eBook - ePub

Preventing Medication Errors and Improving Drug Therapy Outcomes

A Management Systems Approach

- 434 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Preventing Medication Errors and Improving Drug Therapy Outcomes

A Management Systems Approach

About this book

Read this book in order to learn:

Why medicines often fail to produce the desired result and how such failures can be avoided

How to think about drug product safety and effectiveness

How the main participants in a medications use system can improve outcomes and how professional and personal values, attitudes, and ethical reasoning fit into

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Preventing Medication Errors and Improving Drug Therapy Outcomes by Charles D. Hepler,Richard Segal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Prestazione di assistenza sanitaria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Second Drug Problem

How is it possible that modern medicine still does not provide care of known benefit sufficiently and correctly? Quite simply, deficiencies in medical quality are due to inadequacies of organization, delivery, and financing systems.Bernard Bloom

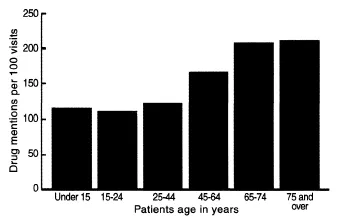

Drug therapy may be the most common modality of therapy in the industrialized world. In the United States, just under two thirds of all physician office visits include one or more prescriptions. The frequency of prescription use increases slightly with age (Figure 1.1).1 Doctors and patients intend drug therapy to improve the quality of peoples’ lives, by curing or controlling disease. However, this is too often not the outcome of drug therapy. Research data show that preventable injury and death from drug therapy are major public health problems in most industrialized nations. Their costs, both human and financial, are major burdens on everyone. The billions of dollars that are spent to correct preventable drug-related morbidity (PDRM) could be used to prevent it, thereby gaining not only better quality of care but also reduced costs and improved access.

Adverse effects of drug therapy may be the fourth leading cause of death in the United States, according to a literature review in the Journal of the American Medical Association.2 Lazarou et al. estimated that in 1994 there were from 76,000 to 137,000 deaths from adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in U.S. hospitals. Even with the lower estimate, ADRs would be the sixth leading cause of death. This ranks mortality rates from ADRs among those caused by heart disease, cancer, stroke, and accidents. A recent report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reviewed the prevalence and significance of human error in health care and its implication for patient safety. The report found that medication-related errors are “one of the most common types of errors… substantial numbers of individuals are affected, and it accounts for a sizeable increase in health care costs.”3

Chapter 2 will show that the prevalence of preventable hospital admissions caused by drug therapy rivals those from myocardial infarctions, cancer, diabetes mellitus, and asthma. Comparisons to diabetes and asthma are ironic, by the way, because drug therapy is such an important part of their management, and we know that mismanagement of drug therapy is a cause of hospital admission for patients with those diseases.

The money spent to correct preventable office visits, emergency department visits, hospital days, etc., may approximate $100 to $300 annually for each man, woman, and child in the United States. The news media now refers to the intentional abuse of drugs as “the drug problem.” Preventable drug-related morbidity is then the industrialized world’s “second drug problem.” It lags drug abuse in popular coverage but may well cause more human misery and waste more money than drug abuse. Clearly, we should prevent adverse outcomes of drug therapy from a clinical and humanitarian viewpoint. Moreover, by preventing them, we may make health care much more efficient.

FIGURE 1.1

Number of prescriptions (mentions) per 100 physician office visits in the United States in the year 2000 (National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey).

Stories about real people add human meaning to the statistics. When we consider the tragedy of Katherine’s death (see Preface) in the context of research, we see that it is not a rare occurrence. There are many more stories of avoidable injury and death from mismanaged drug therapy. They shock and offend, and make many people seek simple explanations and quick solutions. Katherine LaStima’s death is shocking and offensive, but is actually one of the less dramatic and more commonplace examples. Her story is rather a tragic symbol of how ordinary this problem really may be in community health care.

The death of Katherine is a symbol of a pervasive and major public health problem—adverse outcomes from the mismanagement of routine drug therapy. Although people die of asthma, nearly all asthma deaths are preventable.4,5 If Katherine had been murdered or killed by a drunk driver, we would be outraged. We should be even more outraged by a death due to inadequate medical care. The mismanagement that killed Katherine LaStima exemplifies many important points found in research literature, but perhaps most of all, her death illustrates the banality of evil and the wisdom of Edmund Burke’s admonition, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

Two reports from the IOM on the quality of medical care in America produced a flurry of activity recently and some continuing effort to correct the problem.3,6 But still, there is no consensus to improve the overall system of medication use.

Preventing PDRM should be directed at root causes. The sheer number of potentially significant root causes, however, suggests that preventing PDRM by separate, specific remedies might be impossibly complicated, especially considering the thousands of drug products available. Furthermore, few studies show that changing one element in medications use affects outcomes. Theoretically, reengineering the medications use system could address many root causes for many drugs, providers, and patients. This has in fact been confirmed by several studies that improved outcomes and reduced total costs, as described in Chapter 8.

