eBook - ePub

The Tutu Archaeological Village Site

A Multi-disciplinary Case Study in Human Adaptation

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Tutu Archaeological Village Site

A Multi-disciplinary Case Study in Human Adaptation

About this book

Excavations at the Tutu site represent a dramatic chapter in the annals of Caribbean archaeological excavation. The site was discovered in 1990 during the initial site clearing for a shopping mall in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. The site was excavated with the assistance of a team of professional archaeologists and volunteers. Utilizing resources and funds donated by the local scientific communities, the project employed a multidisciplinary sampling strategy designed to recover material for analysis by experts in fields such as anthropology, archaeology, palaeobotany, zooarchaeology, bioarchaeology, palaeopathology and photo imaging. This volume reports the results of these various applied analytical techniques laying a solid foundation for future comparative studies of prehistoric Caribbean human populations and cultures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Tutu Archaeological Village Site by Elizabeth Righter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Background of research and sample collection at the Tutu site

Elizabeth Righter

ENVIRONMENTAL BACKGROUND

Physical setting

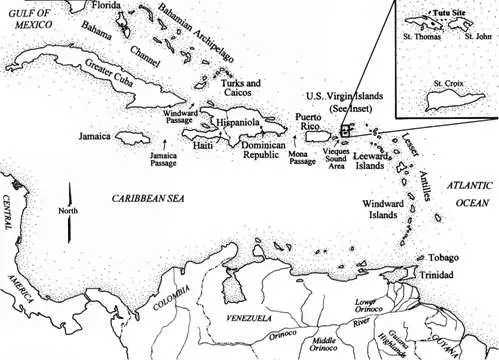

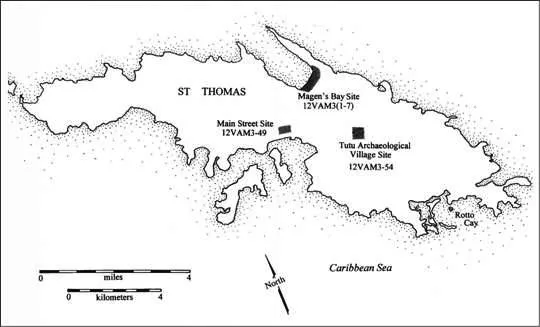

The Tutu Archaeological Village site is nestled in an inland valley, about 1.75 km from the nearest seacoast, on the eastern end of the island of St Thomas, US Virgin Islands. St Thomas is one of a chain of islands that extends along the eastern edge of the Caribbean Sea and stretches from Trinidad off the northern coast of South America to the western end of Cuba (Figure 1.1). Located about 55 km east of Puerto Rico (18° 20’ N, 64° 56’ W), St Thomas is geologically more closely related to this island than to islands of the Lesser Antilles to the east and southeas,; and is, therefore, usually included among islands of the Greater Antilles. St Thomas (Figure 1.2; Figure 1.3) is about 5 km wide at its widest point, 24 km long, and has an area of about 83 km2. In form, St Thomas consists of a long east—west ridge, rising to about 500 m at its highest point, with numerous fast-descending spurs to sea level. Little level ground is present, except at bay heads, where run-off from sharply dissected ravines has created gently sloping land; in summit areas generally above 300 m in elevation; and in the valley of Turpentine run, where the Tutu site is located. Soils of St Thomas are mostly thin and rocky, particularly on the coast and steep ridge slopes (Pearsall, 1997).

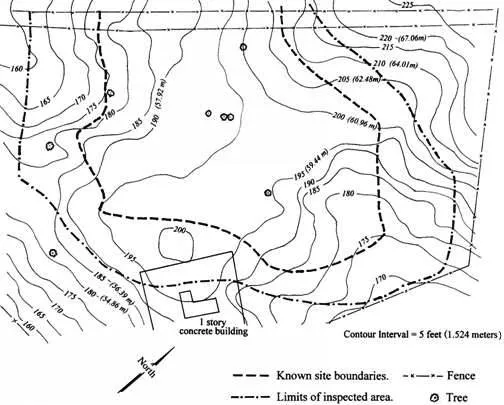

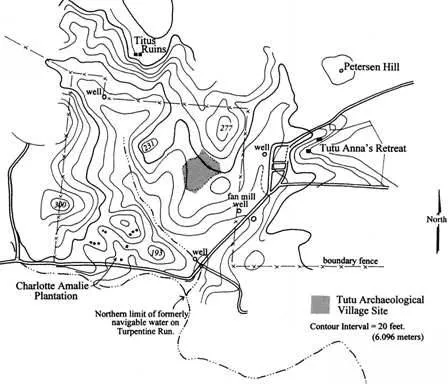

When discovered, the Tutu site (Figures 1.3, 1.4) comprised about 2.20 hectares of predominantly flat pasture land at the base of an amphitheater-shaped hollow, surrounded by low hills; today the site is a shopping mall. In 1990, a branch of Turpentine run (a currently intermittent water course known locally as a “gut”) extended along the western and southwestern boundaries of the site (Figure 1.5) and drained to the south shore of St Thomas, emptying into what is today known as the Mangrove Lagoon (Introduction: Figure 3). In the past, tributaries of this gut also extended along the northeastern, eastern and southeastern boundaries of the site. For the prehistoric inhabitants of the Tutu site, this location offered many advantages, including flat land; immediate access to fresh water; a continuously blowing trade wind; a protected defensible position; fertile soil; access to large trees for house and canoe building; and access to the coast via a major stream. In addition, except from certain vantage points on high ridges to the northwest and from a few locations along a low ridge to the northeast, the site was hidden from view by land or sea.

Colonial and modern land uses in the surrounding hills and valleys of Tutu, construction of a dam on the western branch of Turpentine run, and diversion of the eastern branch have altered the ground water patterns in the vicinity of the site (Geraghty & Miller, 1993). It is probable that, in the prehistoric past, Turpentine run was a continuously flowing stream (righter, 1995). In 1991, the author and John Davis, of the Soil Conservation Service, conducted a visual survey of the presently greatly altered stream bed, and concluded that, prehistorically, the run may have been navigable from its mouth to a point about 0.60 km southeast of the Tutu site (Figure 1.5). As well as providing access to more open waters between St Thomas and islands to the east and west, the Mangrove Lagoon was rich in marine resources and must have been a primary habitat exploitation area. Certainly, the abundance of marine resources recovered from midden deposits at the site indicates that the inhabitants of the site had access to and made good use of the sea.

Figure 1.1 Caribbean island archipelago, showing location of St Thomas and the Tutu site in relation to the Greater and Lesser Antilles (graphic by Julie Smith).

Figure 1.2 Map of St Thomas, USVI, showing the Tutu site in relation to the Magens Bay and Main Street sites (graphic by Julie Smith).

Terrain

The following descriptions pertain to the site when it was discovered in 1990 and before it was massively altered by earth moving related to mall development. The Tutu site was a flat-topped ridge in a river valley, with elevations ranging between about 56 m and 63 m above mean sea level (amsl) (Figures 1.4, 1.5). On the eastern and western sides of the ridge, the land sloped to the meet the banks of the Turpentine run’s tributaries; and, beyond the northern portion of the site, the land rose steeply to a hilltop outside the mall property. On the southern end of the site there was a small rise which concealed the prehistoric site from view from the south. Adjacent to the southeastern edge of the site a house had been built on a small knoll which was little altered from its configuration on an historic 1918 map (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Map showing the location and topography of the Tutu site c. 1918, prior to major development on the island of St Thomas and prior to disturbances to the Tutu site (adapted from US Coast and Geodetic Survey Map No. 3771, US National Archives, Washington, DC).

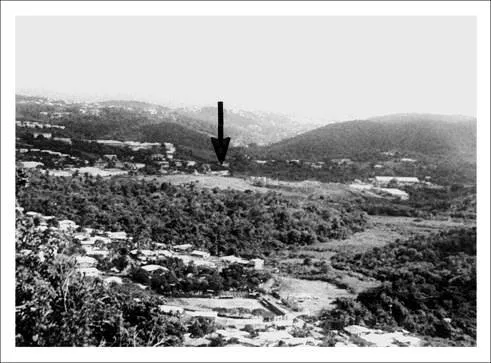

Figure 1.4 Overview of the Tutu site (arrow), looking south from a ridge to the north (photograph by Elizabeth Righter).

Climate and rainfall

The climate of St Thomas is maritime tropical (rivera, Frederick, Farris, Jensen, Davis, Palmer, Jackson & McKinzie, 1970: 73). Throughout the year, daytime high temperatures usually range between about 87°F during the summer months and 80°F in the cooler winter season. Temperatures almost never get below 67°F at night, and rarely get above 90°F in the hottest months, August through October, when the trade winds lessen (Pearsall, 1997).

Trade winds prevail from the northeast, east and southeast throughout the year and wind velocity varies daily. A velocity of more than 24 kph is more common in winter than in other seasons (rivera et al., 1970: 73). Windbreaks are required to protect crops and young trees in open flat areas like the Tutu site; and the site’s prehistoric inhabitants apparently also felt the need to construct screens or fences to channel the wind (Chapter 12). In the Virgin Islands, rainfall generally averages between 16.53 cm (42 in.) and 17.71 cm (45 in.) per year (Bowden, Fischman, Cook, Wood & Omasta, 1970; Eggers, 1879; Pearsall, 1997; Sleight, 1962). Normally there are two rainy seasons, one in May and June, and another more extensive season in the month of November. February through April are the driest months. In general, the combination of strong trade winds and the sharp east—west mountain ridge of the island leads to a pattern of low rainfall on the eastern and southern portions of the island and moister conditions on the northern and western sides. In some areas of the island, moisture lost through evaporation, and transpiration rates, exceed the average annual rainfall; and periods of drought occur almost every year. The pattern of drought varies within the boundaries of an island, and from island to island; and, while portions of one island are undergoing the hardships of severe drought, a neighboring island may be green and lush (Pearsall, 1997).

Historically, the pattern of tropical storms and hurricanes also has been irregular. Normally occurring during the months between June and November, two or three major hurricanes can pass over St Thomas within a 6-year period; followed by as many as 40 years without a major storm. Hurricane damage includes negative impacts to the coral beds and terrestrial wildlife of the island. Several years are required for restoration of healthy coral communities to sustain populations of reef fish; replenishment of popular food sources such as the marine gastropod, Cittarium pica; and return of terrestrial animals such as birds and the insect life that sustains them. Large trees are often truncated, removing the upper canopy; and trees, shrubs and other plants are either killed or denuded of leaves, resulting in a lack of relief from the sun and parched soils during the hot dry months that follow the hurricane season. Impacts of drought and hurricanes, when they occurred, must have affected the lives of the inhabitants of the Tutu site, and it is not difficult to imagine abandonment of the site for several years, as a result of such natural phenomena (Pearsall, 1997).

Site vegetation

The forests of St Thomas were cut during the Colonial period, and the vegetation of St Thomas today is manipulated by humans (Pearsall, 1997). reconstruction of past vegetation patterns, based partially on studies of remnant vegetation in Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and other Caribbean islands, indicates that the vegetation of St Thomas today bears little resemblance to that of the prehistoric period (Pearsall, 1997).

Figure 1.5 Contour map of the Tutu site and surrounding area. Information obtained from a pre-1990 survey map by V.I. Engineering (rendered by Julie Smith).

The Tutu site today lies within the croton, acacia terrestrial vegetation zone; and there is indication that Croton sp. and cf. Acacia spp. also were present in the prehistoric environment of the Tutu site (Chapter 2). During 1991, a brief botanical survey of the Tutu site and its environs was conducted by the author and Ms Toni Thomas, botanist at the Extension Service of the University of the Virgin Islands. At the time, the few trees that had existed on the site (Figure 1.3) had been cut and burned, but on the southwestern fringe, several large Melicoccus bijugatus (genip) trees were still standing. re-vegetated portions of the site and areas of remaining pastureland could be characterized as disturbed shrubland,;possibly former woodland. Noted were grasses and small secondary growth species, including Mimosa pudica (locally known as creechy-creechy); Croton spp. (maran); Jatropha gossypifolia (physick nut); Leucaena leucocephala (tan-tan); and patches of Panicum maximum (Guinea grass). Small trees included Crescentia cujete (calabash); Tababuia heterophylla (pink cedar); and Acacia tortuosa (cassia).

Site fauna

Animals observed on the Tutu site prior to and during the archaeological investigations were limited to Bos sp. (cattle); Ameiva exul (ground lizards); Anolis spp. (anoles); Iguana iguana (common iguanas); Colubridae (non-poisonous snakes); Eleutherodactylus sp. (frogs), some of which seemed to appear spontaneously in mud puddles after rainstorms; a number of birds including Charadrius vociterus (kildeer), Buteo jamaicensis (redtailed hawk), Amazona vittata (Puerto rican parrot); Columbidae (pigeons); Falco peregrinus (peregrine falcon); and songbirds. Also observed were insects, including a variety of spiders, hornets, ants, crickets, mosquitos and butterflies. It is likely that Gecarcinidae (land crabs), and mammals such as Herpestes auropunctatus (mongoose), Mus musculus (house mouse), rattus norvegicus and rattus rattusfrugivorus (Norway and black rat) and Artibeusjamaicensis (fruit bat), also were present at the site (personal communication, Amy Dempsey, Bioimpact, 1999; Lundberg, 1989: 30).

Geology and soils

In 1983, Gerahty & Miller (1993) conducted a geologic survey in the environs of the Tutu site, and, in particular, obtained information from outcrops exposed on the northeast side of the new shopping mall. In the upper basin of the Turpentine run valley, they found thin alluvial and colluvial deposits, varying in thickness between 0 and 6.16 m. Sediments consisted of unconsolidated, unstratified poorly sorted mixtures of clay, silt, gravel, cobbles and boulders transported from the upper valley and foothills by gravity and flash floods.

Underlying the alluvium/colluvium was a moderately weathered, fractured volcanistic rock in which the original rock components had been partially replaced by clay, chlorite and oxide minerals. This rock was a grey to greenish grey volcanic andesitic tuff and breccia with a finegrained matrix and occasional clasts ranging in diameter between 1 cm and 5 cm. Visible mineral grains in the matrix included plagioclase, epidote, pyroxene, hornblende and chlorite. It was in decomposed soils of this type that the majority of features at the Tutu site were preserved.

Underlying the finer grained tuffs and breccias were a poorly sorted breccia, slump blocks, and cobbles up to 20 cm in diameter. These deposits were compositionally similar, with the primary difference between lithologies being grain size. These rocks weathered to a very weak, foliated, clay-rich mineral, which contained almost entirely alteration minerals such as kaolinite, sericite, chlorite and calcite.

Iron staining and thin calcite veins, common along fracture lines that were observed by Gerahty & Miller (1993), also were present in exposed areas of the Tutu archaeological site. Also observed were light brown to tan, sandy to clayey silts of fractured and highly weathered saprolite. Intrusive diorite, a coarse-grained rock composed mainly of sodic plagioclase and hornblende, with variable amounts of quartz, biotite and/or pyroxene, also was found near the Tutu site. Samples obtained were a very dense, dark green to black rock matrix with visible, abundant plagioclase and pyroxene phenocysts (large and well-shaped crystals). The diorite contained abundant, thin veins of calcitic mineral throughout the rock matrix. Along with some imported materials, occupants of the Tutu site used many of the locally occurring rocks and minerals to manufacture beads, tools and other artifacts.

Soils of the Tutu site belong to the Cramer series of the Cramer Isaa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Introduction to the series

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Background of research and sample collection at the Tutu site

- Chapter Two: Analysis of charred botanical remains from the Tutu site

- Chapter Three: Phytolithic remains from the Tutu site

- Chapter Four: Faunal remains from the Tutu site

- Chapter Five: Tutu pottery and ceramic chronology

- Chapter Six: Investigation of ceramic variability at the Tutu site through acid-extraction elemental analysis

- Chapter Seven: Biological adaptation in the prehistoric Caribbean: Osteology and bioarchaeology of the Tutu site

- Chapter Eight: The Tutu teeth: Assessing prehistoric health and lifeway from St Thomas

- Chapter Nine: Trace element analyses of skeletal remains and associated soils from the Tutu site

- Chapter Ten: Bone isotopic analysis and prehistoric diet at the Tutu site

- Chapter Eleven: Flaked stone artifacts from the Tutu site

- Chapter Twelve: Post hole patterns: Structures, chronology and spatial distribution at the Tutu site

- Chapter Thirteen: Site analysis

- Bibliographic references