- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nutrition and Health

About this book

Nutrition and Health is an easy-to-read introduction to the role of the human diet in maintaining a healthy body and preventing disease. Wiseman provides a concise overview of all important aspects of diet and health including: * definitions of food types* energy requirements, exercise, obesity and eating disorders* nutrition in pregnancy, children

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nutrition and Health by Gerald Wiseman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nutrition, Dietics & Bariatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Energy

All the energy needed for growth and repair of the body, for muscular activity of all kinds and for all the work done by cells comes from the metabolism of carbohydrate, fat, protein and alcohol. The numerous other items of the diet, even though essential for other reasons, do not provide energy, although many are directly involved in the chemical reactions which yield energy. If the diet is adequate and properly balanced the energy normally comes chiefly from carbohydrate and fat, while most of the protein is used for cell growth and repair. When there is not enough carbohydrate and fat, the protein is used for energy and is then not available for other purposes. As dietary protein is generally less abundant than carbohydrate and fat, and usually more expensive, using protein for energy is comparatively wasteful. In some communities, however, there may be plentiful protein and it may then be eaten in sufficient quantity to be used for both cell building and for energy.

The intake of food is governed in health by the appetite which under ordinary conditions controls the weight of the body with remarkable precision. Many people taking only moderate care are able to keep their weight more or less unchanged over several decades. If they take food in excess by only a small amount, that excess energy can be disposed of as heat and thereby prevent fat accumulation. This seems to work very efficiently in some people. It is, however, easy to over-ride the natural controlling mechanism and consume substantially more energy than is required. When this happens the excess energy is stored in the body as fat.

During ageing there is a fall in the weight of the bones, due to loss of minerals, plus a fall in the weight of the muscles, hence if the total body weight remains constant there must be compensatory changes, mainly an increase in the body fat.

The ability of the body to override the mechanism which controls energy intake has survival value when the supply of food is unpredictable because it enables fat to be accumulated when there is plenty of food and its energy to be used later when food is scarce. How long a healthy adult can survive without food depends to a large extent on the fat stored: with adequate water, people have lived for many weeks. When people die during starvation they often still have some fat in their body. They die because during starvation body protein is metabolised as well as body fat and it is the loss of the protein that is usually die cause of death. The control of body weight is dealt with in Chapter 2.

Nutritional status

Body mass index (BMI)=

Weight (kg) ÷ Height (m)2

The nutritional status of most people can be assessed sufficiently well by their appearance, body weight and by simple questions about general health. For a more critical assessment their body mass index can be determined. This gives a weight for height ratio and is a good guide to underweight or overweight in adults except for those who are extremely muscular or have excessive accumulations of water in the body. The use of the body mass index is described in Chapter 2 on obesity.

If weighing is not possible, an assessment can be made by measuring the circumference of the upper arm with a tape-measure. A point midway between the shoulder and the elbow is used with the arm at rest, preferably hanging down. This simple measurement reflects the size of the underlying muscles and the subcutaneous fat, as well as the bone and the skin. In undernourished persons and in those overweight it will be the muscles and the fat which will change in bulk rather than the other tissues. For adult men on a satisfactory diet the circumference ranges from about 250–320 mm and for women from about 220–300 mm.

In children chronic energy lack causes a low height for age ratio, especially if the parents and siblings are of average height or more.

Energy content of food

1 g fat = 9 kcal (38 kjoule)

1 g carbohydrate = 4 kcal (17 kjoule)

1 g protein = 4 kcal (17 kjoule)

1 g alcohol = 7 kcal (29 kjoule)

When carbohydrate, fat and alcohol are metabolised for energy in the body they are normally converted completely to carbon dioxide and water, with energy being released during the process. Protein metabolism during energy release yields various nitrogen containing substances in addition to carbon dioxide and water. By mimicking these reactions in laboratory experiments the energy value of any food can be measured and expressed as kilocalories (kcal) or kilojoules (kjoule) per gram of the food. One kcal is equal to 4.18 kjoule. The energy values for carbohydrate, fat and protein are approximately 4 kcal (17 kjoule) per gram for carbohydrate and protein and 9 kcal (38 kjoule) per gram for fat. For alcohol, the value is 7 kcal (29 kjoule) per gram. Hence if the amounts of carbohydrate, fat, protein and alcohol in a meal are known, the energy value of the meal can be calculated easily.

Table 1 Energy provided by common foods

Some foods are energy-rich because they contain little or no water, fibre or other material which does not yield energy; examples are metabolizable sugars, fats and oils. Foods with much water and dietary fibre are usually energy-poor. For example, 100 g table sugar (sucrose) will provide 400 kcal, whereas 100 g of items such as lettuce, tomatoes or cucumber, which contain about 95 per cent water plus fibre, will provide only about 20 kcal. Eating most salad items instead of sugar, fats and oils greatly reduces the energy intake.

The energy values of some everyday foods are shown in Table 1. Natural foods vary in composition from sample to sample and the values given in tables are average ones. This is especially so for animal products in which the fat content may be very variable.

The amount of carbohydrate, protein and fat in the diet varies greatly but an average national picture in 1983 showed that about 12 per cent of the daily calories came from protein, about 46 per cent from carbohydrate and about 42 per cent from fat. From then until 1996 the protein intake was more or less constant, the carbohydrate fell by a few percent, while the fat eaten rose slightly, despite repeated advice that the fat content of the average diet was excessive. A much healthier intake would be about 12 per cent of calories from protein, about 58 per cent from carbohydrate and only 30 per cent from fat. Many children become habituated to eating high-fat foods and as adults they dislike changing their habits. The food industry does not produce on a mass scale a sufficient variety of attractive low-fat foods, particularly snacks.

Energy expenditure

Part of the energy produced by the body may be used for the production of extra tissue during growth or tissue repair and this energy does not appear as heat. It is locked in the new tissue and although it can be estimated it is often ignored. In contrast, the rest of the metabolic energy, which in adults is virtually all of it, does appear as heat and can be measured accurately in specialized laboratories. The technique is called direct calorimetry. Because this requires special expensive apparatus and is very time consuming, the energy produced by the body can also be calculated from the amount of oxygen taken up and the carbon dioxide given off in the breath. This method, called indirect calorimetry, is easy, cheap and relatively quick. These basic experiments on energy production were first carried out at the end of the nineteenth century and since then many measurements have been made of the energy produced by adults and children while resting or engaged in all sorts of activities. Knowing how much energy is produced each day tells us how much energy needs to be eaten, which enables suitable diets to be designed for all occasions.

The results of these investigations show that almost all normal adults need about 500 kcal for the usual eight hours of sleep. The energy needed for eight hours of work and for eight hours of non-work, however, varies considerably, as would be expected. People who do sedentary work requiring little physical activity need about 2200 kcal per 24 hours, those who do moderately active work need about 2500 kcal per 24 hours, while the few who undertake heavy work require 3000–3500 kcal per 24 hours. Moderately light housework needs only about 2000 kcal per 24 hours but this goes up if there are young children to care for, when the amount of physical activity may be greatly increased.

A person expending about 2200 kcal per 24 hours gives off as much heat as does a lit 100 watt electric light bulb. The skin is not as hot as the bulb because the body has a much larger surface area for heat loss, but in both cases the total heat being lost is about the same.

The values given here and elsewhere for the energy expended during different activities are only guidelines and may vary greatly from subject to subject and often in the same subject doing the same thing at different times.

Effect of body weight

The energy requirement of overweight people is usually less than that of thin people of similar age. This is partly because in the overweight the thicker layer of fat under the skin reduces the body’s heat loss, so that less heat production is needed to keep the body temperature normal, requiring less food to be metabolised. In addition, overweight people tend to be less active and therefore need to produce less energy. However, when overweight people are active, the extra weight they carry needs extra energy and their food requirement may go up very markedly.

Effect of age

During the process of ageing the energy requirement gradually decreases. In part this is because in older people some muscle, which is metabolically very active, is often replaced by fat. The ageing process is also accompanied by a fall in the hormones which normally keep the metabolic rate high. Between the ages of about 20 years and 80 years the resting energy requirement falls by an average of about 15 per cent. The total energy requirement of older people may also decrease because many become less mobile, although some do remain remarkably active and may need a higher food intake than some much younger people. The energy intake on ageing needs to be reduced to match any fall in energy expenditure to prevent the familiar gaining of weight with the passage of years, mostly accepted as inevitable, though it does not need to be so.