Dramatic improvements in patient outcomes are possible when physicians, patients, and pharmacists cooperate in systematically managing outcomes. This promising research has been accumulating for nearly 20 years, yet somehow it has not yet been followed up by many health care professionals and researchers, and continues to be ignored by many new mandarins of managed care. Meanwhile, literally thousands of lives and millions of dollars are wasted by PDRM. So, there are two problems: the basic problem of PDRM, and the secondary problem that society has been so slow to respond to the primary problem.

This situation should provoke strong motives to do whatever is needed to make drug therapy safer and more effective. Health professionals and managers in North America and Europe are among the best educated in the world. Given the significance of the problem, their response has been absurdly inadequate. A preventable disease is endemic to most or all of the industrialized world. Its prevalence and cost rank with major diseases like diabetes and heart disease. We have some evidence about how to prevent or at least ameliorate this disease, but we do very little with it. This is surely not the way the world of health care is supposed to work.

Most citizens of the United States, Canada, U.K., and other countries known to have high prevalence of PDRM seem to take great pride in the quality of their medical care, but seem to accept such failure. Many are shocked by the facts. We could not have the PDRM problem some people say. It must be confined to subpopulations like the elderly, poor, or teaching hospital patients or rural backwaters. Furthermore, people have faith in their doctors and pharmacists. If we had the PDRM problem, would not the doctors, pharmacists, and hospitals know about it and fix it? The short answer is no.

Why Do These Problems Persist?

These problems exist, and persist, because the technology of drug therapy has far outstripped society’s traditional ways of thinking about it and customary arrangements to control it. The United States and many other Western societies have demanded that marketed drug products be safe and effective. Then, in effect, they have sent those safe and effective drug products into an unsafe and ineffective system of use.

In the days of tinctures and fluid extracts (roughly until the 1940s), the list of effective drug products was shorter and, the rate of pharmaceutical innovation was slower than today. Professionals and patients had time to develop experience with drugs. Concerns involved drug purity, potency, and consistency. The pharmacist’s job was to obtain high-quality crude drugs and to prepare them properly. A pharmacy smelled like, and in many ways was, an apothecary shop. One-way communications from physician to pharmacist through a prescription were sufficient.

Making drug products has now been taken over mainly by the pharmaceutical industry. This has led to many new drug products, safer and more effective. Drugs, dosage forms, and their potency are now standardized. Most nations closely regulate the pharmaceutical industry. Manufacturers have to prove the safety, effectiveness, purity, potency, and consistency of drug products.

Drug products make billions of dollars for their manufacturers. Consequently, they are articles of commerce as much as professional instruments of care. The industry has become a powerful force. It advertises directly to consumers. It contributes to political campaigns and funds research. Only the naive would believe that the industry does not influence the interpretation of research results.7

Consumers and purchasers, especially third-party payers like insurance companies, are keenly aware of drug products as expensive articles of commerce. Total expenditures for drugs are rising rapidly. Higher prices and higher total expenditures for drug products are a real worry, but they must not be allowed to draw attention away from how well those expensive medicines are used. The proper use of medications can lower total costs of care, and misuse can increase it by more than the cost of the drugs themselves.

The list of drug products numbers into the thousands, and innovation (real or apparent) is rapid. The complexities of dosages, drug interactions, and allergies are mind-boggling. Nonetheless, the family physician is expected to manage therapeutics single-handedly. Communication to the pharmacist is still mostly one-way, through a prescription, although the biggest questions now may concern the effect that the prescription is having on the patient. Community pharmacists, freed from drug preparation, have become part of a commercial distribution system.

In short, reality today is quite different from when drug controls were set up. Traditional thinking about drug therapy, however, has outlived the galenical era. The concepts and language that stakeholders* use to talk about drug therapy, adverse effects, and treatment failures may be the basic problems. How we think about medications use surely determines how speak about it and what we do about it.

The medications use system is poorly understood. The conventional wisdom about how to provide safe, effective, and efficient drug therapy sometimes lacks a basis in fact, and is therefore often wrong. For example, unsafe drug products and inappropriate prescribing are not the leading cause of patient injury in ambulatory care, and sometimes have nothing to do with causing injury. Yet managed care organizations spend more money to influence prescribing than on any other aspect of medications use.

Like many others, Katherine LaStima did not die of an adverse drug reaction, toxicity, or side effect. Despite being in the care of a specialist, she died of the natural course of her disease, asthma. She died in part from exposure to an overload of allergens at the county fair and in part because her doctor, pharmacist, parents, and even Katherine herself did not control her drug therapy, and therefore did not control her asthma.

