1

THE SYSTEM DISSOLVES

The summer of 1971 ushered in a period of economic crisis for the United States that had its origins in the Vietnam War and the free spending habits of the 1960s. After several decades of unparalleled growth, the American economy had developed both a growing inflation rate and growing unemployment at the same time. The reaction in the international financial markets caused strains that would rapidly contribute to a new emerging world financial order. In this new order, sterling was rapidly declining in importance while the yen and the Deutschmark were rising. The dollar remained the premier reserve currency but was under attack by traders who assumed that its value was bloated in comparison with other hard currencies.

The new emerging order would also place the United States in an embarrassing position. In the twenty-five years since it had signed the Bretton Woods Agreement in New Hampshire in 1947, the country had experienced unequalled prosperity. The standard of living had increased, the population had grown, higher education had become more accessible to greater numbers of people and the dollar had become the undisputed international reserve currency. How much the Bretton Woods Agreement itself had to do with America’s success was not as much an issue as the fact that it would soon unravel, leaving the international financial markets in turmoil and changing the role of the United States in the world economy. The disintegration unleashed forces to which the country was unaccustomed after decades of economic success.

Since 1945, the dollar had been the pre-eminent currency in the world and had no challenges from any other currency. During that time, world trade patterns had evolved into currency blocs, with many countries tying their currency, and their fortunes, to the currency of their major trading partner. The Deutschmark had come to dominate Europe, excluding Britain, while the yen dominated parts of Asia and sterling remained central to many Commonwealth currencies. But the dollar maintained the dominant position among them, accounting for about 70–75 per cent of the worlds foreign exchange reserves. Within the parity system constructed at Bretton Woods, the dollar was the sovereign currency.

In Britain, the unravelling of the agreement would lead to several international embarrassments centring around the pound and finally would lead to the acknowledgement that Britain was no longer a world power. In both cases, there was more than a subtle irony at work. Post-1971 economic forces had brought the two economic powers to heel although certainly in varying degrees. The irony was that forty years before, the unilateral actions of each had contributed to economic mayhem during the Depression. It was those unilateral actions that had caused the original Bretton Woods system to be constructed in the first place. Four decades later similar forces were again at work.

Before 1947, the last time that the major trading nations had had an orderly market for foreign exchange was in the 1920s. The dollar and sterling adhered to what was known as the gold exchange standard. Under that system, each currency was given a specific value in gold, which in turn was used to settle official claims among nations. The system worked well during the 1920s but after the stock market crash of 1929 and the Depression that followed, the lack of a central authority to administer it became obvious. No one central international institution was established possessing mediatorial power to settle international financial disputes. While many would be instituted during the Depression, they would not be fully appreciated until after the war had ended.

As unemployment grew in the industrialised countries and exports began to fall for lack of demand, both Britain and the United States devalued their currencies in order to make exports cheaper. The problem was that the actions were essentially unilateral and almost totally nationalistic; the best way to invigorate trade was to devalue, usually angering other trading partners in the process. The devaluations were a contributing cause of the Depression itself, hindering trade rather than fostering it. The international trade problem led to the establishment of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, or GATT, in 1934. The currency problem was addressed later, first in 1940, but the Second World War intervened and it was not until 1944 that meaningful progress was made toward constructing a system that would help prevent problems in the future.

Arguments for and against the Bretton Woods system had always existed but one point remains undisputed: the foreign exchange system has been significantly more volatile without its fixed parity system to guide it. For better or worse, freely floating currencies have contributed immeasurably to the financial chaos that has reigned since 1972, especially during the period 1981–85. Yet at that time, the demise of the system built by the Allies immediately after the war suggested nothing but darkness and uncertainty. The last vestige of gold, once the centrepiece of foreign exchange values, was gone forever. With one stroke of the pen, Richard Nixon helped sink a system that had pulled the Western economies up by the bootstraps after the war and given them a semblance of order after almost fifteen years of unmitigated chaos in the 1930s and 1940s.

The original idea behind the Bretton Woods Agreement was simple yet devilishly political at the same time. The two major architects of the new monetary order—John Maynard Keynes of Britain and Harry Dexter White of the United States—realised that the new system would have political ramifications as well as economic ones. Yet if the two could be linked tolerably, the political temptations against acting unilaterally would be discouraged. Unlike the Depression years, the major economies would now have to recognise the shortcomings of acting purely in their own interests.

