- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Alternative Narratives in Modern Japanese History

About this book

How did ordinary people experience Japan's modern transformation? What role did people in local areas play in the making of modern Japan? How do studies of local politics help explain national events?

The dominant account of modern Japanese history focuses on the nation-building that brought Japan into the modern world. After centuries of isolation, American warships forced Japan to open its doors to the West and a group of tough new leaders transformed the country into one of the great military and economic powers of the world. But different perspectives need to be examined. Alternative Narratives introduces other actors, other places and other dimensions of social and political activity in an attempt to construct a broader and more complex account of modern Japanese history.

Focusing on the initial years of Japan's modern transformation, from the 1850s to the 1890s, Steele explores responses of commoners to the arrival of American warships in 1853; the growth of popular political consciousness; reactions of the residents of Edo in 1868 on the deposition of the shogun; responses of the village elite to the fall of the old regime; and established frameworks of historical narration - including American attempts to understand Japan's 1868 civil war.

The author draws upon a wealth of documents, including broadsheets, woodblock prints, political cartoons and local campaign literature, as well as more conventional material in an endeavour to find new and different ways to examine the past. This book forms an important resource to students of Japanese history and culture while simultaneously appealing to scholars interested in the general problem of history and history-writing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alternative Narratives in Modern Japanese History by M. William Steele in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

GOEMON’S NEW WORLD VIEW

The opening of Japan to Western nations in the mid-nineteenth century is a story that has been told many times and in many ways. Conventional Western accounts have long focused on the arrival of Commodore Perry’s “black ships,” four in the summer of 1853 and seven in the spring of 1854, since their appearance in Edo Bay effectively forced the Tokugawa shogun’s government to end its two-centuries-old policy of limited foreign contact. Japanese scholarship on this event, as well as most Western accounts, have tended to concentrate on the diplomatic incentives and implications of Japan’s “rude awakening.”1 These studies have drawn attention to the complexities of late Tokugawa domestic politics and shown how Perry’s “impact” led directly or indirectly to the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

But in all the mountain of research on the “black ships” there has remained a curious, but crucial, omission. We still understand surprisingly little about the reaction of the Japanese commoners, particularly those in the capital of Edo, to this series of dramatic events that so drastically changed their lives. Recent studies have begun to fill the gap, uncovering written documents that allow a glimpse into the emotions and thoughts of the men and women caught up in this crisis. Records of the shogun’s government, or bakufu, merchant account books, commoner diaries, popular songs and verses, and recorded snippets of gossip help us to understand the experience and perceptions of people confronted suddenly and rudely with a new and unknown world. But perhaps the most useful and instructive of these sources are crude woodblock prints or broadsheets known as kawaraban. Despite the relative abundance of these documents, the history of Japanese commoners during the Restoration years has yet to be written.2

My approach is to use contemporary popular art forms, particularly kawaraban, as texts that can inform their “readers” of how commoners understood the events taking place around them – events that later became the stuff of “history.” In the mid-Tokugawa period, these crude catchpenny prints, illustrated in monochrome or perhaps with two or three colors, often gave details of fires or natural disasters, or described the unusual or grotesque. As such, they were forerunners of later-day newspapers. As art, the drawings were simple and rarely the work of master craftsmen. The script often took the form of town gossip that was more interesting than accurate.

Around the beginning of the nineteenth century the prints began to comment on political events. Tokugawa authorities, concerned to keep the people ignorant of the outside world, repeatedly issued ordinances against them. Nevertheless, the prints became increasingly bold and imaginative. By the time Perry and his “black ships” arrived, kawaraban were serving both as a source of curious and sometimes useful information and as a sophisticated outlet for urban political criticism. As such, they are mines of information for the social historian seeking to clarify commoner mentalities.3

It might be argued that these prints, often the work of artist-newsmongers from the lower ranks of the samurai class, reflected the views of their makers than their townsmen readers. But the broadsheets were made to please, interest, and entertain, rather than educate and change, their readers. Printed for profit, they may well have wreaked havoc with standards of veracity and quite likely do not tell us everything we want to know of their readers’ thoughts. But the haste involved and adherence to the “Scheherazade syndrome” (if you bore me, you die) meant that kawaraban were reasonably accurate representations of important and active sectors of the mental world of the Edo commoner.

Kawaraban concerned with the “black ships” appeared in unprecedented variety and number. Goemon, a fictional Edo townsman, represents the more than 500,000 commoner residents of Edo who were both concerned and curious about the “red-haired barbarians.” Laws forbade him and his fellow townsmen from going out to view the foreigners, thereby creating a ready market for the cheap prints. Over 500 different kawaraban appeared for sale in the streets of Edo in 1853 and 1854. Since quality or artistic value was of secondary importance, each woodblock could generate up to 2,000 prints. There is evidence of many extra editions of prints in high demand. Thus, with an estimated minimum of about one million prints in circulation at affordable prices, we can reasonably assume that most of the adult population of Edo and the nearby countryside had some contact with these prints and their message.4

Kawaraban are essential texts for analyzing how the Edo townsmen reacted to the opening of their country. Kawaraban served to open the popular mind to knowledge about the West that had once been held only by the intellectual and political elite. Although often filled with inaccurate information, the woodblock prints gave the commoners their first detailed view of the world outside Japan. They helped to create Goemon’s new world view.

