- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ozone Reaction Kinetics for Water and Wastewater Systems

About this book

Interest in ozonation for drinking water and wastewater treatment has soared in recent years due to ozone's potency as a disinfectant, and the increasing need to control disinfection byproducts that arise from the chlorination of water and wastewater.

Ozone Reaction Kinetics for Water and Wastewater Systems is a comprehensive reference that

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ozone Reaction Kinetics for Water and Wastewater Systems by Fernando J. Beltran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Environmental Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

In the late 1970s, the discovery of trihalomethanes (THM) in drinking water due to chlorination of natural substances present in the raw water1,2 gave rise to two different research lines: the identification of the structures of these natural substances (i.e., humic substances) and the formation of organochlorine compounds from their chlorination. 3,4 The search began for alternative oxidant-disinfectants that could play the role of chlorine without generating the problem of trihalomethane formation.5,6 This latter research line led to numerous studies on the use of ozone in drinking water treatment and the study of the kinetics of ozonation reactions in water. This research line is still productive. Recent surveys7,8 have shown that organohalogen compounds formed in the treatment of surface waters with chlorine and other chlorine-derived oxidant-disinfectants (i.e., chloramines) yield a greater number of disinfection byproducts than ozone. However, chlorine is not the only factor affecting water contamination. Other compounds are often discharged in natural waters or in soils and then migrate to underground water. The result is contamination of wells, aquifers, etc. The literature reports underground contamination from compounds such as volatile aromatics including benzene, toluene, xylenes (BTX); methyltertbutylether (MTBE); and volatile organochlorinated compounds.9–12 Ozonation or advanced oxidation processes (AOP) or hydroxyl radical oxidant–based processes, among others, have proven to be efficient technologies for the removal of these types of pollutants from water.13–16

The application of ozone is not exclusive to the treatment of drinking water. Ozone also has numerous applications for the treatment of wastewater. Here, chlorine is mainly used for disinfection purposes, leading to many problems in the aquatic environment where treated wastewater is released.17 Thus, organochlorine compounds generated from wastewater chlorination can harm aquatic organisms in receiving waters. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established a limit of less than 11 μg/L for total residual chlorine in fresh water,18 which is usually surpassed when chlorinated wastewater is discharged.19 Thus, wastewater treatment plant operators must often balance two contradictory aspects: the use of chlorine for wastewater disinfection and the preservation of aquatic life. Thus, alternative oxidant-disinfectant agents are needed for wastewater treatment. As shown in Chapter 6, ozone has been used in the treatment of a variety of wastewater. It should be highlighted, however, that ozone, like other oxidants, also produces byproducts such as bromate (in water containing bromide), which can be harmful.20 The EPA promulgated the Stage 1 Disinfectants/Disinfection By-Products (D/DBP) Rule to regulate the MCL of bromate (10 μg/L), chlorite (1 mg/L), THMs (80 μg/L), and haloacetic acids (10 μg/L).21 This rule took effect on January 1, 2002 but the EPA plans to reexamine the bromate MCL in its 6-year review process.22 So, when using ozone in the treatment of water some care must be taken to eliminate or reduce DBPs as much as possible.

Contrary to what might be assumed from this history, the use of ozone in the treatment of drinking water was not new when THMs were discovered in chlorinated drinking water. In fact, ozone started to be used, mainly as a disinfectant, in the late 19th century in many water treatment plants in Europe.23 The fact that chlorine was the main oxidant-disinfectant agent was due, among other reasons, to both extensive studies on its use during World War I for chemical weapons and its low cost.

Today, however, there are numerous water treatment plants, mainly for drinking water, that include some ozonation step in their treatment lines. In addition, interest in the kinetics of these processes has been growing because of the dual practical–academic aspects. Since ozonation of compounds in water is a gas–liquid heterogeneous reaction, the process is of great academic interest because it is one of the few practical cases outside the chemical industry in which different chemical reaction engineering concepts (mass transfer, chemical kinetics, reactor design, etc.) apply.

Data on ozonation and related processes (i.e., advanced oxidation processes) are also of practical interest for addressing the design of ozone reactors or contact times to achieve a given reduction in water pollution, improvement of wastewater biodegradability during conventional biological oxidation, or increased settling rate in sedimentation.

