- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions

About this book

Illustrating the effect of class relationships upon the institutionalizing of elaborate codes in the school, the papers in this volume each develop from the previous one and demonstrate the evolution of the concepts discussed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions by Basil Bernstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Changes in the moral basis of schools

Chapter 1

Sources of consensus and disaffection in education1

I want to talk about some of the consequences of education where the school acts as a major source of social, occupational and cultural change. It is well known that the school transforms the identities of many of the children: transforms the nature of their allegiances to their family and community, and gives them access to other styles of life and modes of social relationships. I am going to present an analysis of being a pupil as this role is formed and transformed by the school. The child’s response to the school is likely to transform the way in which he thinks and feels about his friends, friends, his community, and society as a whole.

I shall first examine the culture of the school, particularly of the secondary school, and I shall try to establish what this school culture is transmitting to the pupils. Second, I will classify different kinds of family settings in terms of a family’s perception of the school culture; how they regard it, see it and understand it. Third, I shall consider various ways in which a pupil may be involved in the school and I shall try to indicate how the culture of the school and the form of its transmission may shape the child’s involvement in his role as pupil. Finally, I shall consider some consequences both for the child and for society of these various involvements in the role of pupil. The major factors affecting the behaviour of pupils in school are four: the family setting and social origins of the child, the age group or friendship patterns of the child, the school itself, and the pupil’s perception of his occupational fate. Any analysis of the pupil’s involvement in his role must take into account these four factors—family, age group, school and work—and show the relationships between them. The analysis should hold irrespective of the type of secondary school—grammar, secondary modern or comprehensive—and, in principle, should be capable of extension to other countries; in fact wherever a school is an agent of cultural change.

First, I shall consider the culture of the school and the kind of behaviour the school transmits to the pupil. What are the procedures, practices and judgments that the school expects the pupil to master? There are two distinct, but in practice inter-related, complexes of behaviour which the school is transmitting to the pupil: that part concerned with character training and that part which is concerned with more formal learning. On the one hand, the school is attempting to transmit to the pupil images of conduct, character and manner; it does this by means of certain practices and activities, certain procedures and judgments. On the other hand, the school is transmitting to the pupil facts, procedures, practices and judgments necessary for the acquisition of specific skills: these may be skills involved in the humanities or sciences. These specific skills are often examinable and measurable by relatively objective means. The image of conduct, character and manner is not measurable in the same way. Among the staff there may be a fair degree of agreement about the learning,2 but there is more room for doubt and uncertainty about the image of conduct, character and manner which the school is trying to transmit.

I propose to call that complex of behaviour and activities in the school which is to do with conduct, character and manner the expressive order of the school, and that complex of behaviour, and the activities which generate it, which is to do with the acquisition of specific skills the instrumental order.

The relations between these two orders are often a source of strain within the school. The instrumental order may be transmitted in such a way that it distinguishes sharply between groups of pupils. Children may often be streamed off from each other in terms of their ability, in order to assist the development of specific skills in some. Thus the instrumental order of the school is potentially and often actually, divisive in function. It is a source of cleavage not only between pupils, but also between staff (depending upon the subject taught, the age, sex, social class and stream of the pupils).

The expressive order attempts to transmit an image of conduct, character and manner, a moral order which is held equally before each pupil and teacher.3 It tends to bind the whole school together as a distinct moral collectivity. The more the instrumental order dominates schools in England, the more examination-minded they become and the more divisive becomes their social organization. The greater the emphasis on this type of instrumental order, the more difficult it is for the expressive order to bind and link all the pupils in a cohesive way. It is quite likely that some pupils who are only weakly involved in the instrumental order will be less receptive to the moral order transmitted through the expressive order. In this situation, the children may turn to an expressive order which is pupil-based, and anti-school. It is also likely that a strong involvement in the instrumental order may lead, under certain conditions, to a weakening of the pupil’s involvement in the expressive order and the values it transmits.

There are a number of influences which affect the form and the content of the instrumental order (see Appendix A). Major influences are, of course, the economy and the class structure. However, it is likely that any change in the school leaving age or any change in the length of the average educational life will have major implications for both the form and contents of the instrumental order.4 This is too large an issue to be discussed in this paper.

The instrumental order itself may be unstable when society is undergoing rapid technological change. Different subjects may be introduced into the curriculum and some may lose their status. There may also be a change in the means through which the instrumental order is transmitted, in the teaching methods, and this may lead to instabilities within the school.

The expressive order of the school is legitimized by notions of acceptable behaviour held outside the school, but these notions of acceptable behaviour may not be equally held by all groups within a society. This may be complicated by the fact that in a fluid, changing society, the very image of conduct, character and manner, the moral order itself, may be unclear and ambiguous. There are at least two sorts of strain in a school’s expressive order; first, the moral order may not be acceptable to certain groups within the school, and, second, despite the clarity of the image within the school, the image outside the school may be ambiguous. The weakening of the school’s expressive order is likely to weaken the school’s attempt to transmit behaviours working for cohesion between staff, between pupils, and between pupils and staff.