The “black ships” prints fall into several categories. The most numerous are depictions of the “black ships” themselves. The accuracy of some of the prints indicates direct observation; most of the prints, however, were highly imaginative, drawing on previous depictions of Dutch ships in Nagasaki. A second category deals with the attempts of the shogun and daimyo to deal with the foreigners. Numerous prints depicted problems connected with coastal defense. Some took the form of maps of Edo Bay and showed fortifications, gun batteries, and placement of troops from the various domains; others told of the negotiations between Perry and bakufu high officials. A third category of prints reveals a deep curiosity about the outside world. Crude world maps were in high demand, while other prints depicted foreign lands and peoples, their costumes, customs, and languages. Gifts presented by the Americans were especially highlighted. Prints of a miniature steam locomotive, the telegraph, and other ingredients of barbarian material culture were particularly popular. A fourth category includes prints that were decidedly anti-foreign, some of them humorous but many betraying anger and violence. A final category of kawaraban involves anti-government satire. Here the rich resources of commoner wit were put to their most difficult test.

I am especially interested with the third and fourth categories, as these prints most clearly demonstrate the creation of a new world view. Edo townsmen, I contend, reacted to the opening of Japan with nationalistic sentiments similar to those of the ruling samurai class. There is also evidence of a growing disenchantment with their superiors in light of their obvious helplessness in dealing with the foreign world. My conclusions are tentative; they are based only upon a preliminary analysis of late Tokugawa broadsheets. The potential of these documents for social historians demands a more comprehensive treatment.

Fishermen were the first commoners, or for that matter Japanese, to see Commodore Perry’s “black ships” sailing into Edo Bay. Astonished at this sudden appearance of aliens and their craft, they thought the steamships loomed “as large as mountains” and traveled “as swiftly as birds.”5 Bakufu officials immediately issued orders to mobilize local police and warned the people of the possibility of war. The great city of Edo, with a population close to one million, was swept by panic. Rumors spread as warriors sought desperately to arm themselves for battle. People bought food and supplies to stock up in the event of an emergency, causing the price of rice and other commodities to rise rapidly. A contemporary account gives a good description of the confusion brought on by this sudden encounter with the unknown:

The usually lively streets of Edo are filled with panicky commotion. People are carrying to and fro all sorts of arms and furniture. The second-hand clothing stores all hang out coats of arms and clothing necessary for soldiers. Those who make their living as smiths all busy themselves making armor, helmets, swords, and spears. Dealers in weapons pile up old arms in their shops, and sell them for doubled prices. Men and women who live near the sea coast, both samurai and commoners, have begun to evacuate with their old and young. The broad streets of the shogun’s capital are packed with people running about in panic as they carry furniture and possessions. Such a state of things breeds wild rumors and the people have no peace of mind.6

While it is possible to exaggerate the fear and confusion caused by Perry’s “black ships,” interest in the strangers and their strange lands knew no bounds. A news paper correspondent aboard one of Perry’s ships saw the Japanese as “the most curious, inquiring person, next to a Yankee, in the world.”7 Japanese people were eager to learn more about the outside world – after all, the Tokugawa bakufu had systematically limited contact with foreigners and banned books and other printed materials that dealt with foreign affairs.8 Perry and his men were hard put to answer the barrage of questions they encountered. But the samurai elite were not the only ones inquisitive. Foreigners who visited Japan in the wake of Perry’s arrival commented on the incessant stares of the crowd. Dr. James Morrow, a scientist who accompanied Perry, complained of “the curiosity of the rabble.” When he walked through a village, for example, “hundreds of the common people came out and looked at us with great curiosity.”9

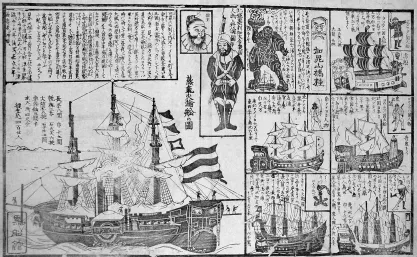

Most commoners were not fortunate enough to see the foreigners first hand. Goemon, our representative Edo townsman, and his friends were forced to satisfy their curiosity by the purchase of chapbooks and broadsheets crammed with “enlightening” information. A typical example can be seen in the print entitled “A picture of a steamship” (Figure 1.1).10

“Black ships” prints, like Figure 1.1, were numerous and appeared in many formats, usually with supplementary information about the size and crew of the ships and a short history of the countries they came from. This 1854 print shows the black ships of America and several other countries. Its description of Perry’s mission is, for the most part, accurate, although the portrait of the American “king” (top leftmost insert) is hardly flattering. The information given about the Mongols, South Americans, Europeans, English, and Russians is, however, largely imaginary and perhaps intended more for entertainment than for enlightenment. The section on Russia in the lower right-hand corner, for example, reads:

Figure 1.1 “A picture of a steamship” (Jōki karinsen no zu, 1854)

Source: Kurofune-kan

Picture of a Russian large ship. This country is to the west of Japan. The country is … a very evil country. To the north there is an island that is called the Isle of Dwarfs. About 1,000 ri to the south is the Black Man’s Country and further south is the Night People’s Country.

The drawing of the foreign ships obviously did not derive from first-hand observation. Even the American “steamship” is probably based on earlier Nagasaki prints of Dutch sailing ships, touched up with a sidewheel and smokestack. In many cases, as in Figure 1.1, the Dutch national flag flies from the American ships. The short description of America probably derived from Chinese sources, such as the Haiguo tuzhi (Kaikoku zushi) which appeared in a popular Japanese edition in 1854.

During the Tokugawa period detailed knowledge of world geography was by and large limited to the intellectual and political elite.11 The arrival of Perry’s “black ships” changed all of this. Many kawaraban took the form of world maps, such as the one shown in Figure 1.2a. Although primitive in comparison with Western maps of the same date, these were among the first representations of the worl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Goemon’s new world view

- 2 The Japanese discovery of Japan

- 3 The village elite in the Restoration drama

- 4 Everyday politics in Restoration period Japan

- 5 Edo in 1868

- 6 The United States and Japan’s civil war

- 7 The emperor’s new food

- 8 Political localism in Meiji Japan

- 9 1890: Peripheral visions

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index