- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Afghanistan - A New History

About this book

Sir Martin Ewans, former Head of the British Chancery in Kabul, puts into an historical and contemporary context the series of tragic events that have impinged on Afghanistan in the past fifty years. The book examines the roots of these developments in Afghanistan's earlier history and external relationships, as well as their contemporary relevance

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Afghanistan - A New History by Sir Martin Ewans,Martin Ewans,Patrick Weber,Robyn Carr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Early History

For a country as closed and remote as Afghanistan, a great deal of archaeological research has been carried out over the years, although relatively little of it has covered the country’s prehistory. However enough has been found to show that the region was widely inhabited during the Palaeolithic and Neolithic eras. Evidence also exists of the practice of agriculture and pastoralism some 10,000 years ago. By the sixth millennium BC, lapis lazuli from Badakhshan was being exported to India, while excavations in Sistan and Afghan Turkestan have revealed evidence of a culture allied to that of the Indus civilisation of that time. By the second millennium, lapis lazuli1 from Afghanistan was in use in the Aegean area, where it has been found in one of the Shaft Graves at Mycenae, while tin, also possibly from Afghanistan, was being carried in a ship which was wrecked at Uluburun, off the Turkish coast, in 1336 BC. From very early times, therefore, the region’s commercial links stretched both to the east and to the west.

As is clear from the diversity of the population, as well as from the archaeological and historical evidence, Afghanistan has also over its long history been a ‘highway of conquest’ between west, central and southern Asia. The country has been incorporated into a series of empires, and successions of migrations and invasions have passed into and through it. One of the main migrations was that of the Indo-Aryan peoples, who spent some time on the Iranian Plateau and in Bactria, before going on to conquer and displace the pre-Aryan peoples of South Asia. It was not until the sixth century BC, however, that the region began to appear in recorded history, as the Achaemenid monarch, Cyrus the Great, extended his empire as far east as the River Indus. His successor, Darius the Great, created various satrapies in the area, among them Aria (Herat), Drangiana (Sistan), Bactria (Afghan Turkestan), Margiana (Merv), Chorasmia (Khiva), Sogdiana (Transoxania), Arachosia (Ghazni and Kandahar) and Gandhara (the Peshawar valley). The Achaemenids appear to have embraced Zoroastrianism, and tradition has it, somewhat uncertainly, that the renowned sage Zoroaster was born and lived in Bactria, and that he died in Bactra (Balkh) around 522 BC. The establishment of the eastern Achaemenid empire involved hard fighting and Persian rule was only maintained with difficulty. Greek colonists were brought in to help consolidate it, but by the fourth century BC, the satrapies to the south and east of the Hindu Kush seem to have regained their independence.

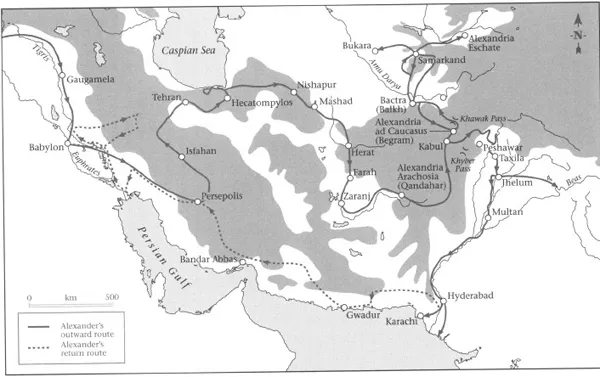

Map 4 Alexander’s Route to India

During the latter half of the fourth century, Achaemenid rule gave way to Greek, as Alexander of Macedon, having defeated Darius III in 331 BC at the Battle of Gaugamela, embarked on his epic march to the east. He subdued Persia, and then in 330 entered Afghanistan. As he advanced, he founded cities to protect his conquests, starting with Alexandria Ariana near what is now Herat. He then turned south to the Sistan and eastwards to the Kandahar area, where he founded Alexandria Arachosia. By the spring of 329 BC he had founded yet another city, Alexandria-ad-Caucasum, in the Kohistan valley north of Kabul. He then struck up the Panjshir Valley and north over the Hindu Kush, where his troops suffered severely from frostbite and snow blindness. He seized Bactria and crossed the Amu Darya, where the unfortunate satrap, Bassus, was delivered to him, tortured and executed. He then went on to take Marcanda (Samarkand), and built his remotest city, Alexandria-Eschate, ‘Alexandria-at-the-End-of-the-World’, on the Sri Darya. Hard fighting followed with the local nomadic tribes until the summer of 327 BC, when, after founding more cities, he retired over the mountains. Before doing so he married a Bactrian princess, Roxane, probably as a dynastic expedient and not, as the romantically inclined would have it, a love match.

