eBook - ePub

Societies and Nature in the Sahel

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Societies and Nature in the Sahel

About this book

This book explores the links between environment and social systems in the Sahel, integrating ecological, demographic, economic, technical, social and cultural factors. Examining the conditions for land occupation and natural resource use, it offers a conceptual and practical approach to social organization and environmental management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Societies and Nature in the Sahel by Philippe Lavigne Delville,Emmanuel Gregoire,Pierre Janin,Jean Koechlin,Claude Raynaut in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS AND DEGRADATION FACTORS IN THE SAHEL

Jean Koechlin

The Sahelian area is primarily identified by a set of physical and natural features. The principal criteria for a delineation and description of its characteristics are drawn from the observation of climate, soils and vegetation. The combination of these different variables creates a wide heterogeneity within local sites. The unequal impact of human activity brings with it an additional element of diversification, creating transformation processes which, in their most extreme manifestations, can lead to the degradation of environments which is then difficult to reverse.

It is the different factors associated with the variability in local situations that will be examined in this chapter.

CLIMATIC CONDITIONS

In the zone under consideration, the availability of water (more precisely the possibility of exploiting rainwater) represents the fundamental limiting factor for primary production. In this zone, therefore, primary production is dependent upon the seasonal distribution of precipitation and its annual variation even more than the annual, global amount of rainwater. The climate of the Sahel is determined by two alternating aerial fluxes.

The first is a flux of dry air, flowing north-east to east, which results from the Saharan high pressures of the Azores anticyclone. This dry air is known as the Harmattan. It is often dust-laden and blows from December to March. The second is a flux of humid air, flowing south-west to west, which results from the oceanic high pressures of the Saint Helen anticyclone. A zone of separation between these two fluxes, known as the Intertropical Front (ITF), oscillates during the year between the Gulf of Guinea in January and the 25°N parallel in August. This oscillation determines the rhythm of the humid and dry seasons.

The rains generally begin in the south in April and progress towards the north, arriving in June. The maximum rainfall is almost always reached in August. The rainy season ends at the beginning of September in the north, and in October further south. The downpours are often heavy and short at the beginning of the season, which can bring a considerable increase in run-off and erosion of soils which have dried out and are, therefore, difficult to infiltrate. In August the rains are less intense, allowing the soil (already moist) to absorb the rainwater better. It is, therefore, possible to observe a pronounced gradient of average rainfall from north to south, across the whole of the Sahel. There also exists, although less pronounced, a gradient of aridity in the shape of a crescent, from west to east, which results in a slight incline in isohyets. The shift southward of the 500 mm isohyet between Senegal and Chad is in the 200 km range. In reality, however, the situation is susceptible to considerable change from year to year.

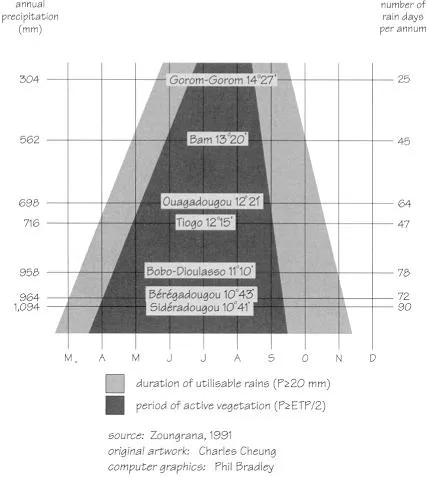

Figure 1.1 The relationship between latitude, rainfall and rainy season characteristics in Burkina Faso (1979–88)

In addition to the classic meteorological data, an ecologically important feature is the length of time available for active vegetation growth, defined as the period during which the rains are equal to or greater than half of the potential evapotranspiration. This will directly determine the vegetal productivity and the possibility of plant cultivation of shorter or longer cycles. This period decreases from south to north. In Burkina Faso, for example, the period of active vegetation is in the region of five months in Ouagadougou (12° 21' N) for 698 mm of annual rainfall, but only lasts two and a half months in Gorom-Gorom (14° 27' N) for 304 mm of annual rainfall (Figure 1.1).

According to these various elements, in this area a bioclimatic zoning is usually established, composed of different sectors which can also be identified by their vegetation:

- Sub-desert sector: annual rainfall less than 200–250 mm and a dry season of ten or more months.

- Sahelian sector: annual rainfall from 200–250 mm to 550 mm, dry season of eight to ten months, steppe vegetation.

