Section 1.

Analysing the profiles

The idea of producing lesson profiles is to try and find a way of ordering all the different events that go on during a lesson. It is a way of producing a coded reconstruction of classroom activities so that we can begin to talk about what goes on with some common reference to perception and understanding. Having got into the habit of thinking of lessons as a structured sequence of events it is not always necessary to produce the profile—it is intended as a means of understanding events rather than as an end product in itself.

Having established this approach we want to introduce some ideas that we found useful in observing lessons. We want to work towards a descriptive language which we can use to explore how lessons are at the same time both similar and different. The collection of ideas we are going to introduce is not an absolute one—the ideas are open to discussion, extension, addition and change—but we think it makes a useful starting point.

1.

FORMAL AND INFORMAL SITUATIONS

If you look through a few lesson profiles you will notice that some of the changes in activity are marked quite dramatically. Usually these involve the teacher attracting the attention of the class in some way, perhaps at the start of the lesson or after an episode of practical work. Different teachers have different methods for managing these overall changes in group activity— consider this rather unusual method from a teacher’s account of her infants’ class:

There is, however, in the following pages, something left out: I didn’t talk about discipline. An overall reflection of that work in the prefab could well give teachers a valid suspicion of chaos with the freedom of movement and talk. But chaos has a certain quality of its own that none of us allows in teaching; chaos presupposes a lack of control, whereas control was my first intention. As my inspector at tha. time observed, ‘Discipline is a matter of being able to get attention when you want it.’

I often wanted attention and I wanted it smartly. And I trained the children in a way that is new only, maybe, in degree. Most teachers have some simple way of calling a room to attention; some use a bell, some rap a ruler, and most, I should think, use their voices. But where the sounds of learning and living are allowed in a room, a voice would need to be lifted and sharpened and could be unrepresentative of a gentle teacher; so, predictably, I used the keyboard. No crashing chord, no alarming octave, but eight notes from a famous master; the first eight notes from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. What was good for him was good enough for me, since, whereas he demanded attention for the rest of the symphony from several thousand people, I wanted it for only a sentence.

At the sound of these notes I trained the Little Ones, whatever they were doing, to stop and look at me. I trained them this way from necessity but in time I did so from pleasure. And never through those vital years in the heaving prefab did I cease to be impressed at the sudden draining away of sound, like blood from a face, into the utmost silence. And not just silence, but stillness: every eye on me, every hand poised; an intensity of silence born from sound…

For me to speak and be heard by all.

Some simple direction, some needed advice indisputably heard by all. How I polished this instrument of attention! My most valuable too, the most indispensable of them.

For it is not so much the content of what one says as the way in which one says it. However important the thing you say, what’s the good of it if not heard or, being heard, not felt? To feel as well as hear what someone says requires whole attention. And that’s what the master’s command gave me—it gave me whole attention. You might argue, ‘But how could a child at the far end of a room full of movement, talk and dance hear eight soft single notes?’ Any teacher could answer that. The ones near the piano did. And they‘d touch the others and tell the others until the spreading silence itself would tell, so that by the time the vibration of the strings had come to rest, so had the children. Those silences and those stillnesses, I’ll remember them…for more than seven years after.

Sylvia Ashton-Warner, Teacher (Penguin, 1966).

This account implies two quite different kinds of teaching situation for the teacher in this class. One where there is ‘freedom of movement and talk’ and the teacher is relatively unobtrusive; the other where there ‘is not just silence, but stillness; every eye on me, every hand poised’. It is the distinction between these two quite different kinds of classroom situation we consider most basic in understanding the profiles and which we want to explore in some detail.

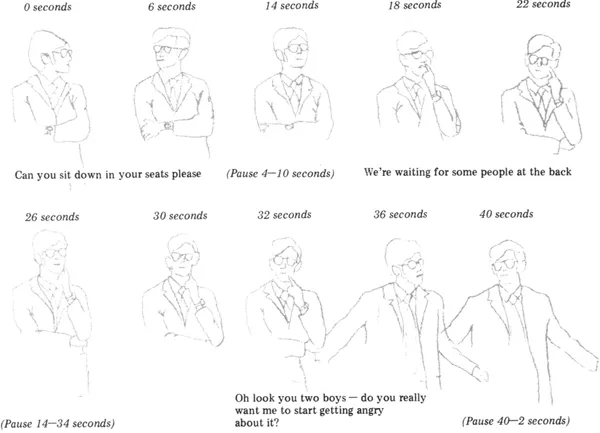

A useful point to start looking at this difference is to look at the transitions between the situations, rather than at the situations themselves. To look at what Sylvia Ashton-Warner calls ‘getting attention’.

Getting the attention of the class

Towards the end of the science practical lesson. The teacher walks to the front of the room and stands in front of the demonstration bench. He waits for the class to notice he is waiting for them to notice him. Gradually the ripple of attention spreads.

For a similar example see the film School mentioned at the back of the ‘Resource book’ at the start of Mrs Dohson’s first lesson with the class.

Although established teachers usually have some salient action for ‘attracting the attention of the class’, beginning teachers soon learn that the effectiveness of these actions is not dependent on any simple learning theory. The children do not respond to the signal like Pavlov’s dogs in a simple ‘stimulus-response’ manner, but see the signal only in the context of that teacher’s total performance. Another teacher simply mimicking the action cannot guarantee the same response. Consider this extract from Jacob Kounin’s research study:

Concern with discipline techniques may be as prevalent as it is because misbehaviour does stand out perceptually. While observing a classroom, one is more likely to notice a child who is throwing crayons than a child who is going about the business of writing in his workbook. And a teacher who is reprimanding a pupil is more likely to be noticed than when she is listening to a child read. Furthermore, there is no questioning the fact that one may observe a desist technique that is effective as well as observe a desist technique that is ineffective, especially if these occur in different classrooms. Thus, we have seen Teacher A walk to the light switch and flick the lights on and off two times as a signal for the children to be quiet and listen to her. It worked. The children immediately stopped talking or doing whatever they were doing, and sat in a posture of atte...