eBook - ePub

Innovation in Construction

An International Review of Public Policies

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How can innovation in the construction industry be strengthened? What instruments and approaches are being used by governments to promote it? What works and under what circumstances? These key questions have profound implications. This book presents a framework for the analysis of innovation models and systems in construction and an international comparison of these systems, with a focus on their application in practical policy development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Innovation in Construction by Andre Manseau,George Seaden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

André Manseau and George Seaden

1.1

PUBLIC POLICY CONCERNS WITH THE CONSTRUCTION SECTOR

The very size and pervasiveness of the construction industry cause most governments to show interest in its well-being.

Together with the related sectors (manufacturers of building products and systems, designers and facility operators) it is one of the major economic activities in every nation, accounting for about 15% of national GDP. It also has a significant impact on living standards and on the capability of the society to produce other goods and services or to trade effectively. As a well-established sector, construction has been strongly determined by local tradition and culture, and geographical factors such as availability of material and climate. Construction provides houses to live in, buildings to work in and infrastructure that supports communication and transportation of the modern society.

Official statistics generally limit the construction sector to the value-added activity of firms that construct buildings and infrastructure as well as to those who install construction sub-systems (electrical works, plumbing, air systems, structure, finishing, etc.). Figure 1.1 shows that construction’s (as previously defined) share of national GDP has slowly decreased during the last two decades to reach about 4–6% for almost all countries, except Japan with a 10%.

Major changes are occurring in the construction industry. Demand is shifting towards more functional buildings (with greater concern for user satisfaction and productivity), more sophisticated equipment such as intelligent devices for better control of energy efficiency or indoor environment, improved working/living conditions, and more respect for environmental constraints. National quality standards and building costs are increasingly facing international comparisons. Some of the major players in engineering services, manufacturing building products or equipment, and operation of large facilities are becoming international in scope.

Following a period of post-war expansion, the demand for construction has decreased in the last decades. However, the demand for machinery and equipment linked to production processes, not incorporated in the structure, continues to increase. Residential construction also slowed down as demographic pressure diminished. This may be an indication of a fundamental change that is taking place in the structure of the construction industry of many industrially developed countries (Bon, 1994). Cyclical nature of the demand tends to make such long-term predictions difficult. However, in general, spending on operating, maintaining, renovating and reusing existing facilities is growing as the percentage of the total output. These latter activities are not well captured by official statistics limited to constructors and assemblers. Some (Carassus, 1999) suggest that the industry is now more in the business of optimisation of the use of the existing stock rather than in the provision of new facilities.

Figure 1.1: Construction industry as a percentage of GDP

Source: OECD Statistics, International Sectoral Database (ISDB), 1999

Governments own and operate an important share of the built environment in every nation. Governments of the OECD group own between 10% to 25% of their total country fixed assets in a form of public works, which include buildings and general purpose infrastructure (OECD, 1997). These facilities require on-going maintenance and renovation as well as new additions, all at a significant cost, to satisfy demands for high-quality public services.

By various measures (Keys and Caskie, 1975; Seaden, 1997; Industry Canada, 1998) such as: total factor or labour productivity, customer satisfaction (Barrett, 1998), R&D intensity (Revay and Associates Ltd., 1993 and 1999) or (Barrett, 1998), R&D intensity (Revay and Associates Ltd., 1993 and 1999) or worker’s skill levels, these industries in the OECD and other countries, has lagged behind most sectors of the economy.

Over the years this has been a subject of various reports, which have advocated a more rationalised regulatory system, reduction in the adversarial regime between various participants, better risk-sharing, greater investment in R&D or improved training of labour and management. There has been gradual progress in some of these areas but no country has yet undertaken systematic changes to the overall delivery system.