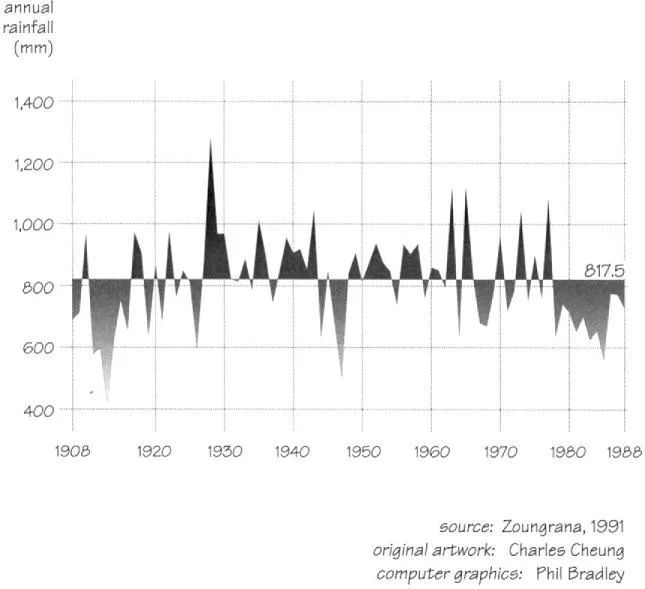

Figure 1.2 Long-term rainfall variability in the Ouagadougou region (1908–88)

- Sub-Sahelian sector: annual rainfall from 550 to 750 mm, dry season of seven to eight months, transitional steppe to savanna vegetation.

- North Sudanese sector: annual rainfall between 750 and 1,000 mm, dry season of six to seven months, typical Sudanese savanna vegetation.

The variation in precipitation is a normal component of arid zone climates, and of the Sahelian climate in particular. The droughts which the entire Sahel has experienced in recent decades, while perhaps exceptional in their duration, fit perfectly in this context. Figure 1.2 clearly shows this characteristic with, since the beginning of the century, alternating years and varying periods of dry and humid years.

The droughts of 1910 to 1916 and 1941 to 1945 are comparable in their intensity, if not their duration, to those that are now being experienced. Yet the 1950 to 1965 period is characterised by an extremely large number of years with surplus rainfall. Since about 1965, however, the rainfall deficits have been almost chronic in the countries of the Sahel and have had a tendency towards being more pronounced, with absolute minimums being recorded at many stations in 1983–4. The example of Burkina Faso (Figure 1.3) is absolutely typical in this regard, showing a regular tendency towards diminishing precipitation since the 1960s.

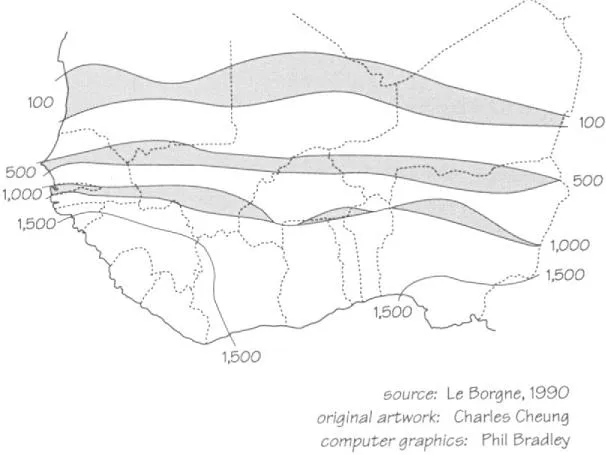

The rainfall deficits calculated for the period 1961 to 1985 for the Sahel (in comparison to the normal years of 1931 to 1960) are in the order of 25 to 30 per cent in the northern regions and from 20 to 25 per cent further south. During the same period, the isohyets have shifted towards the south, a shift that is as strong as the precipitation is weak, i.e., 200 to 300 km for isohyet 100 and 100 to 150 km for isohyet 500 (Figure 1.4).

Unfortunately, the short duration of these observations does not allow us to detect a periodicity in this phenomenon. It is difficult to know whether the low rainfall recorded since the end of the 1960s reflect an irreversible modification of the climate or a simple temporary accident.

A general tendency towards drought is perceivable since the beginning of the century as indicated below by the data for St Louis (Le Borgne, 1990):

| Years | Average annual rainfall |

| 1901-30 | 409.6 mm |

| 1931-60 | 341.7 mm |

| 1961-85 | 262.9 mm |

This poses a problem regarding the choice of a standard (normal or deficient) precipitation situation for the period under study. Beginning in 1991, the member countries of the World Meteorological Office adopted 1961–90 as the standard, instead of 1931–60. Therefore, what could have been considered a deficit must now be considered normal. This, of course,does not change the actual rainfall received, but its implications will affect everything concerned with the problems of agropastoral development, because when the 1931–60 averages are used they give a much too optimistic view of the situation.

