1 Hong Kong cinema as part of Chinese national cinema 1913–56

The triangular relationship between China, Britain and Hong Kong that dominated the history of Hong Kong at the end of the twentieth century also operated in the first half of that century, but in a very different way. In the earlier period, the British policy of non-interference in local Chinese affairs and the lack of a defined Hong Kong identity meant that China played a far more dominant role in that triangle than it was to later. As a result, Hong Kong cinema in the early period can be seen essentially, if ambivalently, as part of Chinese national cinema.

The claim that Hong Kong cinema was part of Chinese national cinema in the period of 1913–56 has its foundation in the fact that China was the source and resource for Hong Kong cinema in terms of film market, film talent and financial investment. However, in relation to the concept of national cinema, this argument poses a number of problems. A national cinema is located within national geopolitical boundaries; but Hong Kong cinema was located in a British colony neighbouring China. A national cinema is subject to the laws of the nation-state; but Hong Kong cinema was under British law and colonial regulations. Usually, national films are produced mainly for the domestic market; but successive Chinese national government(s) have often excluded Hong Kong films from the mainland market. Since the early 1950s, mainstream Hong Kong films have not been part of film consumption in China.

These problems in defining Hong Kong cinema as part of Chinese national cinema raise two important questions: In what ways did the Hong Kong film industry function as part of Chinese national cinema? And how did Hong Kong cinema present itself as part of Chinese national cinema?

This chapter advances two major arguments for Hong Kong cinema as part of Chinese national cinema in the first half of the century. First, it argues that the local Chinese community was encouraged to identify with China by the British colonial dual system based on race and on mainland Chinese nationalism. The community’s political and cultural identification with China allowed the mainland Chinese to shape Hong Kong cinema in the interests of China.

Second, as China was the major market for the Hong Kong film industry, it encouraged the mainland politicians, bureaucrats, financial investors, film-makers and film critics to play a dominant role in local cinema. Hong Kong films were evaluated by mainland politicians and cultural critics in terms of China’s national politics and society. As a consequence, Hong Kong cinema in the first half of the century mirrored the generalised Chinese community – its tensions, conflicts and ambiguity in the filmic construction of Chinese national identity.

This chapter is organised into four sections. While the first section examines the British colony in the context of the triangular relationship, the other three sections discuss the Hong Kong film industry, its film products and film criticism according to Higson’s four approaches to national cinema. Thus, the second section deals with the production-centred film industry and its film markets. The third section explores the idea of Chinese nationhood in Hong Kong film texts. The final section discusses how film criticism in Hong Kong shaped Hong Kong cinema as part of Chinese national cinema in the first half of the century.

Minimum intervention and Chinese nationalism

Freedom of movement between the colony and the mainland made Hong Kong in the first half of the century a quite different place from later. Before 1950, the colonial government did not impose restrictions on entry to the colony, nor did the Chinese government prevent mainland Chinese from working and living in Hong Kong. As a result, Hong Kong’s population was influenced by political and economic changes on the mainland. Within the colony, the British coloniser ran a dual political and social system to differentiate two distinct communities, the British and the Chinese. This system encouraged local Chinese to seek identification with the mainland for a sense of belonging and security. At the same time, the mainland Chinese actively encouraged the Hong Kong Chinese to make a contribution to the Chinese nation-building programmes on the mainland. Within this historical context, Hong Kong could hardly be perceived or imagined as a distinct community of its own either by the British coloniser, the mainland Chinese or by the local Chinese.

From the very beginning, the British coloniser believed that the colony’s British and Chinese subjects should be governed differently. In his first public proclamation in January 1841, the first governor of Hong Kong, Captain Elliot, stated that, ‘all natives of the island and all natives of China resorting thereto, were to be governed according to the [British] laws’, but only people ‘other than natives or Chinese’ would enjoy full security and protection according to the principles and practice of British Law (Endacott 1958: 26–7; Eitel 1968: 164–5). His proclamation laid the basis for the coloniser to practise two different codes of law in the early period of Hong Kong.

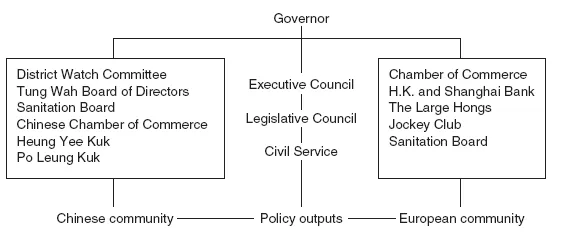

Within the economic expansion of Hong Kong the local population increased, as more mainland Chinese arrived at the British colony. With Britain’s further annexation of the Kowloon peninsula in 1860, the colony developed into a prosperous trading port and, at the same time, a society with a high rate of crime and triads membership (Lethbridge 1978: 62). A handful of colonial public institutions was no longer capable of coping with the increased population and the maintenance of political and social order. In the late nineteenth century, the colonial government developed a structure based on Elliot’s bifurcated system to allow the local Chinese to manage their own political and social affairs ‘without passing them the practical powers of tax collection and military forces’ (Tsai 1993: 290). Tung Wah Hospital, Po Leung Kuk (the society for the Protection of Women and Girls) and the District Watch Committee were established for the provision of social services. However, with the consent of the colonial government, these organisations ‘extended their scope of activities beyond charitable work to include the management of public affairs in Hong Kong’ (Tsai 1993: 69), to perform as a Chinese court and to function as a Chinese Executive Council. The division into two communities was reinforced again through racially based administration. Ian Scott (1989: 62) charts this colonial structure from late last century to the late 1960s as shown in Figure 1.1.