Ozone applications in the treatment of water and wastewater can be grouped into three categories: disinfectants or biocides, classical oxidants to remove organic pollutants, and pre- or posttreatment agents to aid in other unit operations (coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation, biological oxidation, carbon adsorption, etc.).24–28

1.1 OZONE IN NATURE

In 1785, the odor released from the electric discharges of storms led Van Mauren, a Dutch chemist, to suspect the presence of a new compound. In 1840, Christian Schonbein finally discovered ozone although its chemical structure as a triatomic oxygen molecule was not confirmed until 1872,23 and in 1952 it was established as a hydride resonance structure.29

Ozone is formed naturally in the upper zones of the atmosphere (about 25 km above sea level and a few kilometers wide) where it surrounds the Earth and protects the surface of the planet from UV-B and UV-C radiation. The spontaneous generation of ozone is due to the combination of bimolecular and atomic oxygen, a reaction that starts to develop from approximately 70 km high above sea level down to about 20 km from the Earth's surface where unfavorable conditions are established. In the atmosphere close to the Earth's surface, however, ozone is a toxic compound with a maximum contaminant level of 0.1 ppm for an exposure of at least 8 h.30 From the positive point of view, the properties of ozone, derived from its reactivity, have been applied in the treatment of water in medicine, organic chemical synthesis, etc.

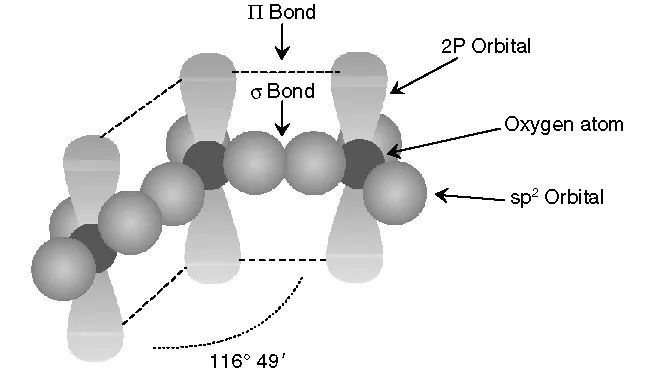

FIGURE 1.1 The molecular structure of ozone.

1.2 THE OZONE MOLECULE

Ozone reactivity is due to the structure of the molecule. The ozone molecule consists of three oxygen atoms. Each oxygen atom has the following electronic configuration surrounding the nucleus: 1s2 2s2 2px2 2py1 2pz1, i.e., in its valence band it has two xyz unpaired electrons, each one occupying one 2p orbital. In order to combine three oxygen atoms and yield the ozone molecule, the central oxygen rearranges in a plane sp2 hybridation from the 2s and two 2p atomic orbitals of the valence band. With this rearrangement the three new sp2 hybrid orbitals form an equilateral triangle with an oxygen nucleus in its center, i.e., with an angle of 120º between the orbitals. However, in the ozone molecule this angle is 116º 49".29 The other 2p orbital of the valence band stays perpendicular to the sp2 plane, as Figure 1.1 shows, with two coupled electrons. Two of the sp2 orbitals from the central oxygen, forming the angle indicated above, combine with one 2p orbital (each containing one electron) of the other two adjacent oxygen atoms in the ozone molecule, while the third sp2 orbital has a couple of nonshared electrons. Finally, the third 2p orbital of each adjacent atomic oxygen, which has only one electron, combines with the remaining 2p2 orbital of the central oxygen to yield two 9 molecular orbitals that move throughout the ozone molecule. As a consequence, the ozone molecule represents a hybrid formed by the four possible structures shown in Figure 1.2. The length of the bond between oxygen atoms in the ozone molecule has been found experimentally to be 1.278 Å, which is an intermediate value between the length of an oxygen double bond (1.21 Å) and that of a simple oxygen–hydrogen bond in the hydrogen peroxide molecule (1.47 Å). According to the literature29 the calculated lengths show a 50% likelihood that the bond between oxygen atoms in the ozone molecule is a double bond. Therefore, the resonance structures I and II in Figure 1.2 basically represent the electronic structure of ozone. Nonetheless, resonance forms III and IV also contribute to some extent to the ozone molecule because the ozone angle is l...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PREFACE

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- NOMENCLATURE

- 1: INTRODUCTION

- 2: REACTIONS OF OZONE IN WATER

- 3: KINETICS OF THE DIRECT OZONE REACTIONS

- 4: FUNDAMENTALS OF GAS–LIQUID REACTION KINETICS

- 5: KINETIC REGIMES IN DIRECT OZONATION REACTIONS

- 6: KINETICS OF THE OZONATION OF WASTEWATERS

- 7: KINETICS OF INDIRECT REACTIONS OF OZONE IN WATER

- 8: KINETICS OF THE OZONE/HYDROGEN PEROXIDE SYSTEM

- 9: KINETICS OF THE OZONE–UV RADIATION SYSTEM

- 10: HETEROGENEOUS CATALYTIC OZONATION

- 11: KINETIC MODELING OF OZONE PROCESSES

- APPENDICES