Alexander then marched down to India, sending the bulk of his forces and equipment along the Kabul River, while he himself marched with a smaller force up the Kunar Valley and eastwards into Bajaur and Swat. The combined army then crossed the Indus and in 326 BC defeated the local king, Poros, at the battle of Jhelum. By that time, however, his troops had had enough of the unknown and, when he proposed going on beyond the Beas, they mutinied and compelled him to retreat. He built a fleet and sailed down the Indus, and then withdrew partly by sea and partly through the Makran, where his troops suffered severely from shortages of food and water. He died in 323, soon after arriving back in Babylon.

The empire that Alexander established quickly broke up and, in the Punjab, gave way to the Mauryan dynasty under Chandragupta. At the end of the fourth century, Alexander’s successor in the East, Seleucus Nikator, suffered a severe defeat at the hands of Chandragupta and was forced to cede to him most of the land to the south of the Hindu Kush. However friendly relations developed between the two kingdoms, a treaty was negotiated and envoys were exchanged. From the middle of the third century BC, under the great Mauryan king, Asoka, Buddhism began to flourish in both India and Afghanistan. Edicts of Asoka, carved on pillars or rocks, have been found in both countries, and bear witness to the strength of his Buddhist convictions. Bactria, however, remained a Seleucid satrapy and was settled by further Greek colonists, and then, also in the middle of the third century, became an independent Graeco-Bactrian kingdom. Over many years, from the 1920s onwards, French archaeologists searched for a Graeco-Bactrian city in northern Afghanistan. In 1963 they eventually found one, at Ai Khanum2 in Taloqan Province, at the confluence of the Kokcha River and the upper reaches of the Amu Darya. Excavations there revealed the remains of a wealthy and sophisticated Hellenistic city, with a citadel, palace, temples and gymnasium. It appears to have been sacked and burnt at the end of the second century BC, probably by nomad invaders. Around the same time as Bactria broke away from Seleucid rule, the Parthians, originally a Scythian nomad people, supplanted the Seleucids in Persia and established an independent kingdom that was to withstand the Roman Empire and last until 226 AD.

Soon after Asoka’s death in 232 BC, the Mauryan Empire declined and in about 184 the Bactrian Greeks, having conquered Aria and Arachosia, captured Gandhara and penetrated as far as the Mauryan capital at Patna. Under Menander, who ruled between 155 and 130, they extended and stabilised their rule in India, with their capital at Shakala (now Sialkot). In India, the Bactrians came under Buddhist influence, although in Bactria itself, Buddhism had not yet penetrated, and the region remained predominantly Persian in culture, although still under Greek rule.

However new actors were now appearing on the scene, with the onset of what has been called ‘the great migration of peoples’ out of central Asia. Speculation has it that this may have been sparked off by a combination of climatic change, which may have caused the pasture lands of central Asia to dry up, and the construction of the Great Wall of China by the Chinese Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi. Unable to move their flocks eastwards, nomad peoples began to move towards the west. The first of the migrants were the Yüeh-chih, who seem to have been driven from Central Asia by the Hsiung-Nu, later known in the West as the Huns. A majority of the Yüeh-chih began by moving towards Lake Balkhash, in turn driving before them the inhabitants of the region, a Scythian people known as the Sakas. The latter overran Bactria and moved against Parthia, but encountered resistance from the Parthians and detoured southwards to Sistan (Sakastan). From there they moved eastwards into Sind and northwards to Gandhara and the Indus valley, where they established themselves early in the first century BC. They did not, however, for long remain independent of the Parthians, who in the early first century AD briefly extended their empire as far east as the Punjab. Meanwhile the Yüeh-chih themselves moved westwards and southwards. Some of them attacked the Parthians, while others crossed the Amu Darya in about 130 BC and conquered Bactria. In around 75 AD they crossed the Hindu Kush under Kujula Kadphises, the leader of one of their five tribal groups, the Gui-shang. They then invaded India, stormed Taxila, the main Parthian city, and defeated the Sakas and their Parthian overlords.

