![]()

A

Abe Shintarō

Son-in-law of KISHI NOBUSUKE, Abe in 1986 took over what had been the Kishi faction from FUKUDA TAKEO, and was one of four principal faction leaders in the LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY (LDP) from then until his death in 1991.

Born in Yamaguchi in 1924, he graduated from Tokyo University and became a journalist soon after the war. In 1958 he was first elected to the house of REPRESENTATIVES for a Yamaguchi constituency. His first Cabinet position was that of Agriculture Minister in the MIKI Government (1974–6). He then became Chief Cabinet Secretary in the Government of his faction leader, Fukuda, in 1977–8. He was later Minister of Trade and Industry under SUZUKI in 1981–2. In November 1982 he entered the primary elections for the LDP presidency and came third out of four candidates, with a mere 8.28 per cent of the vote. NAKASONE YASUHIRO, however, the victor in that contest, made him Foreign Minister, a post in which he remained between November 1982 and July 1986. As Foreign Minister to a Prime Minister dedicated to activism on the world stage, Abe made many international trips; he was in frequent touch with world leaders such as President Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. He also explored the implications of the emergence of the Gorbachev regime in the USSR.

He served at various times in senior party positions, including that of Secretary-General. Like other faction leaders, he was implicated in the RECRUIT SCANDAL of 1989.

At about this time he became ill with cancer and died in May 1991.

Further reading

Curtis (1988)

administrative guidance (Gyōsei shidō)

The practice of administrative guidance has been a controversial method of bureaucratic control that used to be a central method in the management of the economy. By some, it has been criticised as undemocratic interference in the sovereignty of the people’s elected representatives in Parliament. Others have seen it as one of the key instruments of the Japanese economic ‘miracle’. Foreign governments and businesses have pilloried it as an obstacle to free trade.

In fact, administrative guidance was a product of the particular circumstances of the 1960s, and has declined greatly in importance since the 1980s. From the late 1940s until the early 1960s the Japanese economy was essentially an administered economy. Government – meaning for the most part Government ministries – had at their disposal a comprehensive range of legal controls affecting much of what industry was able to do. If a firm wanted to move into a new area of manufacture, was reluctant to merge with another firm, needed foreign exchange, or could be accused of ‘dumping’ in foreign markets, it was liable to regulatory action sanctioned by law. The same went for ‘excessive competition’ in an industry, something not normally well regarded by Government officials. By the early 1960s, however, Japan was embarking on a range of liberalising measures – in part owing to international pressure – and these threatened the integrity of bureaucratic control. The MINISTRY OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND INDUSTRY (MITI, Tsūsanshō) put great pressure on politicians to pass a Special Measures Law, designed in particular to protect designated industries. This, however, failed to attain sufficient LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY (LDP) support, and was aborted in 1963. In the opinion of Chalmers Johnson it was this failure, and the fear of MITI officials that their ability to influence industrial decisions and the direction of the economy would disappear, which led to the emergence of administrative guidance as a primary instrument of policy.

The essence of administrative guidance was that it was informal and extra-legal, but that its efficacy depended on a combination of continuous networking and implied sanctions. In addition, at the time when the practice was at its height, Japanese society lacked a culture fiercely defensive of individual autonomy and rights, such as would have severely inhibited attempts to apply it in most Western countries. It is at least arguable that a culture privileging conformity over rugged independence facilitated the promotion of administrative guidance. MITI, the key ministry in this regard, used it to promote mergers and strengthen the competitiveness of new industries that needed to establish their competitiveness in the international market-place. As foreign interests frequently pointed out, bureaucratic regulation – most often informal and opaque – also conspired to minimise foreign penetration of the domestic Japanese market.

Okimoto argues that for administrative guidance to work, several conditions need to be fulfilled. The industry concerned should contain few firms and they should be used to interacting with each other. There should be a market-leader. The market should be rather concentrated. The industry should have reached a mature stage in its life cycle. There should be a strong industrial association, a history of dependence on MITI, and common problems affecting the whole industry. He points out that the newer industries of the 1980s, such as computer software, hardly at all fulfilled these conditions, though administrative guidance was still used in relation to international trade and the administered decline of sunset industries.

In the early 2000s, administrative guidance is not entirely dead. Since the early 1990s attacks on the kind of ‘regulatory state’ philosophy that it implies have become intense. It is widely felt that administrative guidance is hardly appropriate for a mature economy, and the difficulties experienced by the economy in recent years tend to be placed at the door of over-regulation and networks that are instruments of regulation. The instinct of government officials to persuade, pressure, cajole and sanction remains, but the spheres in which such actions are effective have narrowed.

