eBook - ePub

Riparian Areas of the Southwestern United States

Hydrology, Ecology, and Management

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Riparian Areas of the Southwestern United States

Hydrology, Ecology, and Management

About this book

Riparian Areas of the Southwestern United States: Hydrology, Ecology, and Management provides hydrologists, watershed managers, land-use planners, educators, policymakers, and non-governmental organizations with a comprehensive account of the multiple benefits and conflicts arising from the uniquely structured ecosystems of arid and semi-arid regions. The text describes the inhabitants of southwestern riparian ecosystems and addresses the research, planning, and management concerns for these fragile ecosystems in relation to the impacts of water and sediment flows, livestock grazing, and other human activities, and the maintenance of key wildlife and fish habitats.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Riparian Areas of the Southwestern United States by Peter F. Ffolliott,Leonard F. DeBano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1: Introduction

Peter F. Ffolliott, Malchus B. Baker, Jr., Leonard F. DeBano and Daniel G. Neary

CONTENTS

1.1 Hydrologic Relationships

1.2 Ecological Relationships

1.3 Resource Use

1.4 Changing Emphasis of Riparian Management

1.5 Summary

References

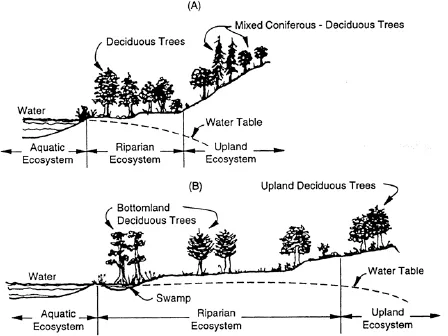

Riparian areas, situated in the interfaces between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, are located along the banks of rivers and perennial, intermittent and ephemeral streams and around the edges of lakes, ponds, springs, bogs and meadows. Riparian corridors are largely delineated by soil characteristics and by vegetative communities that require free or unbound water. The abruptness and extent of transitions between the terrestrial and aquatic interfaces that delineate the riparian areas are generally site specific. Transitions across terrestrial, riparian and aquatic ecosystems in the southwestern United States tend to be more abrupt than those in the more humid eastern United States (Figure 1.1).

Riparian areas occupy less than 2% of the total land area in the Southwest. However, these ecosystems are often the most productive and valuable of all of these lands. They are found in a wide range of climatic, hydrologic and ecological environments, from high-elevation montane forests through intermediate-elevation woodlands to low-elevation shrublands and desert grasslands (see Plate 1 in color insert following page 174). Major river drainages and tributaries supporting riparian ecosystems include the lower Colorado River from Lee’s Ferry in northern Arizona to the Gulf of Mexico; the Rio Grande River from Colorado through New Mexico and Texas to the Gulf of Mexico; the Gila, Salt, Verde and San Pedro Rivers in Arizona and the Pecos River in southwestern Texas. Communities are established along stream channels where surface or near-surface water is available much of the year. These channels contain perennial, intermittent and ephemeral streams. Other riparian areas and associated wetlands occur at high elevations and other mesic areas are found near reservoirs, stock tanks and other water-storage structures at all elevations.3

Figure 1.1 Transition profiles across terrestrial, riparian and aquatic ecosystems in (A) the southwestern United States (adapted from Johnson, R.R. and Lowe, C.H., On the development of riparian ecology, in Riparian Ecosystems and Their Management: Reconciling Conflicting Uses, Tech. Coords. Johnson, R.R. et al., USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins CO, 1985) and (B) the eastern United States (adapted from Clark, J.R. and Benforado, J., Introduction, in Wetlands of Bottom Hardwood Forests, Clark J.R. and Benforado, J., Eds., Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co., Amsterdam, 1981.)

1.1 HYDROLOGIC RELATIONSHIPS

Vegetation, physiography and geologic formations within a closely linked system control the flow of water and movement of sediments and other pollutants through riparian corridors. Most stream systems originating in the low elevations are intermittent or ephemeral. Flowing water occurs mostly during the winter and spring after large frontal storms and infrequently during the summer after convectional storms.4,5 Although streamflow is often discontinuous at low elevations, communities of riparian vegetation can occupy adjacent floodplains where the water table is near the surface most of the year. Annual precipitation at high elevations generally is sufficient to sustain longer periods of streamflow and, in some cases, maintain a perennial flow. A more reliable source of water in these areas is available for the growth and survival of riparian plant communities.

The health of riparian corridors in terms of the efficiency of hydrologic and ecological functioning is largely dependent on the storage and movement of sediments through the channel system. Transport of sediments into and through riparian corridors is largely episodic, because the primary mover of eroded soil materials is the large, infrequent storm.6,7 The intermittent storage and subsequent movement of sediments through the channel systems in response to a disturbance are complex processes. An important disturbance factor is the loss of plant cover associated with improper or excessive management practices or with a severe wildfire, where large volumes of surface runoff and streamflow transport sediment deposits that were previously stored in the channel system.

Channel dynamics within riparian corridors are generally related to the movement of water and sediments from the surrounding hillslopes into the channel systems. Human-induced and natural disturbances such as flooding, wildfire, road construction, livestock grazing or tree cutting can cause excessive sediment movement. Sediments in intermittent or ephemeral streams are deposited within the channel until a sufficiently large streamflow event moves the sediments downstream. Sediments can be stored in a channel for many years, making interpretation of the sediment-generating processes in the streams difficult.6,8 Although suspended sediments are usually the largest part of the total sediment load moved in a stream channel, the bedload component is also important in determining channel structure and dynamics.