The dual system of law and administration encouraged the local Chinese to differentiate themselves from the colonial government and the British community. They practised their own cultural traditions and religious beliefs, and relied on their close connection with the mainland culturally, economically and politically. As the wealthy Chinese merchants suffered from racially based legislation in residence, education, public health and other matters (Wesley-Smith 1994: 91–105), they were encouraged to strengthen their ethnic, cultural and political connections with China. Additionally, their connection with China, in some cases, brought them official appointments from the colonial government, which in turn elevated their social status in the colony. However, in return, the mainland Chinese also required them to be loyal to China through financial and political contributions (Tsai 1993: 65–102).

Figure 1.1 The colonial structure of Hong Kong up to the late 1960s

Freedom of movement enabled the mainland Chinese the right to access the colony. It made Hong Kong not only a place for economic adventure but also a place for conducting political activities forbidden on the mainland. In the 1850s, less than a decade after the British colony was founded, the anti-Manchu Taiping movement drove many wealthy Chinese in the south to the colony and, later, Taiping rebels and revolutionaries themselves also sought political refuge in Hong Kong (Yuan 1993: 114). In the latter part of the last century, Dr Sun Yat-sen and republican revolutionaries developed their ideas on overthrowing the Qing Dynasty in Hong Kong. The colony was crucial in the republican revolution in terms of gaining financial support from overseas and in providing an exile base for the mainland rebels and revolutionaries.

With support from the local Chinese community, Hong Kong continued to play an important role in Chinese national politics. Between 1912 and 1913 the local Chinese organised a 3-month tramway boycott to protest against the colonial government banning the use of mainland coins in Hong Kong. They regarded the decision as ‘an unfriendly act and highly disrespectful towards the new republic’ (M.K. Chan 1994: 29). A similar popular nationalism was also shown in the support of the local Chinese of the May Fourth movement, and in their participation in the boycott of Japanese goods in 1919 and the Seamen’s Strike in 1922. Organised by the Guomindang and the Chinese Communist Party in 1925 and 1926 as part of the nationalist movement against British imperialism, thousands of Hong Kong workers left Hong Kong for the mainland to join the by then 18-month long Canton-Hong Kong General Strike. The strike paralysed business and trade in Hong Kong to a degree that almost ruined British interests in South China.

Japan’s invasion of China strengthened the Chinese nationalism in Hong Kong. During the 1930s, mainland nationalists, including left-wing cultural workers, the Communists and Guomindang supporters, went to Hong Kong to promote the anti-Japanese war. Apart from the period of the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong between 1941 and 1945, the colony again functioned as a base for mainland Chinese to gain overseas financial support and to conduct political activities that would have endangered their lives on the mainland. After the British regained the colony in 1945, the population in Hong Kong increased dramatically. Tens of thousands of mainland refugees arrived in the colony, including those cultural workers who had worked and co-operated with the Japanese during the Japanese occupation of Shanghai. A large group of mainland Communists and left-wing activists also came to Hong Kong to promote the anti-Guomindang movement. After the Guomindang lost their battle with the Communists for control of the mainland, another wave of mainland political and economic refugees arrived in Hong Kong. From 1945 to the mid-1950s, over one million mainland Chinese migrated to Hong Kong (Hong Kong 1956: 3). These included Shanghai capitalists, wealthy merchants, professionals and labourers from the nearby area of Guangzhou. Consequently, mainland national political culture was transplanted to and intensified in the colony.

The British colony, Hong Kong, was founded to serve the interests of the British. At the same time, however, the mainland Chinese also used the colony to further China’s interests. The colonial dual system and China’s involvement with the colony encouraged the Hong Kong Chinese to seek belonging, security and authenticity from the mainland and, therefore, to identify themselves as part of the Chinese nation through progressively strengthening ethnic ties, cultural tradition and mutual political and economic needs. In the context of its part in a triangular relationship in the first half of the century, Hong Kong was unable to develop its own cultural identity that could resist mainland’s nationalism.

National politics and the mainland market

Before the Chinese border was closed in 1950, and before mainstream Hong Kong films were banned in China from 1952, the Shanghai film industry and the Hong Kong film industry shared similar film markets, production modes and film talents. At the time, South China and Macau formed about 80 per cent of the foreign market of Hong Kong films, with 10 per cent coming from Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaya and Indonesia (Leung and Chan 1997: 143), and 10 per cent from Chinese enclaves in Western countries. According to the Hong Kong film historian Yu Mowan (1994: 88–99) two-thirds of Hong Kong film directors were originally from Shanghai. These film-makers directed more than half of the Cantonese films before the Second World War. From the late 1940s to the 1950s, one third of Cantonese films were also directed by mainland filmmakers. Despite its reputation as a centre of Cantonese film production, the Hong Kong film industry was shaped by and mirrored mainland national political concerns through its interaction with the Chinese national government, the Shanghai film industry, the left-wing and Communist film-makers and cultural critics.