1.2

DEFINING THE CONSTRUCTION SPACE

The economic space of construction is much larger than that defined by traditional “construction” statistics, limited to value-added site activities of general contractors and speciality trades (roofers, plumbers, structural assemblers, excavators, landscapers, etc.). There is a general agreement that it includes the design of buildings and infrastructure (engineering and architectural services), the manufacture of buildings products and of machinery and equipment for construction, and operation and maintenance of facilities. However, statistical data for these construction-related activities are seldom directly available, as they are usually included in other manufacturing or service industry surveys. Rough estimates of the overall importance of the industry, which have recently become available, show that it is much larger than previously perceived.

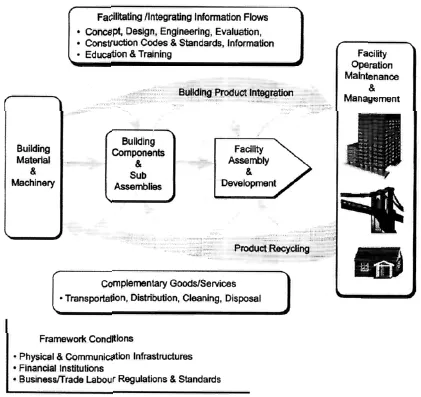

The study of innovation in the construction sector raises many challenges. The sector is a very complex arena, involving numerous agents and interactions in developing and adapting innovations. Figure 1.2 presents a systematic approach to the key actors involved in construction who can undertake innovation activities.

These actors include:

- building materials suppliers who provide the basic materials for construction such as lumber, cement and bricks

- machinery manufacturers who provide the heavy equipment used in construction such as cranes, graders and bulldozers

- building product component manufacturers who provide the subsystems (complex products) such as air quality systems, elevators, heating systems, windows and cladding

- sub-assemblers (trade speciality and installers) who bring together components and material to create such sub-systems

- developers and facility assemblers (or general contractors) who initiate new projects and co-ordinate the overall assembly

- facility/building operators and management who manage property services and maintenance

- facilitators and providers of knowledge/information such as scientists, architects, designers, engineers, evaluators, information services, professional associations, education and training providers.

- providers of complementary goods and services such as transportation, distribution, cleaning, demolition and disposal

- institutional environment actors who provide the general framework conditions of the business environment such as the physical and communication infrastructure, financial institutions and business/trade general labour regulations and standards.

Figure 1.2: Key agents, major types of interactions and framework conditions in the construction sector (source: Manseau, 1998)

The above list provides a basic typology of construction related activities; some of those actors may be suppliers or clients of others in the production process and specific firms can be involved simultaneously in several of above activities. Some larger firms offer vertically integrated range of services from design, through manufacturing of some products or components, to building and operation of facilities.

The ultimate client, the owner of the constructed facility, can influence the innovative behaviour of various actors by identifying specific novel requirements to be supplied by the developers, building product suppliers, contractors or operators or through the general expectation of high-quality and viability, over the useful life of the project.

Construction activity has several distinct characteristics, which makes it unlike any other industrial sectors (ARA Consulting Group, 1997; Carassus, 1998 and 1999; Toole, 1998).

The site-based nature of construction activities causes the uniqueness of each construction project. It is always located on a distinct site, subject to local environmental and climatic conditions, most likely built by a different work-crew. Even two standard subdivision homes of identical design are likely to be somewhat different.

Every new or renovation/repair project is also truly a prototype. While some degree of uniformity has been tolerated in the past, with the increase in the wealth of Western industrial countries there has been an ever-growing trend in demanding custom solutions to satisfy real or perceived individual requirements. Some sources suggest (Flanagan et al., 1998) that this drive to customization as well as demands for higher quality can be achieved through the introduction of IT-supported production methods, currently used in manufacturing.

Local demands for constructed product are of extreme diversity. Industry responds to the occasional local/regional need for large hospitals, major airports, tunnels, and water treatment plants as well as to the more constant demand for single-family homes, office buildings or street improvements.

Constructed facilities tend to be very durable, lasting 25-50 years and longer. When obsolete, they are most often repaired, modernized and sometimes radically transformed to suit new requirements rather than disposed of and replaced with new, more typical for manufactured products. This also impacts on construction demand, which stresses conservative, traditional solutions and emphasises reliability. Generally however, issues of life-cycle cost or sustainability are seldom addressed, focus remaining on the initial cost of acquisition.