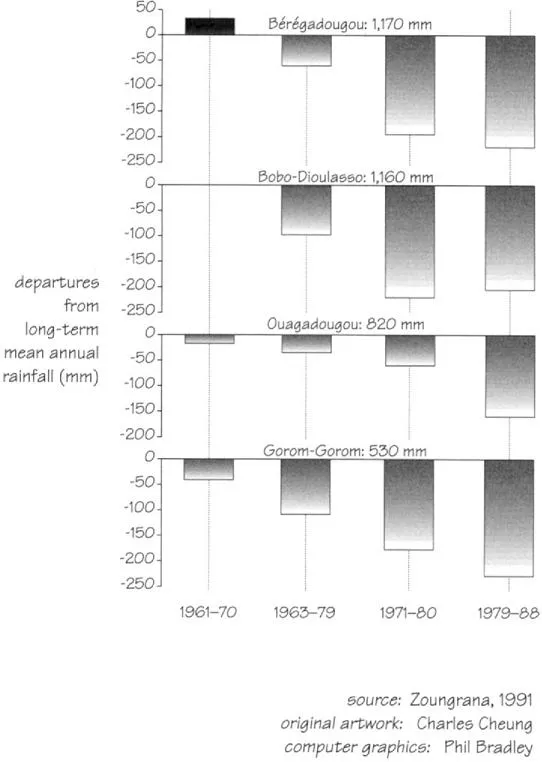

Figure 1.3 Rainfall variability at four locations in Burkina Faso

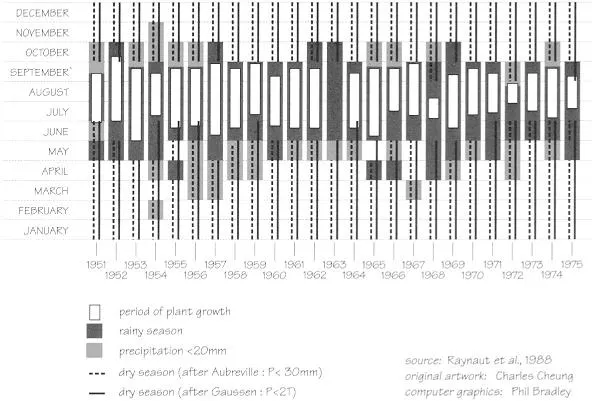

The repercussions of this aridification phenomenon are considerable in many areas. Nevertheless, within this tendency, the considerable variation of the rains in time and space must again be emphasised. The ecological significance of this variation is not easy to visualise since it is related not only to the importance of the rains but also to the length of the seasons, to the date of their onset, to the number of days of rain and to the frequency of humid and dry periods during the course of the rainy season. Figure 1.5 illustrates some of these points, and clearly shows the wide range of inter-annual variation for these parameters.

Figure 1.4 The southward displacement of the 100, 500 and 1,000 mm isohyets in the western Sahel during the period 1961–85

The concept of aridity is complex and has to do with a number of factors. Besides their precipitation regime, the Sahelian countries are characterised by high temperatures, with absolute maximums reaching more than 45°C, with low atmospheric humidity for most of the year. Potential evaporation values are high and the water balance (actual evapotranspiration (AET)/ potential evapotranspiration (PET)) is less than one for much, if not all, of the year. For example, in Mopti, precipitation (P) equals 552 mm, while potential evapotranspiration is 1,984 mm, with a positive balance for only one month. In Gao the situation is even more severe, with precipitation at 261 mm and potential evapotranspiration as high as 2,255 mm and no months with a positive balance.

This emphasises the fact that groundwater reserves barely come into the picture and that the water imbalance (AET/PET), the principal factor of vegetation productivity, is almost equivalent to the rainfall deficit (P/PET).

Figure 1.5 Inter-annual variability of rainfall characteristics at Maradi, Niger (1951–75)

EDAPHIC CONDITIONS

In the context of such aridity, how soils perform in relation to water (depth, texture, structure) is fundamental, especially as precipitation is low and uncertain. As a consequence agriculturalists may give soil moisture performance more significance than soil fertility.

Within the framework of traditional techniques, sandy soils make better use of precipitation because of their permeability, their capacity to retain moisture to a sufficient depth, the availability of this water to deep-rooted plants and low evaporation. Compact soils are much less favourable because of their low permeability which leads to run-off. The soil’s compactness makes root penetration difficult. More importantly, water retention occurs at a shallow depth and, although the water is strongly retained in the soil, it is inefficiently used by roots, yet easily evaporated. These compact soils are also much more difficult to work, which is hardly compatible with the land use strategies on which peasants’ technical systems are often based, as will be seen later in Chapter 5. Deep ploughing, with the aid of draft animal or mechanised cultivation, allows these constraints to be overcome to a certain extent, and puts more fertile clay soils, traditionally abandoned to pasture, within reach of agriculturalists.