Overuse of albuterol, an asthma “rescue” medicine, is rarely harmful and did not kill (or even directly harm) Katherine. Frequent inhaler use, however, is a useful marker to show that asthma is slipping out of control. The extra albuterol helped Katherine to breathe while her disease was getting worse. Also, she was using too little “preventer” medicine (a steroid-like cortisone) that fights the cause of asthma symptoms. In effect, Katherine was fighting her symptoms instead of her disease. When she went to the fair, she may have been extremely vulnerable to the allergens that she encountered there.

Many people seem to focus on the drug product instead of the manner of its use. Perhaps some patients and providers value convenience and reassurance more than competent care and a disciplined, full understanding of how to use medicines. The effects of the preventer medication would not have been apparent to them, so perhaps Katherine and her parents did not fully understand that it was essential.

We have to change the normal arrangements of community practice. These arrangements do not permit enough coordinated attention to drug therapy. In particular, interprofessional cooperation is usually inadequate. A patient, physician, or pharmacist cannot manage drug therapy alone. Katherine’s pharmacist obviously emphasized his function as a dispenser of medicines rather than his potential role as a cotherapist in the management of Katherine’s asthma.

When something goes wrong and a patient is injured, the tendency is to look for simple solutions: the drug product itself or the people involved. While professional errors cause some heart-wrenching injuries, very few patient injuries are caused by errors, at least as most people would understand the term. In this instance, the physician and pharmacist were sued.

People like Katherine are not supposed to die of asthma, so it would have seemed that somebody must have made a mistake, for example, the doctor or pharmacist who treated Katherine. She had been repeatedly hospitalized in the past, and her pattern of medication use just before she died showed that she probably was beginning another exacerbation. Court records show that Dr. Michael and the pharmacist, Mr. Merchant, knew the possible adverse consequences of her medication use pattern. They said that they had warned her mother, Joanne, more than once. Her death could have been prevented by any of the participants in her care, even by Katherine herself.

The point is not to exculpate the doctor or pharmacist. Of course people should be held accountable when they fail to meet their responsibilities. Accountability, with or without punishment, seems just and may provide some measure of meaning and closure to a tragic event. Nevertheless, there are two problems with the approach of blame and liability. The first is that apportioning blame among all the participants in drug therapy, given their rights to defend themselves, can be cumbersome and expensive at best. Since blame is retro-spective, the second problem is that blame seldom leads to preventative measures. Risk management may emphasize money rather than causes.

Long court battles are likely, one case at a time. Some, perhaps most, will be settled with no finding of blame and with confidential agreements. Possibly, professionals can be sanctioned by their regulatory boards. Neither outcome is likely to reduce the risk of the next tragedy. No penalty that a court could have imposed on Dr. Michael, Mr. Merchant, or the LaStimas would have reduced the likelihood of another patient being injured by inadequate management. Such tragedies are repeated again and again by different people.

Perhaps more importantly, changing our view from blame toward prevention would allow us to think about this problem more productively. More sophisticated, professional practice standards in Massachusetts might have prevented her death. Hale Hospital should have known the significance of Katherine’s prior admissions for asthma. A computer at the insurance company could have flagged her inappropriate prescription refill patterns. The mass media could have done a better job of informing the public about the dangers of medications use. None was to blame. Outside the structure of error and blame, however, each of them could have contributed to a safer system of medication use. (As it happened, the insurance company that paid for Katherine’s albuterol might have objected to her overuse, had it known about it. Mr. Merchant concealed the timing of some refills so that the LaStimas would not have to pay for them out of pocket. But the insurance company did not object to Katherine’s underuse of preventer medication, which probably contributed as much to her death as her overuse of albuterol.)

Instead of apportioning blame through litigation, our legal system could have interpreted Katherine’s long-standing misuse of medications as demonstrating systems’ failure. Perhaps failure of a single component or participant could have been detected and corrected before her final asthma attack.

We must question the basic arrangements for providing therapy.

Most Western medical systems tacitly hold that the doctor will be responsible for “everything,” but...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- The Authors

- 1: The Second Drug Problem

- 2: Morbidity and Mortality from Medication Use

- 3: Understanding Adverse Drug Therapy Outcomes

- 4: People and Purpose in Medication Use

- 5: Access, Cost, and Quality Issues in Medication Use

- 6: Prescribing and Prescribing Influence

- 7: Medications Use System Performance Information

- 8: Outline of a Medications Use System

- 9: Effect of Pharmaceutical Care Systems on Outcomes and Costs

- 10: A Pharmaceutical Care System

- 11: Medications Management System

- 12: Managed Care

- 13: Managed Care Strategies to Influence the Cost, Access, and Quality of Medicines Use

- 14: A Market Perspective

- 15: Finding a Way Toward Medications Use Systems

- Glossary