The Gui-shang, or Kushans, as the Yüeh-chih were to be known, proceeded to extend their rule over the whole of the Punjab and the Ganges valley as far as Vatanasi. To the west, they conquered Aria, Sakastan and Arachosia, while to the north, their territories stretched to the Caspian and Aral Seas. Their greatest king, Kanishka, who probably ruled during the second century AD, established a capital at Mathura and a northern capital near Peshawar. A summer capital was also founded at Kapisa in the Kohistan valley. Trading links with the Middle East were revived, as was the Silk Route to China, and the Kushans conducted a thriving trade with Rome and the Han Dynasty. Remarkably, the kingdom that these Central Asian nomads proceeded to establish was notable for both its religious and its artistic achievements. At an earlier stage, they may have been fire worshippers in the Zoroastrian tradition, and a fire temple dedicated to Kanishka has been unearthed at Surkh Kotal, near Pul-i-Khumri, just north of the Hindu Kush. However Buddhism again flourished and, in its Mahayana form, spread through Afghanistan and along the Silk Route to Central Asia and China. Hellenism seems also to have retained its cultural presence in the area and was reinforced through contacts with Alexandria, so that a combination of Greek and Buddhist influences produced the Indo-Hellenic style of sculpture known as Gandharan, many examples of which, often of great beauty and delicacy, have been found on Afghan sites. Excavations at Kapisa have yielded a magnificent array of some two thousand priceless art treasures, originating from as far afield as China, India, Alexandria and Rome, while what was clearly a complex of flourishing monasteries at Hadda, near Jalalabad, has produced thousands of statues and images in the Gandharan style. Most spectacularly, two huge images of the Buddha have survived at Bamian, carved into the cliff face at the margin of the valley. These probably date from the third and fifth centuries AD, and the number of monastic cells carved into the cliffs around them show that this was a major Buddhist centre. Hsüan Tsang3, who visited Bamian in the course of his journey in the seventh century, found ‘several dozen monasteries and several thousand monks’ still in the area.

The Kushans ruled for some five centuries, yielding territory in the mid third century AD to the Persian Sassanid dynasty, which had supplanted the Parthians, but surviving in north-west India until the invasion of the Ephthalites, the White Huns, during the fifth century. The origins of the Ephthalites remain shrouded in mystery. They may have been subjects of the Avars of Mongolia, who broke away and migrated through Turkestan to Bactria, where they drove out the Kushans, crossed the Hindu Kush and occupied north-west India. Unlike earlier invaders, who had accommodated themselves to the pre-existing civilisations, the Ephthalites sacked the cities, slaughtered the inhabitants and dispersed the religious communities. They ruled for about a century, but had to fight off the Sassanids and in 568 succumbed to a joint onslaught by the latter and the Turkish peoples of Central Asia.