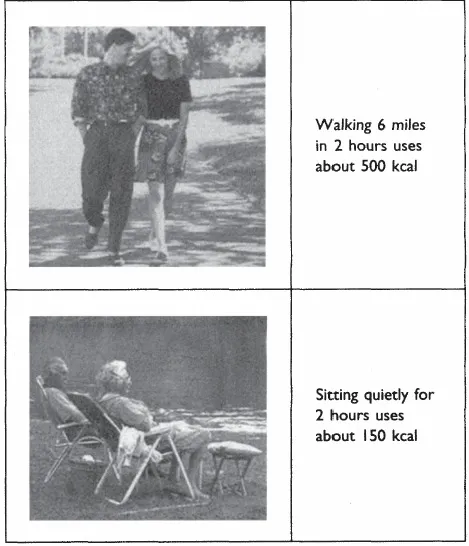

Effect of exercise

The amount of energy used during exercise is closely related to movement. Frequently moving the body greatly increases the energy used, especially if the body is lifted rather than merely moved horizontally. For using up energy and thereby using up body fat, most forms of exercise are not very good. For example, walking six miles on the level in two hours would be considered an energetic pursuit for many adults yet it uses up only about 500 kcal, which is about 350 kcal more than simply sitting quietly. Three slices of bread with butter supply about 350 kcal. If all the extra 350 kcal used during this exercise came from the body fat the weight of this lost fat would be about 40 g, representing about 50 g of the adipose tissue which stores the fat. If this six mile walk were undertaken every day for a week, the loss of body weight might be about 350 g (about three-quarters of a pound). Most people will find this a not very impressive result. It may seem much better to eat three slices of bread with butter less each day! Regular exercise is nevertheless very desirable for general fitness.

Effect of undernutrition

When food is plentiful the energy expended is replenished by eating. This is controlled by the appetite. Under these conditions it is easy to expend more energy if necessary. When food is scarce, however, and energy intake limited, physical activity is reduced to more or less match the reduced energy intake. Under very severe conditions the physical activity may fall so much that even necessary tasks may be abandoned and survival thereby threatened. It is clearly not useful to ask starving people to work harder, nor somebody dieting on a very low calorie intake to do more exercise.

After a period of severe undernutrition the body may accumulate water (oedema), making body weight an inadequate guide to the degree of wasting. When such a starving person is given a good diet the accumulated fluid is excreted in the urine causing a fall in body weight, which may alarm the subject who, unless warned, expects to gain weight as soon as extra food is eaten.

Effect of pregnancy and lactation

This is described in Chapter 3.

Table 1 Energy provided by common foods

| Very high (More than 500 kcal/100 g edible portion) | Almonds, Brazil nuts, butter, chocolate, fats, hazelnuts, oils, peanuts, walnuts |

| High (250–500 kcal/100 g edible portion) | Beef (medium fat), cheese, cornflakes, dates (dried), herring, honey, lamb, mackerel, raisins, rice |

| Medium (50–250 kcal/100 g edible portion) | Avocado, bananas, beans, beef (lean), bread, chicken (no skin), cod, duck (no skin), egg, figs (dried), haddock, ham (lean), heart, kidney, lentils, liver, maize, milk, peas, pork (lean), potatoes, prawns, prunes, rabbit, salmon, tongue, turkey (no skin), veal |

| Low (Less than 50 kcal/100 g edible portion) | Apples, apricots (fresh), broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrots, cauliflower, celery, grapefruit, lettuce, mushrooms, oranges, pears, plums, spinach, sweet peppers, tomatoes, watercress |

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Tables

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Energy

- Chapter 2: Obesity and weight control

- Chapter 3: Pregnancy and lactation

- Chapter 4: Infancy (0–1 year of age)

- Chapter 5: Young children (1–6 years)

- Chapter 6: Adolescents (10–20 years)

- Chapter 7: Ageing

- Chapter 8: Illness

- Chapter 9: Anorexia nervosa and bulimia

- Chapter 10: Vegetarianism and veganism

- Chapter 11: Diet selection

- Chapter 12: How to interpret food labels

- Chapter 13: Food additives

- Chapter 14: Food allergy and food intolerance

- Chapter 15: Food toxicity

- Chapter 16: Avoiding food-borne illness

- Chapter 17: Exercise

- Chapter 18: Protein

- Chapter 19: Carbohydrate

- Chapter 20: Fat

- Chapter 21: Alcohol

- Chapter 22: Water

- Chapter 23: Dietary fibre

- Chapter 24: Beverages

- Chapter 25: Cholesterol

- Chapter 26: Vitamins: general

- Chapter 27: Vitamin A

- Chapter 28: Vitamin B1

- Chapter 29: Vitamin B2

- Chapter 30: Vitamin B6

- Chapter 31: Vitamin B12

- Chapter 32: Vitamin C

- Chapter 33: Vitamin D

- Chapter 34: Vitamin E

- Chapter 35: Vitamin K

- Chapter 36: Folate

- Chapter 37: Niacin

- Chapter 38: Pantothenic acid and biotin

- Chapter 39: Calcium, osteoporosis and phosphate

- Chapter 40: Iron

- Chapter 41: Sodium, potassium and chloride

- Chapter 42: Iodine

- Chapter 43: Fluoride

- Chapter 44: Selenium

- Chapter 45: Zinc

- Chapter 46: Copper and molybdenum

- Chapter 47: Magnesium

- Chapter 48: Aluminium, cadmium, cobalt, germanium, manganese, nickel, silicon, strontium, sulphur and tin