- 568 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pharmaceutical Perspectives of Nucleic Acid-Based Therapy

About this book

Emphasizing its uses in cancer and cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases, Pharmaceutical Perspectives of Nucleic Acid-Based Therapy presents a comprehensive account of gene therapy, from development in the laboratory to clinical applications. Internationally acclaimed scientists discuss the potential use of lipids, peptides and polymers for the in

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pharmaceutical Perspectives of Nucleic Acid-Based Therapy by Ram I. Mahato,Sung Wan Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Farmacología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Basic components of gene expression plasmids

Jun-ichi Miyazaki

INTRODUCTION

Various plasmid vectors, including expression units for mammalian cells, have been developed for various purposes: to produce valuable proteins, to characterize gene products, to analyze the physiological consequences of overexpressing foreign genes, or to isolate genes of interest by screening recipient cells. Recently, plasmid vectors have also been used for nonviral gene therapy, owing to the development of novel gene delivery methods, such as naked DNA injection, in vivo electroporation, and lipofection. Various modifications have been added to optimize the preexisting plasmid vectors for such in vivo use, although the basic structure of the expression plasmid vectors remains unchanged. In this chapter, an overview of the essential elements of expression plasmid vectors from the viewpoint of their in vivo use will be given.

ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF EXPRESSION PLASMID VECTORS

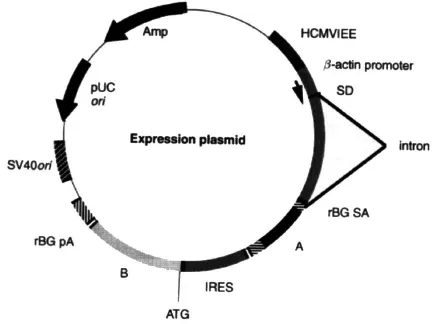

In general, expression plasmid vectors are based on prokaryotic episomal plasmids, which are combined with eukaryotic gene transcription elements (Figure 1.1). Plasmid vectors always contain an origin of replication (ori) and a selection marker. These constituents are required for the selection and amplification of plasmidcontaining bacterial cells, usually Escherichia coli. The selection marker is commonly a gene that confers resistance to some antibiotic, such as ampicillin, kanamycin, or tetracycline; of these, the ampicillin resistance gene is the most widely used. The eukaryotic part contains a single or multiple expression unit consisting of a transcriptional initiation element (enhancer/promoter), a multiple cloning site (MCS), and a sequence allowing for transcription termination. In most cases, the DNA inserted into the MCS for expression is not a genomic gene from the original exon/intron configuration, but a cDNA lacking introns. However, most expression plasmids contain an intron with splice consensus sequences 5′ or 3′ from the multiple cloning site. Apart from these basic elements, some expression plasmids contain additional elements that facilitate replication in mammalian cells. Expression plasmids for in vitro use may include a separate expression unit that confers resistance to selectable markers, permitting the isolation of stable transfectants.

Figure 1.1 The basic constituents of an expression plasmid vector. The promoter and poly (A) addition site are the transcriptional control sequences supplied by the vector. A multiple cloning site for the insertion of the gene of interest is located in the empty vector between the transcriptional control elements. The intron may be located at 3′ or preferably 5′ from the cloning site. The expression plasmid shown in this figure contains the CMV-IE enhancer, the chicken β - actin promoter, and a hybrid intron, the 5′ portion of a β -actin sequence and the 3′ portion of a β -globin sequence. This vector produces a bicistronic mRNA. In this case, the A coding sequence, placed in the 5′ portion of a bicistronic transcript, is translated in a cap-dependent manner, while the B coding sequence, placed downstream of the IRES, is translated in a cap-independent manner. Additional elements, e.g. to improve transcription, are integrated between the bacterial elements (resistance gene, origin of replication) and the basic transcriptional control elements. The abbreviations used in this figure are: HCMVIEE, human cytomegalovirus immedi ate early enhancer; SD, splice donor; rBG, rabbit β-globin, SA, splice acceptor; pA, poly(A) signal; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; ori, origin of replication.

TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATORY ELEMENTS

In eukaryotic cells, a gene consists of the transcribed portion, as well as the 5′ and 3′ flanking regulatory DNA sequences. Transcription initiation is usually regulated by the 5′ regulatory sequences, which include some common DNA elements. One of these elements, the TATA box (TATAAA), is located 25–35 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site for RNA polymerase II, and its function is to direct the transcription at the so-called cap site (Breathnach and Chambon, 1981). The CAAT box (GGCCAATCT) is known to be present upstream of the TATA box. Transcription is initiated by an interaction between these DNA elements and regulatory proteins.

Another important element is the enhancer sequence. This element was first identified in the SV40 and retrovirus genomes. Many cellular enhancer sequences have since been identified. The enhancers positively regulate transcription from the closest promoter and can act over several thousand base pairs in either orientation. They are usually found proximal to the promoter regions of genes, but are sometimes found within introns or even downstream of the transcribed region. They determine the strength, cell-type specificity, and developmental-stage specificity of the promoter. Enhancers can elevate transcription levels from several-fold to more than 1000-fold. Some enhancers are active in a wide variety of cell types, but others are active only in restricted cell types or at particular developmental stages. For example, the immunoglobulin gene enhancer is very active exclusively in B lymphocytes. The human cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early (IE) gene enhancer is extremely active in a wide range of cell types, although it shows some tissue preference (Boshart et al., 1985).

Generally the rate of transcription initiation is the rate-limiting step in mRNA production, because the rate of transcriptional elongation is usually constant, except for some genes in which premature termination or pausing is seen. Therefore, the selection of an appropriate enhancer and promoter is crucial in the construction of expression plasmid vectors. In most experiments, both in vitro and in vivo, expression plasmids driven by a ubiquitously active enhancer and promoter are very useful. Examples of such promoters include the SV40 early promoter, RSV LTR promoter, CMV-IE promoter, β-actin promoter (Miyazaki et al., 1989), and elongation factor-1 promoter α(Mizushima and Nagata, 1990). The CMV-IE promoter has been shown to exhibit very high transcriptional activity in most tissues and cell types (Foecking and Hofstetter, 1986). However, when incorpor-ated into retroviral vectors, which integrate into chromosomal DNA, the CMV-IE promoter is down-regulated, hampering long-term expression in vivo (Challita and Kohn, 1994). Furthermore, attenuation of the activity of the CMV and other viral promoters by cytokines, such as interferons (IFN-γ,IFN-β) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), has been documented (Qin et al., 1997). In contrast, attenuation of the activity of a cellular promoter (e.g., β-actin promoter) by cytokines has not been observed.

Heterologous enhancers can be combined with the promoter elements to achieve a desired expression level, or to increase expression. For example, the CMV-IE enhancer has been combined with the chicken β-actin promoter. As β-actin is the most abundant protein in most somatic cells, the β-actin promoter shows a broad expression pattern, independent of tissue or developmental stage (Miyazaki et al., 1989). The CMV-IE enhancer is very active in a wide variety of cell lines. With the hope of combining the advantages of both the β-actin promoter and the CMV-IE enhancer, a composite promoter, designated the CAG promoter, was engineered by connecting the CMV-IE enhancer sequence to a modified chicken β-actin promoter (Niwa et al., 1991). The strength of the resulting promoter was evaluated by a reporter assay after transient transfection into a number of cell lines derived from different cell types. This promoter showed higher transcriptional activity in the cell lines tested than did the CMV-IE promoter, chicken β-actin promoter, RSV-LTR, or SV40 early promoter.