Contrary to what is observed in tropical humid zones, where the deep alteration of rocks leads to very deep and relatively uniform soils, arid climates are responsible for a much greater pedological diversity, generally with shallow soils and where the influence of the bedrock remains very pronounced. In addition, the legacy of the recent climatic fluctuations of the Quaternary period translates into large areas of wind-polished hardpan and gravely soils and in the expansion of ancient dunal massif formations.

A certain number of soil types cover a vast geographic expanse:

- Dune soils, with a good moisture capacity, are chemically impoverished. Although sensitive to aeolian erosion, they suffer little from water erosion. Cultivation leads quickly to a structural modification of the surface layers of soil and a drop in fertility. These dunal formations are most widespread in Senegal, Niger and all of the southern Saharan margin.

- Soils over granite bedrock or metamorphic platforms and over sandstone are richer in fine particles and are of variable thickness. Their potential development is essentially based on their physical capacity, their saturation during the rainy season and their compactability during the dry season. Such soils cover only limited areas, and their value is often reduced by the presence of hardpan or graveley elements.

- Soils on hardpan, which are often rich in gravel, are usually very thin, with a minimal moisture reserve, which limits their suitability for agricultural use and makes them more appropriate for livestock production. Such soils cover considerable areas (Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, west of the Niger).

- Other types of soils offer great potential, particularly alluvial and vertisol soils, but cover only small areas.

With certain exceptions (tropical black clays and particular alluvial soils), all these soils have very low chemical fertility (Boulet, 1964), especially the sandy soils because the lack of fine particles reduces the exchange capacity and leads to low base levels. As a result, restoration practices appear to be necessary, such as animal manure, mineral fertiliser (especially to fight certain deficiencies in N, P or K) or fallowing. Where restoration practices in heavily cultivated areas are lacking, the fertility of the land shows pronounced reductions.

The maintenance of fertility is the result of a complex process involving interactions between both mineral and organic soil composition and cultivation practices. In addition, the fertilisation systems must be perfectly adapted to local conditions in order to achieve their full effectiveness. Thus the fallow period will only have a positive effect on the crop yield if a large quantity of biomass is produced, that is on soils which are still relatively fertile. Furthermore, rotation systems of different crops on the same tract of land enable the potential fertility to be most effectively realised. As for inorganic fertilisation, it leads to an increased yield and a reduction in inter-annual variations which are tied to climatic uncertainties. Contrary to what is sometimes thought, inorganic fertilisation does not accelerate the loss of organic matter. Nevertheless, it is evident that combined organic and mineral fertilisation represents the only totally efficacious practice for increasing and stabilising yields and maintaining soil structure (Piéri, 1989).

NATURAL VEGETATION AND ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS

Like agricultural production, natural vegetation is dependent on local conditions and on the perfect integration of the different parameters. The vegetation could, therefore, be considered as an indicator of ecological conditions and of the potential of the locality, and serves as a basis for bioclimatic zoning. For the area under consideration, the scheme already proposed for classifying climate can be used. From north to south, the following formations can be schematically classified (the order is determined essentially by climate):

- Sub-desert sector: Semi-desert vegetation; herbaceous or shrub steppe ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- CONTRIBUTORS

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION: THE ‘‘DESERTIFICATION’’ OF THE SAHEL: A SYMBOL OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS

- 1. ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS AND DEGRADATION FACTORS IN THE SAHEL

- 2. THE DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUE IN THE WESTERN SAHEL: FROM THE GLOBAL TO THE LOCAL SCALE

- 3. POPULATIONS AND LAND: MULTIPLE DYNAMICS AND CONTRASTING REALITIES

- 4. MAJOR SAHELIAN TRADE NETWORKS: PAST AND PRESENT

- 5. A SHARED LAND: COMPLEMENTARY AND COMPETING USES

- 6. SAHELIAN AGRARIAN SYSTEMS: PRINCIPAL RATIONALES

- 7. THE DIVERSITY OF FARMING PRACTICES

- 8. RELATIONS BETWEEN MAN AND HIS ENVIRONMENT: THE MAIN TYPES OF SITUATION IN THE WESTERN SAHEL

- 9. SAHELIAN SOCIAL SYSTEMS: VARIETY AND VARIABILITY

- 10. THE TRANSFORMATION OF SOCIAL RELATIONS AND THE MANAGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES: 1 THE BIRTH OF THE LAND QUESTION

- 11. THE TRANSFORMATION OF SOCIAL RELATIONS AND THE MANAGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES: 2 THE EMANCIPATION OF THE WORKFORCE

- 12. CONCLUSION: RELATIONS BETWEEN SOCIETY AND NATURE–THEIR DYNAMICS, DIVERSITY AND COMPLEXITY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY