- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Recent instances of bioinvasion, such as the emergence of the zebra mussel in the American Great Lakes, generated a demand among marine biologists and ecologists for groundbreaking new references that detail how organisms colonize hard substrates, and how to prevent damaging biomass concentrations.

Marine Biofouling: Colonization Processes a

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marine Biofouling by Alexander I. Railkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Communities on Submerged Hard Bodies

1.1 ORGANISMS AND COMMUNITIES INHABITING THE SURFACES OF HARD BODIES

In seas and oceans, especially along the coasts, there are many hard bodies, both at the bottom and within the water column. One group is made up of non-living natural substrates: underwater rocks, reefs, hard ground, clastic rocks, stones, tree trunks, etc. In another group, a more active one both chemically and physically, there are living organisms: macroalgae and animals, whose surfaces are inhabited by numerous epibionts. The third group includes material constructed of metal, plastic, concrete, and wood: ships, pipelines, cables, piles, etc. They may be chemically inert or, on the contrary, aggressive, if they are protected from biofouling by toxic substances.

The underwater world of hard surfaces is rather diversified, both in its species composition and in the abundance of organisms. It includes various types of microorganisms, invertebrates, and macroalgae. It is rather heterogeneous because it is represented by communities developing on various hard substrates under different ecological conditions.

V.N.N. Marfenin (1993a) writes:

Among bottom biocenoses, the systems of hard grounds are the most variable ones. They are populated both by seston feeders, utilizing suspended particles, zoo- and phytoplankton, and by algae (within the photic zone). Among them, numerous commensals, predators, and saprophages find shelter and food. Animals from other biotopes frequently come to spawn there. And all of this exists owing to the hard ground, which creates a reliable surface for colonization, and the water movement over the substrate, which brings food to the animals (p. 131).

Coral reefs are well known hard-substrate communities (Odum, 1983; Naumov et al., 1985; Sorokin, 1993; Valiela, 1995). The calcareous foundation of the reef may go down many hundreds of meters, sometimes more than a kilometer. It consists of skeletons of dead organisms, mainly corals, sedentary reef-forming polychaetes, and coralline algae. The total area of the live coral reefs in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans is about 600,000 km2 (Sorokin, 1993). In principle, practically any region of the Tropical zone is suitable for coral life. Therefore, some experts believe that the corals could occupy an area 15 to 20 times greater (Naumov et al., 1985). Coral reefs are among the most productive areas in the world (Valiela, 1984, 1995). On the hard substrates of the reef, the biomass of zoobenthos may exceed the biomass of nearby soft grounds by one to three orders of magnitude (Sorokin, 1993). A vast number of animal and plant species inhabit the reef. The population of a single reef usually includes over a hundred species of polychaetes, crustaceans, mollusks, and echinoderms.

The plant and animal population of the benthos, plankton, and nekton may serve as a hard substrate for communities of epibionts, which are extremely widespread (Wahl, 1989, 1997; Wahl and Mark, 1999). It is difficult to find species of attached animals and plants or slow moving animals which do not carry other organisms on their surface. The specific features of communities developing on animals and macroalgae are mainly determined by the way of life and other properties of the basibiont organisms, serving as support for epibionts. Many seaweeds are little fouled or not fouled at all. Of attached animals, only sponges are little fouled, and also some corals and ascidians. All those organisms release bioactive substances that inhibit colonization and development of epibionts on them (see Chapter 10). Fast-swimming animals, such as fishes and dolphins, are also little fouled, which may be partly accounted for by the toxins contained in their mucous covers (see Pawlik, 1992).

Of practical importance are communities developing on the surfaces of industrial objects: ships, port and hydrotechnical structures, pipes, fishing nets, and other movable and stationary structures. They are rather heterogeneous. Some of them (nets, piles, moorings, etc.) have chemically inert surfaces and are subject to intensive colonization by marine organisms. Others, such as ships, are protected from fouling by toxic substances. As toxins in the paint are exhausted, the ship hull gradually gets fouled. The communities of macroorganisms developing on such surfaces have low diversity, owing to the dominance of the few macroalgal and invertebrate species most resistant to the toxic paints and life on the surface of a moving ship.

Different hard substrates, both natural and artificial, in accordance with their integral properties, can be divided into neutral, attractive, repellent, toxic, and biocidal. The peculiarities of colonization of different types of surfaces by the dispersal forms are considered in Chapters 4 to 10.

Communities developing on hard substrates on or near the bottom and in the water column, in spite of certain differences in their structure and species composition, are similar in general, because they develop in the same ecological environment, on the interface between hard surfaces and water, usually under conditions of increased water exchange as compared to communities on soft ground. The following life forms are characteristic of communities inhabiting hard substrates: sessile organisms, borers, and vagile forms (Railkin, 1998a).