The tissue specificity of an enhancer/promoter can best be characterized by making transgenic mice expressing a transgene under it. It may seem a reasonable assumption that ubiquitous promoters can direct a broad specificity of expression when used in transgenic mice. However, this is not usually the case. For example, the RSV LTR promoter is very active in a variety of cell lines, but shows a rather restricted pattern of gene expression when used in transgenic mice. On the other hand, the CAG promoter shows ubiquitously high activity in transgenic mice (Kawamoto et al., 2000).

Table 1.1 Structures of selected expression plasmidsa

CHROMOSOMAL ELEMENTS

Two other known factors that affect gene expression are the locus control region (LCR), and scaffold-associated region (SAR). However, when integrated into an expression plasmid, these elements do not affect the levels of expression in transiently transfected cells. Expression levels are affected only after the stable integration into the chromosomes, probably because these elements work specifically in the chromosomal context (Stief et al., 1989; Klehr et al., 1991). In fact, the LCR has been shown to confer copy number-dependent, position-independent, and tissue-specific expression of a transgene when integrated with the transgene, in a transgenic mouse study (Greaves et al., 1989). However, it has been suggested that sequences associated with an origin of replication may increase nuclear retention, possibly by anchoring the plasmid to the nuclear matrix.

Another element, called the insulator, was identified as a chromosomal element that blocks the effects of an enhancer on the neighboring promoter when inserted between them (Muller, 2000). The insulator was also reported to protect some stably transfected genes from epigenetic silencing. The activity of the insulator is believed to be associated with the organization of a specialized chromatin structure. Insulator sequences have been found in the K14 gene, the chicken β-globin gene and others. This element may be used to disrupt the interference between two expression units that have been incorporated into a single plasmid or between an expression unit and viral enhancers in a viral vector (Inoue et al., 1999; Steinwaerder and Lieber, 2000).

RNA PROCESSING

The conversion of the primary transcripts (heterogeneous nuclear RNA) to functional mRNA involves capping, splicing, polyadenylation (see below), and transport to the cytoplasm. These steps also strongly influence gene expression. Splicing refers to the elimination of intervening RNA sequences (introns) and requires consensus nucleotide sequences at the splice donor site, the splice acceptor site, and the branch point (Sharp, 1987). The exon/intron boundaries, as well as the sequences required for the correct recognition of these boundaries are conserved, and primary transcripts from heterologous species in the animal kingdom are usually recognized and processed in mammalian cells.

Most eukaryotic genes contain introns, although some intronless genes are known. When introduced into mammalian cells, some genes have been shown to depend on the presence of an intron for their efficient expression (Buchman and Berg, 1988; Ryu and Mertz, 1989; Yu et al., 1991). Interestingly, the requirement for the presence of introns seems even stronger for DNA constructs introduced into transgenic mice (Brinster et al., 1988). The construct in which the rat growth hormone gene is driven by the mouse metallothionein I promoter requires an intronic sequence for efficient expression in transgenic mice, but not for expression in stably transfected cultured cell lines. In this experiment, it was shown that introns from heterologous genes are about as effective for enhancing gene expression as endogenous introns. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the dependency of genes on introns for efficient mRNA formation is not known, it is still recommended to include at least one intron in expression vectors. However, the use of introns can create artifacts resulting from aberrant splicing.

The SV40 small t-intron is one of the most commonly used introns in expression vectors and is also one of the shortest introns to produce a lariat branch site complex. During expression from vectors in which the SV40 small t-intron is present in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR), splice donor sites from the preceding cDNA genes may sometimes be preferentially used. Splicing from these sites to the splice acceptor site of the S V40 small t-intron may result in a deletion of mRNA within the protein coding region (Nordstrom and Westhafer, 1986). Splice donor sites in the cDNA could exist as a consequence of splice junctions from former introns. Furthermore, ordinarily inactive splice consensus sequences (cryptic splice donor or acceptor sites) are found in both the introns and exons of many genes. These may be utilized together with introns from expression vector sequences. Thus, introns should not be located in the 3′ UTR of cDNA expression vectors. If introns are included, they should be located in the 5′ UTR of the expression vector. Aberrant splicing between the splice donor site in the 5′ UTR and the cryptic splice acceptor site in the downstream cDNA is much less likely, because the splicing apparatus requires not only the splice acceptor site, but also the adjacent consensus sequence, including the branch point, for the splicing reaction to proceed.