All currencies were given a parity value in terms of US dollars, itself given a distinct value against gold. Currencies were then allowed to fluctuate plus or minus 1 per cent against the parity value. If the market forces pressured a currency above or below its allowed band, the country itself would have to intervene by buying or selling its currency in the markets to return it within the allowed limits. The values were well understood and the system worked tolerably well until market forces dictated that new values be imposed.

The newly constructed system did not emerge immediately. Until 1959, the hard currencies were all protected by controls and convertibility was still impractical. The foreign exchange market was ruled by monetary authorities which dictated fixed prices for their currencies, making the notion of fixed parities within trading bands seem somewhat distant. Britain made an attempt to float the pound in the 1950s only to find itself short of foreign exchange reserves within a very short period of time. The market in the 1950s would only cast a vote of confidence in currencies backed by substantial reserves and a solid international trading position—a position that most countries would take time to achieve after the war.

When parity values became unrealistic, monetary authorities would consult with the IMF to determine new values. The IMF itself was a progeny of the Bretton Woods Agreement along with its sister institution, the World Bank. Its major purpose was (and still is) to make loans to members who experience balance of payments problems. When such problems became intolerable, putting a country’s exchange rate under pressure and affecting its import/export position, the IMF would help arrange a devaluation or revaluation of the currency’s parity value. Devaluation meant that the value would fall while revaluation meant a rise. In either case, the political consequences at home could be quick and unpleasant.

Devaluations mean that a country’s exports become cheaper while imports become more expensive. Revaluations cause the opposite effect. Politically, devaluations are something of an embarrassment to authorities because they are usually interpreted as signs of weakness in an economy. Revaluations, on the other hand, suggest strength in the domestic economy but can lead to adjustments in the future unless the economy continues to move ahead strongly, shaking off the effects of stronger currency and more expensive exports.

When a country required a change in its parity value, the other members of the IMF would have to be consulted in order to avoid disagreement and any potential retaliation by other trading partners. In the early 1930s, both Britain and the United States acted alone at different times in declaring a devaluation of their currencies in vain attempts to stimulate exports and stem imports. Their actions were fruitless but the political ramifications were felt long after the Depression ended. Unilateral devaluations were one of the major problems the Bretton Woods Agreement sought to prevent in the future.

But whether done in consultation or alone, devaluations were embarrassing. Since the Agreement was signed, Britain underwent several devaluations of sterling. In 1947, the pound traded at $4.80. By 1971, its value had eroded to $2.40, the sort of fall that ordinary market drift could not account for over the years.The most recent devaluation prior to 1971 was in 1967 when Prime Minister Harold Wilson had announced a 15 per cent adjustment. Equally important was the effect that the various devaluations had on Britain’s reputation as a world power. By 1968, after the devaluations, the Suez Crisis of the previous decade and the spate of independence ceremonies following the break-up of the old colonial empire, it became apparent that Britain’s hold over world affairs, both economic and political, had faded.

The 1967 devaluation came in a time of deteriorating economic conditions. Upon taking office in 1964, the Labour government had presided over a strong economy that had seen strong industrial production, a surge in the GNP, and relatively low inflation and wage demands. But over the next three years, conditions deteriorated markedly. By 1967, wage demands had shot up, inflation had risen, and President de Gaulle of France had effectively sabotaged Britain’s potential entry into the European Community. The thought of devaluation was not a pleasant one for Wilson’s government but, then again, it was not an alien idea either. Britain had undergone devaluations before and the new pressures developing in the markets made it clear that the pound needed to undergo an adjustment.

In the months preceding the actual devaluation announcement of November 1967 Britain had unsuccessfully used many of its standby facilities that normally are used to shore up a currency. The swap arrangements with the Federal Reserve and other major central banks were employed but sterling still floundered in the markets. Much attention was paid to the ‘international speculators’ cited by many politicians and Treasury officials as the cause of sterling’s weakness. This has always been a method used to blame anonymous elements in the markets for a currency’s troubles and it was amply used in the months preceding November. The British avidly used the term coined by a Treasury official several years before, referring to the traders and speculators as the ‘gnomes of Zurich’. Somewhere in the money houses of Switzerland were little money grabbers bent on forcing down the value of the pound.