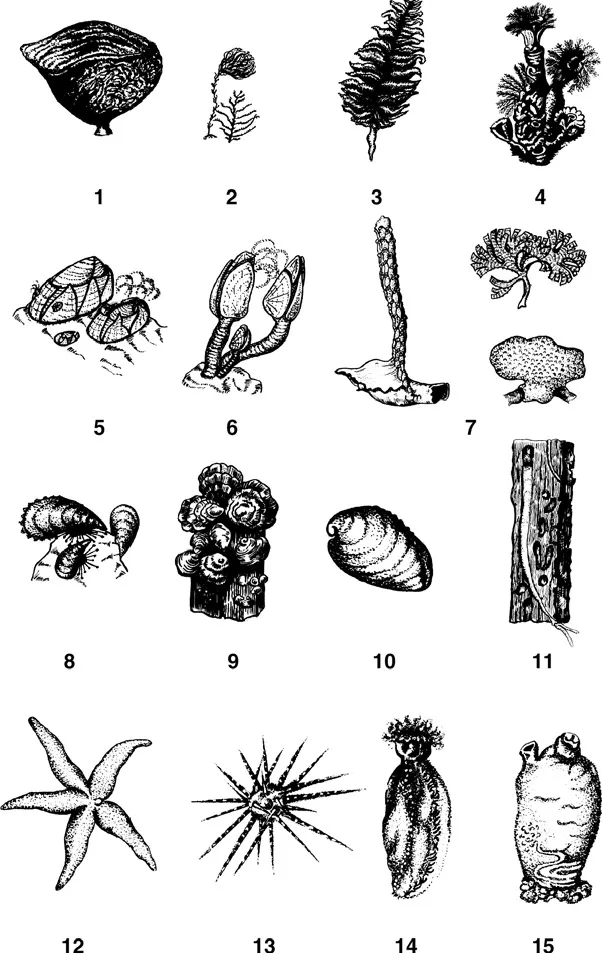

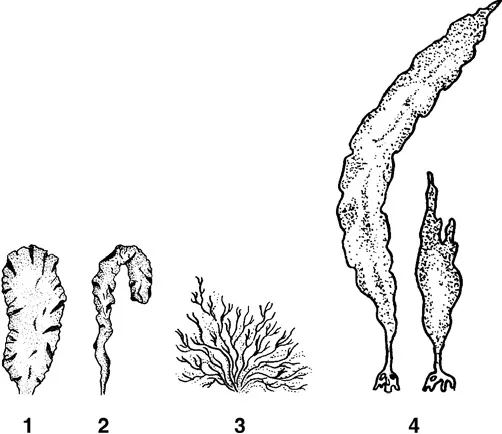

In hard-substrate communities, sessile forms usually dominate in abundance and biomass, and act as edificators, i.e., determine the community structure and its microenvironment. These include macroforms such as sponges, hydroids, corals, sessile polychaetes, barnacles, mussels, bryozoans, sea cucumbers, ascidians (Figure 1.1), and macroalgae (Figure 1.2). Microorganisms are mainly represented by sessile bacteria, diatoms, microscopic fungi, heterotrophic flagellates, sarcodines, and sessile ciliates. The sessile macroorganisms inhabiting hard surfaces, in turn, serve as a new substrate for colonization by other organisms, including sessile ones. As a result, new sessile organisms of the second, third, and higher orders are involved in the process of successive colonization of the surfaces (Seravin et al., 1985), and thus these communities acquire a characteristic multilayered vertical structure (Partaly, 1980; 2003).

FIGURE 1.1 Marine animals inhabiting surfaces of hard bodies. (1) Sponge; (2) hydroid polyps; (3) coral sea pen; (4) polychaetes of the family Serpulidae; (5–6) cirripedes: acorn barnacles Balanus (5) and goose barnacles Lepas (6); (7) bryozoans; (8–11) mollusks: mussel Mytilus (8), oyster Ostrea (9), abalone Haliotis (10), shipworm Teredo navalis and its tunnels in wood (11); (12–14) echinoderms: starfish Asterias rubens (12), sea urchin (13), sea cucumber (14); and (15) ascidian.

FIGURE 1.2 Marine macroalgae. (1–2) Green algae Ulva (1) and Enteromorpha (2); (3) red alga Ahnfeltia; (4) brown alga Laminaria.