A new and more enduring era then started to dawn in Afghanistan, that of Islam. In 637 and 642, the Muslim Arabs defeated the Sassanids, who were exhausted by internal dissension, and in 650 or thereabouts they occupied Herat and Balkh. Beyond that, however, the Arab advance was slow and halting, and was hindered by a succession of conflicts within the Ummayid and Abbasid Caliphates. The Arabs advanced through Sistan and conquered Sind early in the eighth century. Elsewhere, however, their incursions were no more than temporary, and it was not until the rise of the Saffarid dynasty in the ninth century that the frontiers of Islam effectively reached Ghazni and Kabul. Even then, a Hindu dynasty, the Hindushahis, held Gandhara and the eastern borders. From the tenth century onwards, as Persian language and culture continued to spread into Afghanistan, the focus of regional power shifted to Ghazni, where a Turkish dynasty, who started by ruling the town for the Samanid dynasty of Bokhara, proceeded to create an empire in their own right. The greatest of the Ghnaznavids was Mahmud, who ruled between 998 and 1030. He expelled the Hindus from Ghandara, made no fewer than seventeen raids into India and succeeded in conquering territory stretching from the Caspian Sea to beyond Vatanasi. Bokhara and Samarkand also came under his rule. He encouraged mass conversions to Islam, in India as well as Afghanistan, looted Hindu temples and carried off immense booty, earning for himself, depending on the viewpoint of the observer, the titles of ‘Image-breaker’ or ‘Scourge of India’. In Ghazni, he carried out a prestigious building programme and his court became a centre for scholars and poets, including the renowned Persian poet, Firdausi. Ghazni itself was subsequently destroyed several times over, but the remains of three magnificent Ghaznavid palaces are still to be seen at Lashkari Bazar, at the confluence of the Helmand and Argandab Rivers. After Mahmud’s death, Ghaznavid power was weakened by a Seljuk invasion from Persia, and was supplanted by that of the Ghorids, who sacked Ghazni in 1150 and established their capital in Herat. Coming from central Afghanistan, the Ghorids, who were also of Turkish stock, then invaded India, where they captured Lahore and Delhi. Their short reign was to go down in history for the construction of the Qutb Minar outside Delhi, the Masjid-i-Juma (Friday Mosque) in Herat and the remote Minaret of Djam in the wilds of the Hezarajat, which was only rediscovered in 1943. In 1215, the Ghorids were in turn conquered by the Khwarizm Shahs, with their capital at Khiva.

There then occurred one of the most cataclysmic events of Afghan history, the invasion of the Mongol hordes under their chieftain Genghis Khan. The latter was a brilliant military commander and administrator, who founded an empire that eventually stretched from Hungary to the China Sea and from northern Siberia to the Persian Gulf and the Indian sub-continent. The origins of his followers are still a matter of dispute, the most likely theory being that they were descendants of the Hsiung-Nu. Genghis Khan’s achievement was to weld them into a formidable fighting force, distinguished by its superb cavalry, which was capable of highly disciplined manoeuvre and sustained advance at great speed, even over near-impossible terrain. Genghis Khan himself started life as an abandoned orphan, but managed after many vicissitudes to attract support to the point where, in 1206, he was proclaimed emperor of a Mongol confederation, probably some two million strong. In 1218, out of the blue, he and his followers descended on Turkestan, defeated the Khwarizm Shahs and took Bokhara and Samarkand, which they comprehensively sacked. In 1221 they took Balkh, razed it to the ground and massacred its inhabitants. When the Taoist seer and healer, Ch’ang Ch’un, who had been summoned from China to Genghis’ court in Afghanistan, arrived at the city a short while after the massacre, he found4 that the citizens had been ‘removed’, but ‘we could still hear dogs barking in its streets’. The Mongols treated Herat leniently when it first surrendered to them, but when it rebelled six months later, it was speedily retaken and all its inhabitants were executed, the process taking seven days to complete. Bamian was also razed and its population slaughtered, leaving today only the ruins of two hilltop fortresses, the Shahr-i-Zohak (Red City) and the aptly named Shahr-i-Gholgola (City of Sighs) as evidence of the calamity. Ghazni then suffered the same fate, as did Peshawar, but Genghis Khan did not advance beyond the Punjab, probably nervous of the effect on his army of the heat of the Indian plains. The overall outcome of the Mongol invasion was widespread depopulation, devastation and economic ruin. When the Moroccan traveller, Ibn Batuta, passed through Afghanistan a century later, he found5 Balkh in ruins and uninhabited, Kabul no more than a village and Ghazni devastated. He reports Genghis Khan as having torn down the mosque at Balkh, ‘one of the most beautiful in the world’, because he believed that treasure had been hidden beneath one of its columns.