Aesthetic, safety, site and environmental design considerations are set not only by the builder or the owner but also by the community at large. Regulation and standards are more rigorous in construction than in most other sectors of economy, with the involvement of several levels of governments (local, provincial, national).

Construction is highly fragmented and firms, mostly small in size, tend to respond to local market needs and to control only one of the elements of the

Construction is highly fragmented and firms, mostly small in size, tend to respond to local market needs and to control only one of the elements of the overall building process. Some firms have been trying to achieve greater control of their production together with greater innovation capability through increased integration and alternate delivery systems such as design-build or build-owntransfer (BOT).

Over a number of years there has been an international trend to “industrialise” construction through greater pre-fabrication, modularization, standardisation and other manufacturing-type production techniques. There is an almost implicit wish that if construction was like manufacturing, many of its quality and productivity problems would disappear and innovation would flourish.

While many of these initiatives have shown positive results, construction, because of the variable site requirements, the durability of the product and the impact on the surrounding community, remains unique and significantly different in its characteristics from other industrial sectors.

CHAPTER 2

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

André Manseau and George Seaden

There has been an increase in the general understanding of industrial innovation systems and processes (OECD, 1996 and 1997b; Hobday, 1998), with some new, interesting evidence specific to the construction industry (Bernstein and Lemer, 1996; CRISP, 1997; Winch and Campagnac, 1995). In particular, the role in innovation of the government through its various public policies and programmes has been identified. It is this general knowledge of innovation, adapted to the characteristics of the construction industry, which constitutes the analytical framework of this paper.

2.1

DEFINING INNOVATION

With the increasing openness of the world trade and globalisation there has been ever-growing interest in what makes firms truly competitive. Opinions on that matter have greatly evolved in the past twenty years and continue to be open to debate. Porter (1998) and others suggest that during the last twenty years Western companies have been responding to the international competition through continuous improvement in their operational effectiveness. At present time, Western companies can seldom use low cost of labour or of raw materials as theirs competitive advantage. Thus, re-engineering, lean production, investments in the information technology, TQM and other techniques of optimising productivity and asset utilisation have now all become parts of companies’ efforts to remain/become competitive in the global market-place. Porter also suggests that continuous improvement in best practice utilisation must now be considered a pre-condition to achieve profitability and that companies have to create unique competitive positions through integration of all their competencies. To have truly lasting competitive advantage they need to offer differentiated, value creating new products to their customers.

These competitive needs as well as spectacular achievements of the hightechnology sectors of the economy have driven our interest in the generation of new ideas and its implementation i.e. what is now being considered innovation. There is no generally accepted definition of innovation at the present time, however there has been noticeable convergence as to its principal characteristics.

This point can be illustrated by sample of general definitions:

- “The process of bringing new goods and services to market, or the result of that process” (Advisory Council on Science and Technology, 1999).

- “A technological product innovation is the implementation/commercialisation of a product with improved performance characteristics such as to deliver objectively new or improved services to the customer. A technological process innovation is the implementation/adoption of new or significantly improved production or delivery methods. It may involve changes in equipment, human resources, working methods or a combination of these” (OECD, 1997a).

Construction industry sources also show a variety of definitions:

- “Application of technology that is new to an organisation and that significantly improves the design and construction of a living space by decreasing installed cost, increasing installed performance, and/or improving the business process” (Toole, 1998)

- “the successful exploitation of new ideas, where ideas are new to a particular enterprise, and are more that just technology related—new ideas can relate to process, market or management” (Construction Research and Innovation Strategy Panel (CRISP), 1997)

- “apply innovative design, methods or materials to improve productivity” (Civil Engineering Research Foundation (CERF), 1993)

- “anything new that is actually used” (Slaughter, 1993)

- “first use of a technology within a construction firm” (Tatum, 1987).