Further reading

Inoguchi and Okimoto (1988)

Johnson (1982)

Okimoto (1989)

Yamamura and Yasuba (eds) (1987)

Administrative Management Agency

After earlier ad hoc arrangements, this agency was set up during the Allied Occupation in 1948 in order to provide guidance and control over the public service as a whole. It became an external agency of the prime minister’s office (Sōrifu, originally Sōrichō), with a Minister of State as its Director. It consisted of the Director’s Secretariat, an Administrative Control Bureau (Gyōsei kanrikyoku) and an Administrative Inspection Bureau (Gyōsei kansatsukyoku). Although it was not generally regarded as a major Government body, it could on occasion provide a useful political springboard for its Director. NAKASONE YASUHIRO, as its Director between 1980 and 1982, used it to organise the Second Ad Hoc Administrative Reform Commission (Dai niji Rinchō), which reported during his own period as Prime Minister from 1982.

In 1984, as a result of a recommendation of the Dai niji Rinchō, the Administrative Management Agency became the MANAGEMENT AND CO-ORDINATION AGENCY (Sōmuchō), which also inherited a few functions from elsewhere.

administrative reorganisation, January 2001

In December 1997 a report commissioned by the HASHIMOTO Government recommended a drastic reorganisation of Japanese Government ministries and agencies. This meant in particular a substantial reduction in their number through amalgamations of existing bodies. Given the extraordinary stability of the administrative structure since the Occupation period (and, in the cases of some ministries, back to the Meiji period), the reform appeared surprisingly radical.

On 6 January 2001 the number of ministries and agencies was drastically cut back, creating a number of super-ministries. The broad purposes of the reform were, first, to attack what had come to be known as ‘vertical administration’, whereby rather narrowly based administrative organs jealously protected their turf and developed projects that often overlapped with those of other organs regarded as their competitors. Amalgamation was expected to facilitate co-operative relationships within broad functional areas of the bureaucracy. Second, the reform was designed to make political control of the public service easier to implement. Third, it was expected to help create a more lean and efficient administrative culture. And a final purpose was to promote transparency and policy review – rather weak elements of the system up to that point.