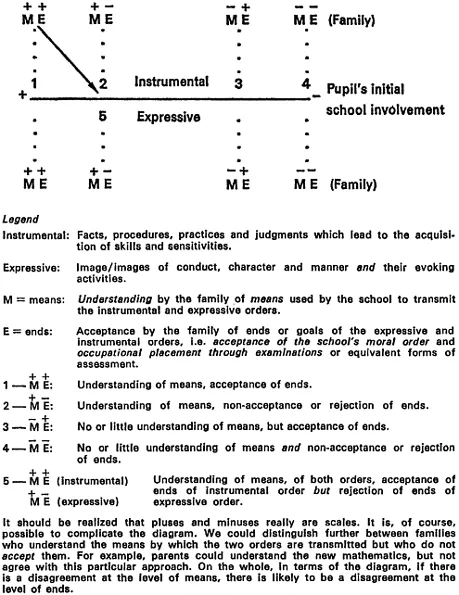

So much for a very brief discussion about these twin aspects of the school. (A more extensive account will be found in Bernstein et al., ‘Ritual in education’, 1966). We shall now present a framework for analysing the pupil’s initial involvement in the school. We shall do this by means of a classification of families. We shall classify families according to their understanding of the means whereby the expressive and instrumental orders are transmitted and their acceptance of their ends (i.e. their goals). (See Figure 1.1.)

In Figure 1.1 there is a thick black line, at one end of which there is a negative sign and at the other end of which there is a plus sign. This represents the involvement of the pupil as this is initially affected by the family. The child at position 1 is highly involved in the school, and in both orders. If he is initially at position 4, then the situation is more difficult both for the child and for the school. If a family understands the means whereby the instrumental order is transmitted (the day-by-day procedures involved in the acquisition of specific skills) then the parents can help to support the child at the level of means. This does not mean that the family accepts the goals of the instrumental order. Similarly, a family may understand the means whereby the expressive order is transmitted (the day-by-day procedures whereby the moral order of the school becomes available to the child) but this does not mean that the family accepts the goals or ends of the expressive order. If a family accepts and understands the means and the ends of both of these orders, then the child would be at position 1. Other things being equal, a child from such a family starts off initially highly involved as a pupil. This is quite likely, but not necessarily, to be a middle-class family.

Let us take position 2. This refers to the family which understands the means whereby these two orders are transmitted, but it does not accept the ends. It does not accept, for example, the examination structure, or the necessity of the linkage between education and occupation, or the image of conduct, character and manner. It may hold a different concept of learning, and it may not accept, say, the grammar school concept of appropriate conduct. We can expect here a clash between home and school at the level of ends, which may also lead to a clash at the level of means. A child from such a family would, compared to position 1, have a reduced involvement and so we have placed him at position 2.

Position 3 is a very important one. This is a family which accepts the ends of the instrumental order, but has little understanding of

Figure 1.1 The family’s effect on the pupil’s involvement in school

the means used to transmit it. Similarly, it accepts the ends of the expressive order, but has no idea how, in fact, this order is transmitted. The family wants the child to pass examinations, to get a good job, and also to conform to a standard of conduct often different from the one the family possesses. This is often an aspiring working-class family. For such a family, the procedures of the school are often a closed book. This makes for an extremely difficult position for both the family and the child, for the family is likely to deliver the child to school and fail to support him appropriately in matters of learning and adjustment. Consequently, the child’s involvement is likely to be relatively more difficult. What must it be like to be a parent if you are insulated from your child in this way? What must it be like to be a child unable to share his school experience with his family? This is extremely painful for the parents, and for the child. Here the school is driving a wedge between the role of the child in his family and his school role. I am not suggesting this goes on in all schools; I am saying it is a possibility in this situation of position 3.

Position 4 is where the family is very negative and uninvolved in both the means and the ends of the two orders of the school. These are families in England found more often in what Newsom calls ‘the slum and problem areas’. The child’s initial involvement in the school from this point of view is likely to be very weak.

There is a further position of interest. This is the case of a family which understands the means by which the instrumental order is transmitted, and accepts the ends—occupational placement of the child—but it is negative towards the expressive order because it feels that the school’s image of conduct, character and manner may carry the child away from the family and the local community. This family would like the child to get on, but is uneasy of the social consequences. This family is ambivalent and the child is likely to have mixed feelings, so his initial position is likely to be position 5.

Earlier we said that the classification could be complicated if we considered situations where a family un...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Changes in the moral basis of schools

- Part II Changes in the coding of educational transmissions

- Index