The British colony played an important role in the early construction of Chinese national cinema. With a considerable financial input from Hong Kong in 1929, the first Chinese film enterprise, operated in the form of a national integrated trust, Lianhua Production and Printing Limited, was established in Shanghai by two Cantonese, Luo Mingyou and Li Minwei. With a family business across Guangzhou and Hong Kong, and close family connections with the Guomindang government, Luo Mingyou was known as the first Chinese to own a chain of cinema theatres in North China in the 1920s (Zhu and Wang 1991: 70–2). Born in Japan from a Chinese rice dealer family in Hong Kong, Li Minwei was one of the early Chinese film pioneers in Hong Kong, and a strong republican supporter (Gong 1962: 123–138; Zhong 1965: 20). He made the first Hong Kong film, Zhuangzi shi qi / Zhuangzi Tests his Wife, in 1913, produced the first Hong Kong feature film, Yanzhi / Rouge, in 1924, and built the first Hong Kong film studio in 1925. He also filmed a number of newsreels about Dr Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary activities in China. As a result of the Hong Kong-Canton General Strike in 1925, the small Hong Kong film industry, which had produced fewer than fifteen movies between 1913 and 1925 collapsed. In the aftermath of the strike, Li Minwei, like most Hong Kong filmmakers, left the colony for the mainland. In 1926, Li transferred his company, Minxin, to Shanghai.

While film-making in Hong Kong was at a standstill between 1925 and 1929, Li Minwei and his business partner Luo Mingyou planned to develop a centralised national film industry with its headquarters set up in Hong Kong and a production centre in Shanghai. They invited the most wealthy and politically influential Chinese person in the colony, Sir Robert Ho Tung (He Dong), to be the chairman of the Lianhua Executive Board. At the same time, they also gained the support of a number of financial investors, including Guomindang bureaucrats, merchants, film producers, distributors and exhibitors from Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai and Zhejiang province (Cheng 1966: 147). Lianhua controlled six film studios, with four located in Shanghai, one in Hong Kong and one in Beijing. As Shanghai was the production centre, the film industry’s headquarters moved to Shanghai a year later.

Responding to the Nanjing government’s agenda of anti-imperialism and anti-feudalism, Lianhua aimed for a centralised national film industry which would resist ‘feudalist’ films from the Chinese domestic film industry, and non-Chinese films, especially from Hollywood. In its ten trade and business principles drawn up in 1929 (and reproduced below), Lianhua detailed its relationship with the national government, other national business sectors and the national community (Du 1986b, vol.1: 82–3).

- Renovate the national cinema. Diminish the trend of superstition and violence in current national films.

- Use film as a tool for mass education. Bring films to the country and hinterland areas. Produce more educational documentary films.

- Serve the industry; maintain and defend the benefit of Chinese film exhibitors through mutual assistance. Encourage those Chinese exhibitors reluctant to project Chinese movies to change their minds.

- Resist the cultural and economic invasion of non-Chinese films. Promote national, intrinsic virtues, and direct the national cinema against alien culture. Unite Chinese theatre-owners to purchase non-Chinese theatres to show more Chinese films to block the economic invasion of foreign films.

- Train more people to involve themselves in the Chinese film industry. In particular, pay more attention to recruiting the talents of various types into the industry, avoiding ‘stealing’ personnel in the same field. When there is a need, establish a national film school.

- Assist national undertakings, and co-operate with industrial entities owned by Chinese. Where possible, we must foster our national products through films, encouraging people to consume more national products in order to assist our industry.

- Develop the overseas market, promoting Chinese national films first in the South-East Asian region, and then in European and American markets.

- Uphold the rights of film-makers, cultivate the professional consciousness of the film-makers, and clear up society’s misconception of and prejudice against film-makers.

- Establish a centre for film production. From the very beginning, we must adopt a system of collaboration within the sectors and, later on, link them together to establish a Chinese movie centre.

- Make a contribution to the nation and to society. Use film to promote government policies. If necessary, set up services in various places.

However, the introduction of sound into film complicated Li and Luo’s intention of treating the colony’s film industry as part of Chinese national cinema, as sound technology highlighted the linguistic difference between Cantonese and Mandarin. In 1933, the first Cantonese film Baijin Long / White Golden Dragon was produced in Shanghai by Tianyi, one of the three major film studios in Shanghai at the time. The economic success of the film in South China encouraged Tianyi to establish a Cantonese film production company Nanyang in Hong Kong in the following year. Founded in 1924 and managed by four brothers from the Shaw (Shao) family, which included the well-known Chinese film tycoon Run Run Shaw (Shao Yifu), Tianyi was the most commercially successful film production company, and the ...