- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Indonesia has experienced a quick succession of new governments and fundamental reforms since the collapse of Suharto's dictatorial regime in 1998. Established patterns in the distribution of wealth, power and knowledge have been disrupted, altered and re-asserted. The contributors to this volume have taken the unique opportunity this upheaval presents to uncover social tensions and fault lines in this society. Focusing in particular on disadvantaged sectors of Balinese society, the contributors describe how the effects of a national economic and political crisis combined with a variety of social aspirations at a grass roots level to elicit shifts in local and regional configurations of power and knowledge. This is the first time that many of them have been able to disseminate their controversial research findings without endangering their informants since the demise of the New Order regime.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inequality, Crisis and Social Change in Indonesia by Thomas Reuter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Thomas A. Reuter

Indonesia has been in a state of continuous economic and political crisis since the fall of former President Suharto's authoritarian government in 1998. The crisis persists as the current government of President Megawati Sukarnoputri struggles to rebuild a country torn apart by decades of corruption, nepotism and state oppression, as well as by interethnic violence, religious conflict and separatism.1 Under the seemingly chaotic conditions of the last 4 years, social tensions and conflicts have surfaced that, for decades, had been simmering under a lid of political repression and remained hidden behind the veil of a culture of enforced silence.

While it may have been viewed and widely reported upon as a cause of concern for Indonesia and its neighbours, this continuing state of instability also provides an opportunity. People who had been silenced during the so-called ‘New Order’ (Orde Baru) period of Suharto's rule have become relatively free to voice their grievances and pursue their interests under the momentarily more equitable political conditions created by the social turmoil and major political restructuring since 1998. Indeed, some of the silences that are being broken in the current ‘Reform Period’ or Era Reformasi reach back much further still. Some contemporary struggles relate to patterns of inequity established in the course of Bali's pre-colonial or colonial history. A difficult time though it may be, the present period of uncertainty thus holds a potential for Indonesians and engaged Indonesianists to witness political and social change unfolding at a rather dramatic pace.

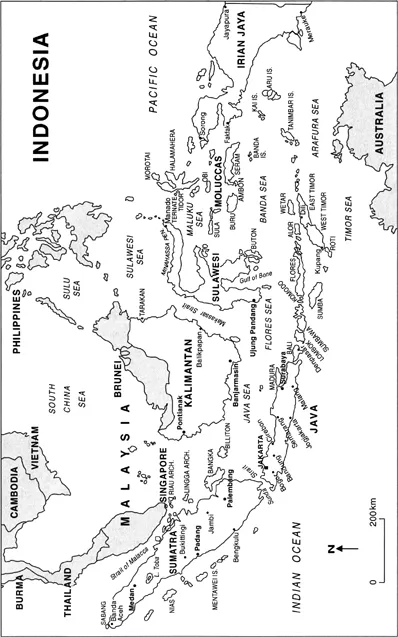

This volume presents case studies of social inequality, conflict and change on the island of Bali with the aim of illuminating some of the complex interactions between the local, regional, and national aspects of the current crisis in Indonesia (see Map 1.1). It incorporates contributions from eminent scholars in a range of disciplines, as well as presenting the innovative work of some younger researchers to a wider audience for the first time. The chapters in this collection were initially presented at The Third Australian Balinese Studies Conference, held on 24–26 September 1999 at the University of Melbourne and organized by the editor. The aim of this gathering had been to assess and discuss the dramatic changes in the

Map 1.1 Indonesia.

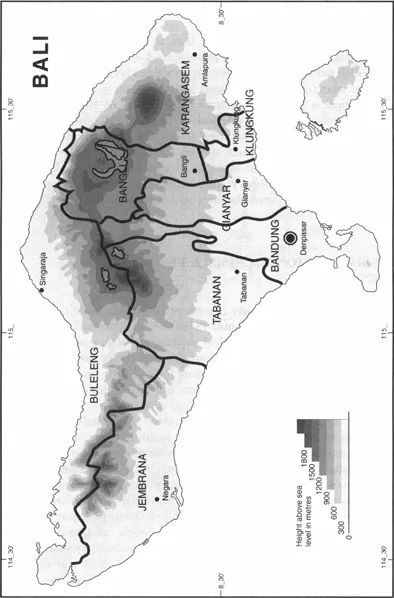

sociopolitical landscape of Bali emerging in the aftermath of the Asian economic crisis and following the collapse of former President Suharto's authoritarian government in Indonesia. Several revisions have been necessary to keep the contributions in pace with changing local conditions in Bali, and with the rapid unfolding of political events on a national level (see Map 1.2).

The contributors further examine how a ‘global’ economic and a ‘national’ political crisis are being experienced at a grass-roots level in Indonesia, with particular emphasis on interactions between local, regional and national structures of power and knowledge in a Balinese setting. Special attention is paid to disadvantaged sectors of Balinese society, including marginal ethnic or religious groups, rural populations and women, and to their efforts to renegotiate their social position during this moment of crisis. With their special focus on ‘muted worlds’ and social change, the authors are aspiring to add a new dimension to the study of Balinese culture, history, and society from a contemporary and critical perspective.2 All contributions are based on original research findings.

INDONESIA'S NATIONAL CRISIS: A TWOFOLD CHALLENGE

A mood of profound uncertainty has swept Indonesia since the collapse of the ‘New Order’ regime of former President Suharto on 21 May 1998. After 32 years of systematic political repression of opposition parties, unions and individual dissidents, the sudden collapse of the regime came as a surprise to many. Subsequent events have shown that Indonesians were not very well prepared to capitalize fully from the opportunity to build a genuinely democratic society and government.

At first an unpopular interim government was established under the leadership of former Vice-President, Jusuf Habibie. Habibie took a number of important steps toward democratization and decentralization, notwithstanding the fact that he had been a prominent figure within Suharto's Golkar Party. During his brief time in office, the people of East Timor were given the opportunity to decide on their own future and promptly voted for independence. This decision precipitated widespread atrocities against Timorese at the hands of pro-integration militias, followed by a UN-sponsored, Australian-led military intervention and the separation of East Timor from Indonesia. After the first free parliamentary election in Indonesia in June 1999 and the rejection of his ‘accountability speech’ by the new parliament on 20 October 1999, Habibie was replaced by Abdurrahman Wahid, until then the leader of the largest and relatively moderate Indonesian Muslim organization, Nahdatul Ulama (NU).

Megawati Sukarnoputri, the popular daughter of Indonesia's first president, Sukarno, had to content herself with becoming Wahid's

Map 1.2 Bali.

vice-president, even though her ‘Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle’ (PDI-P) had won the largest number of seats of any party in the house of representatives (the DPR). Sixteen months later, however, charismatic President Wahid or ‘Gus Dur’, as he is colloquially referred to, came under threat of impeachment on allegations of involvement in the ‘Buloggate’ and ‘Bruneigate’ corruption scandals and on accusations of erratic and ineffective government. On 1 February 2001, a motion of censure was issued by the DPR and, when Wahid failed to respond to the members’ satisfaction, a second censure motion was issued on 30 April 2001. After a failed attempt to dissolve the National Assembly (MPR) and impose a state of emergency, Gus Dur was finally forced to step down on 23 July 2001, to be replaced by Megawati Sukarnoputri.

One year later, Megawati's government is again threatened by rising popular discontent in response to her failure to address Indonesia's growing economic woes, stamp out government corruption, and resolve widespread and violent inter-ethnic, interreligious and secessionist conflicts. Another major issue is the failure to establish supremacy of the law, which has encouraged the rise of militant organizations and the spread of ‘organized crime’ (premanisme), as well as increasing the incidence of vigilante killings of petty criminal offenders. In short, many Indonesians hold the current state, and particularly its security apparatus and legal system, to be dangerously ‘weak’ (especially in comparison to the Suharto state). Others, including the army and militant religious or political movements, take this weakness as an invitation to expand their influence and power. The popular sentiments working in the favour of militant movements stem from, among other issues, Indonesia's growing dependency on the IMF and other creditors and from wide-spread Muslim opposition to the US war on Afghanistan.

