1 Greek vases for sale: some statistical evidence

VINNIE NØRSKOV

INTRODUCTION

In 1993, the market for Greek vases reached a new peak when a Caeretan hydria from the Hirschmann collection was sold for £2.2 million at Sotheby’s in London (9.12.1993, lot 35). This hydria is but the latest sign of the entry on to the classical antiquities market of ‘investment collecting’ (Herchenröder 1994). This new kind of collecting first appeared in the field of antiquities in the 1970s, probably stimulated by the well-known story of the ‘One-Million-Dollar Vase’: the Euphronios krater acquired in 1972 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Meyer 1973: 86–100; Hoving 1993: 307–40). During the 1990s, reports from the antiquities market (as found, for instance, in the magazine Minerva) testify to the increased number of record prices over the last ten years and suggest that investment collecting has become more common. This development has been greeted by alarm bells – rung by scholars and others who see a connection between high prices on the art market and the illegal excavation and trade of antiquities.

This is all well known but there have been, surprisingly, few attempts to analyse the actual market situation, perhaps due to a fear of ‘contamination’ among archaeologists working in related areas. However, in consequence, it is now impossible to research into the modern collecting of antiquities without also considering the source of the objects. This chapter considers the field of Greek vases and approaches the phenomenon from two different angles in order to understand the different mechanisms at work. The aim is to investigate the development of the art market in order to see if certain changes on the market can be detected and explained. This has been done in two ways. First, from the perspective of the seller, through an analysis of the actual market supply, and, second, from that of the buyer, through studies of eight selected collections, of which one is examined in detail.

First, however, the relationship between the market and archaeology must be considered, as this is the premise for the entire work – the idea that the market and its consequences of clandestine excavation and illegal trade cannot be examined as an independent phenomenon but as part of the larger society, which also comprises archaeologists and their field of study. The argument is that several recent changes must have influenced the field of antiquities collecting. Among these changes, three seem to be of major importance: (1) classical archaeology has developed into what has been called the phase of contextual archaeology; (2) ethical behaviour concerning objects offered on the market has changed; and (3) collecting ancient art has become a strategy of investment.

The Euphronios krater in many ways symbolizes these changes in the history of collecting Greek vases. When the Metropolitan bought the vase in 1972, it was claimed that it came from an old collection. A few months later the New York Times revealed that European scholars believed the vase to have derived from a recently looted grave in Cerveteri. An Italian tombarolo confessed to its discovery. The Metropolitan then stated that it had bought the vase from an intermediary acting for a Lebanese dealer who said that it had been in his family’s possession since 1920. Since then, the true origin of the vase has never convincingly been explained, but the fact that a museum had bought a vase with a very dubious provenance and at such a high price shocked the archaeological world. This was just two years after the 1970 UNESCO Convention had been adopted. The following year, in 1973, Karl Meyer published his famous book The Plundered Past where several similar stories were brought to light, together with some scary evidence concerning the production of forgeries of Greek vases.

Historically, it is noticeable that new trends and interests in research have often had a direct influence on the development of collecting. This is because collecting involves three ‘actors’: the dealer, the collector and the specialist. Art is no mere luxury good, and the specialist is an essential part of the triangle because he or she is required to authenticate and evaluate the objects. Many of the finest vase collections were assembled because of a close relationship between a collector and an archaeologist – the latter often being the primus motor. Seen in this light, the importance of the interconnection between collecting and research is clear.

The new ethical standards being adopted among classical archaeologists, together with the development of a contextual archaeology, have put the cooperation between the three actors to a difficult test. However, it still exists in the museum environment and will continue to do so as long as the museums acquire on the art market. Many museum curators also have close contacts with collectors, and the museum can be considered the main meeting place of the three actors.

A LOOK AT THE MARKET

An analysis of the antiquities market would ideally encompass the entire market. However, although the market was, until recently, limited to a smallcircle of collectors and museums, it does nevertheless comprise a considerable number of objects. For this reason the present study concentrates on Greek vases. Besides coins – which are a special case – Greek vases constitute the largest group of classical antiquities on the market. In addition, they have, in the past, been appreciated for several different reasons and their painted decoration has long made them cherished objects among private collectors.