Following Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, his sons and grandsons ruled his empire, most of Afghanistan coming under his second son, Jaghatai, whose descendants established themselves in Kabul and Ghazni. Herat alone retained a degree of autonomy under a Tajik dynasty, the Karts. From 1364 onwards, the western part of the khanate came under the control of Tamerlane (a corruption of Timur-i-Leng – Timur the Lame), a Turko-Mongol who claimed, apparently falsely, descent from Genghis himself. Tamerlane began by expelling the Mongols from Transoxania and around 1370 proclaimed himself emperor at Balkh. He too went on to create an extensive empire, which included Afghanistan and northern India, and in 1398 he took Delhi and slaughtered its inhabitants. Among his unpleasant habits was that of stacking into pyramids the heads of those he had massacred or incorporating them into walls. In the Sistan, he destroyed the irrigation works that stemmed from the Helmand River, with the result that what had been a prosperous and well-inhabited region was turned into a desert waste. The weathered remains of substantial towns and fortresses even today provide clear evidence of the scale of the destruction, from which Sistan never recovered. However, unlike Genghis Khan, Tamerlane was, despite his barbaric propensities, a man of culture, and he transformed the Timurid capital, Samarkand, into an intellectual and artistic centre. His tomb there is one of the glories of Islamic architecture. His empire began to disintegrate after his death in 1405, but his dynasty, the Timurids, continued to rule in Turkestan and Persia until the early sixteenth century. Under his son, Shah Rukh, Herat became the centre of what has been called the Timurid Renaissance, with a thriving culture notable for its architecture, its literary and musical achievements, and its calligraphy and miniature painting. Shah Rukh’s formidable wife, Gohar Shad, was responsible for the building of the Musalla, the complex of mosque, college and mausoleum which, with its several minarets, dominated the Herat skyline over many centuries. The bulk of it was razed at the time of the Panjdeh crisis in 1885, to create a clear field of fire for the defenders of the city, in the event, thought to be imminent, of a Russian attack from the north. Of the minarets which were left, Robert Byron says6, in his encomium of Timurid architecture,

Their beauty is more than scenic, depending on light and landscape. On closer view, every tile, every flower, every petal of mosaic contributes its genius to the whole. Even in ruin, such architecture tells of a golden age…. The few travellers who have visited Samarkhand and Bokhara as well as the shrine of the Imam Riza [in Meshed], say that nothing in these towns can equal the last. If they are right, the Mosque of Gohar Shad must be the greatest surviving monument of the period, while the ruins of Herat show that there was once a greater.

The Timurid Renaissance lasted little more than a century. Following Shah Rukh’s death in 1447, ten successive rulers held Herat over a period of a mere twelve years, but it was then taken by another Timurid, Husain-i-Baiqara, who gave it a further forty years of peace and a renewed cultural flowering. The miniature painter Bihzad, the poet Abdurrahman Jami and the historian Mishkwand all embellished his court. Then, during the sixteenth century, two new dynasties began to impinge on Afghanistan. In Persia, the Safavids presided over a national renaissance and survived until well into the eighteenth century, despite conflicts with the Ottoman Turks and the Usbeks, who had moved south into the region around 1500. Also at the turn of the sixteenth century, a descendant of both Tamerlane and Genghis Khan, Mohammed Zahir-ud-din, better known as Babur, a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Maps

- Introduction: The Land and the People

- 1 Early History

- 2 The Emergence of the Afghan Kingdom

- 3 The Rise of Dost Mohammed

- 4 The First Anglo-Afghan War

- 5 Dost Mohammed and Sher Ali

- 6 The Second Anglo-Afghan War

- 7 Abdur Rahman, The ‘Iron Amir’

- 8 Habibullah and the Politics of Neutrality

- 9 Amanullah and the Drive for Modernisation

- 10 The Rule of the Brothers

- 11 Daoud: The First Decade

- 12 King Zahir and Cautious Constitutionalism

- 13 The Return of Daoud and the Saur Revolution

- 14 Khalq Rule and Soviet Invasion

- 15 Occupation and Resistance

- 16 Humiliation and Withdrawal

- 17 Civil War

- 18 Enter the Taliban

- 19 The Taliban Regime

- 20 Oil, Drugs and International Terrorism

- 21 The Fall of the Taliban

- 22 The Future

- Appendix: The Durrani Dynasty

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index