Another life form typical of communities inhabiting hard substrates is composed of the so-called borers, among which, together with sessile animals and macroalgae, vagile animals also occur. Borers demonstrate high specialization and a close physiological and biological connection with the hard substrate (see Section 1.3). The material they inhabit serves not only as shelter for them but also as a source of food. The paradox is that gradually eating the hard substrate (wood, stone, etc.), they may finally destroy it so thoroughly as to deprive themselves of the initial shelter.

Besides the two specialized groups, hard substrates are also inhabited by such vagile invertebrates as turbellarians, nematodes, errant polychaetes, crustaceans, gastropods, echinoderms (starfish and sea urchins), and also vagile microorganisms (mainly diatoms and various protists). The complicated branching, multilayered structure of the community formed by sessile macroorganisms reduces the hydrodynamic action upon vagile forms and serves as a kind of protection for nonattached species. Macroalgae, settling on the hard surface, form a kind of canopy over it, which creates an additional substrate and also shelter for vagile organisms living on and under it. Thus, among sessile organisms, vagile crustaceans, worms, mollusks, and also echinoderms find their abode. It is also highly probable that vagile organisms inhabiting hard substrates, including hard grounds, may possess mechanisms of increased adhesion to the surface on which they move, since even at the bottom, they usually live under the condition of augmented hydrodynamic activity. If they did not possess such mechanisms, they would be easily washed away from the surface.

Sessile, boring, and vagile forms inhabiting hard bodies are characterized by their position on the surface, fast adherence, and typically by being attached to the surface. In marine and fresh waters, the communities inhabiting hard substrates of different nature and origin are represented by similar life forms and may be considered as a single ecological group (Railkin, 1998a). Within its limits, according to the substrate criterion, smaller groups can be distinguished: communities of epibenthos, inhabiting non-living substrates, such as submerged rocks, stones, hard ground, etc. (Savilov, 1961; Khailov et al., 1992; Oshurkov, 1993); communities of epibionts inhabiting the surfaces of underwater animals and plants, sessile and vagile (Wahl, 1989, 1997); fouling communities on man-made structures (Costlow and Tipper, 1984), and some others.

Of course, not all communities possess all the characteristics described above. Any scheme, including the one above, is idealized to some extent. Thus, the multilayer structure of communities does not attain proper development. Yet such major characteristics as the dominance of sessile species, their edifying role in communities, and finally their surface position on the substrate, are always present.

Relegating of the hard-ground populations to the communities of hard substrates needs further comments. Let us seek them in the detailed study performed by A.I. Savilov (1961). In the Sea of Okhotsk, he distinguished zones of prevalent development of different ecological groups. Among them, the fauna of hard grounds (rocky, gravelly, sandy, and dense sandy-silt ones) is considerably developed in terms of its abundance and biomass. It is characterized by the prevalence of immotile seston feeders, represented by numerous species of sponges, hydroids, soft corals, gorgonarians, cirripedes, some bivalves, brachiopods, bryozoans, and ascidians, i.e., the same groups (Figure 1.1) that inhabit hard substrates beyond the bottom. Communities of hard ground are subject to faster flows than those occurring on soft ground. Similar descriptions of communities inhabiting hard ground are to be found in the works of other authors (e.g., Osman, 1977; Sebens, 1985a, b; Protasov, 1994; Paine, 1994; Osman and Whitlatch, 1998).

In spite of a near 100-year history of studying hard substrates (Seligo, 1905; Zernov, 1914; Hentschel, 1916, 1921, 1923; Duplakoff, 1925; Karsinkin, 1925), there is still disagreement concerning the terms used to represent the communities of microorganisms (Cook, 1956; Sládečková, 1962; Gorbenko, 1977; Weitzel, 1979; and others) and macroorganisms (Tarasov, 1961a, b; Konstantinov, 1979; Braiko, 1985; Iserentant, 1987; Wahl, 1989, 1997; Railkin, 1998a; etc.) inhabiting them. For example, a number of authors (Reznichenko et al., 1976; Braiko, 1985; Hüttinger, 1988; Zvyagintsev and Ivin, 1992; Tkhung, 1994; Clare, 1996; Zvyagintsev, 1999, and others) consider that fouling communities represent a special assemblage of organisms on artificial substrates and man-made structures rather than on natural objects. Other authors (e.g., Mileikovsky, 1972; Zevina, 1994; Grishankov, 1995; Walters et al., 1996; Targett, 1997; Railkin, 1998a; Rittschof, 2000) regard fouling as the process of colonization of any substrate, including natural (living and non-living) ones, and also as the result of this process — the communities formed on various hard substrates.

A.A. Protasov (1982, 1994) analyzed over 350 sources from the 1920s to the early 1980s and found 21 terms for designating those communities. Six of them appeared the most widely used: Aufwuchs (Seligo, 1915), Bewuchs (Hentschel, 1916), periphyton (Behning, 1924), fouling (Visscher, 1928), and two Russian terms obrastanie and perifiton, translated into English as fouling and periphyton, respectively. These terms were used in 89% of the cases and other terms were employed in 11%.