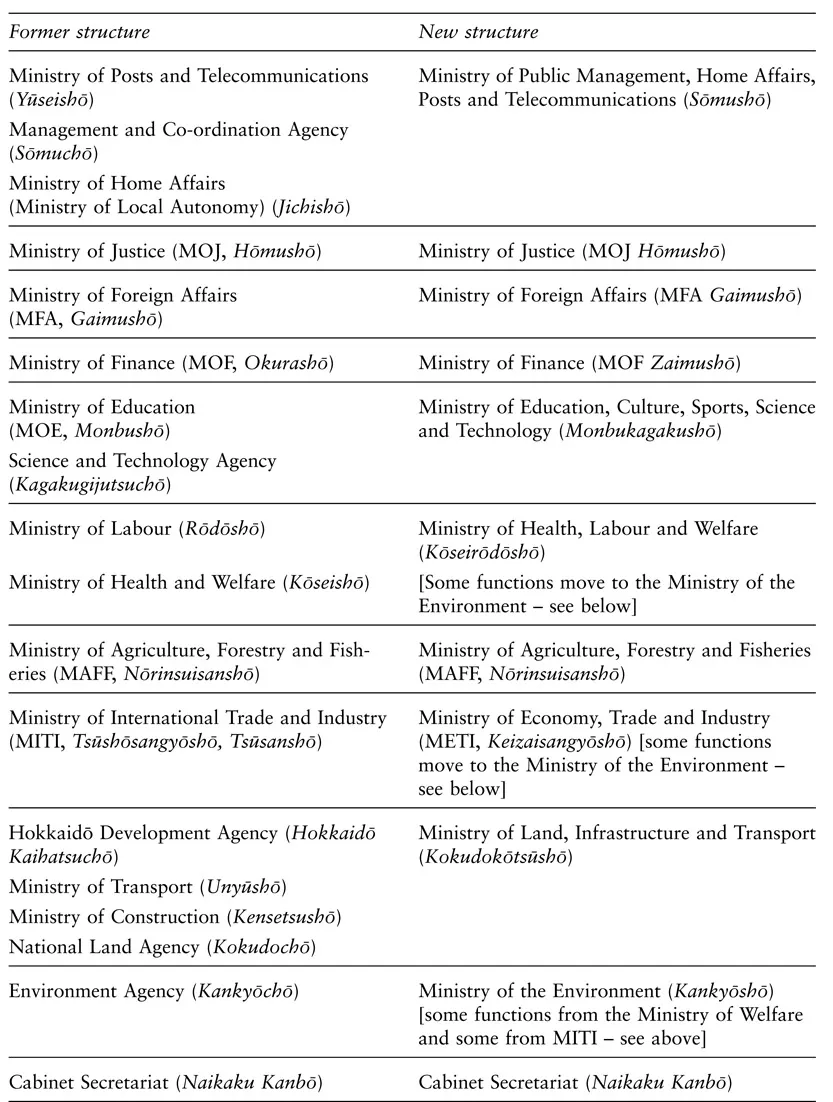

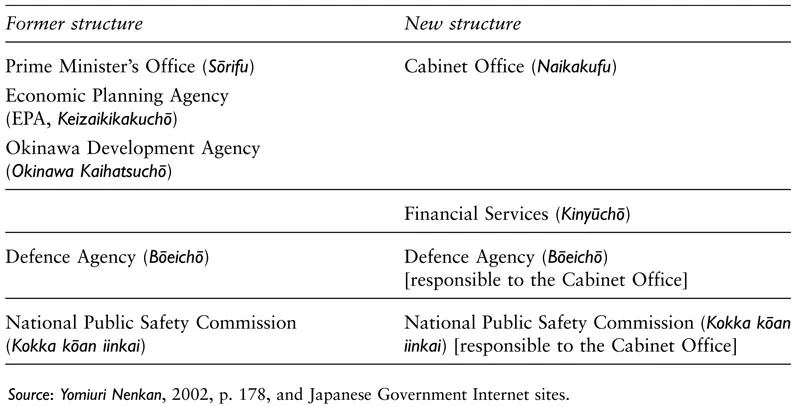

In tabular form, the changes may be portrayed as on Table 3.

Several aspects of this reorganisation are worth noting. First, three ministries survived without amalgamation or change of name. These are the MINISTRY OF JUSTICE, MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS and MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES. Second, the MINISTRY OF FINANCE suffered a change of name in Japanese (the English translation is the same) that was a psychological blow given the long history of its cherished name, Okurashō. By contrast, the ENVIRONMENT AGENCY found its status upgraded to that of ministry.

Third, amalgamation of four ministries and agencies (including the MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT and the MINISTRY OF CONSTRUCTION) into the MINISTRY OF LAND, INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORT was designed to produce a coordinated approach to all aspects of transport infrastructure. The joining of the MINISTRY OF LABOUR and the MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND WELFARE was supposed to link employment policy with welfare policy. The creation of the MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, CULTURE, SPORTS, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY produced a linkage with obvious policy implications. It was rather less obvious why MINISTRY OF POSTS AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS, the MANAGEMENT AND CO-ORDINATION AGENCY (now called Public Management) and MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (local government) should have been put together in one super-ministry.

Fourth, the creation of the CABINET OFFICE, with various administrative bodies responsible to it, was part of a broader attempt to strengthen the powers of the PRIME MINISTER. Finally, all the ministries and agencies in the new structure were under pressure to cut costs and pare down their functions, rationalising overlapping functions wherever possible.

Administrative Vice-Minister (jimu jikan)

The Administrative Vice-Minister is the most senior official in a ministry or agency of government. It is not to be confused with the Political Vice-Minister (Seimu jikan), which is a junior ministerial position filled by a politician.

Normally, the Administrative Vice-Minister is in effect chosen within the ministry from among the most senior cohort of officials. Until recent reforms that have made the system less predictable, those entering the ministry in a particular year rose by seniority at the same pace as each other, until they reached senior echelons, when opportunities narrowed, and at the very top level only one position remained, that of Administrative Vice-Minister. Typically, though not always, all other members of his cohort resign when one of them attains the top position. Some of these are then found amakudari positions. In recent years there have been some well-publicised examples of interference by the minister in top personnel appointments, including appointments to the position of Administrative Vice-Minister. This tends to cause great controversy and is intensely resented within the ministry or agency.

Koh found that over 80 per cent of those appointed Administrative Vice-Minister in the 12 ministries of the national government between 1981 and 1987 had graduated in Law, with Economics the runner-up on just over 11 per cent. Well over 80 per cent of them were

Table 3 Former and new ministries and agencies

graduates of Tokyo University, and of these an overwhelming majority were graduates of its Faculty of Law. In nearly all ministries those achieving the top position were jimukan (generalists) as distinct from gikan (technical officials). The only exception among the 12 ministries of the pre-2001 system was the MINISTRY OF CONSTRUCTION (Kensetsushō), where the position of Administrative Vice-Minister alternated between jimukan and gikan.

The Conference of Administrative Vice-Ministers (Jimu jikan kaigi) has been widely regarded as a key decision-making body of government. It consists of the jimu jikan in all ministries and agencies, as well as one or two other top officials not actually enjoying the same title. Its meetings precede those of Cabinet, and its function is to ‘pre-digest’ issues and reach decisions to be put for final decision to Cabinet itself. If this means that Cabinet meetings are often perfunctory, there is evidence that even the Jimu jikan kaigi essentially ratifies decisions that have been negotiated beforehand in nemawashi exercises between ministries and agencies, no doubt with some political input as well.

Reforms since the late 1990s designed to increase political input into decision-making has complicated, and perhaps slightly weakened, the role of the Administrative Vice-Minister and of the Jimu jikan kaigi. The ending of the practice whereby government officials could speak on behalf of ministers in Parliament, and the introduction of Deputy Ministers (Fukudaijin and Seimukan), as well as the creation of the CABINET OFFICE (Naikakufu) in January 2001, were designed to mitigate the dominance of top officials in the decision-making process. How far these reforms will have the desired effect remains to be seen.

Further reading

Johnson (1982)

Koh (1989)

Africa, relations with

Relations with Africa have never been a major part of Japan’s relations with ...