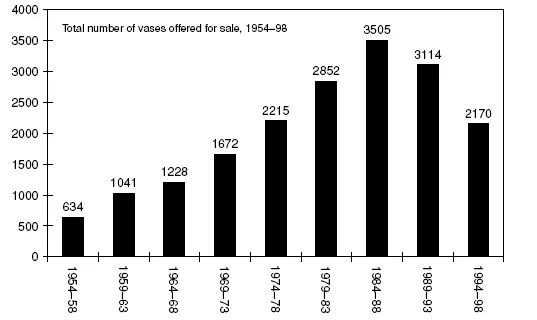

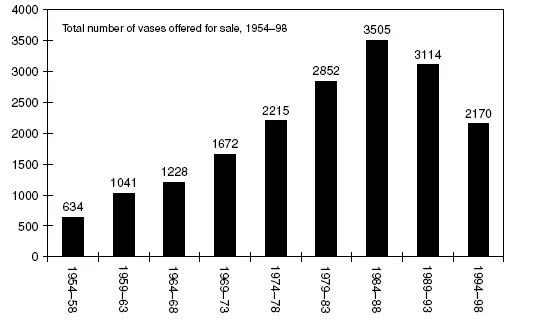

The development of the market for Greek vases has been studied through a statistical analysis based on 597 auction catalogues and gallery publications from the years 1954–98. Figure 1.1 shows the number of vases appearing on the market during this period, 18,431 in total, with a gently rising, regular curve peaking in the 1980s. Figure 1.2 compares this total number with the number of catalogues used in the analyses. Ideally, the number of catalogues printed each year should be included, but this information is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain. Catalogues published by Christie’s and Sotheby’s account for about 70 per cent of those consulted. The chart shows a positive correlation between the number of catalogues and the number of vases, but the average number of vases per catalogue has also increased during the last twenty years, which shows clearly that the total number of vases actually on the market increased during the 1980s.

The last period shows a decrease in the number of vases but also of catalogues studied. As the average number of vases in each catalogue remains pretty much the same, it seems that the decrease is not too significant. It should be mentioned, however, that there have been fewer auctions in total since Sotheby’s stopped their London sales in 1997.

Figure 1.1 Total number of vases offered for sale, 1954–98

Figure 1.2 The number of vases offered for sale 1954–98 related to the number of catalogues used in the analysis

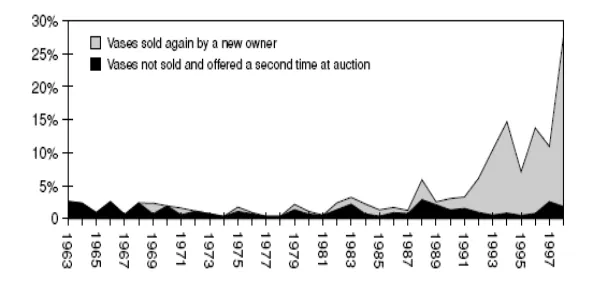

Figure 1.3 Percentage of vases offered on the market more than once, 1963–98

The third chart, Figure 1.3, illustrates the percentage of vases offered for sale which had previously appeared on the market. The black group constitute vases not sold at first auction and therefore offered again, a group normally termed bought in. The percentage shown should be considered a minimum – comprising only those recognized in catalogues. Auction houses do not mention in catalogue descriptions whether an object has been offered before but failed to sell. Thus it is often sheer luck when a vase offered up for sale again in this way is recognized, particularly as very few vases were illustrated in early catalogues. The grey group constitutes vases which had been sold in earlier auctions. Clearly, there is a marked increase in this group through time. Interestingly, this information is always given under the heading ‘provenance’.

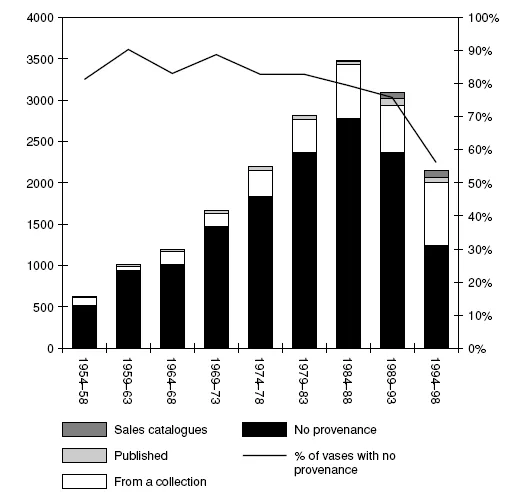

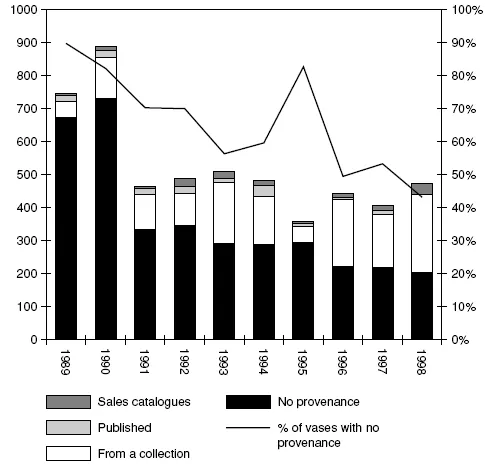

This leads to the next set of charts, which illustrate the provenance of the vases. It must be stressed in this context that the term ‘provenance’ has nothing to do with archaeological provenance, but that it is the art market term for the modern history of an object. Figure 1.4 shows that from the 1950s onwards, about 80 per cent of the vases offered lacked any information on provenance. By the late 1980s/early 1990s, this figure had fallen to just above 75 per cent, but then there seems to be a further, recent, drop, as the last period (1994–98) shows that only 58 per cent of the vases lacked information on provenance. In Figure 1.5 the last ten years have been singled out, and except for 1995 there is a steady trend downwards. This must be seen as a positive development, and it becomes even clearer, when looking at the next set of charts, which show what types of vases have been offered.