These definitions may display specific biases of different sources, studies and organisations. Nevertheless certain trends and convergence can be observed. Increasingly, innovation appears to be viewed as a process that enhances the competitive position of a firm through the implementation of a large spectrum of new ideas. A recent business-level survey by A.D.Little of factors that allow a firm to be innovative, involving significant sample of companies in 8 OECD countries, disclosed a much more comprehensive and complex image of the innovation process. What distinguishes the “leaders” from the “pack” is their ability to combine marketing, internal organisation and technology. “Innovative products don’t necessarily build business, often non-innovative products build business, what builds business is innovative companies” (Brown, 1998). Yet domestic and international competitive pressures are increasing in all sectors of the economy to deliver ever-greater value to the customer, mostly through innovation.

Because every construction project, new or repair, can be considered a prototype, at a new and different site and most often with a different owner, there is significant opportunity and tendency to do something new and/or distinct every time. Building practitioners and their clients have often interpreted this as innovative behaviour. But is the industry truly innovative, i.e. good at adopting new processes and products?

Unfortunately, official statistics are limited in measuring innovation. Most common indicators for assessing innovation are related to research and development (R&D) activities: R&D expenditures, number of R&D personnel, number of patents, number of publications and their citations. As many authors and OECD reports have stressed (OECD, 1996; OECD, 1997a), innovation can emerge from various sources of activities, and not only from R&D, although it constitutes an important part of innovation activities.

As discussed further in this volume, models linking R&D and innovation are complex and generally display non-linear relationship. Nevertheless, level of R&D activity has been positively correlated with the relative innovativeness of various industrial sectors, particularly high tech manufacturing sectors, and is considered a valid indicator.

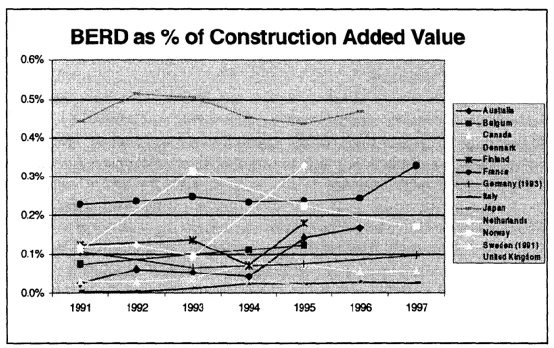

Expenditures on R&D in construction (statistically limited to contractors and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Analytical Framework

- Chapter 3: International Practice in Construction Innovation Systems

- Chapter 4: Innovation Policy and the Construction Sector in Argentina

- Chapter 5: Construction Innovation and Public Policy in Australia

- Chapter 6: Public Policy Instruments to Encourage Construction Innovation: Overview of the Brazilian Case

- Chapter 7: Canadian Public Policy Instruments that Affect Innovation in Construction

- Chapter 8: Innovation in the Chilean Construction Industry: Public Policy Instruments

- Chapter 9: Innovation in the Danish Construction Sector: The Role of Public Policy Instruments

- Chapter 10: Innovation in the Finnish Construction and Real Estate Industry—The Role of Public Policy Instruments

- Chapter 11: Innovation in the French Construction Industry: The Role of Public Policy Instruments

- Chapter 12: Innovation and Innovation Policy in the German Construction Sector

- Chapter 13: Japan Public Policy Instruments and Innovation in Construction

- Chapter 14: R&D in Construction: The Portuguese Situation

- Chapter 15: Innovation Policy and the Construction Sector in the Netherlands: Brokering and Procurement to Promote Innovative Clusters

- Chapter 16: South African Public Policy Instruments Affecting Innovation in Construction

- Chapter 17: Innovation in the British Construction Industry: The Role of Public Policy Instruments

- Chapter 18: The U.S. Federal Policy in Support of Innovation in the Design and Construction Industry

- Chapter 19: Public Policy Context and Trends

- Chapter 20: Conclusion

- Bibliography