In view of the common features of communities inhabiting hard substrates in the aquatic medium, considered above, it is possible to unite them into one ecological group. Following the historical tradition of assigning Greek names with the ending -on to large ecological groups of water organisms (plankton, nekton, neuston, pleuston), communities on hard substrates can truly be called periphyton, from the Greek περιφυ´ω (περι , meaning around and φυ´ω, meaning to grow, i.e., to overgrow). This term was first suggested by Behning (1924, 1929), though in a more narrow sense, to designate fouling of objects introduced into water by man. To designate communities inhabiting hard substrates, I will mainly use the term hard-substrate communities. Development of such communities will be referred to as biofouling or simply fouling, and the organisms forming them as foulers.

Unlike organisms inhabiting the surfaces of hard substrates, the typical inhabitants of soft grounds are vagile or sedentary organisms that live mainly within the ground and rarely on its surface. It should be noted that the soft grounds include the sediments (clay, silt, or fine sand) with particles below 1 mm in size. Four life forms of the inhabitants of soft grounds can be distinguished (Zernov, 1949): (1) vagile forms inhabiting the surface, not infrequently partly submerged into the ground (for example, echinoderms, crustaceans); (2) small vagile forms living between ground particles; (3) large vagile burrowing forms; and (4) sedentary forms.

It should be emphasized that sedentary or slow-moving invertebrates inhabiting the soft bottom do not get attached to its particles but are only anchored in it or on it. Therefore they are not attached to the substrate as are the typical inhabitants of hard substrates. A stronger connection with the soft ground is achieved by different means: due to the flattening of the body (e.g., many mollusks, starfishes, some urchins, encrusting bryozoans, calcareous algae), the thickening of the skeleton (a number of polychaetes, brachiopods, mollusks, echinoderms, etc.), forming tubes out of ground particles (polychaetes). Sedentary organisms not infrequently develop special rootlike outgrowths to hold themselves in sand and silt, which they do not possess when they inhabit a hard surface. This can be observed in a number of sponges, soft corals, polychaetes, bryozoans, and ascidians (Savilov, 1961; Zenkevich, 1977; Railkin and Dysina, 1997). In some cases such appendages may be considerably developed. When typical inhabitants of hard grounds colonize soft ones, they usually first get attached to some hard substrate: fragments of shells, mollusks, shelters of other invertebrates, small stones, pebbles, etc. (Savilov, 1961; Zenkevich, 1977). Usually these substrates are not to be seen from the surface of the soft ground since they gradually sink into the ground together with the organisms inhabiting them. Many invertebrates inhabiting soft ground live under conditions different from those characteristic of the hard substrates. This can be accounted for by the fact that many species live within the ground. Even species constantly existing on the surface of the soft ground live, as a rule, under the condition of poor water exchange which occurs in the near-bottom layer. Soft grounds are inhabited by organisms adapted to life in narrow spaces and able to move within the ground. They are oxygen deficient and have little if any light (Burkovsky, 1992; Valiela, 1995). Marine benthic grounds are also characterized by a low pH and reduction-oxidation potential (eH) values. Specific microorganism activity sometimes results in accumulation of a great quantity of hydrogen sulfide, leading to the phenomenon known as “kill”. The toxic effect of sulfides is based on oxygen radicals (see Section 10.5) being formed from reactions with sulfides (Tapley et al., 2003).

All the above allows us to distinguish the communities inhabiting soft ground as a single ecological group, which may be called emphyton, from the Greek εμϕυ´ω (εμ, meaning in, inside and ϕυ´ω , meaning to grow) (Railkin, 1998a).

The same species of macro- and microorganisms may be members of communities inhabiting soft ground and hard substrates, including hard ground (e.g., Savilov, 1961; Oshurkov, 1993). During reproduction periods, they release propagules into the plankton. These propagules can settle on hard...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface to the American Edition

- Author

- 1 Communities on Submerged Hard Bodies

- 2 Biofouling as a Process

- 3 Temporary Planktonic Existence

- 4 Settlement of Larvae

- 5 Induction and Stimulation of Settlement by a Hard Surface

- 6 Attachment, Development, and Growth

- 7 Fundamentals of the Quantitative Theory of Colonization

- 8 General Regularities of Biofouling

- 9 Protection of Man-Made Structures against Biofouling

- 10 Ecologically Safe Protection from Biofouling

- 11 The General Model of Protection against Biofouling

- 12 Conclusion

- References