Figure 1.4 Provenance of vases offered on the market, 1954–98

Figure 1.5 Provenance of vases offered on the market, 1989–98

In order to make the statistics reasonably clear, a major part of the vases have been divided into five larger groups. These groups are formed using stylistic and chronological criteria. The Corinthian group comprise Protocorinthian, Corinthian and Italo-corinthian vases. The black-figure group includes Attic, Boeotian, Laconian, Chalcidian and Etruscan black-figure vases. The whiteground and Attic red-figure groups are restricted to these two eponymous types of vase. The South Italian red-figure group includes Apulian, Campanian, Paestan, Lucanian and Sicilian as well as generic South Italian vases.

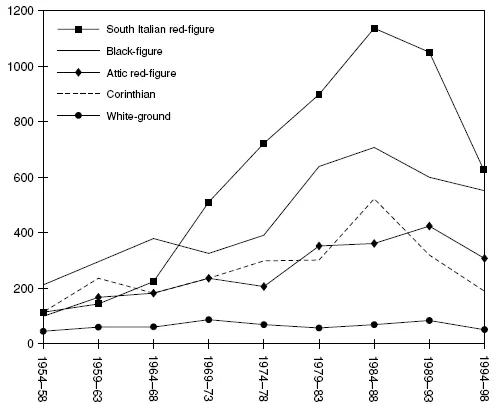

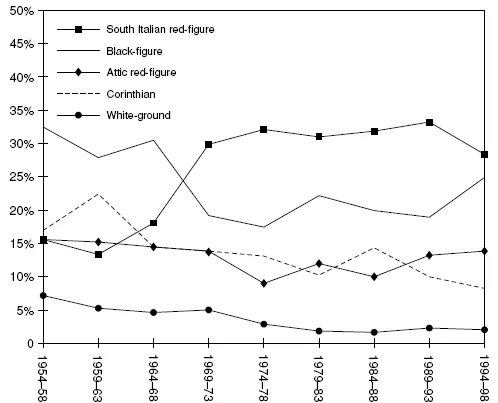

The charts in Figures 1.6 and 1.7 show for each group the number and relative percentage of vases offered for sale. Two important developments are to be stressed: during the first 15 years, until the late 1960s, Corinthian and black-figure were the most important groups, comprising together more than 50 per cent of the market. Then, from the late 1960s, the number of South Italian red-figure vases increased rapidly, and from then until the early 1990s they constituted more than 30 per cent of the total supply. The most reasonable explanation of this increase is that it is a result of clandestine excavations in South Italy and especially in Apulia, as for example illustrated in the travelling exhibition Fundort: unbekannt (Graepler 1993). Comparing this result with Figure 1.1 (which shows that the overall increase of vases on the market was largest in the 1980s), it seems clear that the market growth during this period was fuelled by tomb robbing in Apulia. The only other possible explanation would be that the market was flooded by forgeries, and although there are some scholars who are inclined to prefer this explanation, it still remains unproven (but see Paolucci 1995: VII).

Figure 1.6 Distribution of five selected groups of vases, 1954–98 (total numbers)

It is interesting to note, however, that the number of South Italian vases on the market has decreased dramatically in the last five years, not only in number but, more importantly, also in percentage. This suggests that there is a real decrease in supply and that it is not only because a smaller number of catalogues has been consulted. This decrease could be a reflection of the intensified and successful work of the Italian police, who recovered quite extensive depots of archaeological objects during the 1990s (Graepler 1993: 56).

Before turning to the museum studies, one curiosity should be mentioned: a striking result of the investigation is that the market has offered more Attic black-figure vases than red-figure vases during the entire period (Figure 1.8), yet the known corpus of Attic vases shows a much larger proportion of redfigure than of black-figure (Boardman 1974: 7). How is this inverted pattern of the market to be understood? Perhaps it is because the antiquities market is much larger than can be investigated on the basis of auction and gallery catalogues alone. If so, it means that a large number of red-figure vases have been sold on what could be called the ‘invisible’ market. An aforementioned example is the Euphronios krater in New York.

Figure 1.7 Distribution of five selected groups of vases, 1954–98 (percentage)

Such an interpretation has further implications. It might be possible that many of the vases from South Italy are a kind of ‘windfall’ for the tombaroli. Since the early 1980s one of the largest private collections of ancient armour has been formed by a German collector (Graepler 1995: 70–1) and it is possible that tomb robbers in Apulia and elsewhere were not, in fact, primarily looking for vases, but for armour, which had a ready ‘buyer’. The exi...