Overland flow and the movement of sediments and other pollutants from surrounding hillslopes are key factors affecting the stability of downstream riparian ecosystems.4,6 The sediments transported in overland flow are deposited in the stream channel. The sediments move downstream in flowing water, where they can accumulate until being flushed farther downstream by larger flows. The hydrologic linkages among a watershed, its riparian corridor and larger river basins are important concepts to appreciate when managing riparian ecosystems.

1.2 ECOLOGICAL RELATIONSHIPS

Riparian corridors are delineated by soil characteristics and by vegetative communities that require free or unbound water. These corridors represent sites where soil moisture remains high. The excess water facilitates establishment of soil-vegetation habitats reflecting the influence of the extra soil moisture.7 Ecological characteristics of these habitats are the differentiating criteria that help to characterize riparian areas.

Soils at high elevations consist of consolidated or unconsolidated alluvial sediments derived from a wide range of granitic, metamorphic and sedimentary bedrock materials forming the surrounding uplands. Soils on floodplains are recent depositions, tend to be uniform within horizontal strata and exhibit little development. The alluvial soils of all riparian ecosystems are subject to frequent flooding and are characterized by a range of textures. Riparian ecosystems are in widely different geomorphologic environments that vary from narrow, deep, steep-walled canyon bottoms to somewhat exposed sites with one or more terraces or benches to wide, exposed areas with meandering streams.

Riparian vegetation occurs in relatively narrow bands along steep and narrow stream systems, while broad floodplains generally support larger areas of vegetation.9–11 Riparian vegetation often occurs as mosaics of dynamic successional stages regardless of the stream width or gradient. Many trees and shrubs require periodic flooding to disperse their seeds and create sediment bars for their germination.12–14 Therefore, the distribution and structure of stands of these trees are determined largely by flooding. In areas of frequent flooding, a recently established sediment bar can be colonized first by herbaceous plants, then by willow (Salix spp.) or cottonwood (Populus spp.) and, finally, by late-succession species such as boxelder (Acer negundo), walnut (Juglans major) or mesquite (Prosopis spp.).15

Plant composition in riparian areas is also determined by elevation. Elevational stratification is attributed to water availability for plant establishment and growth. Precipitation and snowmelt provide a source of water that is more reliable at high elevations than at low elevations, where local rainfall alone is insufficient. Riparian plants at the low elevations require access to flowing water or a groundwater aquifer.

The root systems of riparian trees and shrubs help to bind the soil together, provide streambank stability and promote high infiltration rates. A variety of grasses and grass-like plants, forbs and half-shrubs also help in armoring streambanks against large channel-forming flood flows. Trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants in riparian corridors can trap sediments and build up a soil body that often leads to the creation of floodplains (Figure 1.2).

1.3 RESOURCE USE

Livestock grazing began in the 1600s, when the Spanish established missions primarily along perennial streams, with their livestock concentrated along the streams for shade, forage and water. Riparian corridors continue to be grazed by livestock today, although the practice has been severely curtailed because of recent management unease. Managers and the public are increasingly concerned about the need to balance livestock grazing with other uses of riparian areas, which are often nonconsumptive.15–17 As a result of past overgrazing, many riparian ecosystems have deteriorated to the extent of having ceased to function in a sustainable manner, and the need for restoration is common.

Early settlers cleared large expanses of trees in floodplains so the rich alluvial soils could be placed into production for agricultural and livestock grazing purposes. People did not consider the trees in riparian forests and woodlands to be a valuable resource to sustain.7,18–20 Riparian trees were removed rather than managed, and this practice continued intermittently into the early 1970s. Recent environmental concern has greatly limited the harvest of riparian trees for wood purposes; only dead and downed wood is used for campfires in riparian areas.

Figure 1.2 Riparian trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants provide streambank stability. Headwaters of the Black River, Salt-Verde River Basin, Arizona. Photo by Malchus B. Baker, Jr., USDA Forest Service.

Food, cover and water are essential for a variety of terrestrial wildlife species that inhabit the lush vegetation and flowing water of these relatively cool and shaded streamside environments. Of all of the vertebrates in Arizona and New Mexico, 80% spend at least one half of their lives in riparian corridors; more than half of these species are totally dependent on riparian corridors.16 Many of these species are classified as threatened or endangered on federal or state listings. The greatest diversity and largest populations of birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles are found in riparian corridors compared with surrounding watersheds.

Many fish species in the perennial rivers and streams also are classified as threatened, endangered or are being considered for listing. Judicious implementation of instream flow rights is necessary to provide adequate streamflow for maintaining viable fish populations21,22 and for focusing on fishery management. Instream flow is a legal right for the nonconsumptive use of surface water within a specified reach of a stream channel for fish, wildlife, recreational use and the sustainability of st...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editors

- Contributors

- List of Color Plates

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Definitions and Classifications

- Chapter 3: Setting and History

- Chapter 4: Hydrology and Impacts of Disturbances on Hydrologic Function

- Chapter 5: Linkages Between Riparian Corridors and Surrounding Watersheds

- Chapter 6: Human Alterations of Riparian Ecosystems

- Chapter 7: Riparian Flora

- Chapter 8: Mammals, Avifauna and Herpetofauna

- Chapter 9: Native and Introduced Fishes: Their Status, Threats and Conservation

- Chapter 10: Insects and Other Invertebrates: Ecological Roles and Indicators of Riparian and Stream Health

- Chapter 11: Livestock Grazing in Riparian Areas: Environmental Impacts, Management Practices and Management Implications

- Chapter 12: Wildlife Population and Habitat Management Practices

- Chapter 13: Fish Habitats: Conservation and Management Implications

- Chapter 14: Water Availability and Recreational Opportunities

- Chapter 15: Riparian Ecosystem Assessments

- Chapter 16: Restoration of Riparian Ecosystems

- Chapter 17: Institutional Limitations to Management and Use of Riparian Resources

- Chapter 18: Future Themes and Recommendations