource for understanding the small family business

- Part I: A rationality discourse in studies of the small family business

- Part II: A resource-based discourse in studies of the small family business

- Part III: A critical discourse in studies of the small family business

- Bibliography