The devaluation announced in November did not end Britain’s problems in the foreign exchange markets but it did provide a temporary palliative. Although the actual decision to devalue was Britain’s alone, consultations had been taken with its major trading partners and the IMF prior to Prime Minister Wilson’s announcement. Yet despite the measures, within a decade the pound would again be under serious pressure due to the effect of a miner’s strike in 1974 and other work stoppages that did little to enhance Britain’s reputation internationally. Under the Labour government of Harold Wilson and, later, James Callaghan, Britain developed a cranky reputation as a place where little was done but at a high cost nevertheless. This would again cause a flight from sterling that would require IMF assistance in the near future.

The next currency to suffer serious problems would be the dollar, the central numéraire of the IMF fixed parity system. As will be seen, the official reaction of the United States was not dissimilar to that of Britain. Politically, someone else would have to be blamed for the plight of the dollar. The money inflation created by financing the Vietnam War and the failure of Lyndon Johnson to balance the budget in 1968 made the dollar less appealing to traders and others who had the option of seeking other currencies in which to direct their ‘hot money’ flows.Their activities would provide a convenient excuse for the actions of August 1971 that so drastically changed the structure of the international financial system.

THE CAMP DAVID DECISION

The Bretton Woods Agreement concerning the fixed parity system came to an abrupt end on the evening of 15 August 1971. In a televised news conference, President Richard Nixon announced measures designed to curtail the inflation rate and aid the balance of payments, which was showing a deficit. Although the decision to end the convertibility of the dollar into gold for official purposes was without doubt the most momentous part of the economic package, it certainly was not announced first in the address. In fact, it was the last part of the anti-inflation package to be mentioned.

The Nixon administration was compelled to act against inflation for several reasons. Wage demands had grown substantially in the late 1960s. After a seventy-day strike, car workers at General Motors had negotiated a 20 per cent wage increase. Large increases were also found in the construction industry, just beginning to feel the benefits of the new housing policies of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Yet, at the same time, unemployment stood at 6 per cent and showed no signs of receding. Although the United States was the largest foreign investor in the world (direct foreign investment), American tastes for foreign produced goods had steadily increased since the Second World War and was now contributing to the trade imbalance and balance of payments deficit.

Other economic indicators also were showing signs of nervousness and inflation.Treasury bond yields were near 8 per cent and the Dow Jones index was hovering in the 700 range after Nixon took office. Despite his optimism that ‘now was a good time to buy’ stocks, investors tended not to believe.This was disappointing because conventional wisdom held that Republicans were good for the stock market while Democrats tended to depress it with their free spending policies. Moreover, the first Nixon administration did show signs of traditional Republican thinking by being preoccupied with international rather than domestic affairs. The Vietnam War consumed much of the administration’s time but re-election year was not far away and the domestic economy required attention.

The details of the 15 August announcement were finalised at the Camp David retreat immediately before the televised address. A devaluation of the dollar had been rumoured for some time. Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing of France had suggested it earlier in the year although the Americans steadfastly had maintained that devaluation was not an option for the administration. Governor John Connally of Texas, Nixon’s Secretary of the Treasury, had stated emphatically as late as May that devaluation would be resisted and that the price of gold would remain stable. Equally, Connally maintained that wage and price controls would not be implemented although Arthur Burns, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, had suggested just such a course of action. Clearly there were divergent views on the best method to combat inflation.

The divergent views finally came together on the weekend of 12–15 August as the administration announced measures designed to reduce unemployment and inflation. As Nixon laid out his plan in the televised address, domestic considerations came first. All of the measures announced were implemented under the Economic Stabilisation Act of 1970. He announced a 10 per cent ‘job development’ credit, or tax credit for capital investment by industry. He also repealed the 7 per cent excise on motor cars then in effect while insisting that the car industry pass on the savings to car buyers. He also ordered a $4.7 billion cut in federal spending and a 5 per cent pay cut for government employees. Finally, on the domestic side, he ordered a ninety-day freeze on all wages and prices in the country.