During this prolonged period of national economic and political crisis, local and regional patterns in the distribution of wealth, power and symbolic capital, which had become entrenched during the 32-year reign of Suharto, have had to be re-examined, modified, or reasserted, in Bali and similarly in other Indonesian provinces. In some places these negotiations have been accompanied by severe violence. In Bali and elsewhere, similar processes of change have unfolded under less dramatic circumstances and so have remained largely invisible to outsiders. Likewise, while some of the changes that have occurred relate to the country's formal political system and are thus readily observable (such as the new regional autonomy legislation that affords greater independence to Bali and other provinces), other transformations relate to more informal patterns of material and symbolic capital distribution and are less visible to the outside world.

In analyzing some of these obvious and less obvious changes, researchers involved in Balinese and Indonesian Studies have had to contend with two important questions that are of general sociological interest: What impact does a global or national crisis have on regional societies or local communities? And, how do such destabilizing external influences link up with pre-existing inequalities and tensions within these narrower contexts of social interaction?

One challenge lies in trying to tackle the general sociological issue of ‘social change’ from the angle of a concept of ‘crisis’. In contemporary social science, few would debate that social change occurs continuously. It is anything but certain, however, how and under what historical circumstances social change may increase its velocity, or whether a major crisis may even transform a society completely. In order to address these questions in relation to an analysis of the current Indonesian crisis, the contributors emphasize that it is impossible to identify the form and degree of change taking place in Indonesia today without a proper understanding of the legacy of the New Order period, in all its local and regional complexities.3

A second challenge concerns the issue of the ethics of social science. If certain social groups who have been silenced in a given society, then we may have a responsibility to acknowledge and support their concerns. The voices of such disadvantaged people may become momentarily amplified during periods of great social instability and change, but this does not guarantee an improvement in their condition. The least we can do as social scientists is to lend some support by bringing the concerns of disadvantaged sectors of the societies we study to the attention of a broader audience.

In this context, it is necessary to acknowledge that many Western researchers were to some extent gagged by the New Order government as well, except for those who were willing to face a ban on continuing their work or imperil local informants with whom they could be connected. The present volume aims to take at least some steps—partially retrospective and partially proactive—toward exposing some of the inequalities and forms of oppression that characterized life in Bali under the rule of Suharto and his many local cronies and that still cast their shadow over the hopes of the current Era Reformasi.

It is a starting hypothesis of this book that long-standing social divisions, inequalities and associated tensions in a society, as well as the strength of its culture-specific mechanisms for peaceful negotiation, become accentuated and more visible at a time of major economic or political upheaval. The advent of such a crisis and of a period of dramatic social changes, however, presupposes an earlier historical period in which a normal process of continuous change was either stifled (by various means of oppression or silencing) or not fully acknowledged and accommodated in public discourses. Rather than promoting sensationalism or opportunism, the Indonesian crisis, is herein treated as a contemporary phenomenon with its roots in a history of three decades of oppression. Nevertheless, the new spirit of openness in the Indonesia of Reformasi provides unique opportunities for morally engaged social scientists to develop a more complete understanding of the local societies they have been studying, sometimes for decades already, without fully recognizing all of the hidden tensions and dormant potential for conflict within them.

It is proposed that latent social tensions can surface at critical historical moments in two fundamental and intimately connected forms; as practical rivalries over the redistribution of material wealth and power or as competing discursive claims raised in the context of a shifting symbolic economy of knowledge. Current social changes in Bali and elsewhere in Indonesia thus need to be examined from both a material and a symbolic perspective, and the contributors have endeavoured to do so. In terms of practical research, this requires exploration of the economic, political, and representational strategies employed by people from different sectors of Balinese society in the pursuit of a diversity of material and symbolic interests, as they seek to capitalize or protect themselves from the effects of the current turmoil.

HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Periods of dramatic social change are not unprecedented in the history of Bali's interlaced economies of power and knowledge. The island's society has been subject to several major transformations in the wake of colonization, Indonesian independence, population growth, modernization, and through active engagement with a globalizing world market and international tourist industry. In each case new conflicts arose and the discourse of conflict differed, as did some of the players and the stakes. But there are also some interesting parallels to, and resonance with, earlier crises, both at a national and a regional level.

Bali, for example, was one of the provinces worst afflicted by the mass killings in the wake of the violent anti-Communist purge of 1965-1966, which marked the collapse of the Sukarno government and Suharto's rise to power (see Darma Putra, this volume). In the present crisis, however, the idiom of social conflict is no longer one of competing political ideologies so much as an idiom of religious and ethnic difference. At the same time, however, the trauma of the 1965–1966 killings (not only of Communists but also of other ‘undesirables’, as defined by Bali's internal and local politics), which was a taboo topic in the Suharto years, features very prominently in current public debates. In part, this may reflect the fact that some of the underlying economic inequalities and related class issues in Balinese society, which had surfaced at that time, were never resolved and are resurfacing today.

The current crisis provides an opportunity for releasing different tensions that have been building in Bali for different amounts of time. Many of the more recent grievances certainly relate to the political silence imposed by former President Suharto's oppressive regime (see MacRae, this volume). However, other silences have been observed for so long—dating back to the pre-colonial and colonial periods of Balinese history—or are so fundamental —such as gender-related issues (see Kellar, and Nakatani, this volume)— that they have become almost intrinsic to Balinese society and culture and appear rather difficult to break. In any case, these grievances, new and old, have come to the surface to meet new opportunities for public expression and possible resolution.

Recent political events have precipitated a dramatic weakening of Indonesia's political and administrative establishment, with the instalment of new and fragile governments under presidents Habibie, Wahid, and Megawati in the place of the Suharto dictatorship. Amidst on-going complaints about widespread government corruption and nepotism, many previous alliances of high mutual profitability, within and between economic, political and cultural elites, have become untenable or at least unstable. Some past offenders have had to scramble for cover or reinvent themselves, and a few, including Bali's former governor, Ida Bagus Oka, have ended up in jail. The resulting uncertainty has encouraged people who have been economically disadvantaged, excluded from political participation, or culturally marginalized to call for social changes in their favour. In several of the following chapters, Bali's rising social tensions are examined from the perspective of such marginal groups or locations.

LOCAL ANATOMY OF A NATIONAL CRISIS

In Balinese society, open and physical confrontations between individuals tend to be avoided or concealed. When they do occur, and when the fact cannot be denied, social disapproval is usually extended to all of the parties involved, given that violent behaviour is classed as ‘unrefined’ (kasar), animal-like and, hence, dehumanizing. Studied social avoidance or ‘maintaining silence’ (puik) traditionally has been a much more common and legitimate alternative for showing opposition. A deep and widespread concern for sheltering the island's all-important tourist industry from the negative effects of violent political turmoil acts as a second and, perhaps, even more significant constraint. This does not mean that the idea of h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Being modern in Bali after Suharto

- 3 Art and peace in the safest place in the world: a culture of apoliticism in Bali

- 4 Reflections on literature and politics in Bali: the development of Lekra, 1950–1966

- 5 Transformations of a genre of Balinese dance drama: Arja Muani as the modern-day agent of classical Arja's liberal gender agenda

- 6 Ritual as ‘work’: the invisibility of women's socio-economic and religious roles in a changing Balinese society

- 7 The value of land in Bali: land tenure, landreform and commodification

- 8 Mythical centres and modern margins: a short history of encounters, crises, marginality, and social change in highland Bali

- 9 Unity in uniformity: tendencies toward militarism in Balinese ritual life

- 10 Indonesia in transition: concluding reflections on engaged research and the critique of local knowledge

- Index