The selection of appropriate introns is important for efficient RNA processing and to eliminate the utilization of the cryptic splice site in the coding region. Introns with splice sites and branch points that closely match the established consensus sequences are spliced more efficiently and accurately than ones that do not. Several introns have been used widely in mammalian expression vectors, including the second intron of the rabbit β-globin gene (O’Hare et al., 1981), and intron A of CMV (Hartikka et al., 1996). Some expression vectors include a hybrid intron, e.g., the 5′ portion of an adenovirus sequence and the 3′ portion of an immunoglobulin sequence (Choi et al., 1991).

TRANSCRIPTIONAL TERMINATION SEQUENCES

Most mature mRNAs have a post-transcriptionally added poly(A) tract at their 3′ end (Wahle and Ruegsegger, 1999). Usually preceding the poly (A) addition site is a sequence transcribed from the sequence AATAAA on the DNA. This sequence, the so-called poly (A) signal, is the most conserved recognition element in eukaryotes. This sequence motif directs the cleavage of primary transcripts approximately 20 base pairs downstream. The cleavage process also requires another, less conserved, normally G/U-rich recognition sequence that is located downstream of the poly (A) signal (Zhao et al., 1999). This sequence, in collaboration with the poly(A) signal, leads to the endonucleolytic attack. The poly (A) polymerase cleaves the transcripts after the U residue and adds 50–250 adenylate residues. Following poly (A) addition, the introns are cleaved and the mature mRNA is transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. This adenylation is believed to increase mRNA stability and is the convenient target for oligo (dT) primers in mRNA purification. Some poly (A) sites are promiscuous, which leads to a partial read-through and the production of mRNAs with different 3′ terminal ends. Therefore, in expression plasmid vectors it is important to include an effective poly (A) signal at the 3′ side of the cloning site. Poly (A) signals derived from the rabbit β-globin gen...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Color plates

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1: Basic components of gene expression plasmids

- 2: Inducible gene expression strategies in gene therapy

- 3: Modulation of gene expression by antisense oligonucleotides

- 4: Ribozymes as therapeutic agents and genetic tools

- 5: Peptide nucleic acids (PNA) binding-mediated target gene transcription

- 6: Aptamers for controlling gene expression

- 7: Enzymes acting on DNA breaks and its relevance in nucleic acid-based therapy

- 8: Compaction and condensation of DNA

- 9: Structure, dispersion stability and dynamics of DNA and polycation complexes

- 10: Structure and structure-activity correlations of cationic lipid/DNA complexes: supramolecular assembly and gene delivery

- 11: Cellular uptake, metabolic stability and nuclear translocation of nucleic acids

- 12: Nucleocytoplasmic trafficking

- 13: Optimizing RNA export for transgene expression

- 14: Naked plasmid DNA delivery of a therapeutic protein

- 15: Cationic lipid-based gene delivery

- 16: Peptide-based gene delivery systems

- 17: Cationic and non-condensing polymer-based gene delivery

- 18: Device-mediated gene delivery

- 19: Basic pharmacokinetics of oligonucleotides and genes

- 20: Interstitial transport of macromolecules: implication for nucleic acid delivery in solid tumors

- 21: Hepatic delivery of nucleic acids using hydrodynamics-based procedure

- 22: Role of CpG motifs in immunostimulation and gene expression

- 23: Local cardiovascular gene therapy

- 24 Gene therapy for cardiovascular disease

- 25: Gene therapy for the prevention of autoimmune diabetes