On the international side, the measures were equally stringent. US foreign aid was ordered to be cut by 10 per cent. But the measures designed to protect the dollar were saved for last. Acknowledging that the dollar was under intense pressure in the foreign exchange markets, there was little doubt who would be blamed for the problem:

In the past seven years, there’s been an average of one international monetary crisis every year. Now who gains from these crises? Not the working man, not the investor, not the real producers of wealth. The gainers are the international money speculators: because they thrive on crisis, they help to create them.1

Following this statement, Nixon announced that he had ordered the United States to halt the convertibility of the dollar into gold for official purposes.

The final measure announced was a temporary 10 per cent tax on all imported goods, designed to dilute American enthusiasm for imports. Taken in its entirety, the package was designed to be only temporary. But the dollar part was purposely left more vague. ‘In full cooperation with the International Monetary Fund and those who trade with us, we will press for the necessary reforms to set up an urgently needed new international monetary system,’ Nixon concluded. ‘I am determined that the American dollar must never again be a hostage in the hands of international speculators.’2 As it turned out, all of the other measures either would be repealed or expire. The dollar convertibility issue never would be resolved.

At the time, the dollar devaluation was seen in context with the other measures rather than taken on its own. The Economist noted that the incomes policy was of paramount importance: ‘The devaluation of the dollar was welcome and overdue, but it will have been dearly bought if one of the prices turns out to be another devaluation of the idea that a sensible incomes policy really can be made to work.’3 Apparently, no one thought that the devaluation would lead to a total dismemberment of the fixed parity system within a year.

From the moment of the announcement, the currency markets plunged into turmoil. When other currencies were revalued or devalued, adjustments were certainly made in the markets but when the central currency of the entire system was devalued, momentary chaos certainly could be expected.

The effects of the dollar devaluation were felt almost immediately. Most commentators were immediately concerned with the trade and balance of payments effects of the measures on the international side and the price and employment effects at home. Overlooked in Nixon’s statement and in many of the immediate commentaries thereafter was the effect of the dollar devaluation on the financial markets. A cheaper dollar dissuaded many foreign investors from American portfolio investments and many took action to shift their funds away from the dollar into other hard currency financial markets. In the early 1970s, the choice was still relatively limited. The United States and Britain possessed the two largest stock markets at the time as well as the two largest government bond markets.

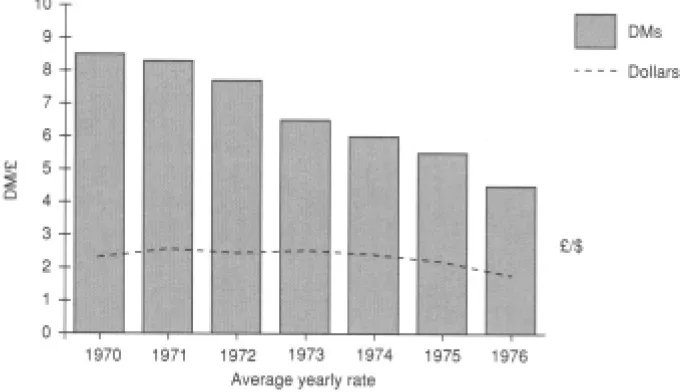

Figure 1.1 Sterling v. dollar and Deutschmark, 1970–76

Source: Central Statistical Office, Financial Statistics, various issues

The decline of the dollar was shadowed by a rise in sterling. The pound moved up immediately after the 15 August announcement by about 2.5 per cent and remained in a higher range for the balance of the year. The Bank of England took preventive measures to protect the pound from even further rises and to protect it from flight capital coming out of dollars but the currency still remained strong. Being protected by exchange controls at the time, sterling was relatively easy to protect while the dollar continued its slide. The behaviour of the pound compared to the dollar and the Deutschmark can be found in Figure 1.1. It should be noted that the pound was able to maintain itself against the dollar before and after 1971 but was less successful against the Deutschmark.

One indication of fears for the dollar surfaced as early as 1969 when the IMF sanctioned the use of special drawing rights, or SDRs, to be used by its member states in official transactions. The SDR was (and is) a basket currency based upon a weighted average of other currencies. Originally, it included over a dozen of the major trading currencies although currently it contains only five.4 Using the weighted concept, the IMF was able to construct a currency that was less subject to swings in the dollar. If the dollar declined then the other currencies would appreciate, mitigating the movement of the major reserve currency. In short, the SDR was less volatile than any one of its individual c...